Beyond Observation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUSINESS Reagan Asks Moscow to Work for Peace

ZO - M ANCHESTER HERALD. Saturday, Jan. 14, 1984 BUSINESS Elliott recalls years Debate by Democrats MHS hockey In courtand before becomes yelling match tourney-bound \ Business Check first to avoid 'moving shock’ ... page 3 page 4 ... page 11 In Brief If you’re among the 80 percent of shoppers for a new Some utilities, such as Florida Power 4 home, the odds are that a prime consideration you'll evaluate the energy integrity of a house. Other Snow now an associate overlook (until too late) is the compatibility of a new utilities, such as Pennsylvania Power 4 Light, have neighborhood. As a result, you will be hit by "m oving Your worked with local builders to create energy-efficient William Snow of Manchester was recently shock” when you discover the culture and costs of the housing developments. recognized as an associate by Positions Inc., a new location differ dramatically from what you have Money's New England-based network of eight executive • Check out the living habits of the present owners become accustomed to. search and placement offices. of a house if the utility bills appear suspiciously low. Another major consideration overlooked by the vast Worth Snow today; Manchester, Conn. The associate designation is awarded only after Winter underwear and not energy efficiency may be majority of home shoppers will be the energy an individual has demonstrated a high degree of Sylvia Porter the reason. sunny Tuesday Monday, Jan. 16, 1984 efficiency of a new house — and the adverse effects of professional competence within the organization. • Be sure not to overlook the efficiency of hot water an energy-inefficient home on your overall housing — See page 2 Single copy; 25<t Snow, a Boston University graduate, is heaters and refrigerators. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

HP0192 Lindsay Anderson

1 The copyright of this interview is vested in the BECTU History Project. Lindsay Anderson, film director, theatre producer, interviewer Norman Swallow, recorded on 18 April, 1991 SIDE 1 Norman Swallow: First of all, when and where were you born? Lindsay Anderson: I was born on April 17th, 1923 in Bangalore, South India in the military hospital, I think. My father was in the British army in India, the Queen Victoria's Own, the Royal Engineers. My mother was half Scottish, her mother was Scottish and her father was English. She was born in South Africa and had met my father in Scotland . He was Scottish, and his family lived in Stonehaven, which is south of Aberdeen, and that is where they met and got married. Not altogether happily I don t think. There was a first son who died, a second son, my brother, who is living, who was an airline pilot and also flew in the War, and myself was born in India. And my parents divorced, do you know I can't even remember quite when, probably 10 or 11. I never knew my father terribly well, he served in India and most of time, I was brought up in England. I went to a respectable English preparatory school in West Worthing, St Ronan's, and I went to Cheltenham College. Not through any family connections, but my brother went to Cheltenham. And he went into the army, and then transferred into the airforce. I wasnt in the least military. I went up to Oxford for a year during the war and then went into the army. -

Book Reviews – February 2014

Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies Issue 26 February 2014 Book Reviews – February 2014 Table of Contents Watching the World: Screening Documentary and Audiences By Thomas Austin A Journey through Documentary Film By Luke Dormehl American Documentary Film: Projecting the Nation By Jeffrey Geiger A Review by Douglas C. MacLeod Jr. ............................................................. 6 Performance in the Cinema of Hal Hartley By Steven Rawle Hal Hartley By Mark L. Berrettini A review by Jennifer O'Meara..................................................................... 14 Hunting the Dark Knight: Twenty-First Century Batman By Will Brooker The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader Edited by Christoph Lindner A Review by Matthew Freeman .................................................................. 21 Film and Female Consciousness: Irigaray, Cinema and Thinking Women By Lucy Bolton Civilized Violence: Subjectivity, Gender and Popular Cinema. By David Hansen-Miller A Review by Katherine Whitehurst.............................................................. 28 1 Book Reviews New Takes in Film-Philosophy Edited by Havi Carel and Greg Tuck Deleuze and Cinema: The Film Concepts By Felicity Colman Deleuze and World Cinemas By David Martin-Jones A Review by Sergey Toymentsev ............................................................... 35 The British Film Institute, the Government and Film Culture, 1933-2000 edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith and Christophe Dupin J. Edgar Hoover Goes to the Movies: The FBI -

File Stardom in the Following Decade

Margaret Rutherford, Alastair Sim, eccentricity and the British character actor WILSON, Chris Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17393/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17393/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus 2S>22 Sheffield S1 1WB 101 826 201 6 Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour REFERENCE Margaret Rutherford, Alastair Sim, Eccentricity and the British Character Actor by Chris Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2005 I should like to dedicate this thesis to my mother who died peacefully on July 1st, 2005. She loved the work of both actors, and I like to think she would have approved. Abstract The thesis is in the form of four sections, with an introduction and conclusion. The text should be used in conjunction with the annotated filmography. The introduction includes my initial impressions of Margaret Rutherford and Alastair Sim's work, and its significance for British cinema as a whole. -

Full Members of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (Updated 22 March 2011)

Full Members of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (updated 22 March 2011) Roberta Aarons Yavar Abbas Allison Abbate Jeff Abberley Peter Abbey Paul Abbott Steve Abbott Bassem Abdallah Brian Abel David Abraham Eric Abraham Georgina Abrahams Bruce Abrahams Joe Abrams Jenny Abramsky Farah Abushwesha Huda Abuzeid Juliet Ace Roy Ackerman Steve Ackhurst Joss Ackland Barry Ackroyd Ken Adam Richard Adams Ross Adams Mark Adams Gordon Adams Benetta Adamson Madeline Addy Henry Adeane David Adler Melanie Adorian Tony Ageh Phil Agland Joss Agnew Steen Agro Jenny Agutter Sanjiv Ahuja Pippa Ailion Lucy Ainsworth-Taylor Christopher Aird Dawn Airey Tony Aitken Eleanor Aitken Mike Aiton Abby Ajayi Jovan Ajder Niyi Akeju Zara Akester Colin Akester Nassreen Akhtar Odunayo Akinwolere John Akomfrah Basi Akpabio Timothy Alban Francesco Alberico Philip Alberstat Simon Albury Julian Alcantara Jane Aldous Nuala Alen-Buckley Tom Alexander John Alexander Eva Alexander Darrell Alexander Jon Alexander Arnna Alexander Adam Alexander Rob Alexander Michael Algar Rosie Alison Luke Alkin Foz Allan Shane Allen Joe Allen Ged Allen Tony Allen Kenton Allen James Allen Katherine Allen James Allen Belinda Allen Angela Allen Peter Allen Richard Allen-Turner Lynn Alleway Rebecca Alleway Anthony Alleyne Waheed Alli Christopher Allies Ron Allison Daisy Allsop Christine Allsopp Pedro Almodovar Agustin Almodovar David Alpin Tess Alps Caroline Alterskye-Knight John Altman Richard Alwyn Vanessa Amberleigh Chris Ambler David Ambrose Arash Amel Paul Amer Asitha Ameresekere -

I I I I I Il Llll I I 111111

. --<· �� _;, -· _...,. .,... ·-' [.. '\. ..:i ;, � Richard Lowell MacDonald Thesis Title: Film Appreciation and the Postwar Film Society Movement Goldsmiths, University of London PhD in Media and Communications _ 1 GOLDSMITHS IIIIII I I II I Ill llllllll II II 111111111111111 8703241519 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I began this research I did not know that it would lead me towards the film societies. In fact I'm not sure that I had much sense of their existence. My interest was in exploring the internationalist sentiments of art cinema audiences. Flicking through an old copy of Films and Filming, I read about a film society in Ruislip which showed Bufiuel and Kurosawa films on l6mm projectors in my old primary school, and this captured my imagination. I owe thanks to many people for generously sharing their memories and experiences of being involved in film societies from the 1940s to the present, for passing on programmes and magazines from their personal collections and for extending me their hospitality. These conversations deepened my understanding of this movement immeasurably. Thank you to Sylvia and Peter Bradford, Sid Brooks, Gwen Bryanston, Anne Burrows, Percy Childs, James Clark, Brian Clay, Michael Essex-Lopresti, Denis Forman, Leslie Hardcastle, Alan Howden, David Meeker, John and Doris Minchinton, Gwen Molloy, Victor Perkins, Rommi Przibram, John Salisbury, Mansel Stimpson, Mike Taylor, John Turner, Jean Young and Dave Watterson. I am also grateful to Melanie Selfe who generously shared her ideas and writing on film societies. It is also true to say that I did not know much about teaching, and teaching film in particular, when I started this project. -

Calendar 2019 -20

CALENDAR 2019 -20 November 2019 CONTENTS OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY ………………………………………………………………………….6 UNIVERSITY DIARY ....................................................................................................................................... 7 THE FACULTIES ......................................................................................................................................... 8 STUDENTS’ UNION AND KEELE POSTGRADUATE ASSOCIATION OFFICERS ........................ 9 THE COUNCIL 2019 - 2020 ...................................................................................................................... 10 THE SENATE 2019-2020 .......................................................................................................................... 12 GENERAL INFORMATION ......................................................................................................................... 13 HONORARY DEGREES AWARDED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF KEELE........................................ 16 UNIVERSITY OF KEELE ACT, 1962 ....................................................................................................... 24 CHARTER ......................................................................................................................................................... 27 STATUTES ....................................................................................................................................................... 34 SECTION 1: DEFINITIONS .............................................................................................................. -

The State Funeral of Sir Winston Churchill

A Life Rewound Part Three Chapter Page 17 1965 Directs ITV’s five-hour (45 cameras) outside-broadcast: 137 The State Funeral of Sir Winston Churchill 18 1965 Documentary about the London Symphony Orchestra: 149 LSO - The Music Men 19 1965-69 Chairman of Society of Film and Television Arts. 156 Associated-Rediffusion loses its franchise. 13-part series: The Life and Times of Lord Mountbatten 20 1969 Appointed OBE. 180 Continues freelancing with other ITV companies. Outside-broadcast: Investiture of Prince Charles at Caernarvon Documentary: A Child of the Sixties 21 1970 Articles on the ‘Future of a 2nd ITV channel’. 187 Documentary on World War I anti-German hysteria: The First Casualty 22 1971-74 13- part history of Europe in the 20th Century for BBC-1: 194 The Mighty Continent 136 Chapter 17 1964 marked my fourth year planning – with my other hand – the programme with an unknown transmission date. In 1960, the Queen had officially given her consent for Sir Winston Churchill to have a State Funeral, and the BBC and the Independent Television Authority were officially informed that detailed plans for the great event were about to be made available to the broadcasters. It had been decided that regardless of the day of the week of Churchill’s death, the funeral would take place on a Saturday. Rediffusion was the London weekday contractor, with ATV taking over at weekends, but the ITA instructed Rediffusion to handle this complicated outside broadcast. My boss, John McMillan, the Controller of Programmes, had asked me to take charge of this project as producer and controlling director on behalf of the whole ITV network. -

Denis-Forman.Pdf

BECTU History Project - Interview No. 85 [Copyright BECTU] Transcription Date: (Digital: 2012-10-02) Interview Date: 1989-05-11 Interviewers: John Taylor, Stephen Peet Interviewee: Sir Denis Forman Tape 1, Side 1 Denis Forman: I was born in the lowlands of Scotland in Dumfriesshire in the Parish which had the remarkable name of Kirkpatrick Joxta near the Village of Beattock. The house was a biggish country scottish house called Craigielands, and I grew up there in a very remote kind of society enclosed in a family circle. I was taught by my Grandmother, my Father and Mother. I did not go to school until I was fifteen and we had eight children in the nursery and in the schoolroom, I suppose four or five servants in the house and a small Scottish estate. It was a closed community and a very strange life compared with what we have today. Taylor/Peet: Was your father the Minister there? Denis Forman: Off and on throughout his life he was a Minister but never really seriously, he went into Holy Orders after he left Cambridge. Just to go back a little he proposed marriage to my mother when she was fourteen and he was eighteen. Her father thought this was a little premature, so he sent him off to America, San Francisco for some years and when he came back he decided he would go into Holy Orders, went to Cambridge by this time he was about twenty-seven, then they were allowed to get married. Denis Forman: I think it was nearly ten years after they had been engaged and he went to Loretto School as a Chaplain. -

Why Are Comedy Films So Critically Underrated?

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2012 Why are Comedy Films so Critically Underrated? Michael Arell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Arell, Michael, "Why are Comedy Films so Critically Underrated?" (2012). Honors College. 93. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/93 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHY ARE COMEDY FILMS SO CRITICALLY UNDERRATED? by Michael Arell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Bachelor of Music in Education) The Honors College University of Maine May 2012 Advisory Committee: Michael Grillo, Associate Professor of History of Art, Advisor Ludlow Hallman, Professor of Music Annette F. Nelligan, Ed.D., Lecturer, Counselor Education Tina Passman, Associate Professor of Classical Languages and Literature Stephen Wicks, Adjunct Faculty in English © 2012 Michael Arell All Rights Reserved Abstract This study explores the lack of critical and scholarly attention given to the film genre of comedy. Included as part of the study are both existing and original theories of the elements of film comedy. An extensive look into the development of film comedy traces the role of comedy in a socio-cultural and historical manner and identifies the major comic themes and conventions that continue to influence film comedy. -

Table of Membership Figures For

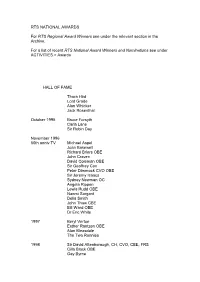

RTS NATIONAL AWARDS For RTS Regional Award Winners see under the relevant section in the Archive. For a list of recent RTS National Award Winners and Nominations see under ACTIVITIES > Awards HALL OF FAME Thora Hird Lord Grade Alan Whicker Jack Rosenthal October 1995 Bruce Forsyth Carla Lane Sir Robin Day November 1996 60th anniv TV Michael Aspel Joan Bakewell Richard Briers OBE John Craven David Coleman OBE Sir Geoffrey Cox Peter Dimmock CVO OBE Sir Jeremy Isaacs Sydney Newman OC Angela Rippon Lewis Rudd OBE Naomi Sargant Delia Smith John Thaw CBE Bill Ward OBE Dr Eric White 1997 Beryl Vertue Esther Rantzen OBE Alan Bleasdale The Two Ronnies 1998 Sir David Attenborough, CH, CVO, CBE, FRS Cilla Black OBE Gay Byrne David Croft OBE Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly Verity Lambert James Morris 1999 Sir Alistair Burnet Yvonne Littlewood MBE Denis Norden CBE June Whitfield CBE 2000 Harry Carpenter OBE William G Stewart Brian Tesler CBE Andrea Wonfor In the Regions 1998 Ireland Gay Byrne Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly James Morris 1999 Wales Vincent Kane OBE Caryl Parry Jones Nicola Heywood Thomas Rolf Harris AM OBE Sir Harry Secombe CBE Howard Stringer 2 THE SOCIETY'S PREMIUM AWARDS The Cossor Premium 1946 Dr W. Sommer 'The Human Eye and the Electric Cell' 1948 W.I. Flach and N.H. Bentley 'A TV Receiver for the Home Constructor' 1949 P. Bax 'Scenery Design in Television' 1950 Emlyn Jones 'The Mullard BC.2. Receiver' 1951 W. Lloyd 1954 H.A. Fairhurst The Electronic Engineering Premium 1946 S.Rodda 'Space Charge and Electron Deflections in Beam Tetrode Theory' 1948 Dr D.