The Battle of Bosworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rebellion of 1483: a Study of Sources and Opinions (Part 2)

The Rebellion of 1483: A Study of Sources and Opinions (Part 2) KENNETH HILLIER NEARLY as much mystery surrounds Sir Thomas More's History of King Richard the Third'1 as the fate of the two princes! Five versions of the text survive of differing length, with the first published version (1543) being markedly altered from the 'authentic' text of over a decade later. Moreover, some question More's authorship, giving Morton a major role in the work at the very least. Alison Hanham,2 contributing to the further problem of what was More's intentions in the work, maintains it is a 'Satirical Drama'. That the book is important is not doubted: 'The work not only gives in minute detail an account of all the important events from the death of Edward IV to the outbreak of Buckingham's rebellion, but it presents the most finished portrait of Richard's person and character.'3 Certainly More's work appears (as often as any) in the footnotes of most books on Richard. The Duke of Buckingham plays a central role in the tale, from his first appearance as 'Edwarde [sic] Duke of Buckingham, and Richarde [sic] Lorde Hastinges and Chaumberlayn, both men of honour and of great power' to the last line (in Rastell's 1557 English edition) of the text, where the Bishop of Ely has planted the idea of the crown itself in his mind. Buckingham, until his rebellion, is linked with Richard throughout: he sees that Gray and Vaughan are arrested, when young Edward protests; with Rivers, they are traitors because 'they hadde contryued the destruccyon of the Dukes of Gloucester and Buckingham', whilst, later, Hastings' conspiracy was 'to have slaine ye lord protector and ye Duke of Buckingham sitting in ye counsel'. -

HVII Activity Sheet (Answers)

Welcome to the Henry VII Experience. My name is Thomas Briggs, and I lived in Micklegate Bar during the reign of Henry VII. I have set you a number of tasks to learn some information about my King Henry VII and the time period. The first one starts on the top floor. Do be careful on the stairs! Missing Letters The first challenge is to fill in the missing letters of the different armour below! K E T T L E P A D D E D G A U N T L E T H E L M E T J A C K B R E A S T P A D D E D B A R B U T E P L A T E C O I F True or False? I am sure that some of my facts are wrong. Can you please help me to work out which ones? (Put ‘true’ or ‘false’ next to the statements) 1 . Henry’s mother, Margaret Beaufort, was 14 when she gave birth to Henry TRUE 2 . The red rose was one of the badges of the House of York, and the white rose was one of the badges of the House of Lancaster FALSE 3 . Henry declared that his reign started the day before the Battle of Bosworth Field. This meant that anyone who fought against Henry in the battle could TRUE be found guilty of treason 4 . John Cabot, an Italian explorer, was sponsored by Henry VII and, in 1497, landed in mainland North America, the first European to be there since the Vikings TRUE 5 . -

History- Year 8 – the War of the Roses Time to Complete: 50 Minutes

HOME LEARNING Subject: History- Year 8 – The War of the Roses Time to complete: 50 minutes Learning Objective: To find information about the War of the Roses using a timeline. Investigate the lives of kings Henry VI and Edward IV. TASK 1: Read the information on War of the Roses. Task 2: Match each date to the King who was ruling at that time (Use the information in the timeline to help you). TASK 3: Read the information about Henry VI and Edward IV and the Battle of Towton and fill in the correct details about each king. Task 4: Watch the video clip of “Horrible Histories” showing the War of the Roses. Save your work: If you are using a computer, open a blank document to do your work (you can use Word or Publisher). Don’t forget to SAVE it with your name, the lesson you are doing and the date. For example: T.Smith Maths 8 April If you would like us to see or mark your work please email it or send a photo of your completed work to the member of staff. [email protected] TASK 1 – Read the following information about the War of the Roses THE WAR OF THE ROSES The War of the Roses was a difficult time for England. During this time 2 rich and powerful families both wanted to rule England. They had many battles against each other to try to take the crown (become King). The families were the House of Lancaster and the House of York. -

Bosworth Battlefield

BOSWORTH BATTLEFIELD A Reassessment Glenn Foard 2004 This report has been prepared by Glenn Foard FSA MIFA for Chris Burnett Associates on behalf of Leicestershire County Council. Copyright © Leicestershire County Council & Glenn Foard 2004 Cover picture: King Richard’s Field as depicted on Smith’s map of Leicestershire of 1602 Page 2 22/07/2005 BOSWORTH BATTLEFIELD A Reassessment Glenn Foard Page 3 22/07/2005 Figure 1: A view by Rimmer (1898) of the Ambion Hill site looking east, showing King Richard's Well. This is the battlefield as currently interpreted at the Battlefield Centre, which now occupies the farm in the background. Page 4 22/07/2005 CONTENTS CONTENTS.............................................................................................................................. 5 List of Illustrations.................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgements................................................................................................................... 8 Copyright .................................................................................................................................. 9 Abbreviations............................................................................................................................ 9 SUMMARY............................................................................................................................ 10 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... -

Battles and Warfare

BATTLES AND WARFARE GENERAL Le Jeu de la Hache: A Fifteenth-century Treatise on the Technique of Chivalric Axe Combat ANGLO Sydney Description: From Archaeologia, Vol. 109 Date of publication: 1991 Synopsis: Text and commentary on Le Jeu de la Hache (Bibliothèque Nationale, manuscrit français 1996), the only surviving treatise devoted exclusively to medieval axe combat. [LIBRARY NOTE: Filed under Fine and Applied Arts] The Times Guide to Battlefields of Britain ANON Description: From The Times Dates of publication: 3rd & 4th August, 1994 Synopsis: Articles on some of the battles included in English Heritage’s official new battlefields list (The Complete Guide to the Battlefields of Britain by David Smurthwaite), viz. Bannockburn, Shrewsbury, Blore Heath, Tewkesbury and Bosworth. The Wars of the Roses ANON Description: From Military History Monthly, Issue 50 Date of publication: November 2014 Synopsis: Well illustrated twenty-page editorial feature on the English civil conflicts of the fifteenth century. Includes an overview of the dynastic struggles and military campaigns, a discussion of military equipment and tactics, a longer feature on the Battle of Barnet and a brief revisionist analysis of Richard III. The strongest sections are those dealing with military matters. The brief historical explanations are, however, generally reliable, the most obvious error being the inclusion of a portrait of Elizabeth of York labelled ‘Elizabeth Woodville, Edward’s queen.’ The Wars of the Roses 1455-87 COATES Dr. J. I. Description: Typescript Date of publication: N/A Synopsis: Outline of the causes and main events of the wars. Heraldic Banners of the Wars of the Roses: Counties of Anglesey to Hampshire COVENEY Thomas Description: Freezywater Publications booklet, ed. -

Imagine Finding a Man's Whole Skeleton. Then Discovering The

Dig Imagine finding a man’s whole skeleton. Then discovering the injured bones were once King Richard III, dead since 1485. You go to work to operate the steam shovel, excavate a parking lot in Leicester and uncover the hacked bones of a despised king, the scoliosis plus evidence of battle wounds that re-open wounds and battles: who gets the bones? where should they rest? who’s legitimate? who not? The bones left long ago in a Franciscan priory fallen to disrepair since Henry VIII (heir to Richard’s killer one generation removed) separated England’s church from Rome, dissolved the monasteries seized their wealth. Now new quarrels: cities of Leicester and York both want the bones to separate tourists from their money. Queen Elizabeth II doesn’t want them in Westminster Abbey: she is, after all, the consequence of the line of succession laid down by Richard’s killer. Leicester in the midlands, where the Battle of Bosworth Field was fought, where Shakespeare’s wicked Richard cries, A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse! (and once, I’ve heard, during a performance, a drunken audience member laughed, at which the actor on stage flung out, Make haste and saddle yonder braying ass!) York to the north also claims the bones--- Richard was of the House of York, contender in the Wars of the Roses, civil and uncivil battle, dynasties fighting, Lancastrians and Yorkists--- Henry Tudor winning out at Bosworth Field. Richard and Henry were rival parts of the same royal line--- Plantagenet---different branches of one tree. -

Mike Ingram, Richard III and the Batt- Also Been Published by Kümmerle

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” 582 Mediaevistik 33 . 2020 2020 a good sense of the misery during that sie- lisher, Kümmerle, whose distribution ge and the abject poverty of the citizens network is not necessarily as global during that time. as one would like to see it. I can only James Ogier has made a great effort to hope that this will not prevent this work 00 republish this buch von der statt Triest ba- from getting a wider distribution. Even sed on the edition prepared by Hans Gille though Beheim does not necessarily re- 00 and Ingeborg Spriewald in 1971 (song no. present the highest quality in late me- 453) on the even pages and to provide an dieval German literature, he certainly 1 English translation on the uneven pages. deserves to be acknowledged and read This is by itself a very worthy enterprise more widely. Historians will also be page 582 and deserves to be greatly appreciated by pleased to have this historical poem all those working on late medieval (Ger- available again both in its original and man) literature, whether we want to grant in English. 2020 Beheim a significant role or not within Albrecht Classen the literary annals or not. There is only one major monograph in English dedi- cated to him, by William C. McDonald, “Whose Bread I Eat”, 1981), which had Mike Ingram, Richard III and the Batt- also been published by Kümmerle. With le of Bosworth. Warwick: Helion & this translation, another American Ger- Company, 2019, xxvi, 27-293 pp., b/w manist has offered a major contribution to and colored ill. -

A Machiavellian Interpretation of Henry VII

North Alabama Historical Review Volume 4 North Alabama Historical Review, Volume 4, 2014 Article 3 2014 To Keep His Subjects Low: A Machiavellian Interpretation of Henry VII John Clinton Harris University of North Alabama Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.una.edu/nahr Part of the European History Commons, and the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Harris, J. C. (2014). To Keep His Subjects Low: A Machiavellian Interpretation of Henry VII. North Alabama Historical Review, 4 (1). Retrieved from https://ir.una.edu/nahr/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNA Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Alabama Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNA Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Keep His Subjects Low: A Machiavellian Interpretation of Henry VII John Clinton Harris When Henry Tudor became Henry VII on August 22, 1485, following his victory at the Battle of Bosworth Field, many believed the anarchic course of English politics would continue unabated. The Wars of the Roses had gone on for thirty years, a period so long that intrigue, murder, and military force were now common political tools. Furthermore, there was no outward indication that Bosworth would be the last great political upheaval in the conflict; the new king was a twenty-eight year old former exile to the French court who had asserted his royal claim with nothing more than what his rival Richard III sneeringly called “a nomber of beggarly Britons and faynte harted Frenchmen.”1 The victory had only been achieved due to the fractured and distrustful state of English politics, and many, commoner and noble alike, probably wondered how long the young upstart would last before he was killed and replaced after sitting upon a bloody throne of his own. -

ALT Wars of the Roses: a Guide to the Women in Shakespeare's First Tetralogy (Especially Richard III) for Fans of Philippa Gregory's White Queen Series

Jacksonville State University JSU Digital Commons Presentations, Proceedings & Performances Faculty Scholarship & Creative Work 2021 ALT Wars of the Roses: A Guide to the Women in Shakespeare's First Tetralogy (Especially Richard III) for Fans of Philippa Gregory's White Queen Series Joanne E. Gates Jacksonville State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/fac_pres Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Other History Commons, Renaissance Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gates, Joanne E. "ALT Wars of the Roses: A Guide to the Women in Shakespeare's First Tetralogy (Especially Richard III) for Fans of Philippa Gregory's White Queen Series" (2021). Presented at SAMLA and at JSU English Department, November 2017. JSU Digital Commons Presentations, Proceedings & Performances. https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/fac_pres/5/ This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship & Creative Work at JSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations, Proceedings & Performances by an authorized administrator of JSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Joanne E. Gates: ALT Wars of the Roses: Philippa Gregory and Shakespeare, page 1 ALT Wars of the Roses: A Guide to the Women in Shakespeare's First Tetralogy (Especially Richard III) for Fans of Philippa Gregory's White Queen Series Joanne E. Gates, Jacksonville State University Since The Other Boleyn Girl made such a splash, especially with its 2008 film adaptation starring Natalie Portman and Scarlett Johansson, novelist Philippa Gregory has turned out book after book of first person female narratives, historical fiction of the era of the early Tudors and the Cousins' War. -

His 3100 Group "A" Specific Readings

His 3100 Group "a" specific readings Sources and Debates 2.3 Richard III's Proclamation against Henry (June 23, 1485) 2.4 Henry's Speech to his Army before the Battle of Bosworth Field (August 22?, 1485; from Hall's Chronicle, pub. 1548) 2.5 Trial and Execution of Perkin Warbeck and Others (November 18–December 4, 1499) 2.11 Submission of Two Ulster Chiefs (August 6 and October 1, 1541) <B>2.x The Declaration of “Richard IV” (ca. 1497)1 <hn>Like his Yorkist predecessors, Henry VII faced threats from pretenders to the throne, such as Perkin Warbeck (ca. 1474--99), a young man who claimed to be Richard, duke of York, Edward V’s younger brother, escaped from the Tower of London to reclaim his usurped throne. Compare the argument of “Richard IV” (Perkin) for his legitimacy and the illegitimacy of Henry with similar arguments in Richard III’s and Henry’s declarations of 1485. What values are appealed to? <ex>Whereas We [“Richard IV,” that is Perkin] in our tender age, escaped by God’s great might out of the Tower of London, and were secretly conveyed over the sea to divers other countries, there remaining certain years as unknown. The which season it happened one Henry son to Edmond Tydder [Tudor] -- earl of Richmond created, son to Owen Tudor of low birth in the country of Wales -- to come from France and entered into this our realm, and by subtle false means to obtain the crown of the same unto us of right appertaining: Which Henry is our extreme, and mortal enemy, as soon as he had knowledge of our being alive, imagined, compassed and wrought, all the subtle ways and means he could devise, to our final destruction, insomuch as he has not only falsely surmised us to be a feigned person, giving us nicknames, so abusing your minds; but also to deter and put us from our entry into this our realm. -

Original Text

Two Example Sections Original Text Featuring the original Shakespeare script. Visit www.classicalcomics.com to see our range of Shakespeare and Classics graphic novels. Copyright ©2010 Classical Comics Ltd. All rights reserved. Copyright notice: This downloadable resource is protected by international copyright law. Teachers and students are free to reproduce these pages by any method without infringing copyright restrictions, provided that the number of copies reproduced does not exceed the amount reasonably required for their own use. Under no circumstances can these resources be reused in whole or in part, for any commercial purposes, or for any purposes that are competitive to, or could be deemed to be in competition with, the business of Classical Comics Ltd. Adapted by: John McDonald Design/Layout by: Jo Wheeler Character Designs by: Will Sliney Artwork by: Will Sliney Lettering by: Clive Bryant Whilst all care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information provided, Classical Comics Ltd disclaims all warranties; expressed or implied, for any errors or omissions. Classical Comics Ltd are not responsible or liable for any alleged damage arising from reliance upon the information provided, which is provided “as-is” without guarantee or warranty www.classicalcomics.com Richard III Original Text RICHARD III (The Condensed Story) After the death of King Henry VI of England, the reign of the House of Lancaster ends and the House of York reclaims power under King Edward IV. Richard-Duke of Gloucester is the youngest of three brothers – the other two being King Edward IV and George-Duke of Clarence. Richard considers himself to be deformed and unsuited to peacetime. -

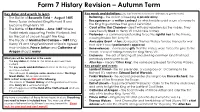

Form 6 History Revision

Form 7 History Revision – Autumn Term Key dates and events to learn Key words and definitions (you don’t need to have exact definitions to get the marks). • The Battle of Bosworth Field – August 1485 • Retaining – the action of keeping a private army. Henry Tudor defeated King Richard III and • Recognisance– a written contract by which nobles paid a sum of money to became King Henry VII the King to guarantee their good behaviour. • The Battle of East Stoke – June 1487 Where • Court of the Star Chamber– dealt with any rebellions by the nobles. They were heavily fined so Henry VII could raise money. Yorkist rebels supporting Perkin Warbeck, led • Pretender – a commoner pretending to be the rightful heir to the throne, by the Earl of Lincoln fought the King. causing trouble for Henry VII. • The Treaty of Medina Del Campo – 1489 King • Amicable Grant– A tax devised by Thomas Wolsey to raise money for war Henry VII and King Ferdinand of Spain agreed that didn’t need parliament’s approval. their children, Prince Arthur and Catherine of • Benevolences – compulsory gifts that the nobles were forced to give to the Aragon should marry. crown: a way of raising money for King Henry VIII. • Enclosure – the act of fencing off and dividing common land that had What you will be tested on in the exam: previously been open to all. • The key dates of some of the main events we have • Alter Rex – Means ‘Other King’. The name people used for Thomas Wolsey. studied. • The key words and definitions of some of the key things Key people and events we have studied.