Sophia Narrett | Portfolio Sophia Narrett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Machine Embroidery Threads

Machine Embroidery Threads 17.110 Page 1 With all the threads available for machine embroidery, how do you know which one to choose? Consider the thread's size and fiber content as well as color, and for variety and fun, investigate specialty threads from metallic to glow-in-the-dark. Thread Sizes Rayon Rayon was developed as an alternative to Most natural silk. Rayon threads have the soft machine sheen of silk and are available in an embroidery incredible range of colors, usually in size 40 and sewing or 30. Because rayon is made from cellulose, threads are it accepts dyes readily for color brilliance; numbered unfortunately, it is also subject to fading from size with exposure to light or frequent 100 to 12, laundering. Choose rayon for projects with a where elegant appearance is the aim and larger number indicating a smaller thread gentle care is appropriate. Rayon thread is size. Sewing threads used for garment also a good choice for machine construction are usually size 50, while embroidered quilting motifs. embroidery designs are almost always digitized for size 40 thread. This means that Polyester the stitches in most embroidery designs are Polyester fibers are strong and durable. spaced so size 40 thread fills the design Their color range is similar to rayon threads, adequately without gaps or overlapping and they are easily substituted for rayon. threads. Colorfastness and durability make polyester When test-stitching reveals a design with an excellent choice for children's garments stitches so tightly packed it feels stiff, or other items that will be worn hard stitching with a finer size 50 or 60 thread is and/or washed often. -

Thread Yarn and Sew Much More

Thread Yarn and Sew Much More By Marsha Kirsch Supplies: • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Yarn embellishment foot set 920403096 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® 7 hole cord foot with threader 412989945 • HUSQVARNA VIKING ® Clear open toe foot 413031945 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Clear ¼” piecing foot 412927447 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Embroidery Collection # 270 Vintage Postcard • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Sensor Q foot 413192045 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER™ Royal Hoop 360X200 412944501 • INSPIRA® Cut away stabilize 141000802 • INSPIRA® Twin needles 2.0 620104696 • INSPIRA® Watercolor bobbins 413198445 • INSPIRA® 90 needle 620099496 © 2014 KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. VIKING, INSPIRA, DESIGNER and DESIGNER DIAMOND ROYALE are trademarks of KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. HUSQVARNA is a trademark of Husqvarna AB. All trademarks used under license by VSM Group AB • Warm and Natural batting • Yarn –color to match • YLI pearl crown cotton (color to match yarn ) • 2 spools of matching Robison Anton 40 wt Rayon thread • Construction thread and bobbin • ½ yard back ground fabric • ½ yard dark fabric for large squares • ¼ yard medium colored fabric for small squares • Basic sewing supplies and 24” ruler and making pen Cut: From background fabric: 14” wide by 21 ½” long From dark fabric: (20) 4 ½’ squares From medium fabric: (40) 2 ½” squares 21” W x 29” L (for backing) From Batting 21” W x 29” L From YLI Pearl Crown Cotton: Cut 2 strands 1 ¾ yds (total 3 ½ yds needed) From yarn: Cut one piece 5 yards © 2014 KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. VIKING, INSPIRA, DESIGNER and DESIGNER DIAMOND ROYALE are trademarks of KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. HUSQVARNA is a trademark of Husqvarna AB. All trademarks used under license by VSM Group AB Directions: 1. -

Our First Two Big-Time Classes

Translate Latest news from Rittenhouse Needlepoint View this email in your browser May 2018 Newsletter In this Issue: 1. Our First Two Big Time Classes 2. News roundup 3. Thread of the Month: Stef Francis 12 Ply Silk 4. Stitch of the Month: Little Wavy 5. Notes on Needlepoint Our First Two Big-Time Classes Why do I say, "Our first two big-time classes?" Well, because this is the first time in the nearly ten years that we have been open that we will be bringing in professional teachers to our store to teach. And boy are we excited! First up is "78 Stitches, 78 Threads" with Ruth Dilts. This wonderful class is a crash-course in all things Rainbow Gallery. You know Rainbow Gallery threads. You've been using them forever. They are those threads that come on cards https://us2.campaign-archive.com/?e=[UNIQID]&u=9b9b7549e5c8f818070e0508c&id=d352853db8[6/26/2018 4:17:38 PM] and are on the ubiquitous spin racks found pretty much wherever needlepoint supplies are sold. True confession here -- I've been in the business for a while now and even I have trouble keeping all the names of their products straight in my mind so I can only imagine what a jumble it must be for people who don't handle them every day. Well, now is your chance to start untangling that confusing web. And best of all with this class you will end up with a permanent reference volume to take home with you so that in the future you need never be confused by the plethora of Rainbow Gallery options ever again. -

Product Range Intro

PRODUCT RANGE INTRO The Company Page 5 Gore® Tenara® Page 31 Responsibility Page 7 Serabond Page 32 Service Page 9 N-tech Page 33 AMANN Innovation Lab Page 11 N-tech CS Page 33 A-tech CS Page 34 Nc-tech Page 35 K-tech Page 36 APPLICATION FIELDS Kc-tech Page 36 Silver-tech/Silver-tech+ Page 37 Apparel Page 12 Automotive Page 12 Shoes & Accessoires Page 12 Embroidery Page 13 SPECIAL COLOURS Home Interior Page 13 Techtex Page 13 Multicolour Page 39 Neon Page 39 INDEX AMANN PRODUCTS SPECIAL FINISHINGS Saba Page 14 Sabatex Page 15 Water-repellent (WR/WRe) Page 39 Sabaflex Page 16 Waxed (T90) Page 39 Sabasoft Page 17 For Composites (Comphil) Page 39 Serafil fine Page 18 Bonded Page 39 Rasant Page 19 MercifilGD Page 20 Strongfix Page 21 Meta Page 22 Serafil Page 23 Serabraid Page 24 Onyx Page 25 Strongbond Page 26 Isacord Page 27 Isamet Page 27 Isa Texlight Page 28 Isa/Isabob Page 28 Rasant-Oxella Page 29 Topfil Page 30 Texturan Page 30 3 THE COMPANY Since 1854, AMANN has been one of the leading global producers in the field of high-quality sewing and embroidery threads. Its technical expertise, reliability and flexibility in production and service makes AMANN a strong partner worldwide. In close cooperation with its customers, AMANN develops sewing and embroidery threads, as well as smart yarns for tomorrow's market requirements. More than 2,260 motivated employees in more than 100 countries worldwide make AMANN's success possible. AMANN Group exclusively produces at its own production sites. -

Solaris Embroidery Instruction and Reference Guide

HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL The Instruction and Reference Guides for this machine consist of the Instruction and Reference Guide (Sewing) and the Instruction and Reference Guide (Embroidery). Refer to the appropriate Instruction and Reference Guide according to your needs. For basic information about, for example, the included accessories or the settings screen, refer to chapter 1 of the Instruction and Reference Guide (Sewing). In the screens appearing in the step-by-step instructions, the parts referred to in the operations are marked with . Compare the screen in the directions with the actual screen, and carry out the operation. If, while using the machine, you experience something you do not understand, or there is a function you would like to know more about, refer to the index at the back of the Instruction and Reference Guide in conjunction with the table of contents to find the section of the manual you should refer to. 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL ............................. 1 Character Alignment............................................................ 76 Changing Font Type............................................................. 76 Chapter 1 Embroidery Step by Step 5 Changing Letter Size ............................................................ 77 Changing the Configuration of Alphabet Character Patterns... 78 BEFORE EMBROIDERING .................................... 6 Changing Alphabet Character Spacing................................. 79 Using the Machine Setting Mode Key................................... -

Medieval Clothing and Textiles

Medieval Clothing & Textiles 2 Robin Netherton Gale R. Owen-Crocker Medieval Clothing and Textiles Volume 2 Medieval Clothing and Textiles ISSN 1744–5787 General Editors Robin Netherton St. Louis, Missouri, USA Gale R. Owen-Crocker University of Manchester, England Editorial Board Miranda Howard Haddock Western Michigan University, USA John Hines Cardiff University, Wales Kay Lacey Swindon, England John H. Munro University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada M. A. Nordtorp-Madson University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, USA Frances Pritchard Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, England Monica L. Wright Middle Tennessee State University, USA Medieval Clothing and Textiles Volume 2 edited by ROBIN NETHERTON GALE R. OWEN-CROCKER THE BOYDELL PRESS © Contributors 2006 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2006 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 1 84383 203 8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library This publication is printed on acid-free paper Typeset by Frances Hackeson Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs Printed in Great Britain by Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Illustrations page vii Tables ix Contributors xi Preface xiii 1 Dress and Accessories in the Early Irish Tale “The Wooing Of 1 Becfhola” Niamh Whitfield 2 The Embroidered Word: Text in the Bayeux Tapestry 35 Gale R. -

Thread Production Bulletin Post

Bulletin Post Thread Production Contents Introduction • Raw Materials • Spinning of Polyester and Cotton Fibres • Twisting • Thread Manufacturing • Thread Types • Wet Processing • Finishing • Thread Sizing • Apparel Thread Conversion Table • Contact us about Thread Production • Introduction Sewing thread has a variety of descriptions. We generally refer to it as, "two or more yarns twisted together to form a single strand in a plied or corded construction". However, these days there are other 'Continuous Filament' constructions manufactured using technologies, like intermingling, texturising and air jet texturising which can produce a thread of a single ply construction. Coats produces many different threads and this will be explained within this technical bulletin. Most sewing threads today are based on synthetic materials, such as polyester or nylon, which have, to a large extent replaced the use of natural fibres like cotton and linen that used to be the material of choice. Handicraft threads are still predominantly made out of cotton, especially when the handicraft work is done by hand. However, if the handicraft effect is being created by a machine, (as in the case of embroidery of logos), then synthetic threads are rapidly replacing cotton and rayon threads. Bulletin Post Raw Materials A few important characteristics of the fibres and filaments which are used for sewing threads are: • Elongation at break • Elasticity and recovery • Heat resistance and flammability • Abrasion resistance • Tenacity, the strength for size of the thread Elongation at break Elasticity Heat Resistance and Abrasion resistance Tenacity and Recovery Flammability The finish is ultimately determined by the sewing performance and the lubricants used, but seam strength and seam durability is directly related to the properties mentioned above. -

An Explanatory Guide on the Unique ZWEIGART® Canvas Range 2 ZWEIGART - Made in Germany ZWEIGART - Made in Germany 3

MADE IN GERMANY CANVASES An explanatory guide on the unique ZWEIGART® canvas range 2 ZWEIGART - Made in Germany ZWEIGART - Made in Germany 3 MADE IN GERMANY Our trademark is the "Orange Line". The orange thread is woven into the edge of all the ZWEIGART® fabrics and means: Top-quality producti on. A unique range of fabrics, easy-care and woven with absolute precision: that is ZWEIGART® Made in Germany. 04 THE HISTORY OF 32 EMBROIDERY TECHNIQUES CANVASES KEY INFO ON THE TECHNIQUES THE USE OF CANVASES – HALF-STITCH . SIMPLE GOBELIN STITCH THEN AND NOW UNDERLAID HALF-STITCH GOBELIN STITCH DIAMOND STITCH 06 WHAT ARE CANVASES? DOUBLE DIAMOND STITCH PROPERTIES & SPECIAL FEATURES CROSS-STITCH AN OVERVIEW OF CANVAS BINDINGS FILLED CROSS-STITCH CARE INSTRUCTIONS STAYING STITCH IN PATTERN REPEAT RIGHT STAYING STITCH LEFT STAYING STITCH AN OVERVIEW OF ALL 08 CHESSBOARD STITCH CANVASES DIAGONAL STITCH . BASKET STITCH 500 STRAMIN VERTICAL KELIM STITCH 510 STRAMIN DIAGONAL KELIM STITCH 504 STRAMIN HORIZONTAL KELIM STITCH 505 STRAMIN MOSAIC STITCH 1231 PENELOPE CANVAS RIGHT FISHBONE DIAGONAL 1010 CAMILLA LEFT FISHBONE DIAGONAL ZWEIGART & SAWITZKI 9281 ROYAL CANVAS GmbH & Co. KG 1282 MONO CANVAS Fronäckerstraße 50 414 CORDOVA . ETAMINE 44 OTHER TECHNIQUES 71063 Sindelfi ngen 9604 ZWEIGART TWIST LATCH HOOK Germany 9699 ZWEIGART TWIST WASTE CANVAS 905 SUDANSTRAMIN POM-POM TECHNIQUE Tel + 49 (0) 7031 795 - 5 955 FEINSMYRNA . SUDAN CANVAS Fax + 49 (0) 7031 795 - 410 820 SMYRNASTRAMIN [email protected] 9106 ZWEIGART TWIST . RUG CANVAS 52 SUSTAINABILITY www.zweigart.com -

Sapphire-Jacket.Pdf

Jacket HUSQVARNA VIKING® Accessories HUSQVARNA VIKING® SAPPHIRE™ 875 Quilt Sewing Machine Gimping Foot #412 58 05-45 Gimp thread #530 37 000-11 or narrow blue cotton cord Gimping/Braiding Guide 412 55 44-45 Mini Piping Foot 413 18 30-45 Professional Touch Wand #500000905 (US # 140002559) Swarovski Crystals Pictogram Pen #412 08 38 -48 You can find these and many other accessories in the HUSQVARNA VIKING® Accessory User’s Guide or on our website www.husqvarnaviking.com, for purchase at your nearest HUSQVARNA VIKING® Dealer. (Advanced level) illu 3 illu 1 Seam allowance: Refer to sewing instructions in the pattern. Sewing Supplies: Cut out the Jacket pattern in the correct size. illu 2 Vogue pattern 8428 or your favorite jacket pattern Pattern changes for right6 front piece: Blue raw silk fabric for garment, (for amount 1. Place the front pattern pieces together, matching needed, see sewing pattern) the seam5 line. Divide the front pattern pieces into 6 illu 3 3 different blue fabrics with different textures. We different pieces.illu 1 Be sure to add 5/8" seam allowances used velvet, thai silk and organza, 16" x 36" (40 x to each4 cut edge of each piece. 90 cm). Use one of the fabrics for jacket insert and piping illu 2 3 6 Blue fabric for lining (for amount, see sewing pattern) Fusible Interfacing (for amount see sewing pattern) 2 5 1 Blue sewing thread to match the fabric 4 Blue 40 wt. rayon embroidery thread, slightly brighter than the fabric 3 Blue 30 wt. rayon embroidery thread, slightly illu 6 brighter than the fabric illu 4 2 Tear-A-Way™ Stabilizer 1 Note: The darts will not be sewn in the garment. -

Buttons to Embroider and Needle Tat Christen Brown

Buttons to Embroider and Needle Tat Christen Brown Christen Brown’s embroidered and needle-tatted buttons. Photograph by Joe Coca. C OPYRIGHT PIECEW ORK® MAGAZINE, INTERWEAVE PRESS LLC. NOT TO BE REPRINTED. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PIECEW ORK ONLINE s a child, I loved looking at pictures of my great- A grandmother in elegant lawn and lace blouses Materials fastened by ivory-colored Dorset buttons. I have been :Xife:fcc\Zk`feN`c[Õfn\ij#(''Zfkkfek_i\X[#*- fascinated with clothing and buttons since and have start- pXi[j**d &jb\`e#(jb\`e\XZ_f]')/:fe]\kk` ed to experiment with different needlework techniques to Xe['-.:\cX[fe create my own handmade buttons. I named the buttons ?XeX_J`cb9`XjI`YYfe#(`eZ_)%,Zd n`[\#(pXi[ %0d f]:_`eX;fccn`ccdXb\('Ylkkfej shown here “Tandletons,” a word derived from the tech- Af_eAXd\jE\\[c\j#j_Xigj`q\/Xe[d`cc`e\ij#j`q\* niques used, tatting and needlelace, and the function of :cfm\iJkl]Ôe^Kffc the item, a button. =X`iÔ\c[GfcpÔc#jdXccXdflek J\n`e^k_i\X[#g`eb Instructions DXk\i`XcjXi\XmX`cXYc\Xke\\[c\nfibjkfi\jfi]ifddX`c$ Note: Refer to photographs, figures, general instructions, fi[\ififec`e\i\jfliZ\j% and stitching order. * Button Base =`e`j_\[j`q\1 Ð+`eZ_(%0Zd _`^_Xe[(`eZ_)%,Zd For each base: Cut ribbon 3¼ inches (8.3 cm) long. `e[`Xd\k\i Thread sharp needle with 18 inches (45.7 cm) of sew- ing thread and knot one end. Fold length of ribbon in stitch a knot in the seam next to the edge. -

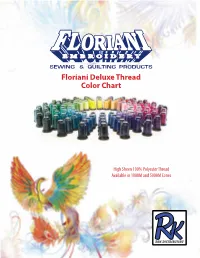

Floriani Thread Color Chart

Floriani Deluxe Thread Color Chart High Sheen 100% Polyester Thread Available in 1000M and 5000M Cones 1 Copper Black Cherry Begonia Light Pink Sangria Deep Violet PF0186 PMS 179C PF0197 PMS 195C PF1083 PMS 191C PF0102 PMS 1895C PF0139 PMS 229C PF0665 PMS 273C 2 Wildflower Old Roseleaf Shrimp Oyster Powder Puff Grape Juice PF0173 PMS 172C PF0196 PMS 506C PF1107 PMS 148C PF0100 PMS Cool Gray 1C PF0133 PMS 514C PF0696 PMS 2685 3 Burnt Orange Cabernet Grapefruit Pale Peach Roseleaf Grape Jam PF0755 PMS 166C PF1586 PMS 1815C PF0155 PMS 1925C PF0110 PMS 503C PF1902 PMS 687C PF0695 PMS 2685C 4 Orange Russet Rose Cerise Rosewater Pink Mist Tulip PF0172 PMS 165C PF0195 PMS 194C PF1082 PMS 190C PF0161 PMS 705C PF0123 PMS 2365C PF0694 PMS 2617C 5 Carrot Cherry Blush Soapstone Wisteria Amethyst PF0537 PMS 151C PF0193 PMS 194C PF0153 PMS 701C PF0163 PMS 488C PF0130 PMS 678C PF0672 PMS 2567C 6 Golden Poppy Scarlet Misty Pink Buff Bright Pink Lavender PF0535 PMS 164C PF0190 PMS 201C PF0117 PMS 701C PF1021 PMS 698C PF0125 PMS 223C PF0673 PMS 2577C 7 Bijol Burgundy Candy Pink Lace Light Lilac Light Mauve PF0526 PMS 1375C PF0194 PMS 202C PF0152 PMS 700C PF0116 PMS 496C PF0131 PMS 236C PF0674 PMS 2587C 8 Sorbet Deep Rust Champagne Light Coral Hot Pink Luxury PF0525 PMS 137C PF0192 PMS 207C PF1011 PMS 706C PF0140 PMS 169C PF0127 PMS 191C PF0675 PMS 526C 9 Apricot Hibiscus Dusty Rose Pink Rose Flamingo Royal Purple PF0533 PMS 137C PF1084 PMS 1925C PF1014 PMS 710C PF1081 PMS 707C PF0128 PMS 240C PF0676 PMS 2617C 10 Pumpkin Persimmon China Rose Pale Pink Deep -

Sewing Assistant 5-1

5. Sewing Assistant 5-1 Sewing Assistant Your Creative Assistant can be accessed at any time by tou- ching on the tool bar. Touch to open your Sewing and Embroidery Assistant. Your Sewing Assistant contains information on the most important professional sewing techniques for a wide range of fabrics, and details of which sewing machine accessories to use. The following pages explain different basic sewing techni- ques. Explore your Sewing Assistant to discover more exten- sive information about fabrics, sewing techniques and appli- cations. 5-2 5. Sewing Assistant Non-stretch seams Straight stitch Stitch no. 1 is the basic straight stitch in center needle position. The stitch length can be increased up to 6 mm as required. Some sewing techniques can be accomplished more easily by changing the needle position, such as topstitching a collar or sewing in a zipper. Your Pfaff creative 2144 features 19 needle positions, which can be adjusted with . When changing the needle position make sure that the needle is at the highest positi- on. Programmable seam length for straight stitch Stitch no. 1 Stitch no. 1 allows you to program a set seam length by tou- ching after you have touched the icon. Place the fabrics right sides together under the presser foot. Sew the first seam. When you have sewn the desired seam length, press the C reverse button. The machine will tie of at the beginning and end of the seam. You can repeat the programmed seam with the same length as often as you choose (see page 3-8 for a more detailed description).