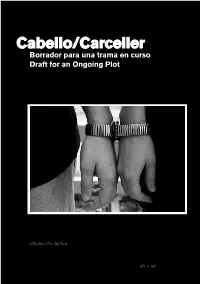

Cabello/Carceller Borrador Para Una Trama En Curso Draft for an Ongoing Plot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cabello/Carceller Borrador Para Una Trama En Curso Draft for an Ongoing Plot

Cabello/Carceller Borrador para una trama en curso Draft for an Ongoing Plot 978-84-451-3605-8 ES — EN Cabello/Carceller Borrador para una trama en curso Draft for an Ongoing Plot Presentación pág. ii — Presentation p. iii Escenario pág. 1 — Setting p. 1 Trama pág. 129 — Plot p. 129 Fuentes pág. 409 — Sources p. 409 Créditos pág. 419 — Credits p. 419 ES — EN BORRADOR PARA UNA TRAMA EN CURSO ii iii DRAFT FOR AN ONGOING PLOT Presentación Presentation Esta publicación, editada por la Comunidad de Madrid, tiene como This publication edited by the Regional Government of Madrid as- objetivo servir de referencia para un estudio global y pormenori- pires to be a reference for a comprehensive and profound study of zado del trabajo de las artistas Cabello/Carceller (París, 1963 / the work of the artists Cabello/Carceller (Paris, 1963 / Madrid, Madrid, 1964). Un volumen que recopila la intensa labor artística 1964). A book that brings together the intensive artistic work de este colectivo que, desde principios de los noventa, trabaja of the duo, who since the early 1990s have expressed a criti- sobre la crítica a las formas de identidad hegemónicas, abriendo cism of the forms of hegemonic identity, opening up the spectrum el espectro para la dignificación de las diferencias identita- by dignifying identitary differences. Cabello/Carceller propose rias. Cabello/Carceller proponen estrategias de dislocación para strategies of dislocation to directly and forcefully expose the plantear de manera directa y contundente las contradicciones del contradictions in the predominant neo-liberal model. Their oeuvre modelo neoliberal predominante. Su obra –que recoge la tradición draws on the feminist, queer, and decolonial theoretical tradi- teórica feminista, queer y decolonial– tiene como principal mate- tion and employs the body and its conflicting social and cultural ria prima el cuerpo y su contradictorio posicionamiento social y positioning as raw material. -

Lande Final Draft

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Daring to Love: A History of Lesbian Intimacy in Buenos Aires, 1966–1988 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/350586xd Author Lande, Shoshanna Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Daring to Love: A History of Lesbian Intimacy in Buenos Aires, 1966–1988 DISSERTATION submitted in partiaL satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by Shoshanna Lande Dissertation Committee: Professor Heidi Tinsman, Chair Associate Professor RacheL O’Toole Professor Jennifer Terry 2020 © 2020 Shoshanna Lande DEDICATION To my father, who would have reaLLy enjoyed this journey for me. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Abbreviations iv List of Images v AcknowLedgements vi Vita ix Abstract x Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The Secret Lives of Lesbians 23 Chapter 2: In the Basement and in the Bedroom 57 Chapter 3: TextuaL Intimacy: Creating the Lesbian Intimate Public 89 Chapter 4: After the Dictatorship: Lesbians Negotiate for their Existence 125 ConcLusion 159 Bibliography 163 iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ALMA Asociación para la Liberación de la Mujer Argentina ATEM Asociación de Trabajo y Estudio sobre la Mujer CHA Comunidad HomosexuaL Argentina CONADEP Comisión NacionaL sobre la Desaparición de Personas ERP Ejército Revolucionario deL Pueblo FAP Fuerzas Armadas Peronistas FAR Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias FIP Frente de Izquierda Popular FLH Frente de Liberación HomosexuaL FLM Frente de Lucha por la Mujer GFG Grupo Federativo Gay MLF Movimiento de Liberación Feminista MOFEP Movimiento Feminista Popular PST Partido SociaLista de Los Trabajadores UFA Unión Feminista Argentina iv LIST OF IMAGES Page Image 3.1 ELena Napolitano 94 Image 4.1 Member of the Comunidad Homosexual Argentina 126 Image 4.2 Front cover of Codo a Codo 150 v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Like any endeavor, the success of this project was possible because many people heLped me aLong the way. -

The Iconographic Turn

29 (the nude, the portrait, and images of motherhood, all seen from a certain angle, one anchored in parameters The of representation regulated first by the conventions of nineteenth-century academic art and, later, by those of early twentieth-century modernism). Artists also Iconographic engaged in systematic research on the basis of previously unexplored agendas. By means of materials, substances, and languages never before used, they Turn: undermined existing systems of representation. Their interventions revolved around a destructuring of the social formats that regulated the body. This led to the The emergence of a new body in which the former body, the culturally established body, was shattered. Denaturalized and stripped of social morality and— Denormal- more specifically—of biological function, this new conception of the body ushered in knowledge that unleashed sensibilities not previously expressed in ization of images—at least not as part of such a widespread, multiplex, and simultaneous project. That project was not tied to a single unified agenda, however, but Bodies and was formulated in different contexts on the basis of specific historically and culturally situated strategies. The body was, in general terms, at the center of Sensibilities political, social, and aesthetic agendas in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. In philosophy and theory that meant observation and analysis of the socially regulated and in the Work monitored body and of sexuality as the great narrative with which the West organized and stigmatized difference, perspectives formulated by Michel Foucault of Latin in his fundamental books Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) and The History of Sexuality (1976–84).1 Like an oil spill, that awareness of the body American spread in the cultural field and, with particular intensity, in artistic representations. -

Homotramas: Actos De Resistencia, Actos De Amor Construcción De Subjetividades Lgtb En Narraciones Del Yo Latinoamericanas

HOMOTRAMAS: ACTOS DE RESISTENCIA, ACTOS DE AMOR CONSTRUCCIÓN DE SUBJETIVIDADES LGTB EN NARRACIONES DEL YO LATINOAMERICANAS By PAOLA ARBOLEDA-RÍOS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 © 2013 Paola Arboleda-Ríos 2 To my parents and Sergio 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My infinite gratitude goes first to Dr. Efraín Barradas, my committee chair, mentor, example, and maestro. It has been an honor and a truly intellectual pleasure sharing with him the path that led to the production of this dissertation. The support of all the members of my committee has also been exceptional. I am very grateful for the close readings, sharp commentaries, and sophisticated approximation to theory of Dr. Reynaldo Jiménez, Dr. Milagros Peña, Dr. Ignacio Rodeño and Dr. Elizabeth Ginway. I am very grateful with the Professors in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese Studies, especially Dr. Andrés Avellaneda and Dr. Gillian Lord. Their challenging classes helped me become a better reader, writer, and critic. I thank my colleagues in struggle, classmates that I respect and admire immensely: Belkis Suárez, Verónica Tienza, Giovanna Rivero, Herlinda Flores, Marta Osorio and Raciel Alonso. Our conversations inside and outside the classrooms not only helped me survive graduate school, but also made my time as a Ph.D. student an intellectually demanding and personally exciting experience. I have no words to thank my mom María del Socorro-Ríos for teaching me since a very young age that I could be anything and everything I ever wished. -

“Non-Conforming” Woman: the Intersectionality of the Fight for Women's Rights and LGBTQ+ Rights in Argentin

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2021 Rights for the “Non-Conforming” Woman: The Intersectionality of the Fight for Women’s Rights and LGBTQ+ Rights in Argentina Talia C. Housman Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Legal Theory Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Housman, Talia C., "Rights for the “Non-Conforming” Woman: The Intersectionality of the Fight for Women’s Rights and LGBTQ+ Rights in Argentina" (2021). Honors Theses. 582. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/582 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rights for the “Non-Conforming” Woman: The Intersectionality of the Fight for Women’s Rights and LGBTQ+ Rights in Argentina By: Talia Housman A Proposal Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors in the Spanish Department April 7, 2021 Approved by: Adviser: ____________________________ Professor Fernando Blanco Second Evaluator in major: ____________________________ Professor Nick Jones Honors Council Representative ________________________ Professor Jennifer Kosmin Housman iv Acknowledgments: First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisors, Professor Fernando Blanco and Professor Nick Jones. Without their assistance with my many questions and dedicated involvement in every step and throughout the process, this paper would have never been accomplished. I would like to thank you very much for your support and understanding over this past year. -

Intervenciones Y Visibilidades Feministas En Las Prácticas Artísticas En Argentina (1986-2013)

Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Universidad de Buenos Aires Intervenciones y visibilidades feministas en las prácticas artísticas en Argentina (1986-2013) Tesis para optar por el título de Doctora en Ciencias Sociales Mg. María Laura Gutiérrez Director: Dr. Víctor Lenarduzzi Buenos Aires 2017 La investigación que presentamos plantea un recorrido discontinuo sobre los cruces entre prácticas artísticas, imágenes y feminismos en Argentina. Se inscribe en los debates contemporáneos que intersectan las teorías feministas en los análisis de la historia del arte, la cultura y los estudios visuales para analizar los modos en que un conjunto heterogéneo de grupos de activismo visual, artistas y colectivos activistas utilizaron estrategias artísticas y visuales como modo de invención y discusión política sexo-genérica a lo largo de treinta años, estrategias que hemos dado en llamar, siguiendo a Griselda Pollock: Intervenciones feministas. Partimos de la tesis que la articulación entre feminismos, arte y prácticas artísticas produjo un desborde del propio campo del arte en términos de un efecto político y que esa visibilidad política se constituye a través de imágenes, prácticas artísticas e intervenciones entendidas como tecnologías de género. Es decir que las intervenciones producidas por los grupos analizados no pueden ser leídas sólo en términos formales o de “representación” de obra sino, sobre todo, como procesos mismos de intervención y construcción crítica sexo-genérica. Los colectivos que analizamos son: el grupo de activismo visual Mujeres Públicas, el grupo de activismo lésbico Fugitivas/trolas del desierto, los Cuadernos de existencia lesbiana, el archivo de la memoria lésbica Potencia Tortillera, el grupo de varieté Gambas al Ajillo y la artista Liliana Maresca. -

Arte Feminista Latinoamericano

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE FACULTAD DE FILOSOFIA Y HUMANIDADES ESCUELA DE POSTGRADO ARTE FEMINISTA LATINOAMERICANO Rupturas de un arte político en la producción visual Tesis para optar al grado de Doctora en Estudios Latinoamericanos AUTORA: JULIA ANTIVILO PEÑA PROFESORA GUÍA: OLGA GRAU DUHART Santiago, marzo 2013 Agradecimientos Quiero agradecer especialmente a Mónica Mayer quien desde los inicios de esta indagación en el año 2005, cuando exploraba sobre el objeto de estudio para mi tesis de Magíster, aportó significativamente a este estudio y lo siguió haciendo en todos estos años, además de ser una de las principales protagonistas activas de la historia del arte feminista de América Latina con quien alucinamos por seguir en esta senda de impulsar más iniciativas respecto a la producción de arte feminista Latinoamericano. Asimismo toda mi gratitud a Pinto mi raya, Víctor Lerma y Mónica Mayer, por su importante archivo y la confianza depositada en mí. A Ana Victoria por sus años de ardua tarea en la recopilación archivística del movimiento feminista mexicano y de las artistas feministas mexicanas y su colaboración con este estudio. A Lorena Méndez por su interés en esta iniciativa y ayuda con los contactos. María Laura Rosa por compartir conmigo toda su investigación sobre el arte feminista en Argentina, por sus comentarios alentadores para seguir en este camino en el cual unimos fuerza. A Karen Cordero y a Josefina Alcázar por sus luces en ciertos conceptos y apoyo bibliográfico. A los/as investigadores/as colombianos Felipe González y Julián Serna por compartir desinteresadamente sus estudios sobre la artista María Teresa Hincapié, asimismo a Victoria Mahecha por cooperar a esta investigación con sus revisiones a la obra de la artista Clemencia Lucena.