Laparoscopic Liver Resection by Distance Mentoring – Trinidad to Barbados: a Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dos and Don'ts of Videoconferencing in Higher

The Dos and Don’ts of Videoconferencing in Higher Education HUSAT Research Institute Loughborough University of Technology Lindsey Butters Anne Clarke Tim Hewson Sue Pomfrett Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................3 How to use this report ..............................................................................................................3 Chapter 1 Videoconferencing in Higher Education — How to get it right ...................................5 Structure of this chapter ...............................................................................................5 Part 1 — Subject sections ............................................................................................6 Uses of videoconferencing, videoconferencing systems, the environment, funding, management Part 2 — Where are you now? ......................................................................................17 Guidance to individual users or service providers Chapter 2 Videoconferencing Services — What is Available .....................................................30 Structure of this chapter ...............................................................................................30 Overview of currently available services .......................................................................30 Broadcasting -

Broadband for Development in the ESCWA Region Enhancing Access to ICT Services in a Global Knowledge Society

Broadband for Development in the ESCWA Region Enhancing Access to ICT Services in a Global Knowledge Society Broadband for Development in the ESCWA Region Enhancing Access to ICT Services in a Global Knowledge Society Acknowledgement and Disclaimer This publication was jointly funded by UN–ESCWA and Alcatel–Lucent, with additional support for final compilation and reproduction from the United Nations Development Account proj- ect “Capacity building for ICT policymaking”. The report was super- vised by Mansour Farah, Team Leader for ICT Policies, ESCWA, and Souheil Marine, Digital Bridge Manager, Alcatel–Lucent, who defined the initial project, jointly led the publication team, contributed to the drafting of various chapters, and assured the overall quali- ty of the publication. In preparing this publication, Ayman El–Sherbiny, First Informa- tion Technology Officer in ESCWA, contributed to the drafting of var- ious chapters and acted as a focal point, defining and coordinat- ing substantive assignments between national and regional consult- ants and the publication team. Imad Sabouni, ESCWA consultant, carried out the regional analysis of case studies, compiled various contributions, and drafted core chapters. Eric Delannoy, Alcatel–Lucent consultant, also contributed to the drafting of vari- ous chapters and provided technical input. Thanks are due to Mohamed Abdel–Wahab and Mohammed Al–Wahaibi, ESCWA consultants, for their valuable contributions of case studies on Egypt and Oman respectively, and also to Habib Torbey, CEO of Globalcom Data Services, for his input on Lebanon. We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Abdulilah Dewachi, Regional Adviser on ICT, ESCWA, and to Samir Aïta, ESCWA consultant, for their review and valuable comments lead- ing to enhancements to the final drafts of the publication. -

Informed Consent for Telemedicine Services

INFORMED CONSENT FOR TELEMEDICINE SERVICES Patient Name: Date of Birth: Address: City: State: Zip: Date Consent Discussed: INTRODUCTION Telemedicine is a subset of telehealth services that uses online, interactive videoconference software to provide medical services from a distance. Private insurance companies in CT and Medicaid temporarily, are required by law to cover telemedicine health services. Telemedicine does not include the use of fax, audio-only telephone, e-mail, or videotelephony products such as FaceTime and Skype. Telemedicine involves the use of electronic communications to enable health care providers at different locations to share individual patient medical information for the purpose of improving patient care. Providers may include primary care practitioners, specialists, and/or subspecialists. The information may be used for diagnosis, therapy, follow‐up and/or education, and may include any of the following: • Patient medical records • Medical images • Live two‐way audio and video • Output data used will incorporate network and software security protocols to protect the confidentiality of patient identification to safeguard the data and to ensure its integrity against intentional or unintentional corruption EXPECTED BENEFITS • Improved access to medical care by enabling a patient to remain in his/her home (or at a remote site) while the physician obtains test results and consults from healthcare practitioners at distant/other sites • More efficient medical evaluation and management POSSIBLE RISKS As with any medical procedure, there are potential risks associated with the use of telemedicine. These risks include, but may not be limited to: • In rare cases, information transmitted may not be sufficient (e.g. poor resolution of images) to allow for appropriate medical decision making by the provider and consultant(s) | 945 Main Street Suite 205, Manchester, CT 06040 | p 860.553.3020 | f 860.553.3232 | www.emmaushealthllc.com | Page 1 of 2 Rev. -

How Can Telehealth Help in the Provision of Integrated Care?

HEALTH SYSTEMS AND POLICY ANALYSIS POLICY BRIEF 13 How can telehealth help in the provision of integrated care? Karl A. Stroetmann, Lutz Kubitschke Simon Robinson, Veli Stroetmann Kevin Cullen, David McDaid Keywords: © World Health Organization 2010 and World Health Organization, on behalf of the European Observatory TELEMEDICINE on Health Systems and Policies 2010 COMPUTER COMMUNICATION NETWORKS – utilization Address requests about publications of the WHO DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE, Regional Office for Europe to: INTEGRATED – trends Publications HEALTH POLICY WHO Regional Office for Europe COST –BENEFIT ANALYSIS Scherfigsvej 8 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for permission to quote or translate, on the Regional Office web site (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest). All rights reserved. The Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar This policy brief is one of a nature that are not mentioned. -

A Cross- Sectional Study Among Switzerland-Based Occupational

Does Therapy Always Need Touch? - A cross- sectional study among Switzerland-based occupational therapists and midwives regarding their experience with health care at a distance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spring 2020 Verena Klamroth ( [email protected] ) ZHAW: Zurcher Hochschule fur Angewandte Wissenschaften https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8944-792X Michael Gemperle ZHAW: Zurcher Hochschule fur Angewandte Wissenschaften Thomas Ballmer ZHAW: Zurcher Hochschule fur Angewandte Wissenschaften Susanne Grylka-Baeschlin ZHAW: Zurcher Hochschule fur Angewandte Wissenschaften Jessica Pehlke-Milde ZHAW: Zurcher Hochschule fur Angewandte Wissenschaften Brigitte Gantschnig ZHAW: Zurcher Hochschule fur Angewandte Wissenschaften Research article Keywords: Tele-health, tele-care, tele-rehabilitation, tele-monitoring health professions, video-telephony, technology acceptance, occupational therapy, midwifery Posted Date: November 6th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-103168/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/19 Abstract Background: The COVID-19 pandemic impedes therapy and care activities. Health care at a distance (HCD) is a promising way to ll the supply gap. However, facilitators and barriers inuence the use and experience of HCD in occupational therapists (OTs) and midwives. We identied use of services and appraisal of experiences of Switzerland-based OTs and midwives regarding the provision of HCD during the lockdown as it pertains to the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020. 1. Hypothesis: Profession, age in years, and area of work have a signicant and meaningful inuence over whether HCD is provided. 2. Hypothesis: Profession, age in years, area of work, possibility of reimbursement by health insurance, and application used have a signicant and meaningful inuence on the experience of HCD. -

Bibliography on Videotelephony and Disability 1993-2002

Stockholm Institute of Education The Disability and Handicap Research Group Bibliography on Videotelephony and Disability 1993-2002 Magnus Magnusson & Jane Brodin Research Report 36 ISSN 1102-7967 Technology, Communication, Handicap ISRN 1102-HLS-SPEC-H-36-SE FOREWORD This report is part of the work at the FUNKHA-group at Stockholm Institute of Education, The Disability and Handicap Research Group It is also a complement to an earlier report published in 1993 within the European project RACE 2033 (Research in Advanced Communications Technologies in Europe), TeleCommunity. The earlier report was a compilation of references collected from nine databases on the subject of videotelephony. That report presented comments on 190 references from 20 years of publication, most of them related to disability. It is still available and the information is still valid. The present report wishes to follow up on that earlier study, almost exactly a decade later. We have made similar literature searches in similar databases. The main difference between the present and the earlier report is the fact that the field is more difficult to grasp today because there are more information sources, expecially the Internet itself which did not exist in any extensive form at that time. This means that the present report is more focussed on projects and activities and less on formal research reports and papers. The final result in numbers, however, was almost the same as in the first study in 1993, a total number of 188 formal references. We have tried to give a short and condensed picture of the situation as we see it in the world today in this very special, promising and dynamic field. -

“Telehealth Contract” and Compliance Certification Form

Hello Thank you for reaching out to Anthem regarding telehealth. In accordance with Executive Order No. 7G, you may render and bill for telehealth services effective immediately. Providers that wish to remain telehealth eligible with Anthem following the expiration of the Executive Order will need to contracting for telehealth services by carefully reading through the Telehealth Certification Form below and simply replying back to this e-mail with the information requested at the end of the form. Anthem will review the information provided and reply back with approval including your telehealth contract effective date or with any questions/clarifications that may need to be addressed. Please note that this is only required if you wish to remain telehealth eligible following the expiration of the Executive Order. ANTHEM BLUE CROSS AND BLUE SHIELD TELEHEALTH CONTRACT AND COMPLIANCE CERTIFICATION FORM The Contracted Provider named below on this Telehealth Compliance Certification Form desires to provide “Telehealth Services” as defined and permitted under Connecticut Senate Bill 467/Public Act 15-88, or any successor bill/statute (the “Statute”) in accordance with: i) applicable law; ii) any applicable participation agreement(s) Contracted Provider holds or is subject to with Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield (“Anthem”) under the Tax Identification Number listed below (the “Participation Agreement(s)”); and iii) all applicable Anthem policies and procedures. If Contracted Provider is a group practice, then the term “Contracted Provider” applies to each member of the group practice who is eligible to provide Covered Services to members under the Participation Agreement(s) (as defined therein). The purpose of this Telehealth Compliance Certification Form is to provide assurances to Anthem that Contracted Provider will deliver Covered Services that are furnished through a telehealth medium in conformity with applicable statutory requirements. -

History Analog Video Transmission

Videotelephony - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/videotelephony/732100 (http://www.accessscience.com/) Article by: Bleiweis, John J. JJB Associates, Great Falls, Virginia. Publication year: 2014 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.732100 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.732100) Content History Infrastructure Bibliography Analog video transmission Video telephone hardware Additional Readings Digital video transmission Video telephone software A means of simultaneous, two-way communication comprising both audio and video elements. Participants in a video telephone call can both see and hear each other in real time. Videotelephony is a subset of teleconferencing, broadly defined as the various ways and means by which people communicate with one another over some distance. Initially conceived as an extension to the telephone, videotelephony is now possible using computers with network connections. In addition to general personal use, there are specific professional applications, such as criminal justice, health care delivery, and surveillance that can greatly benefit from videotelephony. See also: Teleconferencing (/content/teleconferencing/680075) History Although basic research on the technology of videotelephony dates back to 1925, the first public demonstration of the concept was by American Telephone and Telegraph Corporation (AT&T) at the 1964 New York World's Fair. The device was called Picturephone, and the high cost of the analog circuits required to support it made it very expensive and thus unsuitable for the market place. The 1970s brought the first attempts at digitization of transmissions. The video telephones comprised four parts: a standard touch-tone telephone, a small screen with a camera and loudspeaker, a control pad with user controls and a microphone, and a service unit (coder-decoder, or CODEC) that converted the analog signals to digital signals for transmission and vice versa for reception and display. -

Videoconferencing - Wikipedia,Visited the Free on Encyclopedia 6/30/2015 Page 1 of 15

Videoconferencing - Wikipedia,visited the free on encyclopedia 6/30/2015 Page 1 of 15 Videoconferencing From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Videoconferencing (VC) is the conduct of a videoconference (also known as a video conference or videoteleconference) by a set of telecommunication technologies which allow two or more locations to communicate by simultaneous two-way video and audio transmissions. It has also been called 'visual collaboration' and is a type of groupware. Videoconferencing differs from videophone calls in that it's designed to serve a conference or multiple locations rather than individuals.[1] It is an intermediate form of videotelephony, first used commercially in Germany during the late-1930s and later in A Tandberg T3 high resolution the United States during the early 1970s as part of AT&T's development of Picturephone telepresence room in use technology. (2008). With the introduction of relatively low cost, high capacity broadband telecommunication services in the late 1990s, coupled with powerful computing processors and video compression techniques, videoconferencing has made significant inroads in business, education, medicine and media. Like all long distance communications technologies (such as phone and Internet), by reducing the need to travel, which is often carried out by aeroplane, to bring people together the technology also contributes to reductions in carbon emissions, thereby helping to reduce global warming.[2][3][4] Indonesian and U.S. students Contents participating in an educational videoconference -

Rome-Bruxelles, 20 September 2011 European Commission Directorate

Rome-Bruxelles, 20 September 2011 European Commission Directorate for Competition Mergers Registry J- 70 1059 Bruxelles - Belgium by e-mail: [email protected] Observations relating to the case COMP/M.6281 — Microsoft/Skype (C 268/12 Official Journal of the European Union 10.9.2011) Need to impose interoperability of combined Skype/Microsoft services in the market of IP-to-IP voice and videotelephony services Dear Sirs, We are writing to you on behalf of Messagenet S.p.A. ( www.messagenet.it ), a fully-licensed fixed- line and VoIP telephone operator based in Italy. Messagenet, part of the COMM2000 group, is a leading Italian company in the development and on-line commercialization of Internet fax and SMS messaging as well as VoIP services, with more than 376,000 registered users, one million faxes managed per month and more than 88,000 VoIP telephone numbers assigned (January 2010). We are strongly concerned about various anticompetitive effects deriving from the proposed merger operation at stake, in particular with regard to the strengthening of the dominant position of Skype in the IP-to-IP services market and, namely, on the markets of IP-to-IP voice and video- telephony services (hereinafter together: the “Relevant Markets”). Other markets affected by the present operation are these of “Presence” and Instant Messaging (although they are not examined by the present letter). As it will be explained below, the main issue derives from the lack of interoperability of Skype IP-to- IP services with other similar services offered by third parties communications operators, which may become crucial for competition on such markets, especially with the strengthening of Skype’s position in combination with Microsoft. -

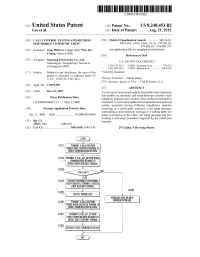

SS Display Missiocau E STABLISH VOICE OR DATA S106

USOO8248453B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8.248,453 B2 Lee et al. (45) Date of Patent: Aug. 21, 2012 (54) CALL CONTROL SYSTEMAND METHOD (58) Field of Classification Search ............... 348/1401, FORMOBILE COMMUNICATION 348/1402, 14.03, 14.04-14.16; 379/201.01, 379/202.01; 370/260–271 (75) Inventors: Jong Phil Lee, Daegu (KR); Woo Jin See application file for complete search history. Ch.ang, Gumi-si (KR(KR) (56) References Cited (73) Assignee: Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Samsung-ro, Yeongton-gu, Suwon-si, U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS Gyeonggi-do (KR) 7.359,373 B2 * 4/2008 Kuusinen et al. ............. 370,352 7,567,269 B2 * 7/2009 Sakano et al. ............. 348, 14.01 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this * cited by examiner patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S.C. 154(b) by 1341 days. Primary Examiner — Brian Ensey (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Cha & Reiter, LLC (21) Appl. No.: 11/975,501 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: Oct. 19, 2007 A call control system and method for mobile video telephony O O that enables an automatic call setup between a mobile video (65) Prior Publication Data telephony terminal and a mobile audio-dedicated terminal is US 2008/O1 OO692 A1 May 1, 2008 disclosed. A call control method for communication between mobile terminals having different capabilities includes (30) Foreign Application Priority Data receiving, at a called party terminal, a call setup message, transmitting a disconnection message to a calling party ter Oct. 31, 2006 (KR) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 10-2006-O106058 minal in response to the video call setup message and per forming a call setup procedure triggered by the called part (51) Int. -

TR 122 903 V9.0.0 (2010-01) Technical Report

ETSI TR 122 903 V9.0.0 (2010-01) Technical Report Digital cellular telecommunications system (Phase 2+); Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS); LTE; Study on Videotelephony teleservice (3GPP TR 22.903 version 9.0.0 Release 9) 3GPP TR 22.903 version 9.0.0 Release 9 1 ETSI TR 122 903 V9.0.0 (2010-01) Reference RTR/TSGS-0122903v900 Keywords GSM, LTE, UMTS ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice Individual copies of the present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org The present document may be made available in more than one electronic version or in print. In any case of existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions, the reference version is the Portable Document Format (PDF). In case of dispute, the reference shall be the printing on ETSI printers of the PDF version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: http://portal.etsi.org/chaircor/ETSI_support.asp Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission.