5 Eisenhower, Sputnik, and the Creation of PSAC, 1957

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

The 1960 Presidential Election in Florida: Did the Space Race and the National Prestige Issue Play an Important Role?

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2000 The 1960 rP esidential Election in Florida: Did the Space Race and the National Prestige Issue Play an Important Role? Randy Wade Babish University of North Florida Suggested Citation Babish, Randy Wade, "The 1960 rP esidential Election in Florida: Did the Space Race and the National Prestige Issue Play an Important Role?" (2000). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 134. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/134 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2000 All Rights Reserved THE 1960 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN FLORIDA: DID THE SPACE RACE AND THE NATIONAL PRESTIGE ISSUE PLAY AN IMPORTANT ROLE? by Randy Wade Babish A thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES December, 2000 Unpublished work © Randy Wade Babish The thesis of Randy Wade Babish is approved: (Date) Signature Deleted Signature Deleted Signature Deleted Signature Deleted Accepted for the College: Signature Deleted Signature Deleted eanofGfaduate rues ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Although my name appears on the title page and I assume full responsibility for the final product and its content, the quality of this work was greatly enhanced by the guidance of several individuals. First, the members of my thesis committee, Dr. -

Day 6: Comparing Themes Across Texts English Language Arts

Day 6: Comparing Themes Across Texts English Language Arts • Analyze the primary source quotes of Apollo 1 astronauts prior to their tragic deaths. Attempt to find a common theme that relates to the previous themes • Additional Resource Video: Apollo 1 Mission Results in Space Changes https://bit.ly/2DXV9gs The Apollo 1 Mission Videos of Quotes from the Apollo 1 Astronauts: https://ctm.americanexperience.org Directions: Consider the words of the following NASA astronauts who were scheduled to lift off in Apollo 1 on February 21, 1967. Virgil “Gus” Grissom: There's always a possibility that you can have a catastrophic failure, of course. This can happen on any flight. It can happen on the last one as well as the first one. You just plan as best you can to take care of all these eventualities, and you get a well-trained crew, and you go fly. Ed White: "I think you have to understand the feeling that a pilot has, that a test pilot has, that I look forward a great deal to making the first flight. There's a great deal of pride involved in making a first flight." (The New York Times, January 29, 1967, p. 48.) Roger Chaffee: “Oh, I don’t like to say anything scary about it. Um, there’s a lot of unknowns of course and a lot of problems that could develop, might develop. And they’ll have to be solved and that’s what we’re there for.” During a test launch approximately a month before their scheduled launch into space, these men suffered a tragic death when they were locked inside of their command module when a fire broke out aboard the ship. -

Into the Unknown Together the DOD, NASA, and Early Spaceflight

Frontmatter 11/23/05 10:12 AM Page i Into the Unknown Together The DOD, NASA, and Early Spaceflight MARK ERICKSON Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 2005 Frontmatter 11/23/05 10:12 AM Page ii Air University Library Cataloging Data Erickson, Mark, 1962- Into the unknown together : the DOD, NASA and early spaceflight / Mark Erick- son. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-140-6 1. Manned space flight—Government policy—United States—History. 2. National Aeronautics and Space Administration—History. 3. Astronautics, Military—Govern- ment policy—United States. 4. United States. Air Force—History. 5. United States. Dept. of Defense—History. I. Title. 629.45'009'73––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the editor and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public re- lease: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii Frontmatter 11/23/05 10:12 AM Page iii To Becky, Anna, and Jessica You make it all worthwhile. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Frontmatter 11/23/05 10:12 AM Page v Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii DEDICATION . iii ABOUT THE AUTHOR . ix 1 NECESSARY PRECONDITIONS . 1 Ambling toward Sputnik . 3 NASA’s Predecessor Organization and the DOD . 18 Notes . 24 2 EISENHOWER ACT I: REACTION TO SPUTNIK AND THE BIRTH OF NASA . 31 Eisenhower Attempts to Calm the Nation . -

Timeline of Key Events - Paper 2 - the Cold War

Timeline of Key Events - Paper 2 - The Cold War Revision Activities - Remembering the chronological order and specific dates of events is an important skill in IBDP History and can help you to organise the flow of events and how they are connected. Study the timeline of key events below, taken from the IBDP specification, to test yourself. Origins of the Cold War 1943-1949 - Global Spread of the Cold War 1945-1964 - Reconciliation and Renewed Conflict 1963-1979 - The End of the Cold War 1939 24 August - The Nazi-Soviet Pact is signed between Germany and the USSR. Italy was only informed two days before the Pact. Each pledged to remain neutral in the event of either nation being attacked by a third party. Its secret protocols divided Northern and Eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence. Poland was divided between the two. 1 September - Germany invades Poland at 4.45am, starting the European War with Italy declaring itself a non-belligerent. 3 September - Britain and France declare war on Germany. 1940 9 April - German troops invade Denmark and Norway in order to secure Swedish coal and steel supplies. 10 May - Germany invades Holland, Belgium and France simultaneously, ending the Phoney War in the West. 10 May - Winston Churchill becomes UK Prime Minister after the resignation of Neville Chamberlain. 1941 11 March - The US Lend-Lease Act launched a programme for supplying Britain and other allies with ‘surplus’ armaments in return for bases. Over $50 billion in supplies were given, ending any pretense of neutrality. 22 June - Operation Barbarossa begins as Germany invades the USSR. -

Ike's Missile Crisis

4/12/20198:1901 AM University of Washington Libraries Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery Services Box 352900 - Seattle, WA 98195-2900 (206) 543-1878 Document Delivery [email protected] w WAU 1 WAUWAS 1 RAPID:WAU Scan Seattle SCAN FOR COURSE INSTRUCTION ILLiad TN: 1747933 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 Location: Suzzallo and Allen Libraries Stacks Call #: E835 .H56 2018 Loansome Doc: Work Order Location: n 1111111111 Journal Title: The Age of Eisenhower Customer Reference: Volume: Billing Category: Issue: Chapter 15 Needed By: 10-10-2099 Month/Year: ,2018 Maximum Cost: Pages: 376-406 Article Author: Wiliam Hitchcock NOTICE OF COPYRIGHT Article Title: The document above is being supplied to you in accordance with ISSN: 9781439175668 United States Copyright Law (Title 17 US Code). It is intended only OCLC #: for your personal research or instructional use. The document may not be posted to the web or retransmitted in electronic form. Distribution or copying in any form requires the prior express written consent of the copyright owner and payment of royalties Infringement of copyright law may subject the violator to civil fine andlor criminal prosecution. Special Instructions: ScanforCanvas Notes/Alternate Delivery: Email: [email protected] EMAIL: [email protected] ILLiad CHAPTER 15 IKE'S MISSILE CRISIS "The world must stop the present plunge toward more and more destructive weapons of war:' I THE FIGHT OVER THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1957, FOLLOWED by the bitter clash in Little Rock, left Eisenhower reeling and unsteady. His political fortunes sagged further when, in August 1957, the nation's economy slipped into a short, sharp recession. -

Higher Education in Wartime and the Development of National Defense

The First Line of Defense: Higher Education in Wartime and the Development of National Defense Education, 1939-1959 Dana Adrienne Ponte a dissertation to be submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON 2016 Reading Committee: Maresi Nerad, Chair Nancy Beadie Bill Zumeta Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Educational Leadership & Policy Studies ©Copyright 2016 Dana Adrienne Ponte Abstract This study posits that the National Defense Education Act of 1958 (NDEA) represented the culmination of nearly a century-long process through which education was linked to national defense in periods of wartime, and later retained a strategic utility for defense purposes in times of peace. That a defense rationale for federal support of public higher education achieved a staying power that outlasted moments of temporary strategic necessity is due in large part to the efforts of individuals in the education and policymaking communities who were able to envision and promote a lasting, expansive definition of education for national defense – one that would effectively marshal federal funding for decades to come. In the latter half of the 20th century, it was precisely this definition that provided the rationale for further federal forays into public education in the United States, accumulating into a level of involvement that now feels commonplace. Despite its present predominance, however, this relationship was by no means a foregone conclusion in the early decades of the 20th century. The United States has historically been defined by its constitutional separation of federal and state powers, notably made manifest in a traditional emphasis on state control over public education. -

Legislative Origins of the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958

LEGISLATIVE ORIGINS OF THE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ACT OF 1958 Proceedings of an Oral History Workshop Conducted April 3, 1992 LEGISLATIVE ORIGINS OF THE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ACT OF 1958 Proceedings of an Oral History Workshop Conducted April 3, 1992 Moderated by John M. Logsdon MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY Number 8 National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA History Office Office of Policy and Plans Washington, DC 1998 Contents Forewor d . .iii Preface and Acknowledgments . .v Introduction . .vii Individual Discussions George E. Reedy . .1 Willis H. Shapley . .6 Gerald W. Siegel . .11 Glen P. Wilson . .16 H. Guyford Stever . .21 Paul G. Dembling . .25 Eilene Galloway . .30 Roundtable Discussion . .37 Appendices “How the U.S. Space Act Came to Be,” by Glen P. Wilson . .49 “Additional Comments,” by Eilene Galloway . .57 “National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958” . .61 Index . .75 Forewor d n retrospect, it appears that the Soviet launch of Sputniks 1 and 2 in the autumn of 1957 took place at exactly the right time to inspire the U.S. entrance into the space age. The ingredients were in place Ito begin space exploration already, but the Sputnik crisis prompted important legislation that brought many of these elements together into a single organization. By striking a blow at U.S. prestige, the Sputnik crisis had the effect of unifying groups that had been working separately on space missions, national defense, arms control, and within national and international organizations. The National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 was a tangible result of that national unification and accomplished one fundamental objective: it ensured that outer space would be a dependable, orderly place for benefi- cial pursuits. -

Eisenhower's Parallel Track

Eisenhower’s Parallel Track Reassessing President Eisenhower’s activism through an analysis of the development of the first US space policy A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Mark Shanahan, Department of Politics and History, Brunel University London September 2014 i Abstract: Historians of the early space age have established a norm whereby President Eisenhower's actions are judged solely as a response to the launch of the Sputnik satellite, and are indicative of a passive, negative presidency. His low-key actions are seen merely as a prelude to the US triumph in space in the 1960s. This study presents an alternative view showing that Eisenhower’s space policy was not a reaction to the heavily-propagandised Soviet satellite launches, or even the effect they caused in the US political and military elites, but the continuation of a strategic track. In so doing, it also contributes to the reassessment of the wider Eisenhower presidency. Having assessed the development of three intersecting discourses: Eisenhower as president; the genesis of the US space programme; and developments in Cold War US reconnaissance, this thesis charts Eisenhower’s influence both on the ICBM and reconnaissance programmes and his support for a non-military approach to the International Geophysical Year. These actions provided the basis for his space policy for the remainder of his presidency. The following chapters show that Sputnik had no impact on the policies already in place and highlight Eisenhower’s pragmatic activism in enabling the implementation of these policies by a carefully-chosen group of expert ‘helping hands’. -

“Iwas at My Ranch in Texas,” Lyndon Baines Johnson Recalled

CHAPTER 1: October 1957 “I was at my ranch in Texas,” Lyndon Baines Johnson recalled, “when news of Sputnik flashed across the globe . and simultaneously a new era of history dawned over the world.” Only a few months earlier, in a speech delivered on June 8, Senator Johnson had declared that an intercontinental ballistic missile with a hydrogen warhead was just over the horizon. “It is no longer the disorderly dream of some science fiction writer. We must assume that our country will have no monopoly on this weapon. The Soviets have not matched our achievements in democracy and prosperity; but they have kept pace with us in building the tools of destruction.” 1 But those were only words, and Sputnik was a new reality. Shock, disbelief, denial, and some real consternation became epidemic. The impact of the successful launching of the Soviet satellite on October 4, 1957, on the American psyche was not dissimilar to the news of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Happily, the conse- quences of Sputnik were peaceable, but no less far-reaching. The United States had lost the lead in science and technology, its world leadership and preeminence had been brought into question, and even national security appeared to be in jeopardy. “This is a grim business,” Walter Lippman said, not because “the Soviets have such a lead in the armaments business that we may soon be at their mercy,” but rather because American society was at a moment of crisis and decision. If it lost “the momentum of its own progress, it will deteriorate and decline, lacking purpose and losing confidence in itself.” 2 According to the U.S. -

Sputnik Reevaluated: Pedagogic Debate in Connecticut Secondary

Sputnik Reevaluated: Pedagogic Debate in Connecticut Secondary Schools, 1956-1964 Honors Research Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation “with Honors Research Distinction in History” in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by William J Swanek The Ohio State University August 2012 Project Advisor: Professor Steven Conn, Department of History Swanek 1 Introduction In October of 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I and the Space Race that would, in large part, function as the scorekeeper of the Cold War. The first artificial satellite to be launched into earth’s orbit ignited apprehension, doubt, and anger throughout an American society conditioned to fear and distrust the Soviets as a result of propaganda efforts within the United States. One of the most significant areas targeted for reappraisal and reform in the aftermath of the Sputnik launch was the American public school. The satellite launch signaled to many Americans that their public schools had failed in producing the technical minds required to win the Cold War. The Sputnik launch was the discrete impetus for reform efforts directed at the American high school. In the August 1st, 1958 of Congressional Digest, it was reported that the “intensity and reappraisal” of US schools was undertaken because of the Sputnik launch the previous November.1 As John L. Rudolph argues in his book Scientists in the Classroom: The Cold War Reconstruction of American Science Education, the American citizenry were frightened, demoralized, and eventually stirred to action by the launch of Sputnik.2 In Connecticut, the Hartford Courant published an editorial warning of a dangerous overreaction to the launch in Washington and the public sphere in general.3 The United States Commissioner of Education, Lawrence G. -

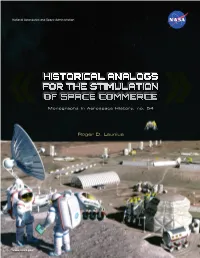

Historical Analogs for the Stimulation of Space Commerce

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Farewell from all your NASA colleagues HISTORICAL ANALOGS FOR THE STIMULATION OF SPACE COMMERCE Monographs in Aerospace History, no. 54 Roger D. Launius www.nasa.gov HISTORICAL ANALOGS FOR THE STIMULATION OF SPACE COMMERCE Roger D. Launius Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Launius, Roger D. Historical analogs for the stimulation of space commerce / Roger D. Launius. pages cm. -- (The NASA history series) (NASA SP ; 2014-4554) Summary: “The study investigates and analyzes historical episodes in America where the federal government undertook public-private efforts to complete critical activities valued for their public good and applies the lessons learned to commercial space activities”--Provided by publisher. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Space industrialization--United States. 2. Space industrialization--Government policy--United States. 3. United States--Commerce. 4. Public-private sector cooperation--United States--Case studies. 5. Public works--United States--Finance--Case studies. 6. Common good--Economic aspects--United States--Case studies. I. Title. HD9711.75.U62L28 2014 338.4’7629410973--dc23 2014013228 ISBN 978-1-62683-018-9 90000 9 781626 830189 ii HISTORICAL ANALOGS FOR THE STIMULATION OF SPACE COMMERCE Monographs in Aerospace History, no. 54 Roger D. Launius National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications Public Outreach Division History Program Office Washington, DC 2014 SP-2014-4554 iii . Table of Contents Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................vi