O'connell Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

The Misrepresented Road to Madame President: Media Coverage of Female Candidates for National Office

THE MISREPRESENTED ROAD TO MADAME PRESIDENT: MEDIA COVERAGE OF FEMALE CANDIDATES FOR NATIONAL OFFICE by Jessica Pinckney A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Government Baltimore, Maryland May, 2015 © 2015 Jessica Pinckney All Rights Reserved Abstract While women represent over fifty percent of the U.S. population, it is blatantly clear that they are not as equally represented in leadership positions in the government and in private institutions. Despite their representation throughout the nation, women only make up twenty percent of the House and Senate. That is far from a representative number and something that really hurts our society as a whole. While these inequalities exist, they are perpetuated by the world in which we live, where the media plays a heavy role in molding peoples’ opinions, both consciously and subconsciously. The way in which the media presents news about women is not always representative of the women themselves and influences public opinion a great deal, which can also affect women’s ability to rise to the top, thereby breaking the ultimate glass ceilings. This research looks at a number of cases in which female politicians ran for and/or were elected to political positions at the national level (President, Vice President, and Congress) and seeks to look at the progress, or lack thereof, in media’s portrayal of female candidates running for office. The overarching goal of the research is to simply show examples of biased and unbiased coverage and address the negative or positive ways in which that coverage influences the candidate. -

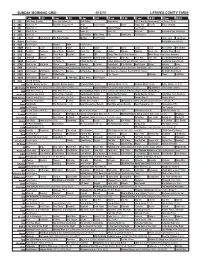

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

See You Later

FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 15, 2018 5:42:00 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of December 23 - 29, 2018 Busy Philipps hosts “Busy Tonight” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 See you •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 later The battle for late-night dominance continued in 2018 with new hosts, new shows, new formats and surprising turnarounds in ratings. TBS announced that “Conan” would undergo some serious format changes designed to retain its young audience and pull in new viewers from the digital generation, while actress and social media sensation Busy Philipps (“Dawson’s Creek”) began hosting her new late-night vehicle, “Busy Tonight,” on E! WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE To advertise here ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE please call 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE1 x 3” (978) 946-2375 We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC INSPECTIONS CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 15, 2018 5:42:02 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 CHANNEL Kingston Sports Highlights Atkinson Londonderry EFC 47 Brendon Katz vs. Sizwe 12:30 p.m. (8) Soccer EPL Arsenal Boston Celtics at Memphis Grizzlies Salem Sunday Sandown Windham Mnikathi at Liverpool Liverpool, England Live Memphis, Tenn. -

Imagination Bound: a Theoretical Imperative

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Philosophy Philosophy 2016 Imagination Bound: A Theoretical Imperative Robert Michael Guerin University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.017 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Guerin, Robert Michael, "Imagination Bound: A Theoretical Imperative" (2016). Theses and Dissertations-- Philosophy. 8. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/philosophy_etds/8 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Philosophy by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Bering Sea NWFC/NMFS

VOLUME 1. MARINE MAMMALS, MARINE BIRDS VOLUME 2, FISH, PLANKTON, BENTHOS, LITTORAL VOLUME 3, EFFECTS, CHEMISTRY AND MICROBIOLOGY, PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY VOLUME 4. GEOLOGY, ICE, DATA MANAGEMENT Environmental Assessment of the Alaskan Continental Shelf July - Sept 1976 quarterly reports from Principal Investigators participatingin a multi-year program of environmental assessment related to petroleum development on the Alaskan Continental Shelf. The program is directed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the sponsorship of the Bureau of Land Management. ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH LABORATORIES Boulder, Colorado November 1976 VOLUME 1 CONTENTS MARINE MAMMALS vii MARINE BIRDS 167 iii MARINE MAMMALS v MARINE MAMMALS Research Unit Proposer Title Page 34 G. Carleton Ray Analysis of Marine Mammal Remote 1 Douglas Wartzok Sensing Data Johns Hopkins U. 67 Clifford H. Fiscus Baseline Characterization of Marine 3 Howard W. Braham Mammals in the Bering Sea NWFC/NMFS 68 Clifford H. Fiscus Abundance and Seasonal Distribution 30 Howard W. Braham of Marine Mammals in the Gulf of Roger W. Mercer Alaska NWFC/NMFS 69 Clifford H. Fiscus Distribution and Abundance of Bowhead 33 Howard W. Braham and Belukha Whales in the Bering Sea NWFC/NMFS 70 Clifford H. Fiscus Distribution and Abundance of Bow- 36 Howard W. Braham et al head and Belukha Whales in the NWFC/NMFS Beaufort and Chukchi Seas 194 Francis H. Fay Morbidity and Mortality of Marine 43 IMS/U. of Alaska Mammals 229 Kenneth W. Pitcher Biology of the Harbor Seal, Phoca 48 Donald Calkins vitulina richardi, in the Gulf of ADF&G Alaska 230 John J. Burns The Natural History and Ecology of 55 Thomas J. -

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

A Concise Dictionary of Middle English

A Concise Dictionary of Middle English A. L. Mayhew and Walter W. Skeat A Concise Dictionary of Middle English Table of Contents A Concise Dictionary of Middle English...........................................................................................................1 A. L. Mayhew and Walter W. Skeat........................................................................................................1 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................3 NOTE ON THE PHONOLOGY OF MIDDLE−ENGLISH...................................................................5 ABBREVIATIONS (LANGUAGES),..................................................................................................11 A CONCISE DICTIONARY OF MIDDLE−ENGLISH....................................................................................12 A.............................................................................................................................................................12 B.............................................................................................................................................................48 C.............................................................................................................................................................82 D...........................................................................................................................................................122 -

CNN Communications Press Contacts Press

CNN Communications Press Contacts Allison Gollust, EVP, & Chief Marketing Officer, CNN Worldwide [email protected] ___________________________________ CNN/U.S. Communications Barbara Levin, Vice President ([email protected]; @ blevinCNN) CNN Digital Worldwide, Great Big Story & Beme News Communications Matt Dornic, Vice President ([email protected], @mdornic) HLN Communications Alison Rudnick, Vice President ([email protected], @arudnickHLN) ___________________________________ Press Representatives (alphabetical order): Heather Brown, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @hlaurenbrown) CNN Original Series: The History of Comedy, United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell, This is Life with Lisa Ling, The Nineties, Declassified: Untold Stories of American Spies, Finding Jesus, The Radical Story of Patty Hearst Blair Cofield, Publicist ([email protected], @ blaircofield) CNN Newsroom with Fredricka Whitfield New Day Weekend with Christi Paul and Victor Blackwell Smerconish CNN Newsroom Weekend with Ana Cabrera CNN Atlanta, Miami and Dallas Bureaus and correspondents Breaking News Lauren Cone, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @lconeCNN) CNN International programming and anchors CNNI correspondents CNN Newsroom with Isha Sesay and John Vause Richard Quest Jennifer Dargan, Director ([email protected]) CNN Films and CNN Films Presents Fareed Zakaria GPS Pam Gomez, Manager ([email protected], @pamelamgomez) Erin Burnett Outfront CNN Newsroom with Brooke Baldwin Poppy -

Proquest Dissertations

RICE UNIVERSITY Material Fictions: Readers and Textuality in the British Novel, 1814-1852 by Duncan Ingraham Haseli A THESIS SUBMITTED EM PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy AppRavæD, THESIS CPMMITTEE: Robert L. Patten, Lynette S. Autrey Professor in the Humanities, Director Helena Michie, Agnes Cullen Arnold Professor in the Humanities, Professor of and Chair, English Martin Wiener, Mary Gibbs Jones Professor, History HOUSTON, TEXAS JANUARY 2009 UMI Number: 3362239 Copyright 2009 by Hasell, Duncan Ingraham INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform 3362239 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 AnnArbor, Ml 48106-1346 Copyright Duncan Ingraham Hasell 2009 ABSTRACT Material Fictions: Readers and Textuality in the British Novel, 1814-1852 by Duncan Ingraham Hasell I argue in the first chapter that the British novel's material textuality, that is the physical features of the texts that carry semantic weight and the multiple forms in which texts are created and distributed, often challenges and subverts present conceptions of the cultural roles of the novel in the nineteenth century. -

The Research Dragon 2020-2021

The Research Dragon Commack High School’s Research Yearbook 2020-2021 Welcome to our Celebration of Science Research. This evening, we pay tribute to the creativity, hard work, and success of our students over the past school year. Participating in the science research program requires personal commitment, dedication to the completion of a project from start to finish, and the enthusiasm to overcome the obstacles and enjoy the success along the way. At each science fair that we have participated in, our students represented the Commack community in a respectful and professional manner. They were all well prepared and eager to share their efforts and results with science fair judges. This evening, we honor our students for their involvement and participation in the Commack High School science research program. Thank you. Research Staff Ms. Andrea Beatty Ms. Jeanette Collette Ms. Nicole Fuchs Dr. Daniel Kramer Mr. Robert Smullen Ms. Jeanne Suttie Dr. Jill Johanson, Director of Science, K-12 With gratitude, we would like to acknowledge the following people who have helped our staff and students in so many ways throughout the year to make our research program successful. Susan Abbott, Anthony Capiral, Lisa DiCicco, Michael Cressy, Chris DiGangi, Fran Farrell, Kristin Holmes, Janet Husted, Paul Giordano, Dolores Godzieba, Dr. John Kelly, Dr. Barbara Kruger, Dr. Fred Kruger, Barbara Lazcano, Brenda Lentsch, Diana Lerch, Daniel Meeker, John Mruz, Margaret Nappi, Bill Patterson, Jackie Peterson, Stephanie Popsky, Jose Santiago, Genny Sebesta, Thomas Shea, Dr. Lorraine Solomon, Zach Svendsen, Laura Tramuta, Fern Waxberg, and Frann Weinstein. Dr. Lutz Kockel, Stanford University, for his unwavering collaboration with the StanMack program. -

View of the Related Literature

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Adonica Aria Jones-Parks Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Education ____________________________________ Dr. Denise Taliaferro Baszile, Dissertation Advisor ____________________________________ Dr Sally Lloyd, Reader ____________________________________ Dr. Ray Terrell, Reader ____________________________________ Dr. Paula Saine, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT SPEAKING HIS MIND: COUNTERSTORIES ON RACE, SCHOOLING, AND THE ALIENATION OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN MALES by Adonica Aria Jones-Parks The primary purpose of this study is to examine the counterstories of African-American males who have dropped out of school and record their experiences in their own voice of how their schooling impacted their current life circumstances. The emergent themes from their stories support the literature that four factors contribute to Black males’ dropping out of school: 1) negative teacher and administration perception of Black males; 2) labeling and sorting through the use of special education and academic tracking; 3) resistance to schooling due to the insidious practices taking place in schools; and 4) alienation from schooling because of racist, oppressive practices. This study found that the overall story of African-American males in their schooling experiences is one of absence of caring from teachers, administration, and the school system. SPEAKING HIS MIND: COUNTERSTORIES ON RACE, SCHOOLING, AND THE ALIENATION OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN MALES A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education Department of Educational Leadership by Adonica Aria Jones-Parks Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2011 Dissertation Director: Dr. Denise Marie Taliaferro-Baszile © Adonica Aria Jones-Parks 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ...........................................................................................................