Just As the Declaration of Independence Had Laid out The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789 Kiley Bickford University of Maine - Main Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation Bickford, Kiley, "Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789" (2014). Honors College. 147. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/147 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONALISM IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION OF 1789 by Kiley Bickford A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for a Degree with Honors (History) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Richard Blanke, Professor of History Alexander Grab, Adelaide & Alan Bird Professor of History Angela Haas, Visiting Assistant Professor of History Raymond Pelletier, Associate Professor of French, Emeritus Chris Mares, Director of the Intensive English Institute, Honors College Copyright 2014 by Kiley Bickford All rights reserved. Abstract The French Revolution of 1789 was instrumental in the emergence and growth of modern nationalism, the idea that a state should represent, and serve the interests of, a people, or "nation," that shares a common culture and history and feels as one. But national ideas, often with their source in the otherwise cosmopolitan world of the Enlightenment, were also an important cause of the Revolution itself. The rhetoric and documents of the Revolution demonstrate the importance of national ideas. -

Populist Discourse in the French Revolution Rebecca Dudley

Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies Volume 33 Article 6 2016 Do You Hear the People Sing?: Populist Discourse in the French Revolution Rebecca Dudley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sigma Part of the European History Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dudley, Rebecca (2016) "Do You Hear the People Sing?: Populist Discourse in the French Revolution," Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies: Vol. 33 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sigma/vol33/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Do You Hear the People Sing?: Populist Discourse in the French Revolution by Rebecca Dudley The rallying cry of the French Revolutionaries was "Liberte! Egalite! Fraternite!" (liberty, equality, fraternity), and the French Revolution, a pivotal moment in French, European, and world history, has been consistently considered one of the first and most significant nationalist movements. Research and literature thus far on discourse in this revolution have focused on nationalism Qenkins 1990; Hayward 1991; O'Brien 1988), along with the discourses of violence and terror that led to the graphic revolu tion (Ozouf 1984; Leoussi 2001). The presence of nationalist discourse and nationalist sentiment in the French Revolution is undeniable, but there are other elements poten tially missing from the current analyses. -

Improving the Total Force Using National Guard and Reserves

IMPROVING THE TOTAL FORCE USING THE NATIONAL GUARD AND RESERVES A Report for the transition to the new administration by The Reserve Forces Policy Board RFPB Report FY17-01 This report, Report FY17-01, is a product of the Reserve Forces Policy Board. The Reserve Forces Policy Board is, by law, a federal advisory committee within the Office of the Secretary of Defense. As mandated by Congress, it serves as an independent adviser to provide advice and recommendations directly to the Secretary of Defense on strategies, policies, and practices designed to improve and enhance the capabilities, efficiency, and effectiveness of the reserve components. The content and recommendations contained herein do not necessarily represent the official position of the Department of Defense. As required by the Federal Advisory Committee Act of 1972, Title 5, and the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 41, Section 102-3 (Federal Advisory Committee Management), this report and its contents were deliberated and approved in several open, public sessions. IMPROVING THE TOTAL FORCE USING THE NATIONAL GUARD AND RESERVES A Report for the transition to the new administration by The Reserve Forces Policy Board RFPB Report FY17-01 4 5 6 Chairman Punaro introduces the Secretary of Defense, the Honorable Ashton B. Carter, during the June 9, 2015 Board Meeting. “The presence, skill and readiness of Citizen Warriors across the country give us the agility and flexibility to handle unexpected demands, both at home and abroad. It is an essential component of our total force, and a linchpin of our readiness.” 1 - Secretary of Defense Ash Carter 1 As Delivered by Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, Pentagon Auditorium, Aug. -

The Ohio National Guard Before the Militia Act of 1903

THE OHIO NATIONAL GUARD BEFORE THE MILITIA ACT OF 1903 A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Cyrus Moore August, 2015 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Cyrus Moore B.S., Ohio University, 2011 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Kevin J. Adams, Professor, Ph.D., Department of History Master’s Advisor Kenneth J. Bindas, Professor, Ph.D, Chair, Department of History James L Blank, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I. Republican Roots………………………………………………………19 II. A Vulnerable State……………………………………………………..35 III. Riots and Strikes………………………………………………………..64 IV. From Mobilization to Disillusionment………………………………….97 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….125 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………..136 Introduction The Ohio Militia and National Guard before 1903 The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed a profound change in the militia in the United States. Driven by the rivalry between modern warfare and militia tradition, the role as well as the ideology of the militia institution fitfully progressed beyond its seventeenth century origins. Ohio’s militia, the third largest in the country at the time, strove to modernize while preserving its relevance. Like many states in the early republic, Ohio’s militia started out as a sporadic group of reluctant citizens with little military competency. The War of the Rebellion exposed the serious flaws in the militia system, but also demonstrated why armed citizen-soldiers were necessary to the defense of the state. After the war ended, the militia struggled, but developed into a capable military organization through state-imposed reform. -

How Was the Course of the Revolution Shaped by the People of Paris From

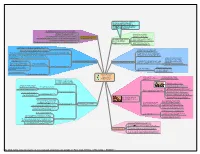

Remember the bourgeoisie were significant in directing the revolution, making up the membership of the National Assembly, the Legislative Assembly & the Convention & the peasants influenced events through their violence e.g. the Great Fear led to the August Decrees which destroyed feudalism in 1789. The Terror gradually moved beyond the Sans Culottes' control as the Committee of Public Safety became more ruthless, seeking more centralised government. Enthusiastic supporters of the Terror found themselves The power of the crowds & the Sans its next victims, e.g. the popular leader, Danton. Culottes was centred on Paris though there were some in the provinces, The revolutionary armies & the popular societies in the sections were disbanded. Why did the influence of the Sans particularly in the revolutionary armies. The law of Maximum was extended to control wages as well as food, despite continuing food shortages. Culottes' wane after 1794? The crowds & Sans Culottes were influential through The crowds & the Sans Culottes their use of Parisian journees to effect change e.g. The Thermidorian Reaction that toppled Robespierre broke their power. were one of a number of through the October Days 1795 saw the arrests of & disarmament of Sans Culottes, the closure of the Jacobin Club & the Paris Commune. influences that shaped the revolution. The Sans Culottes were dominant in the National Guard, the Parisian sections & the revolutionary commune set up in 1792. Some historians think the Terror was the work of a bloodthirsty mob of frustrated men who enjoyed their taste of power and revelled in an orgy of violence Paris was only 12 miles from Versailles so news of Other historians think the Terror was the work of sincere revolutionaries There are 2 opposing views amongst historians the latest political developments always reached trying to clear France of privilege, corruption & the enemies of revolution. -

After Robespierre

J . After Robespierre THE THERMIDORIAN REACTION Mter Robespierre THE THERMIDORIAN REACTION By ALBERT MATHIEZ Translated from the French by Catherine Alison Phillips The Universal Library GROSSET & DUNLAP NEW YORK COPYRIGHT ©1931 BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC. ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED AS La Reaction Thermidorienne COPYRIGHT 1929 BY MAX LECLERC ET CIE UNIVERSAL LIBRARY EDITION, 1965 BY ARRANGEMENT WITH ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 65·14385 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PREFACE So far as order of time is concerned, M. M athie( s study of the Thermidorian Reaction, of which the present volume is a translation, is a continuation of his history of the French Revolution, of which the English version was published in 1928. In form and character, however, there is a notable difference. In the case of the earlier work the limitations imposed by the publishers excluded all references and foot-notes, and the author had to refer the reader to his other published works for the evidence on which his conclusions were based. In the case of the present book no such limitations have been set, and M. Mathiei: has thus been able not only to state his con clusions, but to give the chain of reasoning by which they have been reached. The Thermidorian Reaction is therefore something more than a sequel to The French Revolution, which M. Mathiei:, with perhaps undue modesty, has described as a precis having no independent authority; it is not only a work of art, but a weighty contribution to historical science. In the preface to his French Revolution M. -

THE COMPLICATIONS of RESISTING REVOLUTION Michael Chrzanowski [email protected]

University of Massachusetts nU dergraduate History Journal Volume 3 Article 1 2019 ENEMIES OR SAVIORS: THE COMPLICATIONS OF RESISTING REVOLUTION Michael Chrzanowski [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umuhj Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Chrzanowski, Michael (2019) "ENEMIES OR SAVIORS: THE COMPLICATIONS OF RESISTING REVOLUTION," University of Massachusetts nU dergraduate History Journal: Vol. 3 , Article 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7275/nxx6-v711 Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umuhj/vol3/iss1/1 This Primary Source-Based Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Massachusetts ndeU rgraduate History Journal by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUMMER 2019 UNDERGRADUATEChrzanowski: ENEMIES HISTORY OR SAVIORS JOURNAL 1 ENEMIES OR SAVIORS: THE COMPLICATIONS EOFNEMIES RESISTING OR REVOLUTION SAVIORS: THE COMPLICATIONS OF RESISTING REVOLUTION MICHAEL CHRZANOWSKI MICHAEL CHRZANOWSKI Published by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst, 2019 1 SUMMER 2019 UniversityUNDERGRADUATE of Massachusetts Undergraduate HISTORY History Journal, JOURNAL Vol. 3 [2019], Art. 1 2 ABSTRACT Domestic opposition to the government in Paris was a constant throughout the French Revolution. Although the revolutionary government repressed each instance of unrest, the various opposition movements’ motivations and goals provide a lens through which we can re-evaluate the values of liberty, equality, and justice that revolutionaries articulated. One domestic opposition movement, the Federalist Revolt of 1793, had major significance for the course of the Revolution. The Federalist Revolt raised questions about fundamental aspects of the Revolution itself: who were the sovereign people? Who claimed to represent the people? Was violence integral to claiming sovereignty? I explore a number of aspects of the Federalist Revolt. -

The Evolution of U.S. Military Policy from the Constitution to the Present

C O R P O R A T I O N The Evolution of U.S. Military Policy from the Constitution to the Present Gian Gentile, Michael E. Linick, Michael Shurkin For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1759 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9786-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since the earliest days of the Republic, American political and military leaders have debated and refined the national approach to providing an Army to win the nation’s independence and provide for its defense against all enemies, foreign and domestic. -

Fair Shares for All

FAIR SHARES FOR ALL JACOBIN EGALITARIANISM IN PRACT ICE JEAN-PIERRE GROSS This study explores the egalitarian policies pursued in the provinces during the radical phase of the French Revolution, but moves away from the habit of looking at such issues in terms of the Terror alone. It challenges revisionist readings of Jacobinism that dwell on its totalitarian potential or portray it as dangerously Utopian. The mainstream Jacobin agenda held out the promise of 'fair shares' and equal opportunities for all in a private-ownership market economy. It sought to achieve social justice without jeopardising human rights and tended thus to complement, rather than undermine, the liberal, individualist programme of the Revolution. The book stresses the relevance of the 'Enlightenment legacy', the close affinities between Girondins and Montagnards, the key role played by many lesser-known figures and the moral ascendancy of Robespierre. It reassesses the basic social and economic issues at stake in the Revolution, which cannot be adequately understood solely in terms of political discourse. Past and Present Publications Fair shares for all Past and Present Publications General Editor: JOANNA INNES, Somerville College, Oxford Past and Present Publications comprise books similar in character to the articles in the journal Past and Present. Whether the volumes in the series are collections of essays - some previously published, others new studies - or mono- graphs, they encompass a wide variety of scholarly and original works primarily concerned with social, economic and cultural changes, and their causes and consequences. They will appeal to both specialists and non-specialists and will endeavour to communicate the results of historical and allied research in readable and lively form. -

Timeline (PDF)

Timeline of the French Revolution 1789 1793 May 5 Estates General convened in Versailles Jan. 21 Execution of Louis XVI (and later, Marie Jun. 17 National Assembly Antoinette on Oct. 16) Jun. 20 Tennis Court Oath Feb. 1 France declares war on British and Dutch (and Jul. 11 Necker dismissed on Spain on Mar. 7) Jul. 13 Bourgeois militias in Paris Mar. 11 Counterrevolution starts in Vendée Jul. 14 Storming of the Bastille in Paris (official start of Apr. 6 Committee of Public Safety formed the French Revolution) Jun. 1-2 Mountain purges Girondins Jul. 16 Necker recalled Jul. 13 Marat assassinated Jul. 20 Great Fear begins in the countryside Jul. 27 Maximilien Robespierre joins CPS Aug. 4 Abolition of feudalism Aug. 10 Festival of Unity and Indivisibility Aug. 26 Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen Sept. 5 Terror the order of the day Oct. 5 Adoption of Revolutionary calendar 1791 1794 Jun. 20-21 Flight to Varennes Aug. 27 Declaration of Pillnitz Jun. 8 Festival of the Supreme Being Jul. 27 9 Thermidor: fall of Robespierre 1792 1795 Apr. 20 France declares war on Austria (and provokes Prussian declaration on Jun. 13) Apr. 5/Jul. 22 Treaties of Basel (Prussia and Spain resp.) Sept. 2-6 September massacres in Paris Oct. 5 Vendémiare uprising: “whiff of grapeshot” Sept. 20 Battle of Valmy Oct. 26 Directory established Sept. 21 Convention formally abolishes monarchy Sept. 22 Beginning of Year I (First Republic) 1797 Oct. 17 Treaty of Campoformio Nov. 21 Berlin Decree 1798 1807 Jul. 21 Battle of the Pyramids Aug. -

Marat/Sade Department of Theatre, Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons Department of Theatre Production Programs Department of Theatre Spring 4-6-2000 Marat/Sade Department of Theatre, Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/theatre_programs Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Department of Theatre, Florida International University, "Marat/Sade" (2000). Department of Theatre Production Programs. 28. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/theatre_programs/28 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theatre at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Theatre Production Programs by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~ -, ~ ~~acobiOs: a club of revolution.ary radicals founded in 1789 whose members e7~ : ""-·· first assemqled in an unused monastery of the Jacobins (Dominicans) in Paris. Urid~r the leadership of ROBESPIERRE,DANTON and MARAT,the Jacobins became the dominant force in the CONVENTIONwhere they sat Program notes on the lcft, facing their opponents, the GIRONDISTSwho sat on the right. After Robespierre's downfall the club was closed. Revolution begetscounter-revolution. Civil war spawns politicalmistrust and Lavoisier: Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier (1743-94), maj~r figure in modern bipartisanbetrayal. What nation ever discoversa lasting democraticpanacea chemistry,guillotined. when inequality, poverty, illiteracy and discrimination still abound? Each Marat: Jeari-Paul Marat ( 1743-93), physician and naturalist, author of med ge~erationin its turn has raised the callfor radicalchange. It is the order of ical, philosophical and political v.:-orks.During the early stages of the things to provoke change. -

Jacobins Maximilien Robespierre the Committee of Public Safety

The Reign of Terror Jacobins The most famous political group of the French Revolution was the Jacobins. Also known as the Society of the Friends of the Constitution, the club originally met at Versailles, organized by deputies of the Estates-General (and then National Assembly). They later met as a club in Paris. By July 1790, their membership grew to about 1,200 Parisian members, with 152 affiliate clubs; the number of members continued to grew thereafter. The club’s main concern was to protect what the revolutionaries had achieved so far—and prevent any reaction from the aristocracy. This desire resulted in the Reign of Terror. The Jacobins felt that it was their duty to catch anyone suspected of opposing the Revolution. The Jacobins also led the dechristianizing movement and organized Revolutionary festivals. Maximilien Robespierre Possibly the most well-known Jacobin was Maximilien Robespierre. He was trained as a lawyer and practiced law by representing poor people. When the Estates-General was summoned in 1789, the Third Estate elected him as one of their deputies. He was thirty years old. Robespierre was a quiet, simple man, with a weak voice. Yet he was able to make himself heard. He spoke more than five hundred times during the life of the National Assembly, and it was here that he gained supporters. He was a philosopher and sided with the ideals of the Enlightenment. He used this background to help shape the Declaration of the Rights of Man. He was a proponent of everything the Declaration stood for. He believed in equal rights, the right to hold office and join the national guard, and the right to petition.