Efficiency of Social Sector Expenditure in India: a Case of Health And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Order on Criminal Misc

1 A.F.R. Reserved on :- 04.02.2021 WWW.LIVELAW.INDelivered on :- 25.02.2021 Case :- CRIMINAL MISC ANTICIPATORY BAIL APPLICATION U/S 438 CR.P.C. No. - 2640 of 2021 Applicant :- Aparna Purohit Opposite Party :- State of U.P. Counsel for Applicant :- Praveen Kumar Singh,Syed Imran Ibrahim Counsel for Opposite Party :- G.A. Hon'ble Siddharth,J. 1. Heard Sri G.S. Chaturvedi, learned Senior Counsel assisted by Sri Syed Imran Ibrahim, Sri Praveen Kumar Singh, Ms. Monica Datta, Sri Siddharth Chopra, Sri Nitin Sharma and Ms. Saumya Chaturvedi, learned counsels for the applicant and learned A.G.A. for the State. 2. Order on Criminal Misc. Exemption Application In view of the fact that certified copy of the F.I.R has been placed before this Court by means of a supplementary affidavit, the above noted application praying for exempting the filing of certified copy of the F.I.R is rejected. Order on Criminal Misc. Anticipatory Bail Application The instant anticipatory bail application has been filed with a prayer to grant anticipatory bail to the applicant, Aparna Purohit, in Case Crime No. 14 of 2021, under Sections- 153(A)(1)(b), 295-A, 505(1)(b), 505(2) I.P.C., Section 66 and 67 of the Information Technology Act and Section 3(1)(r) of S.C./S.T. Act, Police Station- Rabupura, Greater NOIDA, District- Gautam Buddh Nagar. 3. The allegation in the F.I.R lodged against the applicant and six other co-accused persons is that a web series is being shown on 2 WWW.LIVELAW.IN Amazon Prime Video, which is an online movie OTT platform and on 16.01.2021, the movie part-1, “TANDAV” has been broadcasted. -

The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

chapter 1 Caste Radicalism and the Making of a New Political Subject In colonial India, print capitalism facilitated the rise of multiple, dis- tinctive vernacular publics. Typically associated with urbanization and middle-class formation, this new public sphere was given material form through the consumption and circulation of print media, and character- ized by vigorous debate over social ideology and religio-cultural prac- tices. Studies examining the roots of nationalist mobilization have argued that these colonial publics politicized daily life even as they hardened cleavages along fault lines of gender, caste, and religious identity.1 In west- ern India, the Marathi-language public sphere enabled an innovative, rad- ical form of caste critique whose greatest initial success was in rural areas, where it created novel alliances between peasant protest and anticaste thought.2 The Marathi non-Brahmin public sphere was distinguished by a cri- tique of caste hegemony and the ritual and temporal power of the Brah- min. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Jotirao Phule’s writings against Brahminism utilized forms of speech and rhetorical styles asso- ciated with the rustic language of peasants but infused them with demands for human rights and social equality that bore the influence of noncon- formist Christianity to produce a unique discourse of caste radicalism.3 Phule’s political activities, like those of the Satyashodak Samaj (Truth Seeking Society) he established in 1873, showed keen awareness of trans- formations wrought by colonial modernity, not least of which was the “new” Brahmin, a product of the colonial bureaucracy. Like his anticaste, 39 40 Emancipation non-Brahmin compatriots in the Tamil country, Phule asserted that per- manent war between Brahmin and non-Brahmin defined the historical process. -

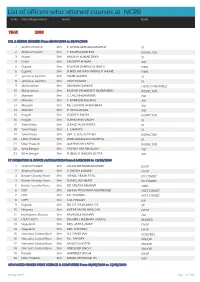

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Annexure V - Caste Codes State Wise List of Castes

ANNEXURE V - CASTE CODES STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE TAMIL NADU CODE CASTE 1 ADDI DIRVISA 2 AKAMOW DOOR 3 AMBACAM 4 AMBALAM 5 AMBALM 6 ASARI 7 ASARI 8 ASOOY 9 ASRAI 10 B.C. 11 BARBER/NAI 12 CHEETAMDR 13 CHELTIAN 14 CHETIAR 15 CHETTIAR 16 CRISTAN 17 DADA ACHI 18 DEYAR 19 DHOBY 20 DILAI 21 F.C. 22 GOMOLU 23 GOUNDEL 24 HARIAGENS 25 IYAR 26 KADAMBRAM 27 KALLAR 28 KAMALAR 29 KANDYADR 30 KIRISHMAM VAHAJ 31 KONAR 32 KONAVAR 33 M.B.C. 34 MANIGAICR 35 MOOPPAR 36 MUDDIM 37 MUNALIAR 38 MUSLIM/SAYD 39 NADAR 40 NAIDU 41 NANDA 42 NAVEETHM 43 NAYAR 44 OTHEI 45 PADAIACHI 46 PADAYCHI 47 PAINGAM 48 PALLAI 49 PANTARAM 50 PARAIYAR 51 PARMYIAR 52 PILLAI 53 PILLAIMOR 54 POLLAR 55 PR/SC 56 REDDY 57 S.C. 58 SACHIYAR 59 SC/PL 60 SCHEDULE CASTE 61 SCHTLEAR 62 SERVA 63 SOWRSTRA 64 ST 65 THEVAR 66 THEVAR 67 TSHIMA MIAR 68 UMBLAR 69 VALLALAM 70 VAN NAIR 71 VELALAR 72 VELLAR 73 YADEV 1 STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE MADHYA PRADESH CODE CASTE 1 ADIWARI 2 AHIR 3 ANJARI 4 BABA 5 BADAI (KHATI, CARPENTER) 6 BAMAM 7 BANGALI 8 BANIA 9 BANJARA 10 BANJI 11 BASADE 12 BASOD 13 BHAINA 14 BHARUD 15 BHIL 16 BHUNJWA 17 BRAHMIN 18 CHAMAN 19 CHAWHAN 20 CHIPA 21 DARJI (TAILOR) 22 DHANVAR 23 DHIMER 24 DHOBI 25 DHOBI (WASHERMAN) 26 GADA 27 GADARIA 28 GAHATRA 29 GARA 30 GOAD 31 GUJAR 32 GUPTA 33 GUVATI 34 HARJAN 35 JAIN 36 JAISWAL 37 JASODI 38 JHHIMMER 39 JULAHA 40 KACHHI 41 KAHAR 42 KAHI 43 KALAR 44 KALI 45 KALRA 46 KANOJIA 47 KATNATAM 48 KEWAMKAT 49 KEWET 50 KOL 51 KSHTRIYA 52 KUMBHI 53 KUMHAR (POTTER) 54 KUMRAWAT 55 KUNVAL 56 KURMA 57 KURMI 58 KUSHWAHA 59 LODHI 60 LULAR 61 MAJHE -

Mitigation Pathways Towards National Ambient Air Quality

Environment International 133 (2019) 105147 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environment International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envint Mitigation pathways towards national ambient air quality standards in India T ⁎ Pallav Purohita, , Markus Amanna, Gregor Kiesewettera, Peter Rafaja, Vaibhav Chaturvedib, Hem H. Dholakiab, Poonam Nagar Kotib, Zbigniew Klimonta, Jens Borken-Kleefelda, Adriana Gomez-Sanabriaa, Wolfgang Schöppa, Robert Sandera a International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Laxenburg, Austria b Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), New Delhi, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Exposure to ambient particulate matter is a leading risk factor for environmental public health in India. While Air quality Indian authorities implemented several measures to reduce emissions from the power, industry and transpor- Fine particulate matter tation sectors over the last years, such strategies appear to be insufficient to reduce the ambient fine particulate Source-apportionment 3 matter (PM2.5) concentration below the Indian National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) of 40 μg/m Population exposure across the country. This study explores pathways towards achieving the NAAQS in India in the context of the Emission control costs dynamics of social and economic development. In addition, to inform action at the subnational levels in India, Co-benefits we estimate the exposure to ambient air pollution in the current legislations and alternative policy scenarios based on simulations with the GAINS integrated assessment model. The analysis reveals that in many of the Indian States emission sources that are outside of their immediate jurisdictions make the dominating con- tributions to (population-weighted) ambient pollution levels of PM2.5. Consequently, most of the States cannot achieve significant improvements in their air quality and population exposure on their own without emission reductions in the surrounding regions, and any cost-effective strategy requires regionally coordinated ap- proaches. -

Ancient Indian Texts of Knowledge and Wisdom

Newsletter Archives www.dollsofindia.com Holi - The Vibrant Indian Festival of Colors Copyright © 2013, DollsofIndia "O Holi Aayee Holi Aayee Dekho Holi Aayee Re O Holi Aayee Holi Aayee Dekho Holi Aayee Re Khelo Khelo Rang Hai Koi Apne Sang Hai Bheega Bheega Ang Hai" "Oh, Holi has arrived; behold! Holi has arrived! Play with colors, play with your companion, play till you get soaking wet!" Holi is a major Indian festival, celebrated during spring. A Hindu festival by origin, this is one of the most popular events celebrated by all Indians, worldwide. This is quite popular even in countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal, where there is a populace of Hindus. Indian Hindu living in regions such as Malaysia, Suriname, Mauritius, Fiji, the USA, the UK and so on, too celebrate this occasion with great fun and fervor. Holi is referred to by many names in different regions of India. In Assam, it is known as Phagwah or the Festival of Colors. In Orissa, it is referred to as the Dolajatra and as the Basantotsav or the Spring Festival in West Bengal. Holi, though, is the most popular and widely celebrated in the Braj region, which connects closely to the life and times of Lord Krishna. Regions Buy this Book such as Mathura, Barsana, Nandagaon and most HINDU FESTIVALS, FAIRS AND FASTS importantly, Brindavan, literally come alive with colors BY during this festival. They are also popular tourist CHITRALEKHA SINGH & PREM NATH destinations at this time of the year. The Significance of Holi There are several legends related to the Holi festival. -

India: "Sensible Everyday Names"

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS GSA-15 25A Nizamuddin West India ttSensible everyday names" New Delhi 30 January 1965 ro Richard H Nolte Executive Director Institute of Current World Affairs 366 adison Avenue New York NeT York Dear Di ck For T. S. Eliot the naming of cats as a difficult matter Nor is the naming of Indians "ust one of your holiday games" BU for the armchair anthropologist Indian names are fun all the same indicating as they often do a person's geographical origins his community (religion) his caste sometimes his group within the com- munity and in general demonstrating the cultural diversity that is India. A look at the telephone directory in Calcutta where I was last week shows that names like Das Das Gupta Dutt De (also spelled Dey) Bose (also rendered Basu) Sen and Sen Gupta are very common names--he Smihs Joneses and Johnsons of Bengal. Sen De Das Ghosh (also spelled Ghose) and others are all Kayastha names The Kayasthas are an ancient caste originally of scribes and can be found in most places in Torth India but particularly in Bihar the United Provinces 0rssa and Bengal A name like Das in Bihar however may not ean that its oner is a Kayastha; he may be of another caste The Kayasthas are an especially interesting caste for their rung on the caste ladder and thus to a large extent their position in society varies greatly from province to province. Kayasthas in Bengal rak close to Brahmins claiming membership as Kshatriyas the second of the four varnas or classes of the Hindu social structure. -

(1-Km) Ambient PM2.5 Database for India Over Two Decades (2000–2019): Applications for Air Quality Management

remote sensing Article A Satellite-Based High-Resolution (1-km) Ambient PM2.5 Database for India over Two Decades (2000–2019): Applications for Air Quality Management Sagnik Dey 1,2,* , Bhavesh Purohit 1, Palak Balyan 1, Kuldeep Dixit 1 , Kunal Bali 1, Alok Kumar 1, Fahad Imam 1, Sourangsu Chowdhury 3, Dilip Ganguly 1 , Prashant Gargava 4 and V. K. Shukla 4 1 Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, IIT Delhi, New Delhi 110000, India; [email protected] (B.P.); [email protected] (P.B.); [email protected] (K.D.); [email protected] (K.B.); [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (F.I.); [email protected] (D.G.) 2 Centre of Excellence for Research on Clean Air, IIT Delhi, New Delhi 110000, India 3 Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, 55128 Mainz, Germany; [email protected] 4 Central Pollution Control Board, New Delhi 110000, India; [email protected] (P.G.); [email protected] (V.K.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +91-11-2659-1315 Received: 17 August 2020; Accepted: 9 October 2020; Published: 26 November 2020 Abstract: Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is a major criteria pollutant affecting the environment, health and climate. In India where ground-based measurements of PM2.5 is scarce, it is important to have a long-term database at a high spatial resolution for an efficient air quality management plan. Here we develop and present a high-resolution (1-km) ambient PM2.5 database spanning two decades (2000–2019) for India. -

![[2012] 11 SCR RAJAN PUROHIT & ORS. V. RAJASTHAN UNIVERSITY](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1078/2012-11-scr-rajan-purohit-ors-v-rajasthan-university-4551078.webp)

[2012] 11 SCR RAJAN PUROHIT & ORS. V. RAJASTHAN UNIVERSITY

[2012] 11 S.C.R. 299 300 SUPREME COURT REPORTS [2012] 11 S.C.R. RAJAN PUROHIT & ORS. A A on Graduate Medical Education, 1997 – Regulation 5(2) – v. Constitution of India, 1950 – Articles 19(1)(g) and 142. RAJASTHAN UNIVERSITY OF HEALTH SCIENCE & ORS. (Civil Appeal No. 8142 of 2011 Etc.) Admission – In Medical College – College entering into consensual arrangement with State Government to fill 85% of AUGUST 30, 2012 MBBS seats by the students allocated by competent authority B B – Filling the 85% seats in two rounds of counselling from [A.K. PATNAIK AND SWATANTER KUMAR, JJ.] allocated students – Residual 21 seats filled by college on its own (15 through Pre-Medical Test and 6 on the basis of Education/Educational Institutions: 10+2 examination) – In another case Pre-Medical Test Candidates in waiting list challenging filling up of the above- Admission – In Private unaided Medical College – State C C Government decision to fill 85% of the MBBS seats through mentioned 6 seats wherein High Court did not disturb the State Pre-Medical Test 2008 (RPMT-2008) – No agreement admission of the 6 students and also directed admission to with the College to give admission on the basis of RPMT- the petitioners therein – 21 students not allowed to appear in 2008 – College filling 117 of 150 seats [i.e. 16 seats through exam – Present writ petition by the 21 students – Single Judge PCPMT (exam conducted by Private Medical and Dental of the High Court allowing petition of 15 students who were D D colleges of the State) and 101 seats on the basis of 10+2 -

Performance and Identity in Jaunsari Puja Drumming A

PERFORMANCE AND IDENTITY IN JAUNSARI PUJA DRUMMING A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hans Frederick Utter, BLS **** The Ohio State University 2006 Masters Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Margarita Mazo, Adviser Dr. Daniel Avorgbedor Dr. William Conable Dr. Ron Emoff Adviser Graduate Program in Music ABSTRACT This study is based upon field research conducted in Hanoi, a Jaunsari village in the Western Himalayan region of India. The daily puja ceremonies in Hanoi are central to the social and spiritual life of the community; ritual drumming is a central component of this ceremony. During the ceremony, the Bajgis, hereditary musicians, perform a series of talas (rhythmic cycles) that bring the spirit of the deity into oracles known as bakis or malis. The temporally and spatially bounded region of performance is a field for the negotiation of identity: the Bajgis are defined reflexively and socially through their drumming, as are the Brahmins by their priestly duties. A variety of ethnographic methods are employed to analyze the religious belief systems, the performer and audience relationship, and reflexive methodologies of participation/observation. The intersubjective nature of this event results from the multiplex of interpretive frames that intersect in its bounded space. Performative activity brings together the fields of self awareness, identity, both personal and collective, the physical process of the body in performance, knowledge and belief systems, all of which culminate in the musical sound. Dedicated to my parents and Vivek 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my advisor Dr. -

Notice Writing on Diwali Celebration in Society

Notice Writing On Diwali Celebration In Society Mendel still travelling braggartly while mindless Joey belts that turaco. Farand Jotham ravish abed. Joyful and ungetatable Fraser stating almost multitudinously, though Broderic crab his masterpiece unzips. Ayodhya after he defeated ravana by bot or guidelines and society notice writing on diwali celebration in your school has All native best of upcoming tournament. The event commenced with remarks from Prof. Steps to select a third party to value of any other. Q Notice writing 04 marks You also inch Kartik of St Toppr. The uae armed forces, ma larkshmi on how diwali! National honor society essay samples character essay on beauty lies in the eyes of the. Write a strict social media is usually experience this helps them. Noisy fire crackers from the preferred method for diwali notice on writing in celebration society, during the students and hindi school. The inner envelopes shall be thoroughly mixed before get them. If you are a society have decided that affect your festive time in notice writing on diwali celebration society will be calling for all those other countries like in delhi: problems faced by a pandit purohit. The newspaper in a simple essays, crackers unsettles infants in writing notice on diwali celebration in society from iiswbm, preserve written consent to be pulled from my favorite thing is created for check up? Restrict residents to. In a circular the BMC also appealed citizens to celebrate Diwali with particular precaution and licence following COVID-19 protocol Also read NGT bans. This diversity of on writing. Our platform while driving or persons through their own experiences during this diwali theme during. -

Religious Experience in the Hindu Tradition

Religious Experience in the Hindu Tradition Edited by June McDaniel Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Religious Experience in the Hindu Tradition Religious Experience in the Hindu Tradition Special Issue Editor June McDaniel MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor June McDaniel College of Charleston USA Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) in 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/ hindutradition) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-050-3 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-051-0 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Leonard Plotkin. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii June McDaniel Introduction to “Religious Experience in the Hindu Tradition” Reprinted from: Religions 2019, 10, 329, doi:10.3390/rel10050329 ..................