Protests Around Parliament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trafalgar Square & Parliament Square Garden Activities and Hires

FM Internal Guidance – Trafalgar Square & Parliament Square Garden Activities and Hires The GLA do not permit (unless in exceptional circumstances in which GLA authorisation has been given in writing): • Private or exclusive parties/functions • ‘Roadshow’ activities which only have giveaways as the primary content of the event • ‘Flash mob’ activity • Overt branding and/or advertising within the event – however, there is scope for commercial activity • Offensive or adult themed materials in any printed format or computer generated/screened format. • Handouts or giveaways without an accompanying event • Infrastructure or dressing which may damage the fabric of the Trafalgar Square • Infrastructure on any part of Parliament Square Garden • Vehicle focused events on a pedestrian space - cars, motorbikes or double decker buses as the focus for example. • Busking without an accompanying event/ purpose • Use of balloons or inflatables • Use of stickers or any adhesive material • Any act which is against the Bye Laws and/or PRSR 2011 act • Pyrotechnics, candles or any other element requiring a naked flame for ignition or that gives out sparks or smoke. • Balloon releases • Drones • Any licensable activity at any time throughout an event or hire without prior written authorisation of the GLA. Further detail 1. Sports tournament – Parliament square is in the centre of very busy roads and Trafalgar Square is surrounded on three sides by busy roads. The GLA cannot accommodate a full sports match because of the safety issues. They also conflict with the byelaws and impact public access around the square. We can accommodate sports activations as a low-key press call. 2. Cigarette/alcohol & gambling activations – The GLA does not support advertising of as this would contradict all current policy and health initiatives that the GLA is driving forward for Londoners. -

Character Overview Westminster Has 56 Designated Conservation Areas

Westminster’s Conservation Areas - Character Overview Westminster has 56 designated conservation areas which cover over 76% of the City. These cover a diverse range of townscapes from all periods of the City’s development and their distinctive character reflects Westminster’s differing roles at the heart of national life and government, as a business and commercial centre, and as home to diverse residential communities. A significant number are more residential areas often dominated by Georgian and Victorian terraced housing but there are also conservation areas which are focused on enclaves of later housing development, including innovative post-war housing estates. Some of the conservation areas in south Westminster are dominated by government and institutional uses and in mixed central areas such as Soho and Marylebone, it is the historic layout and the dense urban character combined with the mix of uses which creates distinctive local character. Despite its dense urban character, however, more than a third of the City is open space and our Royal Parks are also designated conservation areas. Many of Westminster’s conservation areas have a high proportion of listed buildings and some contain townscape of more than local significance. Below provides a brief summary overview of the character of each of these areas and their designation dates. The conservation area audits and other documentation listed should be referred to for more detail on individual areas. 1. Adelphi The Adelphi takes its name from the 18th Century development of residential terraces by the Adam brothers and is located immediately to the south of the Strand. The southern boundary of the conservation area is the former shoreline of the Thames. -

HOLBA-Insights-Report-Jul-20.Pdf

HEART OF LONDON JULY AREA PERFORMANCE HEART OF LONDON AREA PERFORMANCE CONTENTS JULY 2020 EDITION INTRODUCTION 02 Welcome to our area performance report. This monthly summary provides trends in footfall, spending SUMMARY ANALYSIS 03 and much more, in the Heart of London area. Focusing on Leicester Square, Piccadilly Circus, Haymarket, Piccadilly and FOOTFALL TRENDS 04 St James’s, find out exactly how our area has performed FOOTFALL OVERVIEW 05 throughout the month. HOURLY FOOTFALL 06 The report is available exclusively to members, and explores REGIONAL FOOTFALL 07 changes in trends that impact the performance of our area, allowing your business to plan with confidence and make the COVID-19 AND FOOTFALL 08 most of being in the heart of London. YOUR FEEDBACK IS IMPORTANT TO US PROPERTY & INVESTMENT 09 PLEASE CLICK ON THE BUTTON INVESTMENT 10 TO REQUEST NEW DATA OR ANALYSIS PROPERTY PERFORMANCE 11 LEASE AVAILABILITY 12 EVENTS & ACTIVITY 13 IMPACT CALENDAR 14 GLOSSARY 15 See our Glossary for more detail on data sources and definitions. 2 HEART OF LONDON AREA PERFORMANCE SUMMARY ANALYSIS – JULY 2020 Rainfall (mm) 2020 2019 500K 25 YEAR ON YEAR FOOTFALL 450K -72% Footfall in the current month compared to the same month last year 400K 20 350K 300K 15 MONTH ON MONTH FOOTFALL 250K +97% Footfall in the current month compared Footfall 200K 10 to the previous month Rainfall (mm) Rainfall 150K 100K 5 YEAR TO DATE FOOTFALL 50K -58% Footfall in the current year to date K 0 compared to the same period last year M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 Week 28 Week 29 Week 30 Week 31 July trend summary • Like-for-like footfall in the Heart of London area was down 72% in July 2020 compared to the same month last year. -

Restoration of the Right to Protest at Parliament

Law, Crime and History (2013) 1 LETTING DOWN THE DRAWBRIDGE: RESTORATION OF THE RIGHT TO PROTEST AT PARLIAMENT Kiron Reid1 Abstract This article analyses the history of the prohibition of protests around Parliament under the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005. This prohibited any demonstrations of one or more persons within one square kilometre of the Houses of Parliament unless permission had been obtained in writing from the police in advance. This measure both formed part of a pattern of the then Labour Government to restrict protest and increase police powers, and was symbolically important in restricting protest that was directed at politicians at a time when politicians have been very unpopular. The Government of Tony Blair had been embarrassed by a one-man protest by peace campaigner, Brian Haw. In response to sustained defiance, Mr. Blair’s successor as Labour Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, and opposition Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs pledged to remove the restrictions, but this was not acted on by Parliament until September 2011. This article argues that the original restrictions were unnecessary, and that the much narrower successor provisions could be improved by being drafted more specifically. Keywords: protest, demonstration, protest at Parliament, freedom of speech, Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005, Brian Haw. Introduction This is about the sorry tale of sections 132-138 Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 (SOCPA).2 These prohibited any demonstrations of one or more persons within one square kilometre of the Houses of Parliament unless advance written permission had been obtained from the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis. -

Sessional Orders and Resolutions

House of Commons Procedure Committee Sessional Orders and Resolutions Third Report of Session 2002–03 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 5 November 2003 HC 855 Published on 19 November 2003 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £11.00 The Procedure Committee The Procedure Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider the practice and procedure of the House in the conduct of public business, and to make recommendations. Current membership Sir Nicholas Winterton MP (Conservative, Macclesfield) (Chairman) Mr Peter Atkinson MP (Conservative, Hexham) Mr John Burnett MP (Liberal Democrat, Torridge and West Devon) David Hamilton MP (Labour, Midlothian) Mr Eric Illsley MP (Labour, Barnsley Central) Huw Irranca-Davies MP (Labour, Ogmore) Eric Joyce MP (Labour, Falkirk West) Mr Iain Luke MP (Labour, Dundee East) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld and Kilsyth) Mr Tony McWalter MP (Labour, Hemel Hempstead) Sir Robert Smith MP (Liberal Democrat, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) Mr Desmond Swayne MP (Conservative, New Forest West) David Wright MP (Labour, Telford) Powers The powers of the committee are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 147. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at http://www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_ committees/procedure_committee.cfm. A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

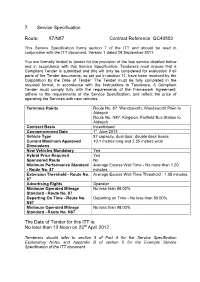

7. Service Specification Route

7. Service Specification Route: 87/N87 Contract Reference QC40803 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Terminus Points Route No. 87: Wandsworth, Wandsworth Plain to Aldwych Route No. N87: Kingston, Fairfield Bus Station to Aldwych Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 1st June 2013 Vehicle Type 87 capacity, dual door, double deck buses Current Maximum Approved 10.1 metres long and 2.55 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.20 - Route No. 87 minutes Extension Threshold - Route No. Average Excess Wait Time Threshold - 1.05 minutes 87 Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard - Route No. 87 Departing On Time - Route No. Departing on Time - No less than 85.00% N87 Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard - Route No. -

Depleted Uranium P 4 We Talk a Lot About the Loyalty of These Daisaku Ikeda P 5 2 Pm Animals, and Their Willingness to Serve Gyosei Handa P 5 Us

ABOLISHABOLISH WARWAR Newsletter No: 9 Autumn 2007 Price per Issue £1 Remembrance Day - What will you be doing? Whether you wear red poppies, white poppies or both, whether you take part in a Remembrance service or The MAW AGM not, or you organise an event to question the fact of war, the day we Saturday 10th November remember those who have died in 11 am - 3 pm war is the day when MAW’s message should be loud and clear - war must Wesley’s Chapel 49 City Road end if we are not to add yet more London EC1Y 1AU names to our memorials. (nearest tube station Old Street) Animals in War Among the innocents we should Speaker: Craig Murray remember in November are the Craig is well known as the UK Ambassador to Uzbekistan who highlighted the human rights abuses he found there, millions of animals that took part in embarrassing the proponents of the ‘War on Terror’ with the and died for our political failures. result he is no longer in the Diplomatic Corps. He is a In 2004 a new monument appeared in fascinating, informative and funny speaker, with a wealth of London - the Animals in War experience to draw on. “Craig Murray has been a deep Memorial, inspired by Jilly Cooper’s embarrassment to the entire Foreign Office.” Jack Straw book of the same name. It ‘honours The AGM is open to all and is free. If you can get to the millions of conscripted animals London, then get to the AGM. And bring your friends. -

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007 Yesterday an extraordinary work of political-conceptual-appropriation-installation art went on view at Tate Britain. There’ll be those who say it isn’t art – and this time they may even have a point. It’s a punch in the face, and a bunch of questions. I’m not sure if I, or the Tate, or the artist, know entirely what the work is up to. But a chronology will help. June 2001: Brian Haw, a former merchant seaman and cabinet-maker, begins his pavement vigil in Parliament Square. Initially in opposition to sanctions on Iraq, the focus of his protest shifts to the “war on terror” and then the Iraq war. Its emphasis is on the killing of children. Over the next five years, his line of placards – with many additions from the public - becomes an installation 40 metres long. April 2005: Parliament passes the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act. Section 132 removes the right to unauthorised demonstration within one kilometre of Parliament Square. This embraces Whitehall, Westminster Abbey, the Home Office, New Scotland Yard and the London Eye (though Trafalgar Square is exempted). As it happens, the perimeter of the exclusion zone passes cleanly through both Buckingham Palace and Tate Britain. May 2006: The Metropolitan Police serve notice on Brian Haw to remove his display. The artist Mark Wallinger, best known for Ecce Homo (a statue of Jesus placed on the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square), is invited by Tate Britain to propose an exhibition for its long central gallery. -

SCHOOL TRIP to LONDON Restaurant “The Albert” 52 Victoria Street – SW1H 0NP Londra –

Progetto extra-scolastico in CLIL ”In Viaggio con la scuola e nella scuola”. Docenti: Prof.ssa Colonna Giuseppina e Prof.ssa Palazzo Ornella Where we stay:47 Lillie Road - SW6 1UD LONDRA - Istituto Comprensivo Statale “Palombara Sabina” What we visit :British Museum, Tower Bridge, The Tower of London, The Houses of Parlia- Tel. 0044 207 6100880 ment,The Clock Tower, St Paul’s Cathedral, Buckingham Palace, Kensington Gardens,Hyde A/S 2013-2014 Park, Henrietta Street, Piccadilly Circus, Trafalgar Square, ,Covent Garden, Harrods, Royal Where we eat: Restaurant “The Devereux” 20 Devereux Opera House. Court – WC2R 3JJ ; SCHOOL TRIP TO LONDON Restaurant “The Albert” 52 Victoria Street – SW1H 0NP Londra – Henrietta St.: Wednesday (Sept. 15, 1/2 past 8). Here I am, my dearest Cassandra, seated in the breakfast, dining, sit- STATUES OF LONDON ting-room, beginning with all my might…We had a very good journey, weather and roads excellent; the three first stages for 1s. 6d., and our only misadventure the being delayed about a quarter of an hour at Kingston for horses, and being obliged to put up with a pair belonging to a hackney coach and their coachman, which left no room on the ba- Jane Austen’s brother, Henry, lived with his wife Eliza in Henrietta Street. Jane rouche box for Lizzy, who was to have gone her last stage there as she Austen often stayed at his home to work on her manuscripts and get them ready for did the first; consequently we were all four within, which was a little These are the statues of Charlie Chaplin, Peter publication. -

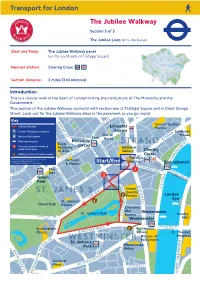

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

Middle Saxon and Later Archaeological Remains in Whitehall

MIDDLE SAXON AND LATER ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS IN WHITEHALL Paw Jorgensen With contributions by Jonathan Butler, Kevin Hayward, Chris Jarrett and Kevin Rielly SUMMARY Guards Road to the west, the Embankment to the east, Parliament Square to the south Archaeological investigations undertaken during the and Great Scotland Yard to the north (Figs streetscape improvements in Whitehall revealed the 2, 2a, 2b). Bordering upon the site are remains of several periods of activity. Middle Saxon governmental offices, mostly dating to the activity most likely associated with that previously late 19th and 20th centuries, many of which found at the Old Treasury Building in the 1960s was are Listed Buildings. In total 78 Listed revealed on Whitehall opposite the west end of Horse Buildings are located immediately adjacent Guards Avenue. Elsewhere masonry associated with to the site; of these, 14 are Grade I listed, York Place, the Archbishop of York’s official residence 17 Grade II* listed, and 47 Grade II listed; in London, and Whitehall Palace was found. Later these include Queen Mary’s Steps, the Ban- remains consisted of buildings which were constructed queting House, the Ministry of Defence in the 18th and 19th century following the destruction Main Building, and the Cabinet Office, Privy of Whitehall Palace in two fires at the end of the 17th Council and Treasury Building, all of which century. to varying degrees have incorporated part of the fabric of Whitehall Palace into the INTRODUCTION current buildings and structures. Furthermore, the entire site lies within the Pre-Construct Archaeology was commiss- Lundenwic and Thorney Island Area of Spec- ioned by Atkins Heritage acting on behalf ial Archaeological Priority and immediately of the City of Westminster to undertake a to the south is the World Heritage Site of watching-brief during streetscape improve- Westminster Palace, Westminster Abbey and ments along Whitehall and the adjoining St Margaret’s Church (WHS number 462). -

148 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

148 bus time schedule & line map 148 White City - Camberwell Green View In Website Mode The 148 bus line (White City - Camberwell Green) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Camberwell Green: 24 hours (2) White City: 24 hours Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 148 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 148 bus arriving. Direction: Camberwell Green 148 bus Time Schedule 40 stops Camberwell Green Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 24 hours Monday 24 hours White City Bus Station (WK) Tuesday 24 hours Ariel Way / White City Bus Station (WB) Wednesday 24 hours Uxbridge Rd / Westƒeld Shopping Centre (T) Thursday 24 hours 58 Bulwer Street, London Friday 24 hours Shepherd's Bush Station (X) 74 Shepherd's Bush Green, London Saturday 24 hours Royal Crescent (HJ) Norland Square (HK) 148 bus Info Holland Park Station (HL) Direction: Camberwell Green Boyne Terrace Mews, London Stops: 40 Trip Duration: 64 min Notting Hill Gate Stn / Hillgate St (D) Line Summary: White City Bus Station (WK), Ariel Notting Hill Gate, London Way / White City Bus Station (WB), Uxbridge Rd / Westƒeld Shopping Centre (T), Shepherd's Bush Palace Gardens Terrace (M) Station (X), Royal Crescent (HJ), Norland Square 14 Notting Hill Gate, London (HK), Holland Park Station (HL), Notting Hill Gate Stn / Hillgate St (D), Palace Gardens Terrace (M), Orme Orme Square (T) Square (T), Queensway Station (C), Leinster Terrace Orme Court, London (LF), Lancaster Gate (LE), Lancaster Gate Station (LK), Victoria Gate (LB), Hyde Park Street