UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliament of India R a J Y a S a B H a Committees

Com. Co-ord. Sec. PARLIAMENT OF INDIA R A J Y A S A B H A COMMITTEES OF RAJYA SABHA AND OTHER PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES AND BODIES ON WHICH RAJYA SABHA IS REPRESENTED (Corrected upto 4th September, 2020) RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI (4th September, 2020) Website: http://www.rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] OFFICERS OF RAJYA SABHA CHAIRMAN Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu SECRETARY-GENERAL Shri Desh Deepak Verma PREFACE The publication aims at providing information on Members of Rajya Sabha serving on various Committees of Rajya Sabha, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees, Joint Committees and other Bodies as on 30th June, 2020. The names of Chairmen of the various Standing Committees and Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees along with their local residential addresses and telephone numbers have also been shown at the beginning of the publication. The names of Members of the Lok Sabha serving on the Joint Committees on which Rajya Sabha is represented have also been included under the respective Committees for information. Change of nominations/elections of Members of Rajya Sabha in various Parliamentary Committees/Statutory Bodies is an ongoing process. As such, some information contained in the publication may undergo change by the time this is brought out. When new nominations/elections of Members to Committees/Statutory Bodies are made or changes in these take place, the same get updated in the Rajya Sabha website. The main purpose of this publication, however, is to serve as a primary source of information on Members representing various Committees and other Bodies on which Rajya Sabha is represented upto a particular period. -

1 Shri Adhikari, Deepak

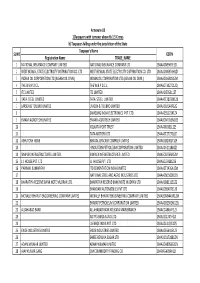

S T A T E M E N T - IV STATEMENT SHOWING MEMBER-WISE ANALYSIS OF QUESTIONS ADMITTED AND CLUBBED ADMITTED CLUBBED Sl.No. Member's Name [Constituency] Total SQ. USQ. SNQ. SQ. USQ. SNQ. 1 SHRI ADHIKARI, DEEPAK (DEV) [GHATAL] 0 8 0 1 9 2 SHRI ADHIKARI, SISIR KUMAR [KANTHI] 0 17 0 1 18 3 SHRI ADHIKARI, DIBYENDU [TAMLUK] 0 17 0 2 19 4 SHRI AGRAWAL, RAJENDRA [MEERUT] 3 15 0 4 22 5 SMT. AHMED, SAJDA [ULUBERIA] 4 9 0 2 15 6 SHRI AJMAL, BADRUDDIN M. [DHUBRI-4] 0 20 0 4 24 7 KUN ALI, DANISH [Amroha] 2 14 0 0 16 8 SMT. AMBAREESH, SUMALATHA [MANDYA] 0 3 0 1 4 9 SHRI ANAND, D.M. KATHIR [VELLORE] 0 9 0 0 9 10 SHRI ANNADURAI, C.N. [TIRUVANNAMALAI] 0 9 0 0 9 11 SH. ANTONY, ANTO [PATHANAMTHITTA] 0 16 2 7 25 12 ADV. ARIFF, A.M. [ALAPPUZHA] 1 15 0 5 21 13 SHRI AUJLA, GURJEET SINGH [AMRITSAR] 1 14 0 6 21 14 SMT. AZAD, SANGEETA [LALGANJ (SC)] 0 5 0 0 5 15 SHRI BAALU, T.R [SRIPERUMBUDUR] 3 12 1 2 18 16 SHRI BADAL, SUKHBIR SINGH [FIROZPUR] 0 3 0 0 3 17 SHRI BAGHEL, VIJAY [DURG-7] 1 9 0 2 12 18 SHRI BAIJ, DEEPAK [BASTAR (ST)-10] 2 17 0 0 19 19 SHRI BANERJEE, KALYAN [SREERAMPUR] 0 4 0 0 4 20 SHRI BANERJEE, PRASUN [HOWRAH] 0 13 0 6 19 21 SHRI BAPAT, GIRISH BHALCHANDRA [PUNE] 0 12 0 2 14 22 SHRI BARNE, SHRIRANG APPA [MAVAL] 1 9 3 42 55 23 SHRI BARUAH, PRADAN [LAKHIMPUR-14] 0 4 0 0 4 24 SHRI BASAVARAJ, G.S. -

Here in the United Online Premieres Too

Image : Self- portrait by Chila Kumari Singh Burman Welcome back to the festival, which this Dive deep into our Extra-Ordinary Lives strand with amazing dramas and year has evolved into a hybrid festival. documentaries from across South Asia. Including the must-see Ahimsa: Gandhi, You can watch it in cinemas in London, The Power of The Powerless, a documentary on the incredible global impact of Birmingham, and Manchester, or on Gandhi’s non-violence ideas; Abhijaan, an inspiring biopic exploring the life of your own sofa at home, via our digital the late and great Bengali actor Soumitra Chatterjee; Black comedy Ashes On a site www.LoveLIFFatHome.com, that Road Trip; and Tiger Award winner at Rotterdam Pebbles. Look out for selected is accessible anywhere in the United online premieres too. Kingdom. Our talks and certain events We also introduce a new strand dedicated to ecology-related films, calledSave CARY RAJINDER SAWHNEY are also accessible worldwide. The Planet, with some stirring features about lives affected by deforestation and rising sea levels, and how people are meeting the challenge. A big personal thanks to all our audiences who stayed with the festival last We are expecting a host of special guests as usual and do check out our brilliant year and helped make it one of the few success stories in the film industry. This online In Conversations with Indian talent in June - where we will be joined year’s festival is dedicated to you with love. by Bollywood Director Karan Johar, and rapidly rising talented actors Shruti Highlights of this year’s festival include our inspiring Opening Night Gala Haasan and Janhvi Kapoor, as well as featuring some very informative online WOMB about one woman gender activist who incredibly walks the entire Q&As on all our films. -

The Saffron Wave Meets the Silent Revolution: Why the Poor Vote for Hindu Nationalism in India

THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tariq Thachil August 2009 © 2009 Tariq Thachil THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA Tariq Thachil, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 How do religious parties with historically elite support bases win the mass support required to succeed in democratic politics? This dissertation examines why the world’s largest such party, the upper-caste, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has experienced variable success in wooing poor Hindu populations across India. Briefly, my research demonstrates that neither conventional clientelist techniques used by elite parties, nor strategies of ideological polarization favored by religious parties, explain the BJP’s pattern of success with poor Hindus. Instead the party has relied on the efforts of its ‘social service’ organizational affiliates in the broader Hindu nationalist movement. The dissertation articulates and tests several hypotheses about the efficacy of this organizational approach in forging party-voter linkages at the national, state, district, and individual level, employing a multi-level research design including a range of statistical and qualitative techniques of analysis. In doing so, the dissertation utilizes national and author-conducted local survey data, extensive interviews, and close observation of Hindu nationalist recruitment techniques collected over thirteen months of fieldwork. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Tariq Thachil was born in New Delhi, India. He received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stanford University in 2003. -

Chemistry of Transition Metal Complexes with O- And/Or N- Donor Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization and Study of Reactivity

Chemistry of Transition Metal Complexes with O- and/or N- Donor Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization and Study of Reactivity Dissertation submitted to the National Institute of Technology Rourkela in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry by Satabdi Roy (Roll No. 512CY105) Under the supervision of Prof. Rupam Dinda January, 2017 Department of Chemistry National Institute of Technology, Rourkela Rourkela-769008, Odisha, India Department of Chemistry National Institute of Technology Rourkela Certificate of Examination Roll Number: 512CY105 Name: Satabdi Roy Title of Dissertation: “Chemistry of Transition Metal Complexes with O- and/or N- Donor Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization and Study of Reactivity” We the below signed, after checking the dissertation mentioned above and the official record book (s) of the student, hereby state our approval of the dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry at National Institute of Technology Rourkela. We are satisfied with the volume, quality, correctness, and originality of the work. Rupam Dinda Supervisor Debasish Sarkar Saurav Chatterjee Member (DSC) Member (DSC) & HOD V. Sivakumar Member (DSC) Examiner Garudadhwaj Hota Chairman (DSC) Department of Chemistry National Institute of Technology Rourkela Prof. Rupam Dinda Associate Professor Supervisor’s Certificate This is to certify that the work presented in this dissertation entitled “Chemistry of Transition Metal Complexes with O- and/or N- Donor Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization and Study of Reactivity” by Satabdi Roy, Roll No. 512CY105 of the Department of Chemistry, National Institute of Technology, Rourkela, India, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy is a record of bona fide research work carried out by her under my guidance and supervision. -

Development Effectiveness Brief: India and ADB

DEVELOPMENT EFFECTIVENESS BRIEF INDIA AND ADB THREE DECADES OF ENDURING PARTNERSHIP DECEMBER 2018 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK DEVELOPMENT EFFECTIVENESS BRIEF DEVELOPMENT EFFECTIVENESS BRIEF INDIA AND ADB THREE DECADES OF ENDURING PARTNERSHIP DECEMBER 2018 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2018 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2018. ISBN 978-92-9261-446-1 (print), 978-92-9261-447-8 (electronic) Publication Stock No. BRF189782 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/BRF189782 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. By using the content of this publication, you agree to be bound by the terms of this license. For attribution, translations, adaptations, and permissions, please read the provisions and terms of use at https://www.adb.org/terms-use#openaccess. This CC license does not apply to non-ADB copyright materials in this publication. -

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Notice-21.01.2021.Pdf

"A" 3 4 5 Typed Copy PRISONER’S PETITION (Permitted under Jail Code Rule 615) From (Name, Member and Class) Sri Sudipta Sen son of Late Nripendra Narayan Sen Who was sentenced on 03/05/2013 to as an UTP Under Section 405/406 by 420 In Ld. Judge C.B.I. Special Court, Kolkata To, 1. The President of India 2. Chief Justice of India 3. Director C.B.I. 4. C.M.M. Kolkata, Most Hon’ble and respected 5. Prime Minister of India 6. Chief Minister of Delhi Respected Sir, I, Sri Sudipta Sen son of Late Nripendra Narayan Sen like to submit my humble submission before you. I have been in the judicial custody for last eight years. Before one and half years I had written one letter to Director C.B.I., Chief Justice of Kolkata High Court, D.G.P. of State of West Bengal, Home Secretary of West Bengal. I want to tell something about SARADA investigation. Because I am the Managing Director of Sarada. In year 2013 in the month April and 2014, 9th May Hon’ble Supreme Court of India, Hon’ble Justice T.S. Thakar and Hon’ble Justice Nagapa passed and orsder for transfer all cases (illegible) in the State of West Bengal to C.B.I. Further 2014 in the month of May C.B.I. started 6 Fund (illegible) of fund disturbed the system. Otherwise it could have been the largest media house of Bengal without taking any help from Government. I did not take any advantage from any political party or Government. -

The Urban Social Pattern of Navi Mumbai, India

The Urban Social Pattern of Navi Mumbai, India Malathi Ananthakrishnan Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Urban and Regional Planning John Browder, Chair Wendy Jacobson Paul Knox April , 1998 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: urban social pattern, Navi Mumbai, Bombay, urban planning - India Copyright 1998, Malathi Ananthakrishnan The Urban Social Pattern of Navi Mumbai, India Malathi Ananthakrishnan (ABSTRACT) This research thesis examines the emerging trends in urban social patterns in Navi Mumbai, India. Unlike the other planned cities of India, Navi Mumbai was specifically built as a planned decentralization of a large metropolitan city. The research focuses on explaining the urban social pattern of this particular case study. An urban social pattern reflects the social characteristics of the urban setting. In the case of Navi Mumbai, the government had a social agenda of promoting a social pattern based on socioeconomic distribution rather than an ethnic one. Analysis of the data provides an insight to the results of this social agenda, and provides a basis to frame new ones. Thus, the study not only addresses a basic research question, but also has policy implications. The research involves a comprehensive review of secondary source material to establish the theoretical framework for the research. The review also involves an extensive inspection of urban social patterns across the world to better contextualize this particular case study. The research puts forth a model that explains the social pattern of Navi Mumbai by social area analysis using variables, which are drawn from social aspects of any city and indigenous factors of Indian settlements. -

Juliet and Julie As Subalterns in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet

International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL) Volume 7, Issue 3, March 2019, PP 41-46 ISSN 2347-3126 (Print) & ISSN 2347-3134 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2347-3134.0703006 www.arcjournals.org Juliet and Julie as Subalterns in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Aparna Sen’s Arshinagar Mst. Dil Rifat Sayed English Discipline, Khulna University, Bangladesh *Corresponding Author Mst. Dil Rifat Sayed, English Discipline, Khulna University, Bangladesh Abstract: Juliet in William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and in its 2015 film adaptation Arshinagar by Aparna Sen is marginalized like a subaltern, though the ways of her marginalization are different. She is never allowed to raise her voice in the patriarchal society. Subalternity in Shakespeare’s Juliet appears intense but Aparna Sen’s Julie (counterpart of Juliet) becomes doubly subaltern because of her gender as well as her religion. Patriarchal hegemony surrounds both Shakespeare’s Juliet and Aparna Sen’s Julie, but religious orthodoxy and patriarchal hegemony work together to make Sen’s Julie subaltern. This paper traces the ways in which Juliet or Julie is made subaltern. It also shows how Juliet and Julie are denied freedom of speech in the original text and in its adaptation. Keywords: Patriarchy, Religion, Silent, Subaltern, Subordinate 1. INTRODUCTION Arshinagar is a 2015 Bengali musical romance drama, a modernized version of William Shakespeare‟s Romeo and Juliet. Juliet in Shakespeare‟s Romeo and Juliet is marginalized like a subaltern where Julekha Khan or Julie (counterpart of Juliet) in Aparna Sen‟s Arshinagar is doubly marginalized. Critics have examined William Shakespeare‟s Romeo and Juliet and Aparna Sen‟s Arshinagar from multiple perspectives but most of them overlook the role of Juliet / Julie and none of them has explored her position as a subaltern. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

Interweaving Dystopian and Utopian Spaces, Constructing Social Realism on Screen: Bakita Byaktigato/The Rest Is Personal

Utopian Art and Literature from Modern India How to Cite: Sen, S 2019 Interweaving Dystopian and Utopian Spaces, Constructing Social Realism on Screen: Bakita Byaktigato/The Rest is Personal. Open Library of Humanities, 5(1): 14, pp. 1–27. DOI: https://doi. org/10.16995/olh.410 Published: 08 February 2019 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of Open Library of Humanities, which is a journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Open Library of Humanities is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. Sanghita Sen, ‘Interweaving Dystopian and Utopian Spaces, Constructing Social Realism on Screen: Bakita Byaktigato/ The Rest is Personal’ (2019) 5(1): 14 Open Library of Humanities. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.410 UTOPIAN ART AND LITERATURE FROM MODERN INDIA Interweaving Dystopian and Utopian Spaces, Constructing Social Realism on Screen: Bakita Byaktigato/The Rest is Personal Sanghita Sen University of St Andrews, UK [email protected] This article investigates the role of utopian and dystopian spaces in the construction of social realism in Bakita Byaktigato/The Rest is Personal (Pradipta Bhattacharya, 2013).