Some Thoughts on Caspian Terns in New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Living (Abiotic) Elements Shape Habitat

Forest Birds Fast Facts LIGHT: Dominated by tall trees, layered canopy = very shady, openings made from a fallen tree provide sunny areas AIR: Trees slow wind, except along forest edges and openings. Shade = cool temps WATER: Fog and rain collect in tree branches and drip to ground. SOIL: Lots of organics (needles, decaying leaves, tree trunks) makes lots of space for air and water. Soil absorbs and holds water like a sponge. Varied Thrush • Slender bill good at gleaning soft foods like insects, pillbugs, snails, worms, fruits and some seeds from ground. • Hops and pauses to look for food. Flips leaves and debris with bill. • Perching feet – three toes forward, hind toe back. • Can sing 2 separate notes at same time and breathe while singing. Common Raven Varied Thrush • Versatile beak. Eats everything from carrion and garbage, to eggs, nestlings, insects, seeds, rodents and fruit. • Strong, sturdy feet and grasping toes to manipulate food and perch. • Acrobatic flight, hops on ground. Uses sight to find food. Northern Flicker • The toes are placed two forward, two back to grip firmly, while the tail feathers are stiff and pointed to help brace while pounding. • Bill is shaped like a chisel. Flickers don’t excavate as much as other types of woodpeckers so have a slightly curved bill and less sharp. Common Raven • Flickers eat insects and are especially fond of ants (flickers will forage on the ground as well as on trees). Probe and explore crevices. • Distinctive flight – flap, dip, flap, dip • Woodpeckers have long, sticky and barbed tongues to extract bugs. -

Caspian Tern Nesting in South Carolina

CASPIAN TERN NESTING IN SOUTH CAROLINA TRAVIS H. McDANIEL and THEODORE A. BECKETT III Although the Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia) is known to be a year-round resident of South Carolina, the 1970 edition of South Carolina Bird Life (p. 608) lists it as a non-breeding species because no nest or eggs have been collected in the state. E. Milby Burton, T.A. Beckett III, and others who have studied the colonial birds breeding on the islands along the coast of South Carolina during the past 50 years have never found a Caspian Tern nest or chick. Wayne's statement that the species nests in the Royal Tern colonies at Cape Romain (Birds of South Carolina, 1910, p. 4) has been widely accepted, though in retrospect it appears to have been based upon questionable information received from others rather than upon field work actually conducted by the distinguished ornithologist of Oakland Plantation near Mt. Pleasant. On 5 June 1970 Travis H. McDaniel, then manager at Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge, made a routine check of nesting birds on Cape Island. As he walked through a Black Skimmer and Gull-billed Tern colony at the south end of the island, he noticed two tern eggs that were appreciably larger than those normally laid by Royal Terns, which are common nesters. During three years at Cape Romain, he had noted that Royal Terns usually lay only one egg. As McDaniel returned to his patrol truck, the birds began to settle back on their eggs. At this time he saw a very large tern dropping down from the air to settle on a nest despite harassing by Black Skimmers. -

Site Fidelity and Colony Dynaimcs of Caspian Terns Nesting at East

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Stefanie Collar for the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife Science presented on December 12, 2013. Title: Site Fidelity and Colony Dynamics of Caspian Terns Nesting at East Sand Island, Columbia River Estuary, Oregon, USA. Abstract approved: ____________________________________________________________________ Daniel D. Roby Fidelity to breeding sites in colonial birds is an adaptive trait thought to have evolved to enhance reproductive success by reducing search time for breeding habitat, allowing earlier nest initiation, facilitating mate retention, and reducing uncertainty of predator presence and food availability. Studying a seabird that has evolved relatively low colony fidelity, such as the Caspian tern, allowed me to explore the influence of stable nesting habitat on fidelity and nest site selection. The Caspian tern (Hydroprogne caspia) breeding colony on East Sand Island (ESI) in the Columbia River estuary is the largest colony of its kind in the world. This colony has experienced a decade of declining nesting success, culminating with the failure of the colony to produce any young in 2011. The objective of my study was to understand the dynamics of this Caspian tern super-colony by investigating the actions of breeding individuals over two seasons, as well as the behavior of the colony as a whole from 2001-2011. I was interested in (1) the degree of nest site fidelity exhibited by breeding terns in successive years and its relationship to reproductive success, and (2) how the interaction of top-down and bottom-up forces influenced average nesting success across the entire colony, and caused the observed trends in nesting success at the East Sand Island colony from 2001 to 2011. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Pacific Seabirds

PACIFIC SEABIRDS A Publication of the Pacific Seabird Group Volume 36 Number 2 Fall 2009 PACIFIC SEABIRD GROUP Dedicated to the Study and Conservation of Pacific Seabirds and Their Environment The Pacific Seabird Group (PSG) was formed in 1972 due to the need for better communication among Pacific seabird researchers. PSG provides a forum for the research activities of its members, promotes the conservation of seabirds, and informs members and the public of issues relating to Pacific Ocean seabirds and their environment. PSG members include research scientists, conservation professionals, and members of the public from all parts of the Pacific Ocean. The group also welcomes seabird professionals and enthusiasts in other parts of the world. PSG holds annual meetings at which scientific papers and symposia are presented; abstracts for meetings are published on our web site. The group is active in promoting conservation of seabirds, include seabird/fisheries interactions, monitoring of seabird populations, seabird restoration following oil spills, establishment of seabird sanctuaries, and endangered species. Policy statements are issued on conservation issues of critical importance. PSG’s journals are Pacific Seabirds (formerly the PSG Bulletin) and Marine Ornithology. Other publications include symposium volumes and technical reports; these are listed near the back of this issue. PSG is a member of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Ornithological Council, and the American Bird Conservancy. Annual dues for membership are $30 (individual and family); $24 (student, undergraduate and graduate); and $900 (Life Membership, payable in five $180 installments). Dues are payable to the Treasurer; see the PSG web site, or the Membership Order Form next to inside back cover. -

Hydroprogne Caspia

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation Evaluation of Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia) and Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus nivosus) Nesting on Modified Islands at the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, California—2016 Annual Report Open-File Report 2017–1055 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photograph showing Caspian tern (Hydroprogne caspia) chicks and decoy on an enhanced island in Pond SF2 of the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, California. Photograph by Crystal Shore, U.S. Geological Survey, May 11, 2016. Evaluation of Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia) and Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus nivosus) Nesting on Modified Islands at the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, California— 2016 Annual Report By C. Alex Hartman, Joshua T. Ackerman, Mark P. Herzog, Cheryl Strong, David Trachtenbarg, and Crystal A. Shore Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation Open-File Report 2017–1055 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William H. Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https:/store.usgs.gov. -

OFO Ontb-Dec210-W Review.Qxp

Successful renesting of Caspian Terns on Mohawk Island, Lake Erie, after complete colony failure Laura E. King and Shane R. de Solla The Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia, island previously provided breeding habi- formerly Sterna caspia) is the world's tat for Common Terns (Sterna hirundo) largest tern and nests globally in dense but their last reported nesting was in 2004 colonies in and around bodies of water. In (Morris 2010), although the species has Ontario, on the Great Lakes, they nest been sighted in 2009 and 2010 flying near regularly on Lakes Huron, Ontario, and the island. Other waterbirds and passer- Erie, generally on islands, peninsulas, or ines (various species of ducks, swallows, protected beaches. Caspian Terns nest on etc.) are sighted on and around the island sand, gravel, or limestone substrates with regularly. little or no vegetation (Ludwig 1965, During the course of our research on Quinn and Sirdevan 1998). At Mohawk Double-crested Cormorants, we visited Island (also known as Gull Island), in east- Mohawk Island several times during the ern Lake Erie between the communities of summers of 2009 and 2010. On 6 June Port Maitland and Lowbanks, a colony 2010, a large seiche (a standing wave in a nests on a beach consisting almost exclu- closed body of water such as a lake) caused sively of crushed Dreissenid (zebra and a nearly one metre rise in water levels in quagga) mussel shells. The earliest record- eastern Lake Erie (Figure 1). Lake Erie is ed colony on Mohawk was 80 pairs in prone to large seiches because of its loca- 1996 (Morris 2010) and since then the tion, shape, and shallow western basin colony has fluctuated between 165 and (NOAA 2003, Litchkoppler 2009). -

Life History Account for Caspian Tern

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group CASPIAN TERN Hydroprogne caspia Family: LARIDAE Order: CHARADRIIFORMES Class: AVES B227 Written by: M. Rigney, S. Granholm Reviewed by: H. Cogswell Edited by: R. Duke DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY Common to very common along the California coast and at scattered locations inland, from April through early August. Nests in dense colonies on sandy estuarine shores, on levees in salt ponds, and on islands in alkali and freshwater lakes (Small 1974, Cogswell 1977). Breeding adult often flies substantial distances to forage in lacustrine, riverine, and fresh and saline emergent wetland habitats (Gill 1976). Nesting colonies are located at south San Francisco Bay, San Diego Bay, and several lakes in Modoc and Lassen cos. (Cogswell 1977, Garrett and Dunn 1981). Small colonies recently reported on Humboldt Bay, San Pablo Bay, and Elkhorn Slough, Monterey Co. (Gill and Mewaldt 1983). An analysis of banding recoveries indicates a shifting from nesting in numerous small colonies associated with freshwater marshes in interior California, to nesting in large colonies on human-created habitats along the coast (Gill and Mewaldt 1983). Large numbers are present at the Salton Sea in the breeding season, but nesting no longer occurs there. This species winters from southern California, where it is locally fairly common, south to Central and South America. Scattered individuals have been noted in winter along the central and northern California coast. SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Feeds primarily on small fish in freshwater lakes, estuaries, and salt ponds. Sometimes feeds over the open ocean, near shore (Cogswell 1977). -

Caspian Tern Hydroprogne Caspia

Wyoming Species Account Caspian Tern Hydroprogne caspia REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: Migratory Bird USFS R2: No special status USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Protected Bird CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: No special status WGFD: NSS3 (Bb), Tier II WYNDD: G5, S1 Wyoming Contribution: MEDIUM IUCN: Least Concern PIF Continental Concern Score: Not ranked STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia) has no additional regulatory status or conservation rank considerations beyond those listed above. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: Following the reclassification of the genus Sterna in 2006, Caspian Tern (formerly S. caspia) was moved to the genus Hydroprogne 1. Although American and Australian subspecies have been suggested, there are currently no formally recognized subspecies of Caspian Tern 2, 3. Description: Identification of Caspian Tern is possible in the field. It is the largest species of tern; adults weigh between 530–782 g, range in length from 47–54 cm, and have a wingspan of approximately 127 cm 2, 4. The sexes are similar in size and appearance 2. Caspian Tern has a slightly crested crown and a dark cap that extends below the eye (solid black in the breeding season and mottled dark gray in the non-breeding season), white underbody, pale gray wings, primaries that are dark on the underside, a short slightly notched tail, dark eyes, thick red bill with a dark grey tip that fades to a pale orange or red at the extreme tip, and black legs and feet 2, 4. Two other species of tern are known to breed in Wyoming: Black Tern (Chlidonias niger) and Forster’s Tern (S. -

HELCOM Red List

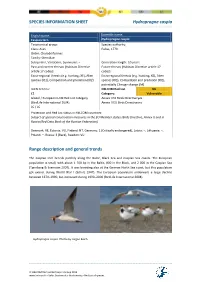

SPECIES INFORMATION SHEET Hydroprogne caspia English name: Scientific name: Caspian tern Hydroprogne caspia Taxonomical group: Species authority: Class: Aves Pallas, 1770 Order: Charadriiformes Family: Sternidae Subspecies, Variations, Synonyms: – Generation length: 10 years Past and current threats (Habitats Directive Future threats (Habitats Directive article 17 article 17 codes): codes): Extra-regional threats (e.g. hunting; XE), Alien Extra-regional threats (e.g. hunting; XE), Alien species (I01), Competition and predation (I02) species (I01), Competition and predation (I02), potentially Climage change (M) IUCN Criteria: HELCOM Red List VU C1 Category: Vulnerable Global / European IUCN Red List Category Annex I EU Birds Directive:yes (BirdLife International 2004) Annex II EU Birds Directive:no LC / LC Protection and Red List status in HELCOM countries: Subject of special conservation measures in the EU Member states (Birds Directive, Annex I) and in Russia (Red Data Book of the Russian Federation) Denmark: RE, Estonia: VU, Finland: NT, Germany: 1 (Critically endangered), Latvia: –, Lithuania: –, Poland: –, Russia: 3 (Rare), Sweden: VU Range description and general trends The Caspian tern breeds patchily along the Baltic, Black Sea and Caspian Sea coasts. The European population is small, with about 1 700 bp in the Baltic, 800 in the Black, and 2 000 in the Caspian Sea (Tjernberg & Svensson 2007). It was breeding also at the German North Sea coast, but this population got extinct during World War I (Schulz 1947). The European population underwent a large decline between 1970–1990, but increased during 1990–2000 (BirdLife International 2004). Hydroprogne caspia. Photos by Jürgen Reich. © HELCOM Red List Bird Expert Group 2013 www.helcom.fi > Baltic Sea trends > Biodiversity > Red List of species SPECIES INFORMATION SHEET Hydroprogne caspia Distribution and status in the Baltic Sea region The Baltic breeding population increased from 500 bp in the mid–1930s to 1 200 bp in 1953 and finally to 2,500 bp in 1971, an undisputed peak so far. -

Mongolia (Tour Participant Martin Hale)

Pallas’s Sandgrouse epitomise the wilds of Mongolia (tour participant Martin Hale) MONGOLIA 21 MAY – 4/8 JUNE 2016 LEADERS: MARK VAN BEIRS and TERBISH KHAYANKHAYRVAA The enormous, landlocked country of Mongolia is the 19th largest and the most sparsely populated fully sovereign country in the world. At 1,564,116 km² (603,909 sq mi), Mongolia is larger than the combined areas of Germany, France and Spain and holds only three million people. It is one of our classic eastern Palearctic destinations and travelling through Mongolia is a fantastic experience as the scenery is some of the best in the world. Camping is the only way to discover the real Mongolia, as there are no hotels or ger camps away from the well-known tourist haunts. On our 19 day, 3,200km off-road odyssey we wandered through the wide and wild steppes, deserts, semi-deserts, mountains, marshes and taiga of Genghis Khan’s country. The unfamiliar feeling of ‘space’ charged our batteries and we experienced both icy cold and rather hot weather. Mongolia does not yield a long birdlist, but it holds a fabulous array of attractive specialities, including many species that are only known as vagrants to Europe and North America. Spring migration was in full swing with various Siberia-bound migrants encountered at wetlands and migrant hotspots. The 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Mongolia www.birdquest-tours.com endearing Oriental Plover was the Bird of the Trip as we witnessed its heart-warming flight display several times at close range. The magnificent eye-ball to eye-ball encounter with an angry Ural Owl in the Terelj taiga will never be forgotten and we also much enjoyed the outstanding experience of observing a male Hodgson’s Bushchat in his inhospitable mountain tundra habitat. -

Biology and Structure of the Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne

BIRD-BANDING A JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION VOL. XXXVI OCTOBER,1965 NO. 4 BIOLOGY AND STRUCTURE OF THE CASPIAN TERN (HYDROPROGNE CASPIA) POPULATION OF THE GREAT LAKES FROM 1896- 1964 By JAMESPINSON LUDWIG A population of the cosmopolitan Caspian Tern (Hy&'oprogne caspia) breeds on islands in the Great Lakes of North Anierica. First report of this population came from Cass who collected eggs at Shoe Island in 1896, and Reed found a colony at Hat Island in 1904 (Barrows, 1912). All coloniesin this population (except Chari- ty Islands' Reef) are in northern Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, falling in a rectangle bounded by 080020', 087040', 46010', and 45020' . Since 1896, thirteen colonieshave been found, ten of them active in 1964. Bmxding was begun in 1922 at Shoe Island, 1924 at Gravelly Island, and 1927 at South Limestone Island, and con- tinued through 1964. This paper deals primarily with an analysis of 370 recoveriesof Caspiansbanded as chicks in the Great Lakes' colonies. F. E. Lud- wig (1942) and Hickey (1952) each analyzed a part of the recoveries used in this paper. Data gathered between 1959 and 1964 on popu- lar.ion size, nesting, food habits, and endoparasites are also pre- sented. Data on population and nesting were gathered by counting nests,dead chicks, etc., or by standard censusprocedures. NESTING Although Bent (1921) states that the Caspian Tern "nests under widely different conditions", I found coloniesonly on islands with sand-gravel or limestone substrateswhich had sparse or no vegeta- tion. Ordinarily the nest is a simple unlined hollow in the gravel, but it may be thinly lined by grasses.