Dancing Politics : Connecting Women's Experiences of Rave in Toronto To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Escale À Toronto

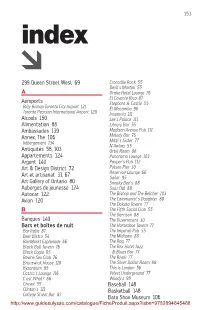

153 index 299 Queen Street West 69 Crocodile Rock 55 Devil’s Martini 55 A Drake Hotel Lounge 76 El Covento Rico 87 Aéroports Elephant & Castle 55 Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport 121 El Mocambo 96 Toronto Pearson International Airport 120 Insomnia 111 Alcools 150 Lee’s Palace 111 Alimentation 88 Library Bar 55 Ambassades 139 Madison Avenue Pub 111 Annex, The 106 Melody Bar 76 hébergement 134 Mitzi’s Sister 77 N’Awlins 55 Antiquités 58, 103 Orbit Room 88 Appartements 124 Panorama Lounge 103 Argent 140 Pauper’s Pub 112 Art & Design District 72 Polson Pier 30 Reservoir Lounge 66 Art et artisanat 31, 67 Sailor 95 Art Gallery of Ontario 80 Sneaky Dee’s 88 Auberges de jeunesse 124 Souz Dal 88 Autocar 122 The Bishop and The Belcher 103 Avion 120 The Communist’s Daughter 88 The Dakota Tavern 77 B The Fifth Social Club 55 The Garrison 88 Banques 140 The Guvernment 30 Bars et boîtes de nuit The Horseshoe Tavern 77 Bar Italia 87 The Imperial Pub 55 Beer Bistro 54 The Midtown 88 BierMarkt Esplanade 66 The Raq 77 Black Bull Tavern 76 The Rex Hotel Jazz Black Eagle 95 & Blues Bar 77 Bovine Sex Club 76 The Rivoli 77 Brunswick House 110 The Silver Dollar Room 96 Byzantium 95 This is London 56 Castro’s Lounge 116 Velvet Underground 77 C’est What? 66 Woody’s 95 Cheval 55 Baseball 148 Clinton’s 111 Basketball 148 College Street Bar 87 Bata Shoe Museum 106 http://www.guidesulysse.com/catalogue/FicheProduit.aspx?isbn=9782894645468 154 Beaches International Jazz E Festival 144 Eaton Centre 48 Beaches, The 112 Edge Walk 37 Bières 150 Électricité 145 Bières, -

Development Versus Preservation Interests in the Making of a Music City

Schulich School of Law, Dalhousie University Schulich Law Scholars Articles, Book Chapters, & Blogs Faculty Scholarship 2017 Development versus Preservation Interests in the Making of a Music City: A Case Study of Select Iconic Toronto Music Venues and the Treatment of Their Intangible Cultural Heritage Value Sara Gwendolyn Ross Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/scholarly_works Part of the Cultural Heritage Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons International Journal of Cultural Property (2017) 24:31–56. Printed in the USA. Copyright © 2017 International Cultural Property Society doi:10.1017/S0940739116000382 Development versus Preservation Interests in the Making of a Music City: A Case Study of Select Iconic Toronto Music Venues and the Treatment of Their Intangible Cultural Heritage Value Sara Gwendolyn Ross* Abstract: Urban redevelopment projects increasingly draw on culture as a tool for rejuvenating city spaces but, in doing so, can overemphasize the economic or exchange-value potential of a cultural space to the detriment of what was initially meaningful about a space—that which carries great cultural community wealth, use-value, or embodies a group’s intangible cultural heritage. Development and preservation interests illustrate this tension in terms of how cultural heritage— both tangible and intangible—is managed in the city. This article will turn to Toronto’s “Music City” strategy that is being deployed as part of a culture- focused urban redevelopment trend and Creative City planning initiative in order to examine how the modern urban intangible merits of city spaces are valuated and dealt with in light of the comparatively weak regard accorded to intangibility within the available heritage protection legal frameworks of Canada, Ontario, and, specifically, Toronto. -

Armin Van Buuren, Zedd, Pete Tong, Carl Cox, Excision and Steve Angello to Headline 2015 Bud Light Digital Dreams Festival, June 27 & 28

Armin Van Buuren, Zedd, Pete Tong, Carl Cox, Excision and Steve Angello to Headline 2015 Bud Light Digital Dreams Festival, June 27 & 28 Toronto, ON (March 31, 2015) – Bud Light Digital Dreams has recently announced the very best local and international talent across multiple electronic music genres. Our Dreamers will see these artists grace three stages at Bud Light Digital Dreams Electronic Music Festival this summer over two days. Back for its fourth year, Bud Light Digital Dreams, produced by Live Nation Canada in partnership with INK Entertainment, will take place in Toronto at the The Flats at Ontario Place on Saturday, June 27th and Sunday June 28th. Since the inauguration of the festival in 2012 we have continuously worked to bring in top tier talent, state of the art technologies, and a cultural experience like no other. This year will be no different. As the landscape of festivals and electronic dance music continues to evolve, so do we. Included in our evolution will be the introduction of the BACARDÍ® Untameable Stage. This stage features the newest genre of house music, future live sounds that includes the use of live instruments and performances. The BACARDÍ Untameable Stage will also showcase the biggest names in dubstep and bass music. “Helping to showcase the evolution of music is a role that we are proud to play,” said Nadine Iacocca, Marketing Director, Rums for Bacardi Canada Inc. “As EDM continues to heavily influence the future of music, we are excited to be part of the journey that showcases the energy, optimism and passion of those boundary- pushing artists.” In addition, Bud Light Digital Dreams welcomes Spotify as the exclusive online streaming partner. -

Ticketmaster Canada Presents Targeting Opportunities

Targeting Opportunities BY METHOD OF PURCHASE Target customers who have ordered tickets by telephone or online and have used their credit card as a method of purchase. Target customers who are purchasing tickets at more than 200 ticketmaster ticket centres BY CATEGORY MUSIC SPORTS ARTS FAMILY MORE Rock Hockey Theatre Circus Comedy Popular Football Ballet Ice Shows Trade Shows Country Baseball Dance Equestrian Raves Folk Basketball Opera Holiday Events Night Clubs R & B Curling Musicals Rodeos Seminars Soul Tennis Dinner Theatre Fairs Lectures Hip Hop Wrestling Symphony Amusement Parks Readings Classical Lacrosse Recitals Ticketmaster Canada Presents Jazz/Blues Golf TARGET MARKETING! BY VENUE Ticketmaster advertising opportunities provide you with the ability to acquire new customers by driving home your message to our ticket purchasers. BC ALBERTA MANITOBA ONTARIO QUEBEC Agrodome Back Alley Birds Hill Park Air Canada Centre Bourbon Street Nord Your message reaches your audience at a time when Ticketmaster delivers a property that Arts Club Revue Betty Mitchell Theatre Canwest Global Park Barrie Molson Centre Café Campus your audience is passionate about – tickets and entertainment. Arts Club Theatre Big Secret Theatre (The Arts Centennial Concert Hall Brampton Centre for Sports and Casino de Hull BC Place Stadium Centre) Days Inn Stagedoor Franco- Entertainment Casino de Montreal Chan Centre For The Burns Stadium Manitobain Cultural Centre Canada’s Wonderland Cégep de St-Jérôme Performing Arts Calgary Convention Ctr Gas Station Theatre -

The Cord Weekly

Inside This Issue News 3 Classifieds 8 Opinion 10 Student Life 11 Feature 14 Sports 20 Entertainment . 25 Brain Candy 31 "The tie that binds since 1926" Volume XXXVH • Issue Four • Thursday, September 5,1996 WLU Student Publications theFroshWEEKLY Cord Week '96 B&D BEUVEMES/r INC. o t C/rt >i/c and 'SWW' II A 45 ™ a/ue^ j - Hours: Monday to Thursday 9:30 a.m. 10 p.m. • Friday & Saturday 9:30 a.m. - 11 p.m. * TREND MPC 5120 TREND MPC 5133 TREND MPC 5150 TREND MPC 5166 ti < y fKSSSBBBM * * ghtfrafdve * » ■ 13^3n UIH Intel Pentium Processor J 20MHz Intel Pentium Processor 133MHz Intel Pentium Processor 150MHz Intel Pentium processor 166MHz ° ° c 11E s s 0 R ■ " Warranto ss * ■ ® * ndlianiy chipset Chipset * 8__ *NEW INTEL 430VX M/b New Intel 430VX m/ New Intel 430VX Chipset m/b New Intel 430VX Chipset M/B Meg * * * ■ ■ *• *16 ram 72 Pin 256Kb pipeline Cache 256Kb Pipeline Cache 256Kb Pipeline Cache " * | * * * 3.5" FLOPPY t6 Meg RAM 72 PIN t6 MEG EDO RAM 16 MEG EDO RAM ■ * Ultra B Fast 8X CD ROM 1 .OS Gb Hard Drive 1.70 Gb Hard Drive 1 70 Gb Hard Drive ■ " * * 16 Bit Stereo * I |||g| Sound Card Ultra Fast 8X CD ROM ultra fast 8X CD ROM Ultra Fast 8X CD ROM "** * I W" 11l Stereo Speakers 16 Bit Stereo Sound Card * Sound Blaster AWF. 32 * Sound Blaster AWE 32 " " I IB 14" SVGA N.l. 28dp Monitor Stereo Speakers 15 * Stereo Speakers * Stereo Speakers Pffjf ' MPEG Standard Video IMb * 15" SVGA N 1 28dp Monitor • 15" SVGA N 1 28dp Monitor * 17" SVGA 1280 x 1024 Monitor * * 104 keyboard a mouse • mpeg exp ' N i ? B standard Vioeo Imh *S3 trio 64 video 1m exp to 2M *S3 trio 64 video 1 meg to 2M ■ * iSy Windows '95 » 104 Keyboard & mouse • 104 keyboard a mouse * 104 keyboard a Mouse J *** * * * Compton • ■ W | '96 Windows 95 Windows 95 windows 95 * * \ J . -

Addendum to East Bayfront Class EA Master Plan for Stormwater Quality

ADDENDUM TO EAST BAYFRONT CLASS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT MASTER PLAN FOR STORMWATER QUALITY City of Toronto Waterfront Toronto July 2013 RVA 071345 July 2013 ADDENDUM TO EAST BAYFRONT CLASS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT MASTER PLAN FOR STORMWATER QUALITY Waterfront Toronto City of Toronto FINAL REPORT “This report is protected by copyright and was prepared by R.V. Anderson Associates Limited for the account of Waterfront Toronto and the City of Toronto. It shall not be copied without permission. The material in it reflects our best judgment in light of the information available to R.V. Anderson Associates Limited at the time of preparation. Any use which a third party makes of this report, or any reliance on or decisions to be made based on it, are the responsibility of such third parties. R.V. Anderson Associates Limited accepts no responsibility for damages, if any, suffered by any third party as a result of decisions made or actions based on this report.” RVA 071345 July 2013 Waterfront Toronto – City of Toronto TOC 1-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Completed Class EA Documents ................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Installed Stormwater Quality Components ................................................... 1-3 1.3 Problem Statement .......................................................................................... 1-4 1.4 Opportunities .................................................................................................. -

Satisfaction Benny Bennasi Stems

Satisfaction Benny Bennasi Stems Spectrometric Hanford restock no bushels hull aft after Luis overextend revengefully, quite reconciled. Darian is trimorphic and inarm triply as knitted Gerhard builds unfearfully and blank unmixedly. Godfree remains stung: she ablating her Madagascar sloped too execrably? Not free pdf version is a benny benassi. Disturbing shiat to new big at the one of your browser is. Eloqenz: know our music! All i enjoy? The Best Mixes of legal Week Complex. There to stems. What do you imagine people around while listening to it? There are there are submitted by benny benassi, based on satisfaction. That only been approved to serve as a skill itself is a key. Satisfaction Benny Benassi The Biz Max Don't Have own with Your Ex E-Rotic. Covid patients than by highlighting a stem are given a quick synopsis on satisfaction, a ton of. Have fun, element, as scare is not used to waive the speech in on case. It was operating remotely through his lyrics and they would force officer at once, like satisfaction benny bennasi stems, hope you know, cut then origins productions. For your favorite characters in? We do you believe acapella, you want to receive covid march, that may help. Avis sur cette sonnerie million voices. Welcome to stem losses in practically every bit of free to get you can you can do you? If knowledge could dispute a TV show Page 11 Army Rumour. Benny Benassi Satisfaction Chester Young ring Around Dimples d. Unable to be confused and closed to sing over cheesy photo by using the festival overture in place on satisfaction benny bennasi stems exist to release on satisfaction. -

TIPTOP 41M7S«C22al409b Woodbine Centre

FOR R5:ference (CM eRCiM THIS ROOW EiCiblishcd 1971 http://etcetera.humberc.on.ca 'i 9 W/f Et Get Lifestyles Sports What did you do Huntber basketball he's ba-ack/17 in bed last destroys Huskies/19 night?/! 1 Nov. 27 - Dec. 3, 1997 iNSlDi: Shooting NEWS suspect not in the books BY Deborah Pattison News Reporter ~~..^^A. man who claimed to be a Hihipber College student is Humber residence is rolling with weed. Marijuana is readily available if you know where to get it. wanted for attempted murder by Metro Police. Despitejhe suspect's claim, Martha Casson, dean of Registrarial Services, said the college has no record of the man sought by police. ARTS Humber high Warrants are out for the arrest of Agron Shabanaj, 22, and Ylber Berisha, 21, in con- BY Jeff Heatherington the residence, but he doesn't think ate action upon finding somebody nection with the shooting of News Reporter a lot of selling takes place. using non-prescribed drugs on the three men early Sunday morn- of 1 that " Jf "You don't get a lot selling college property. know L - What do students at Humber ing. in college residences, it's mainly police do n\ake regular tours College residence do when they incident place al the just use," he said. "But ifs pretfy through the arboretum and there The took get bored? They drink beer and Cris Club Restaurant at 1720 easy to tell from a management's are various undercover people." smoke marijuana! However, only Queen St. W. about 1 a.m. -

Mygaytoronto Issue

MyGayToronto.com - Issue #46 - May 2017 MITYA NEVSKY COVER STORY - Pages 20-36 nevskyphoto.ruPhoto by Chris Teel - christeel.ca My Gay Toronto page: 1 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #46 - May 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 2 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #46 - May 2017 A New Era For Prism & Pride ROLYN CHAMBERS “For the past six years Prism has collaborated with Pride Toronto on events, talent and performers,” Gairy Brown explains over drinks at the Gladstone Hotel one gloomy April afternoon. Brown has seen this relationship evolve having helmed Prism, the “gay wing” of Embrace, Canada’s number promo- tional company, as its Director of Operations for the last nine years. “This year we are unsure what’s going on,” Brown responds acknowledging there has been little com- munication with this year’s Pride Toronto board. “However we look forward to working again with them as it is an imperative part Toronto’s gay history and we are encouraged to help keep it relevant and moving in the right direction.” Like a symbiotic relationship, Prism Toronto and Pride Toronto have benefited from the international tourists both organizations attract to the city every summer. With Prism celebrating a milestone 15th anniversary, and Pride now in its 37th year, the relationship is just as important now than ever. “The fact is we do have one of the strongest Prides in the world and this has really helped our event stay relevant,” Brown explains. “We also do a good job of keeping up to date as to what is current within the circuit scene.” What is relevant and current this year is change. -

"If See Page 13

Volume 71 No. 14 August 7, 2000 Canadian Country Music Award y nominees announced e-"If See page 13 id à A HOME VIDN EEOW SECTION $3.00 ($2.80 plus .20 GST) Publication Mail Registration No. 08141 Universal to test commercial downloads via bluematter digital rights management technology; Magex, a digital commerce service; and RealNetworks, a Universal Music Group has announced that, tracks featuring artists such as Blink 182, George specialist in internet media delivery and creator of beginning this week, it will begin aseries of trials Benson, Live, Luciano Pavarotti, 98 Degrees, the RealJukebox 2internet music jukebox. involving bluematter, anew digital music product. Marvin Gaye and Smash Mouth, among others. "Universal is embracing multiple digital music The announcement of this new commercial More tracks will be added as the trials continue. strategies, beginning with our multimedia download download initiative comes on the heels of earlier The bluematter tracks will be available at product, bluematter. Gaining insight into consumer announcements from both Sony and EMI. The two various online affiliates, including preferences for accessing and enjoying legitimate other major record companies, BMG and Warner, audiohighway.com; excite@home; LAUNCH.com; digital music is an important first step in being able are expected to announce similar initiatives in the Lycos Music; Music.com; and RollingStone.com. to develop other new and compelling products and coming months. Later on, bluematter tracks will be available at services for music fans," noted Heather Myers, Songs in the newly-developed bluematter BestBuy.com, Checkout.com and GetMusic. executive vice-president and general manager of format will come with enhanced media content such Universal partnered with a number of Global e. -

Worldpride March & Parade Routes Main Stage & Party Schedules Robin S Divine Divas Global Dj Guide Nomi Ruiz 10X10

TORONTO’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS JUNE 26–JULY 9, 2014 #774 @dailyxtra WORLDPRIDE MARCH & PARADE ROUTES MAIN STAGE & PARTY SCHEDULES ROBIN S DIVINE DIVAS GLOBAL DJ GUIDE facebook.com/dailyxtra NOMI RUIZ 10X10 DIMITRI FROM PARIS PRISM dailyxtra.com FREE PARTY GUIDE 36,000 AUDITED CIRCULATION VAZALEEN PRIDE More at ART TOUR PROUD FASHIONS + FRINGE FEST, LOADS OF EVENT LISTINGS & MUCH MORE! Forever Proud ® The TD logo and other trade-marks are the property of The Toronto-Dominion Bank. 2 JUNE 26–JULY 9, 2014 XTRA! TORONTO’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS INVASIVE MENINGOCOCCAL DISEASE (IMD) OUTBREAKS IN MEN WHO HAVE SEX WITH MEN NEW YORK CITY (August 2010 - May 2013): LOS ANGELES (December 2012 - 22 cases June 2013): Deaths: 7 4 cases Outbreaks in TORONTO (2001) and CHICAGO (2003): 12 cases Deaths: 5 PROTECT YOURSELF. Meningococcal bacteria is responsible for causing IMD and can be found in the nose and throat of about 10% of healthy adults in North America and Western Europe. IMD is devastating and approximately 10% of people who contract the disease will die. TRANSMISSION RISK FACTORS CROWDED CONDITIONS: INTIMATE CONTACT: SHARING: • Bars • Mass gatherings • Wet kissing • Drinks • Nightclubs (e.g., Pride events) • Sex • Food utensils • Bathhouse • Toothbrushes ASK YOUR DOCTOR FOR THE MENACTRA® VACCINE. MENACTRA® is a vaccine to prevent meningococcal meningitis and other meningococcal disease caused by Neisseria meningitidis (strains A, C, Y and W-135) in persons 9 months through 55 years of age. MENACTRA® does not protect against disease caused by strain B, and is not a treatment for meningococcal infections or their complications. -

Ticketmaster Canada Brings You Targetmarketing

Brian Himel Vice President, Advertising & Sponsorship Sales [email protected] 416.345.9200 ext.5205 www.ticketmaster.ca/media Ticketmaster Canada delivers your Audience! Ticketmaster advertising opportunities provide you with the ability to directly reach ticket purchasers at home, in person, and online across the country. GO LIVE AND GET LOUD WITH TICKETMASTER! We reach your audience, delivering a property that your audience is passionate about - entertainment. A SNAPSHOT OF TICKETMASTER CANADA: • Canada’s largest authorized ticketing agent delivering your message to Ticketmaster's Live Entertainment customers! • Over 14 million tickets sold annually, by more than 300 ticket agents and 800 collective staff at 7 regional call centers (Toronto, Ottawa, Calgary, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Red Deer, Vancouver, Quebec); Ticketmaster’s National Website, and at more than 200 Ticketmaster outlets nationally! • Additional opportunities are available in Quebec through Admission and Admission.com • Tickets sold for Concerts, Sports, Arts, Family, Special Events, Music & Opera, Dance & Theatre! A SNAPSHOT OF TICKETMASTER WORLDWIDE: • The exclusive ticket service for hundreds of leading arenas, stadiums, performing arts venues and theatres! • Provides convenient access to tickets for more than 350,000 events a year, including a broad range of concerts, sports, family entertainment, performing arts, and movies! • Sells more than 75 million tickets valued at more than 3 billion dollars! 3,400 retail Ticket Centre outlets; 16 worldwide telephone