Halevy and the Politics of the Talmud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

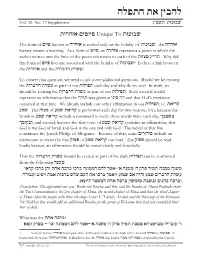

Azharos-Piyuttim Unique to Shavuos

dltzd z` oiadl Vol. 10 No. 17 Supplement b"ryz zereay zexdf`-miheit Unique To zereay The form of heit known as dxdf` is recited only on the holiday of 1zereay. An dxdf` literary means: a warning. As a form of heit, an dxdf` represents a poem in which the author weaves into the lines of the poem references to each of the zeevn b"ixz. Why did this form of heit become associated with the holiday of zereay? Is there a link between the zexdf` and the zexacd zxyr? To answer that question, we need to ask some additional questions. Should we be reciting the zexacd zxyr as part of our zelitz each day and why do we not? In truth, we should be reciting the zexacd zxyr as part of our zelitz. Such a recital would represent an affirmation that the dxez was given at ipiq xd and that G-d’s revelation occurred at that time. We already include one other affirmation in our zelitz; i.e. z`ixw rny. The devn of rny z`ixw is performed each day for two reasons; first, because the words in rny z`ixw include a command to recite these words twice each day, jakya jnewae, and second, because the first verse of rny z`ixw contains an affirmation; that G-d is the G-d of Israel and G-d is the one and only G-d. The recital of that line constitutes the Jewish Pledge of Allegiance. Because of that, some mixeciq include an instruction to recite the first weqt of rny z`ixw out loud. -

Foreword, Abbreviations, Glossary

FOREWORD, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY The Soncino Babylonian Talmud TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES Reformatted by Reuven Brauner, Raanana 5771 1 FOREWORDS, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY Halakhah.com Presents the Contents of the Soncino Babylonian Talmud TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES, GLOSSARY AND INDICES UNDER THE EDITORSHIP OF R AB B I D R . I. EPSTEIN B.A., Ph.D., D. Lit. FOREWORD BY THE VERY REV. THE LATE CHIEF RABBI DR. J. H. HERTZ INTRODUCTION BY THE EDITOR THE SONCINO PRESS LONDON Original footnotes renumbered. 2 FOREWORDS, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY These are the Sedarim ("orders", or major There are about 12,800 printed pages in the divisions) and tractates (books) of the Soncino Talmud, not counting introductions, Babylonian Talmud, as translated and indexes, glossaries, etc. Of these, this site has organized for publication by the Soncino about 8050 pages on line, comprising about Press in 1935 - 1948. 1460 files — about 63% of the Soncino Talmud. This should in no way be considered The English terms in italics are taken from a substitute for the printed edition, with the the Introductions in the respective Soncino complete text, fully cross-referenced volumes. A summary of the contents of each footnotes, a master index, an index for each Tractate is given in the Introduction to the tractate, scriptural index, rabbinical index, Seder, and a detailed summary by chapter is and so on. given in the Introduction to the Tractate. SEDER ZERA‘IM (Seeds : 11 tractates) Introduction to Seder Zera‘im — Rabbi Dr. I Epstein INDEX Foreword — The Very Rev. The Chief Rabbi Israel Brodie Abbreviations Glossary 1. -

On Telling the Truth and Avoiding Deception Rabbi Daniel S Alexander Rosh Hashanah Day II

On Telling the Truth and Avoiding Deception Rabbi Daniel S Alexander Rosh Hashanah Day II During the recent series of commemorations following the death of Senator John McCain, I relished reviewing the scene from that town hall meeting in Lakeville, MN back in October of 2008. It was a period when racist conspiracies about then Senator Obama were being circulated in some social media outlets. In the now famous scene, a woman wearing a red, McCain-Palin tee shirt takes the microphone and begins, “I can’t trust Obama. I have read about him, and he’s not, um, um….” At this point, McCain begins to nod his head up and down in apparent enjoyment of the support. The woman continues, “… he’s an Arab.” Without a moment’s hesitation, McCain removes the microphone from his erstwhile supporter and interjects: “No, ma’am. He’s a decent family man [and a] citizen that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues, and that’s what the campaign’s all about. He’s not [an Arab].” In that swift microphone removal and that unconsidered “No, ma’am …” McCain acted on what could only have been an instinct for integrity, a reflex to avoid deception and to speak truth. The rabbinic sages of our Jewish tradition have much to say about speaking truth and avoiding deception. Sometimes they teach in the language of law and sometimes in the language of story. Altogether, they present us with useful touchstones for a consideration of this timely topic, timely both as it pertains to the serious challenge posed ever more relentlessly in the contemporary political discourse to which we have been subjected in recent months and also because of the imperative on these Days of Awe to engage in a serious process of self judgment and self correction. -

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

Facilitator's Guide

Facilitator’s Guide A Project of the Aleph Society The Global Day of Jewish Learning A project of the Aleph Society © 2011 by The Aleph Society All Rights Reserved 25 West 45th Street, Suite 1405 New York, New York 10036 212.840.1166 www.steinsaltz.org www.theglobalday.com TABLE OF CONTENTS www.theglobalday.com Shema: The Unity of Jewish People Facilitator’s Guide 2011 An Overview for Facilitators and Educators ............................................................................................. 3 Using the Curriculium Guidebook for all Levels ..................................................................................... 6 Shema o Shema: An Introduction and Overview ................................................................................................................ 9 o Bedtime Shema: A conversation for parents & bedtime rituals .......................................................................... 15 o Advanced Class: The Shema’s Place in Jewish Liturgy ......................................................................................... 22 The Lord is Our God & The Lord is One o Exploring Our Ideas about God .............................................................................................................................. 30 o The Challenge of Idolatry ........................................................................................................................................ 38 o Monotheism and Oneness ..................................................................................................................................... -

Mishnah: the New Scripture Territories in the East

176 FROM TEXT TO TRADITION in this period was virtually unfettered. The latter restriction seems to have been often compromised. Under the Severan dynasty (193-225 C.E.) Jewish fortunes improved with the granting of a variety of legal privileges culminating in full Roman citizenship for Jews. The enjoyment of these privileges and the peace which Jewry enjoyed in the Roman Empire were·· interrupted only by the invasions by the barbarians in the West 10 and the instability and economic decline they caused throughout the empire, and by the Parthian incursions against Roman Mishnah: The New Scripture territories in the East. The latter years of Roman rule, in the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba Revolt and on the verge of the Christianization of the empire, were extremely fertile ones for the development of . The period beginning with the destruction (or rather, with the Judaism. It was in this period that tannaitic Judaism came to its restoration in approximately 80 C.E.) saw a fundamental change final stages, and that the work of gathering its intellectual in Jewish study and learning. This was the era in which the heritage, the Mishnah, into a redacted collection began. All the Mishnah was being compiled and in which many other tannaitic suffering and the fervent yearnings for redemption had culmi traditions were taking shape. The fundamental change was that nated not in a messianic state, but in a collection of traditions the oral Torah gradually evolved into a fixed corpus of its own which set forth the dreams and aspirations for the perfect which eventually replaced the written Torah as the main object holiness that state was to engender. -

Melilah Agunah Sptib W Heads

Agunah and the Problem of Authority: Directions for Future Research Bernard S. Jackson Agunah Research Unit Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester [email protected] 1.0 History and Authority 1 2.0 Conditions 7 2.1 Conditions in Practice Documents and Halakhic Restrictions 7 2.2 The Palestinian Tradition on Conditions 8 2.3 The French Proposals of 1907 10 2.4 Modern Proposals for Conditions 12 3.0 Coercion 19 3.1 The Mishnah 19 3.2 The Issues 19 3.3 The talmudic sources 21 3.4 The Gaonim 24 3.5 The Rishonim 28 3.6 Conclusions on coercion of the moredet 34 4.0 Annulment 36 4.1 The talmudic cases 36 4.2 Post-talmudic developments 39 4.3 Annulment in takkanot hakahal 41 4.4 Kiddushe Ta’ut 48 4.5 Takkanot in Israel 56 5.0 Conclusions 57 5.1 Consensus 57 5.2 Other issues regarding sources of law 61 5.3 Interaction of Remedies 65 5.4 Towards a Solution 68 Appendix A: Divorce Procedures in Biblical Times 71 Appendix B: Secular Laws Inhibiting Civil Divorce in the Absence of a Get 72 References (Secondary Literature) 73 1.0 History and Authority 1.1 Not infrequently, the problem of agunah1 (I refer throughout to the victim of a recalcitrant, not a 1 The verb from which the noun agunah derives occurs once in the Hebrew Bible, of the situations of Ruth and Orpah. In Ruth 1:12-13, Naomi tells her widowed daughters-in-law to go home. -

A Comparative Study of Jewish Commentaries and Patristic Literature on the Book of Ruth

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF JEWISH COMMENTARIES AND PATRISTIC LITERATURE ON THE BOOK OF RUTH by CHAN MAN KI A Dissertation submitted to the University of Pretoria for the degree of PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR Department of Old Testament Studies Faculty of Theology University of Pretoria South Africa Promoter: PIETER M. VENTER JANUARY, 2010 © University of Pretoria Summary Title : A comparative study of Jewish Commentaries and Patristic Literature on the Book of Ruth Researcher : Chan Man Ki Promoter : Pieter M. Venter, D.D. Department : Old Testament Studies Degree :Doctor of Philosophy This dissertation deals with two exegetical traditions, that of the early Jewish and the patristic schools. The research work for this project urges the need to analyze both Jewish and Patristic literature in which specific types of hermeneutics are found. The title of the thesis (“compared study of patristic and Jewish exegesis”) indicates the goal and the scope of this study. These two different hermeneutical approaches from a specific period of time will be compared with each other illustrated by their interpretation of the book of Ruth. The thesis discusses how the process of interpretation was affected by the interpreters’ society in which they lived. This work in turn shows the relationship between the cultural variants of the exegetes and the biblical interpretation. Both methodologies represented by Jewish and patristic exegesis were applicable and social relevant. They maintained the interest of community and fulfilled the need of their generation. Referring to early Jewish exegesis, the interpretations upheld the position of Ruth as a heir of the Davidic dynasty. They advocated the importance of Boaz’s and Ruth’s virtue as a good illustration of morality in Judaism. -

Of Selected Amoraim/Saboraim

INDEX OF SELECTED AMORAIM/SABORAIM Abuha de-Shmuel n. 190, 95–97, 66, 95–97 and activity in Nehardea 4 n. 6 n. 269 R. Adda b. Ahava I chronological location 37–43 chronological location 112 confused with “the Nehardean pupil of Rav 112 say” 42–43 R. Adda b. Ahava (Abba) II confused with Amemar bar Mar chronological location 112 n. 69 Yanuka 41 pupil of Rava 112 n. 69 confused with R. Yemar 41 R. Adda b. Minyumi died during R. Ashi’s lifetime 40–41 chronological location 148 n. 115 geographical location 44–45 subject to the authority of halakhic rulings in actual Rabina 148 n. 115 cases 55–66 R. Aha b. Jacob halakhic rulings issued in Nehardea and the exilarch 135 67–82 chronological location 133–136 halakhic rulings issued in Sura, does not interact with second and Mahoza or Pumbedita 55–56 third generation amoraim 134 interpretation of tannaitic present in R. Huna’s pirka 136–138 sources 84–91, 93–94 and n. 256 quotes halakhic tradition in the legal methodology compared name of third generation with Nehardean amoraim 84 amoraim 133–134 (Samuel, R. Sheshet, subordinates to R. Nahman 133 R. Nahman), 92–93 and n. 252 and n. 26 (R. Zebid of Nehardea), 176 superior to R. Aha son of (R. Zebid of Nehardea), 193 R. Ika 135–136 (R. Dimi of Nehardea) superior to R. Elazar of Hagrunya literary contribution compared with and R. Aha b. Tahlifa 136 sages from his generation 84–85, superior to R. Papa/Papi 135 93–94 n. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Orthodox Divorce in Jewish and Islamic Legal Histories

Every Law Tells a Story: Orthodox Divorce in Jewish and Islamic Legal Histories Lena Salaymeh* I. Defining Wife-Initiated Divorce ................................................................................. 23 II. A Judaic Chronology of Wife-Initiated Divorce .................................................... 24 A. Rabbinic Era (70–620 CE) ............................................................................ 24 B. Geonic Era (620–1050 CE) ........................................................................... 27 C. Era of the Rishonim (1050–1400 CE) ......................................................... 31 III. An Islamic Chronology of Wife-Initiated Divorce ............................................... 34 A. Legal Circles (610–750 CE) ........................................................................... 34 B. Professionalization of Legal Schools (800–1050 CE) ............................... 37 C. Consolidation (1050–1400 CE) ..................................................................... 42 IV. Disenchanting the Orthodox Narratives ................................................................ 44 A. Reevaluating Causal Influence ...................................................................... 47 B. Giving Voice to the Geonim ......................................................................... 50 C. Which Context? ............................................................................................... 52 V. An Interwoven Narrative of Wife-Initiated Divorce ............................................ -

Guarding Oral Transmission: Within and Between Cultures

Oral Tradition, 25/1 (2010): 41-56 Guarding Oral Transmission: Within and Between Cultures Talya Fishman Like their rabbinic Jewish predecessors and contemporaries, early Muslims distinguished between teachings made known through revelation and those articulated by human tradents. Efforts were made throughout the seventh century—and, in some locations, well into the ninth— to insure that the epistemological distinctness of these two culturally authoritative corpora would be reflected and affirmed in discrete modes of transmission. Thus, while the revealed Qur’an was transmitted in written compilations from the time of Uthman, the third caliph (d. 656), the inscription of ḥadīth, reports of the sayings and activities of the Prophet Muhammad and his companions, was vehemently opposed—even after writing had become commonplace. The zeal with which Muslim scholars guarded oral transmission, and the ingenious strategies they deployed in order to preserve this practice, attracted the attention of several contemporary researchers, and prompted one of them, Michael Cook, to search for the origins of this cultural impulse. After reviewing an array of possible causes that might explain early Muslim zeal to insure that aḥadīth were relayed solely through oral transmission,1 Cook argued for “the Jewish origin of the Muslim hostility to the writing of tradition” (1997:442).2 The Arabic evidence he cites consists of warnings to Muslims that ḥadīth inscription would lead them to commit the theological error of which contemporaneous Jews were guilty (501-03): once they inscribed their Mathnā, that is, Mishna, Jews came to regard this repository of human teachings as a source of authority equal to that of revealed Scripture (Ibn Sacd 1904-40:v, 140; iii, 1).3 As Jewish evidence for his claim, Cook cites sayings by Palestinian rabbis of late antiquity and by writers of the geonic era, which asserted that extra-revelationary teachings are only to be relayed through oral transmission (1997:498-518).