Four Lonely Souls Staring at the Sky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Afghanistan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 2 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 3 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 24 Culture Gram .......................................................... 30 Kazakhstan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 39 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 40 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 58 Culture Gram .......................................................... 62 Uzbekistan ................................................................. CIA Summary ......................................................... 67 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 68 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 86 Culture Gram .......................................................... 89 Tajikistan .................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 99 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 117 Culture Gram .......................................................... 121 AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT ECONOMY Chief of State Economic Overview President of the Islamic Republic of recovering -

EL PATO: DE JUEGO SOCIAL a DEPORTE DE ELITE Mer

Recorde: Revista de História do Esporte Artigo volume 1, número 1, junho de 2008 Stela Ferrarese EL PATO: DE JUEGO SOCIAL A DEPORTE DE ELITE Mer. Stela Maris Ferrarese Capettini Universidad Nacional del Comahue Neuquen, Argentina [email protected] Recebido em 28 de janeiro de 2008 Aprovado em 13de março de 2008 Resumen El pato es un juego ancestral argentino practicado con caballos y un pato. El mismo fue incorporado por los gauchos y rechazado por la oligarquía. Actualmente luego de ser convertido en deporte por Rosas, prohibido y recuperado por Perón como deporte nacional esa misma oligarquía se lo apropió y practica como deporte de competición. En otros lugares del país, alejados de la “industria del deporte” se sigue enseñando y practicando entre la “otra parte de la sociedad nacional”. Palabras claves: juego ancestral; deporte; antropologia lúdica. Resumo O pato: de jogo social a um esporte de elite O Pato é um jogo ancestral argentino praticado com cavalos e um pato. O mesmo foi incorporado pelos gaúchos e rejeitado pela oligarquia. Atualmente, após ser convertido em esporte por Rosas, proibido e recuperado por Perón como esporte nacional, essa mesma oligarquia se apropriou dele e o pratica como esporte de competição. Em outros lugares do país, desprovidos da “indústria do esporte”, continua sendo treinado e praticado entre a “outra parte da sociedade nacional”. Palavras-chave: jogo ancestral; esporte; antropologia lúdica. Abstract El pato: from a social game to an elite sport The pato is an ancestral Argentinean game practiced with horses and a duck. The same one which was incorporated by the gauchos and rejected by the oligarchy. -

From People to Entities

From People to Entities: Typed Search in the Enterprise and the Web Der Fakultat¨ fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informatik der Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universitat¨ Hannover zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) genehmigte Dissertation von MSc Gianluca Demartini geboren am 06.12.1981, in Gorizia, Italien. 2011 Referent: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Nejdl Ko-Referent: Prof. Dr. Heribert Vollmer Ko-Referent: Prof. Dr. Arjen P. de Vries Tag der Promotion: 06. April 2011 ABSTRACT The exponential growth of digital information available in Enterprises and on the Web creates the need for search tools that can respond to the most sophisticated informational needs. Retrieving relevant documents is not enough anymore and finding entities rather than just textual resources provides great support to the final user both on the Web and in Enterprises. Many user tasks would be simplified if Search Engines would support typed search, and return entities instead of just Web pages. For example, an executive who tries to solve a problem needs to find people in the company who are knowledgeable about a certain topic. Aggregation of information spread over different documents is a key aspect in this process. Finding experts is a problem mostly considered in the Enterprise setting where teams for new projects need to be built and problems need to be solved by the right persons. In the first part of the thesis, we propose a model for expert finding based on the well consolidated vector space model for Information Retrieval and investigate its effectiveness. We can define Entity Retrieval by generalizing the expert finding problem to any entity. -

140720Sun.15E.Pdf

Page 7 • The Morning Line • Sunday, July 20, 2014 2014 P OLO S EA S ON THEMORNINGLINE Sunday, July 20, 2014 WWW.THEMORNINGLINE.COM Where’s Polo Today? POLOEditor & Publisher: Frederic Roy • phone: 561 315 3111 • [email protected] • © 2014 Trophy Inc. all rights reserved THIS PAST WEEK’S WINNERS PAGE 7 PAGE 10 PAGE 14 VEUVE CLICQUOT GOLD PAGE 13 CUP FINAL TODAY Page 2 • The Morning Line • Sunday, July 20, 2014 VEUVE CLICQUOT GOLD CUP SCHEDULE & RESULTS ML Polo Update - Sunday, July 20, 2014 - AM Cowdray Park Polo Club, U.K. June 24-July 20, 2014 - 14 teams - 22 goal Polo at Glance Quarterfinals Rashid Albwardy 2 Bridgehampton. 16-8 win for White Birch over KIG yesterday on opening day at DUBAI Alastair Paterson 3 Bridgehampton for the Monty Waterbury Cup. Next game is Wednesday at 5pm Adolfo Cambiaso 10 Equuleus vs C.T - Energia, to be played at Equuleus. Diego Cavanagh 7 DUBAI 22 Greenwich, The East Coast Open. Final rescheduled for Monday 21st at 3pm in Maitha Al Maktoum 0 Game 1 UAE Sunday 13 Greenwich. The subisdiary is this afternoon Sunday 20 at 4pm. Lucas Monteverde 8 Def. UAE 11-10 Pablo MacDonough 10 DUBAI Ollie Cudmore 4 Subsidiary final, Sunday, July 20, 4pm 22 Semifinal Airstream 20 // 1-2 Facundo Pieres 10 Wed July 16 Peter Orthwein 1 Lyndon Lea 1 ZACARA Def. Halcyon Guille Aguero 6 Gonzalo Deltour 7 Gallery 9-8 Michel Dorignac 6 Matt Perry 4 HALCYON GALLERY Mariano Gonzalez 7 22 vs. Game 4 George Hanbury 3 CT Energia 19 // 1-2 HALCYON GALLERY Sun 13 Mark Tomlinson 6 Def. -

2006 Texas Reading Club Manual

2006 Texas Reading Club Manual Written By: Claire Abraham, Waynetta Asmus, Debra Breithaupt, Teresa Chiv, Catherine Clyde, Alexandra Corona, Kippy Edge, Paula Gonzales, Tina Hager, Jeanette Larson, Jaye McLaughlin, Susan Muñoz, Vonnie Powell Clip Art By: Frank Remkiewicz Theme Songs By: Sara Hickman and Sally Meyers Craft Patterns and Illustrations By: Shawn Clements Edited By: Jeanette Larson and Christine McNew Published By: The Library Development Division of the Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin, Texas 2006 2 Reading: The Sport of Champions! Texas Reading Club Manual 3 Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................. 6 Artist, Authors, and Songwriters ........................................................................................ 7 Something About the Artist, Frank Remkiewicz Acceptable Use of Artwork Something About the Authors and Songwriters Introduction....................................................................................................................... 12 Goals and Purpose Using This Manual Clip Art Theme Songs A Note About Web Sites Library Outreach Research Related to Summer Reading Every Child Ready to Read @ Your Library Legalities: The Bingo Enabling Act, Copyright Issues, Music, Films Serving Children with Disabilities Marketing, Cooperation, and PR Suppliers for Incentives, Crafts, and Program Materials Theme Songs.................................................................................................................... -

Hoofbeatsnational Riding, Training and Horse Care Magazine

Vol 35 No 3 Oct/Nov 2013 A hoofbeatsNational Riding, Training and Horse Care Magazine . incorporating The Green Horse -sustainable horsekeeping. Inside Shoulder-In Endurance - Meg Produced by page 4 Wade’s return to HOOFBEAT PUBLICATIONS riding after a brain 90 Leslie Road, Wandi, 6167 injury. Ph: (08) 9397 0506 page 8 Fax: (08) 9397 0200 Unlocking the Locking Device - Email: the patella - Office/accounts: [email protected] page 18 Subscriptions: [email protected] Ads: [email protected] Monty Roberts - page 39 Why those Reins - Showscene: [email protected] page 28 Green Horse: [email protected] Editorial: [email protected] Emag: [email protected] How to Remove a Horse Shoe - www.hoofbeats.com.au page 24 MANAGING EDITOR Sandy Hannan EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Carol Willcocks Carole Watson Contributing Editors Wendy Elks ADVERTISING by Liz Tollarzo Tracy Weaver Sayer 4 SHOULDERIN More challenging to perfect than it appears, shoulder-in promotes a horse’s OFFICE / ACCOUNTS suppleness and obedience to the bending, forward driving, sideways pushing and Katrina Bailey restraining aids. GRAPHICS AND WEB Caitlin Bolger 8 ENDURANCE in sport and in life by Wendy Elks with Meg Wade Louise and Adrian Redman Former international endurance rider, Meg ade, is fighting her way back from a brain E-MAGAZINE injury with the same determination that took her to the top of her beloved sport. Diane Bawden SUBSCRIPTIONS 18 BRAKES or no brakes by Sandi Simons Bob Hannan The ‘stop’ and ‘go’ cues are integral to a horse’s education and the rider’s enjoyment, but if a horse has faulty brakes it’s never too late to correct them. -

2019 Tournaments

2020 UNITED STATES POLO ASSOCIATION® 2019 TOURNAMENTS U.S. OPEN POLO CHAMPIONSHIP® (18-22 Goal) International Polo Club Palm Beach - Wellington, Florida March 27 - April 21, 2019 PILOT Left to Right: Facundo Pieres, Gonzalito Pieres, Curtis Pilot, Colo Gonzalez PILOT DAILY RACING FORM LA INDIANA Curtis Pilot James “Jared” Zenni III Michael D. Bickford Matias “Colo” Gonzalez Santiago Cernadas Tomas Garcia del Rio Facundo Pieres Agustin Obregon Jeffrey Hall Gonzalo Pieres Jr. Geronimo Obregon Facundo Obregon Mia Bray Bautista Ortiz de Urbina EQUULEUS ASPEN LAS MONJITAS Joseph DiMenna Camilo Bautista Stewart Armstrong Mariano Gonzalez Sr. Lucas James Matthew Coppola Christian “Magoo” Laprida Jr. Francisco Elizalde Pablo “Polito” Pieres Jr. Ignacio “Inaki” Laprida Tomas Schwencke Hilario Ulloa Milo Dorignac CESSNA OLD HICKORY BOURBON Edward “Chip” Campbell III ICONICA Stephen Orthwein Jr. Felipe “Pipe” Marquez Maureen Brennan Jason Crowder Ezequiel Martinez Ferrario Mariano “Peke” Gonzalez Jr. Will Johnston Felipe Viana Matias Magrini Miguel Novillo Astrada Eduardo Novillo Astrada Sebastian Merlos Stuart “Sugar” Erskine Raul “Gringo” Colombres PARK PLACE COCA-COLA Juan Cruz Merlos Gillian Johnston Andrey Borodin Ignatius du Plessis Juan Britos Julian de Lussaretta Cody Ellis Steven Krueger Tomas Collingwood Ignacio Novillo Astrada Nicolas Pieres Lucas Diaz Alberdi 184 UNITED STATES POLO ASSOCIATION® 2020 POSTAGE STAMP FARM SD FARMS TONKAWA Annabelle Gundlach Sayyu Dantata Jeffrey Hildebrand Mariano Aguerre Jesus “Pelon” Escapite Jr. Guillermo “Sapo” Caset Jr. Joaquin Panelo Cesar “Peco” Polledo Christian “Sterling” Giannico Valerio “Lerin” Zubiaurre Juan “Tito” Ruiz Guinazu Agustin “Tincho” Merlos Constancio “Costi” Caset Tim J. Dutta Malia Bryan Joaquin Pittaluga Leon Schwencke STABLE DOOR POLO Henry Porter SANTA CLARA Santino Magrini Luis Escobar Victorino “Torito” Ruiz Jorba Nicolas Escobar Santiago Toccalino Mariano “Nino” Obregon Jr. -

Para Leer Al Pato Donald Comunicación De Masa Y Colonialismo

Para leer al Pato Donald Comunicación de masa y colonialismo Ariel Dorfman y Armand Mattelart La Caja de Herramientas archivo.juventudes.org Ariel Dorfman y Armand Matelart, Para leer al Pato Donald. ÍNDICE DONALD Y LA POLÍTICA ....................................................................... 3 PRO-LOGO PARA PATO-LOGOS ........................................................... 7 INTRODUCCIÓN ...................................................................................... 8 I. TÍO, CÓMPRAME UN PROFILÁCTICO ........................................... 15 II. DEL NIÑO AL BUEN SALVAJE .......................................................... 27 III. DEL BUEN SALVAJE AL SUBDESARROLLADO .......................... 36 IV. EL GRAN PARACAIDISTA ................................................................ 54 V. LA MAQUINA DE LAS IDEAS ............................................................ 61 VI. EL TIEMPO DE LAS ESTATUAS MUERTAS .................................. 74 CONCLUSIÓN: ¿EL PATO DONALD AL PODER? ............................... 91 ANEXO: NÚMEROS DE LAS REVISTAS ANALIZADAS .................... 97 NOTAS......................................................................................................... 98 Digitalización partiendo de la 21ª edición de la Editorial Siglo XXI (empleando un archivo escaneado hallado en Internet cuya autoría desconocemos). Los términos a los que se refieren las notas de la página 98 están señalados con un asterisco [*] 2 Ariel Dorfman y Armand Matelart, Para leer al Pato Donald. DONALD -

Argentina-Report-World

CultureGramsTM World Edition 2015 Argentina (Argentine Republic) Before the Spanish began to colonize Argentina in the 1500s, BACKGROUND the area was populated by indigenous groups, some of whom belonged to the Incan Empire. However, most groups were Land and Climate nomadic or autonomous. Colonization began slowly, but in Argentina is the-eighth largest country in the world; it is the 1700s the Spanish became well established and somewhat smaller than India and about four times as big as indigenous peoples became increasingly marginalized. The the U.S. state of Texas. Its name comes from the Latin word British tried to capture Buenos Aires in 1806 but were argentum, which means “silver.” Laced with rivers, Argentina defeated. The British attempt to conquer the land, coupled is a large plain rising from the Atlantic Ocean, in the east, to with friction with Spain, led to calls for independence. At the the towering Andes Mountains, in the west, along the Chilean time, the colony included Paraguay and Uruguay as well as border. The Chaco region in the northeast is dry, except Argentina. during the summer rainy season. Las Pampas, the central Independence plains, are famous for wheat and cattle production. Patagonia, A revolution erupted in 1810 and lasted six years before to the south, consists of lakes and rolling hills and is known independence was finally declared. Those favoring a centrist for its sheep. The nation has a varied landscape, containing government based in Buenos Aires then fought with those such wonders as the Iguazú Falls (1.5 times higher than who favored a federal form of government. -

I / 2014, Volume 3• No 5

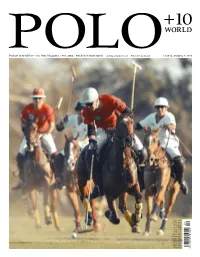

world polo+10 world – The polo Magazine • Est. 2004 • published worldwide www.poloplus10.com printed in Germany I / 2014, Volume 3• No 5 75,00 AEd 130,00 ArS 22,00 AUd 7,60 BHd 18,60 CHF 123,80 CNY 15,00 EUr 12,70 GBp 158,00 HKd 1.280,00 INr 2.050,00 JpY 75,00 QAr 670,00 rUB 25,20 SGd 20,50 USd 215,00 ZAr editorial polo +10 world 3 POLO+10 Jubilee the first edition of POLO+10 was published in spring 2004. ten years during which the sport has developed at an astonishing rate. As was the case last year, POLO+10 is once again present at the most important tourna- ment in the polo world – the Palermo Open. The feedback from Argentina was overwhel- mingly positive last year and reassured that we want to offer a communicative platform for the polo community that also comprises international editions, not just those that focus on European regions. But this is just one aspect of our current plans. Plenty of new countries are just starting to embark on their polo careers, including Kazakhstan and Monaco, and we have devoted some space in this edition to highlighting these countries. We published the first edition of our POLO+10 magazine at the start of 2004. Back then, we confronted some doubt as some in Germany and Europe did not consider the sport important enough for it to have its own publication. Ten years later, we are all better informed – including the naysayers. For our tenth anniversary, we would like to thank you for your generous support, friendly communication and your many new visions about the sport! POLO+10 has made friends and partners across the world and follows the sport from an unrivalled international perspective. -

Background Material

THE ENABLING ENVIRONMENT CONFERENCE Effective Private Sector Contribution to Development in Afghanistan UNLEASHING ENTREPRENEURSHIP: NURTURING AN ENABLING ENVIRONMENT FOR SME DEVELOPMENT IN AFGHANISTAN Background paper prepared for the Enabling Environment Conference by: UNDP Afghanistan I. INTRODUCTION natural partners for a step-by-step approach to economic development. Promoting a favourable In his message to the international conference climate for SMEs to thrive is therefore key to the “Afghanistan and the International Community - A successful and lasting economic development of Partnership for the Future”, held in Berlin from 31 Afghanistan. March to 1 April 2004, President Karzai averred the commitment “to create the enabling environment In view of the importance of SMEs, this paper for both the domestic private sector, including the focuses on the impediments which SMEs face, and Afghan diaspora, and the international private proposes ways to tackle them (many of which are sector to thrive in our country”. This commitment already in progress). It follows the blueprint set out has been reiterated in a series of national strategy in UNDP’s Unleashing Entrepreneurship 2004 documents – especially in Afghanistan’s National report and concentrates on ways to create an Development Strategy (ANDS) of 2005 – and is enabling environment for private sector being implemented at different levels of development (PSD) in general, and SME government in various sectors of production. development in particular – a process which was identified as crucial by numerous private and public Whatever their persuasions, governments sector stakeholders across the country. frequently view small and medium enterprises (SMEs) as critical to private sector development, as The paper’s arguments and recommendations focus they can help economies attain more broad-based on a set of five issues identified as central to the uniform growth, and help encourage an successful promotion of SME development in entrepreneurial mentality in the business sector. -

Australian Polo Summer Series 2010 Programme Series 2 Contents Page

AUSTRALIAN POLO SUMMER SERIES 2010 PROGRAMME SERIES 2 CONTENTS PAGE Welcome 2 The “need to know” about polo 4 Chief Umpire 6 Directions to polo facilities 6 Tournament teams 7 Tournament play days 7 Polo rules for the spectator 14 Penalties, fouls and crossing 15 Things to do in Sydney and surrounds 16 The New 2010 Range Rover Vogue Most Advanced, Most Powerful and Most Complete luxury all-terrain vehicle. Available Now at Alto Land Rover 13 GOAL FEBRUARY 2010 SYDNEY 1 WELCOME FEBBRAIO 2010 DOM LUN MAR MER GIO VEN SAB 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Dear Polo Supporter, Polo is not possible without support from its major contributors, 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 to this end we are privileged to receive the support of some of 28 Welcome to the inaugural Australian Polo Summer Series (“APSS”) Australia’s oldest and most respected high goal polo operations to be held throughout the month of February on some of the best namely, Ellerston Polo (Packer Family) and Jemalong Polo polo fields the Sydney region has to offer and surely amongst some (Kahlbetzer Family), as well as support from some of the more of the best overall facilities on offer in the southern hemisphere. recently established professional operations including Sydney Polo The aim of the APSS is to bring to the Australian polo scene a (Higgins Family) and Yindarra Polo (Private). new format, a series of higher goal rated tournaments each of Over time and with the cooperation of the Australian Polo two week duration and each to be played on specifically prepared Association we aim to extend the Summer Series format and reach grounds reserved exclusively for Summer Series games.