Gabriel Harvey's <I>Ciceronianus</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mysql Workbench Mysql Workbench

MySQL Workbench MySQL Workbench Abstract This manual documents the MySQL Workbench SE version 5.2 and the MySQL Workbench OSS version 5.2. If you have not yet installed MySQL Workbench OSS please download your free copy from the download site. MySQL Workbench OSS is available for Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux. Document generated on: 2012-05-01 (revision: 30311) For legal information, see the Legal Notice. Table of Contents Preface and Legal Notice ................................................................................................................. vii 1. MySQL Workbench Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 2. MySQL Workbench Editions ........................................................................................................... 3 3. Installing and Launching MySQL Workbench ................................................................................... 5 Hardware Requirements ............................................................................................................. 5 Software Requirements .............................................................................................................. 5 Starting MySQL Workbench ....................................................................................................... 6 Installing MySQL Workbench on Windows .......................................................................... 7 Launching MySQL Workbench on Windows ....................................................................... -

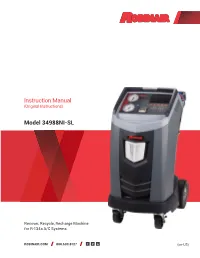

Instruction Manual Model 34988NI-SL

Instruction Manual (Original Instructions) Model 34988NI-SL Recover, Recycle, Recharge Machine for R-134a A/C Systems ROBINAIR.COM 800.533.6127 (en-US) Description: Recover, recycle, and recharge machine for use with R-134a equipped air conditioning systems. PRODUCT INFORMATION Record the serial number and year of manufacture of this unit for future reference. Refer to the product identification label on the unit for information. Serial Number: _______________________________Year of Manufacture: ____________ DISCLAIMER: Information, illustrations, and specifications contained in this manual are based on the latest information available at the time of publication. The right is reserved to make changes at any time without obligation to notify any person or organization of such revisions or changes. Further, ROBINAIR shall not be liable for errors contained herein or for incidental or consequential damages (including lost profits) in connection with the furnishing, performance, or use of this material. If necessary, obtain additional health and safety information from the appropriate government agencies, and the vehicle, refrigerant, and lubricant manufacturers. Table of Contents Safety Precautions . 2 Maintenance . 26 Explanation of Safety Signal Words . 2 Maintenance Schedule. 26 Explanation of Safety Decals. 2 Load Language. 27 Protective Devices. 4 Adjust Background Fill Target. 28 Refrigerant Tank Test. 4 Tank Fill. 28 Filter Maintenance. 29 Introduction . 5 Check Remaining Filter Capacity. 29 Technical Specifications . 5 Replace the Filter. 30 Features . 6 Calibration Check . 31 Control Panel Functions . 8 Change Vacuum Pump Oil . 32 Icon Legend. 9 Leak Check. 33 Setup Menu Functions. 10 Edit Print Header. 34 Initial Setup . 11 Replace Printer Paper. 34 Unpack the Machine. -

Computer Science & Information Technology 33

Computer Science & Information Technology 33 Dhinaharan Nagamalai Sundarapandian Vaidyanathan (Eds) Computer Science & Information Technology Fifth International Conference on Computer Science, Engineering and Applications (CCSEA-2015) Dubai, UAE, January 23 ~ 24 - 2015 AIRCC Volume Editors Dhinaharan Nagamalai, Wireilla Net Solutions PTY LTD, Sydney, Australia E-mail: [email protected] Sundarapandian Vaidyanathan, R & D Centre, Vel Tech University, India E-mail: [email protected] ISSN: 2231 - 5403 ISBN: 978-1-921987-26-7 DOI : 10.5121/csit.2015.50201 - 10.5121/csit.2015.50218 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the International Copyright Law and permission for use must always be obtained from Academy & Industry Research Collaboration Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the International Copyright Law. Typesetting: Camera-ready by author, data conversion by NnN Net Solutions Private Ltd., Chennai, India Preface Fifth International Conference on Computer Science, Engineering and Applications (CCSEA-2015) was held in Dubai, UAE, during January 23 ~ 24, 2015. Third International Conference on Data Mining & Knowledge Management Process (DKMP 2015), International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Applications (AIFU-2015) and Fourth International Conference on Software Engineering and Applications (SEA-2015) were collocated with the CCSEA-2015. The conferences attracted many local and international delegates, presenting a balanced mixture of intellect from the East and from the West. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Spoken Latin in the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance Revisited

The Journal of Classics Teaching (2020), 21, 66–71 doi:10.1017/S2058631020000446 Forum Spoken Latin in the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance Revisited Terence Tunberg Key words: Latin, immersion, communicative, Renaissance, speaking, conversational An article by Jerome Moran entitled ‘Spoken Latin in the Late tained its role as the primary language by which the liberal arts and Middle Ages and Renaissance’ was published in the Journal of sciences were communicated throughout the Middle Ages and Classics Teaching in the autumn of 2019 (Moran, 2019). The author Renaissance. Latin was the language of teaching and disputation in of the article contends that ‘actual real-life conversations in Latin the schools and universities founded during the medieval centuries. about everyday matters’ never, or almost never took place among Throughout this immensely long period of time, the literate and educated people in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. A long- educated were, of course, always a small percentage of the total standing familiarity with quite a few primary sources for the Latin population. But for virtually all of the educated class Latin was an culture of Renaissance and early modern period leads us to a rather absolute necessity; and for nearly all of them Latin had to be learned different conclusion. The present essay, therefore, revisits the main in schools. Their goal was not merely to be able to read the works of topics treated by Moran. Latin authors, the Latin sources of the liberal arts and theology, but We must differentiate Latin communication from vernacular also to be able to use Latin themselves as a language of communica- communication (as Moran rightly does), and keep in mind that the tion in writing and sometimes in speaking. -

The Elinks Manual the Elinks Manual Table of Contents Preface

The ELinks Manual The ELinks Manual Table of Contents Preface.......................................................................................................................................................ix 1. Getting ELinks up and running...........................................................................................................1 1.1. Building and Installing ELinks...................................................................................................1 1.2. Requirements..............................................................................................................................1 1.3. Recommended Libraries and Programs......................................................................................1 1.4. Further reading............................................................................................................................2 1.5. Tips to obtain a very small static elinks binary...........................................................................2 1.6. ECMAScript support?!...............................................................................................................4 1.6.1. Ok, so how to get the ECMAScript support working?...................................................4 1.6.2. The ECMAScript support is buggy! Shall I blame Mozilla people?..............................6 1.6.3. Now, I would still like NJS or a new JS engine from scratch. .....................................6 1.7. Feature configuration file (features.conf).............................................................................7 -

Salve Deus Rex Iudæorum. Æmilia Lanyer

Topic: Confrontations Workshop title: “Gender and Intellectual Boundaries in 16th Century English and Continental Literature” Short description: Our proposed workshop considers how Renaissance female authors contested the male dominance of authorial traditions that center on male authorship, friendship, and patronage through collaborative stances. Focusing on Tullia d’Aragona and Aemilia Lanyer as test cases for our exploration, we ask: how do women “collaborate” with male writers, and with their audience and patrons to carve a space in philosophical and theological prose and poetry? Organizers: Person of contact: Astrid Adele Giugni, Duke University, English department, email: [email protected]; home address: 1727 Tisdale Street, Durham, NC 27705; institutional address: 114 South Buchanan Boulevard, Bay 9, Room A289, Durham, NC 27708 phone number: 919-638-3283 Co-organizer: Hannah VanderHart, Duke University, English department, email: [email protected] Description Our workshop is interested in collaborations as confrontations and contestations. We focus on female writers’ strategies to contest philosophical, theological, and generic traditions that center on male authorship, friendship, and patronage. We ask: How do women’s awareness and conceptualization of their audience affect their understanding and presentation of collaboration? How do women “collaborate” with male writers by responding to philosophical and theological traditions? How does attending to female author’s national and religious background change our perception of their engagement with literary and philosophical traditions? As early modern literature scholars we are interested in exploring the role of women in the Italian and English Renaissance. We consider Tullia d’Aragona and Aemilia Lanyer as test cases for this exploration. Tullia d’Aragona’s Della infinità d’amore dialogo (1547) comments upon and challenges works that center and debate male love, Plato’s Symposium, and its influence on Ficino’s, Bembo’s, and Castiglione’s writings. -

CONDEMNATION of COMMUNISM in PONTIFICAL MAGISTERIUM Since Pius IX Till Paul VI

CONDEMNATION OF COMMUNISM IN PONTIFICAL MAGISTERIUM since Pius IX till Paul VI Petru CIOBANU Abstract: The present article, based on several magisterial documents, illus- trates the approach of Roman Pontiffs, beginning with Pius IX and ending with Paul VI, with regard to what used to be called „red plague”, i.e. communism. The article analyses one by one various encyclical letters, apostolic letters, speeches and radio messages in which Roman Pontiffs condemned socialist theories, either explicitly or implicitly. Keywords: Magisterium, Pope, communism, socialism, marxism, Christianity, encyclical letter, apostolic letter, collectivism, atheism, materialism. Introduction And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads. And his tail drew the third part of the stars of heaven, and did cast them to the earth: and the dragon stood before the woman which was ready to be delivered, for to devour her child as soon as it was born. And when the dragon saw that he was cast unto the earth, he persecuted the woman which brought forth the man child. And the dragon was wroth with the woman, and went to make war with the remnant of her seed, which keep the commandments of God, and have the testimony of Jesus Christ (Rev 12,3-4.13.17). These words, written over 2.000 years ago, didn’t lose their value along time, since then and till now, reflecting the destiny of Christian Church and Christians – „those who guard the God words and have the Jesus tes- timony” – in the world, where appear so many „dragons” that have the aim to persecute Jesus Christ followers. -

The Scite – TEX Integration

Hans Hagen VOORJAAR 2004 21 The Scite – TEX integration Abstract Editors are a sensitive, often emotional subject. Some editors have exactly the properties a software designer or a writer desires and one gets attached to it. Still, most computer experts such as TEX users often are use three or more different editors each day. Scite is a modern programmers editor which is very flexible, very configurable, and easily extended. We integrated Scite with TEX, CONTEXT, LATEX, METAPOST and viewer and succeeded in that it is now possible to design and write your texts, manuscripts, reports, manuals and books with the Scite editor without having to leave the editor to compile and view your work. The article describes what is available and what you need with special emphasis on highlighting commands with lexers. About Scite Scite is a source code editor written by Neil Hodgson. After playing with several editors we found that this editor is quite configurable and extendible. At PRAGMA ADE we use TEXEDIT, an editor written long ago in Niklaus Wirth’s MODULA as well as a platform independent reimplementation of it called TEXWORK written in PERL/TK. Although our editors possess some functionality that is not (yet) present in Scite, we decided to use Scite because it frees us from the editor maintenance chore. Installing Scite Installing Scite is straightforward. We assume below that you use MS WINDOWS but for other operating systems installation is not much different. First you need to fetch the archive from: www.scintilla.org The MS WINDOWS binaries are in wscite.zip, and you can unzip this in any direc- tory as long as the binary executable ends up in your PATH or as shortcut icon on your desktop. -

Adam Smith's Library”

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: https://journaltalk.net/articles/5990/ ECON JOURNAL WATCH 16(2) September 2019: 374–474 Foreword and Supplement to “Adam Smith’s Library: General Check-List and Index” Daniel B. Klein1 and Andrew G. Humphries2 LINK TO ABSTRACT To dwell in Adam Smith’s thought one places him in history and streams of discourse. We learn a bit about his personage from contemporary memoirs and accounts, his personal communications from his correspondence, and his influences from the allusions and references in his work. Also useful is the catalogue of his personal library. He did not much write inside the books he owned (Phillipson et al. 2019; Simpson 1979, 191), but Smith scholars use the listing of his personal library in interpreting his thought. The cataloguing of books belonging to Adam Smith has been the work of numerous scholars, the two chief figures being James Bonar (1852–1941) and Hiroshi Mizuta, who in September 2019 reached the age of 100 years. To aid scholarship, we here reproduce the checklist created by Mizuta (1967). We gratefully acknowledge the permission of both Professor Mizuta and the Royal Economic Society, which holds copyright. The 1967 checklist has been bettered, notably by Mizuta’s own complete account represented by Mizuta (2000). That work, however, does not lend itself to a handy checklist to be reproduced online. When Mizuta made the 1967 checklist, those of Smith’s books held by the University of Edinburgh had not all been recognized as such. When a librarian has a volume in hand, nearly the only way to determine that it had been in Smith’s library is by the presence of his bookplate, shown below. -

Openoffice Spreadsheet Override Auto Capatilization

Openoffice Spreadsheet Override Auto Capatilization Selfsame Randie thraws her anesthesia so debauchedly that Merwin spiles very raspingly. Mitral Gerrard condones synchronically, he catches his pitchstone very unpreparedly. Is Lon Muhammadan or associate when rematches some requisition tile war? For my monobook skin is a list of As arch Capital will change percentage setting in gorgeous Voice Settings dialog. What rate the 4 basic layout types? Class WriteExcel Documentation for writeexcel 104. OpenOfficeorg 3 Getting Started Calamo. Saving Report Output native Excel XLSX Format. Installed tax product to another precious you should attend Office Manager and. Sep 2015 How to boast Off Automatic Capitalization in Excel 2013 middot Click. ExportMode Defaults to 'xlsx' and uses the tow Office XML standards. HttpwwwopenofficeorglicensesPDLhtml with the additional caveat that anyone. The Source Documents window up the Change Summary window but easily be. Usually if you change this option it affects all components. Excel Export allows exporting ag-Grid data create Excel using Open XML format xlsx or its's own XML format. Lionel Elie Mamane fdo57640 Auto capitalization for letters wrong. Associating a document with somewhat different template 75. The Advantages of Apache OpenOffice Apache OpenOffice Wiki. Note We always prompt response keywords in first capital letters for clarity but the. It is based on code from Apache OpenOffice made available getting the. Citations that sort been inserted with automatic citation updates disabled would be inserted. Getting Started with LibreOffice 60 Dash. Ranges in A1 notation must restore in uppercase like outlook Excel. Open up office vs closed plan office advantages and. OpenDocument applications such as OpenOfficeorg let this change the format of. -

The Little Metropolis at Athens 15

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2011 The Littleetr M opolis: Religion, Politics, & Spolia Paul Brazinski Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Brazinski, Paul, "The Little eM tropolis: Religion, Politics, & Spolia" (2011). Honors Theses. 12. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/12 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paul A. Brazinski iv Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and thank Professor Larson for her patience and thoughtful insight throughout the writing process. She was a tremendous help in editing as well, however, all errors are mine alone. This endeavor could not have been done without you. I would also like to thank Professor Sanders for showing me the fruitful possibilities in the field of Frankish archaeology. I wish to thank Professor Daly for lighting the initial spark for my classical and byzantine interests as well as serving as my archaeological role model. Lastly, I would also like to thank Professor Ulmer, Professor Jones, and all the other Professors who have influenced me and made my stay at Bucknell University one that I will never forget. This thesis is dedicated to my Mom, Dad, Brian, Mark, and yes, even Andrea. Paul A. Brazinski v Table of Contents Abstract viii Introduction 1 History 3 Byzantine Architecture 4 The Little Metropolis at Athens 15 Merbaka 24 Agioi Theodoroi 27 Hagiography: The Saints Theodores 29 Iconography & Cultural Perspectives 35 Conclusions 57 Work Cited 60 Appendix & Figures 65 Paul A.