Nancy Sandars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AVAS Newsletter 2016

AVON VALLEY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER December 2016 Editorial This year is a swan song for me as this twelfth edition of the Newsletter will be my last one. I feel that I have had a good innings and that it is time to pass baton on to someone who will bring a fresh vision to the task. As I stated last year there is a distinct move away from excavation work in archaeology and this trend is continuing, but our work with resistivity techniques to do non-invasive searches, supplemented by the use of Magnetometry, using some equipment borrowed from Bournemouth University has proved a revelation. For those who wish to know more and see some of the results, then attendance at our Members Evening in January is a must! We really are discovering more and disturb less! My last edition of our newsletter, like a number of previous copies is taking in some practical archaeological topics and attempting to stimulate members to seek out even more interesting places based upon the travels of a number of our members. Our blog site continues to flourishing. So once again, our thanks go to Mike Gill for his continuing work in keeping the news of activities and plans of AVAS available to our members and the general public at large. So let us all support them with any useful news or other input that we, as members, might come up with. N.B. The address on the web for our blogsite is at the bottom of this page. I hope that this edition of the Newsletter will be both stimulating and entertaining and wish you all great year of archaeology in 2017. -

Archaeology Book Collection 2013

Archaeology Book Collection 2013 The archaeology book collection is held on the upper floor of the Student Research Room (2M.25) and is arranged in alphabetical order. The journals in this collection are at the end of the document identified with the ‘author’ as ‘ZJ’. Use computer keys CTRL + F to search for a title/author. Abulafia, D. (2003). The Mediterranean in history. London, Thames & Hudson. Adkins, L. and R. Adkins (1989). Archaeological illustration. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Adkins, L. and R. A. Adkins (1982). A thesaurus of British archaeology. Newton Abbot, David & Charles. Adkins, R., et al. (2008). The handbook of British archaeology. London, Constable. Alcock, L. (1963). Celtic Archaeology and Art, University of Wales Press. Alcock, L. (1971). Arthur's Britain : history and archaeology, AD 367-634. London, Allen Lane. Alcock, L. (1973). Arthur's Britain: History and Archaeology AD 367-634. Harmondsworth, Penguin. Aldred, C. (1972). Akhenaten: Pharaoh of Egypt. London, Abacus; Sphere Books. Alimen, H. and A. H. Brodrick (1957). The prehistory of Africa. London, Hutchinson. Allan, J. P. (1984). Medieval and Post-Medieval Finds from Exeter 1971-1980. Exeter, Exeter City Council and the University of Exeter. Allen, D. F. (1980). The Coins of the Ancient Celts. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press. Allibone, T. E. and S. Royal (1970). The impact of the natural sciences on archaeology. A joint symposium of the Royal Society and the British Academy. Organized by a committee under the chairmanship of T. E. Allibone, F.R.S, London: published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. Alves, F. and E. -

Contacts: Crete, Egypt, and the Near East Circa 2000 B.C

Malcolm H. Wiener major Akkadian site at Tell Leilan and many of its neighboring sites were abandoned ca. 2200 B.C.7 Many other Syrian sites were abandoned early in Early Bronze (EB) IVB, with the final wave of destruction and aban- donment coming at the end of EB IVB, Contacts: Crete, Egypt, about the end of the third millennium B.c. 8 In Canaan there was a precipitous decline in the number of inhabited sites in EB III— and the Near East circa IVB,9 including a hiatus posited at Ugarit. In Cyprus, the Philia phase of the Early 2000 B.C. Bronze Age, "characterised by a uniformity of material culture indicating close connec- tions between different parts of the island"10 and linked to a broader eastern Mediterra- This essay examines the interaction between nean interaction sphere, broke down, per- Minoan Crete, Egypt, the Levant, and Ana- haps because of a general collapse of tolia in the twenty-first and twentieth cen- overseas systems and a reduced demand for turies B.c. and briefly thereafter.' Cypriot copper." With respect to Egypt, Of course contacts began much earlier. Donald Redford states that "[t]he incidence The appearance en masse of pottery of Ana- of famine increases in the late 6th Dynasty tolian derivation in Crete at the beginning and early First Intermediate Period, and a of Early Minoan (EM) I, around 3000 B.C.,2 reduction in rainfall and the annual flooding together with some evidence of destructions of the Nile seems to have afflicted northeast and the occupation of refuge sites at the time, Africa with progressive desiccation as the suggests the arrival of settlers from Anatolia. -

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present

Parker Pearson, M 2013 Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present. Archaeology International, No. 16 (2012-2013): 72-83, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ai.1601 ARTICLE Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present Mike Parker Pearson* Over the years archaeologists connected with the Institute of Archaeology and UCL have made substantial contributions to the study of Stonehenge, the most enigmatic of all the prehistoric stone circles in Britain. Two of the early researchers were Petrie and Childe. More recently, colleagues in UCL’s Anthropology department – Barbara Bender and Chris Tilley – have also studied and written about the monument in its landscape. Mike Parker Pearson, who joined the Institute in 2012, has been leading a 10-year-long research programme on Stonehenge and, in this paper, he outlines the history and cur- rent state of research. Petrie and Childe on Stonehenge William Flinders Petrie (Fig. 1) worked on Stonehenge between 1874 and 1880, publishing the first accurate plan of the famous stones as a young man yet to start his career in Egypt. His numbering system of the monument’s many sarsens and blue- stones is still used to this day, and his slim book, Stonehenge: Plans, Descriptions, and Theories, sets out theories and observations that were innovative and insightful. Denied the opportunity of excavating Stonehenge, Petrie had relatively little to go on in terms of excavated evidence – the previous dig- gings had yielded few prehistoric finds other than antler picks – but he suggested that four theories could be considered indi- vidually or in combination for explaining Stonehenge’s purpose: sepulchral, religious, astronomical and monumental. -

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-Linguistic Status : a Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-linguistic Status: A Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany by Ted Cicholi RN (Psych.), MA. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science School of Government 22 September 2004 Disclaimer Although every effort has been taken to ensure that all Hyperlinks to the Internet Web sites cited in this dissertation are correct at the time of writing, no responsibility can be taken for any changes to these URL addresses. This may change the format as being either underlined, or without underlining. Due to the fickle nature of the Internet at times, some addresses may not be found after the initial publication of an article. For instance, some confusion may arise when an article address changes from "front page", such as in newspaper sites, to an archive listing. This dissertation has employed the Australian English version of spelling but, where other works have been cited, the original spelling has been maintained. It should be borne in mind that there are a number of peculiarities found in United States English and Australian English, particular in the spelling of a number of words. Interestingly, not all errors or irregularities are corrected by software such as Word 'Spelling and Grammar Check' programme. Finally, it was not possible to insert all the accents found in other languages and some formatting irregularities were beyond the control of the author. Declaration This dissertation does not contain any material which has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any tertiary institution. -

The Fifteenth Mount Haemus Lecture

THE ORDER OF BARDS OVATES & DRUIDS MOUNT HAEMUS LECTURE FOR THE YEAR 2014 The Fifteenth Mount Haemus Lecture ‘Almost unmentionable in polite society’? Druidry and Archaeologists in the Later Twentieth Century by Dr Julia Farley Introduction Between 1950 and 1964, a major programme of archaeological excavations were carried out at Stonehenge, directed by archaeologists Richard Atkinson and Stuart Piggott. The excavations were not published in full until after Atkinson’s death (Cleal et al. 1995), but Atkinson penned a popular account of the site in 1956, entitled simply Stonehenge, which was aimed at “the ordinary visitor” (Atkinson 1956, xiv). The book was, in part, intended to dispel once and for all the popular notion that there was a direct connection between ancient Druids and Stonehenge. Atkinson went so far as to write that “Druids have so firm a hold upon the popular imagination, particularly in connection with Stonehenge, and have been the subject of so much ludicrous and unfounded speculation, that archaeologists in general have come to regard them as almost unmentionable in polite society.” (ibid., 91). This quote is notable for two reasons. Firstly, it highlights the often fraught relationships between archaeologists and Druidry in the mid-twentieth century and, secondly, it was soon to be revealed as demonstrably untrue. At the time that Atkinson was writing, the last major academic treatment of the ancient Druids was Thomas Kendrick’s The Druids, published in 1927. But a decade after the publication of Atkinson’s book, at a time of heightened tensions with modern Druid movements over rights and access to Stonehenge, two major academic monographs on ancient Druids were published (Piggott 1966, Chadwick 1966), as well as a scholarly work on ‘Pagan Celtic Britain’ (Ross 1967). -

LPFG Newsletter Issue 9

Later Prehistoric Finds Group Issue 9 Summer 2017 Contents Welcome to the latest edition of the LPFG newsletter. In this issue we look at an assemblage of mysterious moulds from Gussage All Saints, and a rare Late Iron Age spindle whorl from Calleva Atrebatum, the Iron Age oppidum which Welcome 2 preceded the Roman town at Silchester. Curious mould 3 matrices from The issue also contains an exclusive conversation between Helen Chittock and Gussage All Saints Elizabeth Foulds—LPFG treasurer—about Elizabeth’s new monograph, Dress and Identity in Iron Age Britain. Congratulations Elizabeth! ‘Dress and 6 Identity in Iron Age Britain’: A conversation with Dr. Elizabeth Foulds Meet the 10 committee A spindle whorl 12 from Silchester Announcements 14 Half a biconical spindle wheel from the Iron Age oppidum of Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester). Read more on page 12. Page 2 Welcome The Later Prehistoric Finds Group was established in 2013, and welcomes anyone with an interest in prehistoric artefacts, especially small finds from the Bronze and Iron Ages. We hold an annual conference and produce two newsletters a year. Membership is currently free; if you would like to join the group, please e-mail [email protected]. We are a new group, and we are hoping that more researchers interested in prehistoric artefacts will want to join us. The group has opted for a loose committee structure that is not binding, and a list of those on the steering committee, along with contact details, can be found on our website: https://sites.google.com/site/laterprehistoricfindsgroup/home. Anna Booth is the current Chair, and Dot Boughton is Deputy. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

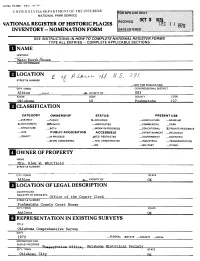

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

rnnNo. 10-300 REV. (9/77; UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC "Mato/Kosvk/House___ ______________________________________ AND/ORTSOMMOfi LOCATION STREET & NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Albion VICINITY OF 003 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Oklahoma 40 Puffhmataha 127 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) .2EPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL 2LPRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Qlen W. Whltfleld STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Albion VICINITY OF OK LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Office of the County Clerk STREET & NUMBER Pushmataha County Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Antlers OK REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS Oklahoma Comprehensive Survey DATE 1979 —FEDERAL JXSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Oklahoma Historical Society CITY. TOWN STATE Oklahoma Citv OK DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED JiUNALTERED 2LORIGINALSITE X_GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Mato Kosyk house is a small one-story, rectangular, white frame building located about three-quarters of a mile west of Albion on a gravel road. It is not entirely visible from the road, and access to it is by a private driveway leading south from the road, then west to the house lot. -

RACHEL MAXWELL-HYSLOP Rachel Maxwell-Hyslop 1914–2011

RACHEL MAXWELL-HYSLOP Rachel Maxwell-Hyslop 1914–2011 RACHEL MAXWELL-HYSLOP, the doyenne of specialists in Ancient Near Eastern jewellery and metalwork, passed away in 2011 at the age of ninety- seven. Her book on Western Asiatic jewellery, published in 1971, remains a standard work of reference after more than forty years. Rachel was born on 27 March 1914 at 11 Tite Street, Chelsea, London. She was the eldest of the three daughters of Sir Charles Travis Clay (1885–1978) and his wife Violet, second daughter of Lord Robson, Lord of Appeal. Charles Clay was appointed assistant librarian to the House of Lords in 1914 and fol- lowing active service in the First World War he was appointed librarian to the House, a post he retained until his retirement in 1956. He became an authority on medieval charters and published widely on this subject. He was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 1950 and was Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries 1934–8.1 Clay’s father, J. W. Clay, had also been a historian and genealogist, and although her grandfather died in 1918 when Rachel was a small child there was a strong family tradition of antiquarianism which Rachel evidently inherited. Rachel was educated at Downe House School near Newbury in Berkshire and at the Sorbonne in Paris where she studied French. This later stood her in good stead when together with her husband, Bill Maxwell- Hyslop, she translated from French the book by Georges Contenau that appeared in English in 1954 as Everyday Life in Babylonia and Assyria (London). -

Northern Kentucky University Board of Regents Materials

Northern Kentucky University Board of Regents Materials March 20, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS MATERIALS AGENDA March 20, 2019, Meeting Agenda ........................................................................................... 3 MINUTES January 16, 2019, Board Meeting Minutes ......................................................................... 4-13 PRESIDENTIAL REPORTS B-1) Facilities Management Report ................................................................................ 14-20 B-2) Research/Grants/Contracts Report (December 1, 2018 – January 31, 2019) ......... 21-22 B-3) Fundraising Report (July 1, 2018 – January 31, 2019) ............................................... 23 B-4) Quarterly Financial Report ..................................................................................... 24-35 B-5) Policies Report ............................................................................................................. 36 PRESIDENTIAL RECOMMENDATIONS C-1) Academic Affairs Personnel Actions ..................................................................... 37-57 C-2) Academic Affairs Reappointment, Promotion, and Tenure ................................... 58-62 C-3) Non-Academic Personnel Actions.......................................................................... 63-67 C-4) Major Gifts Acceptance .......................................................................................... 68-69 C-5) Naming Recommendations.........................................................................................