H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXII-37

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

MA Political Science Programme

Department of Political Science, University of Delhi UNIVERSITY OF DELHI MASTER OF ARTS in POLITICAL SCIENCE (M.A. in Political Science) (Effective from Academic Year 2019-20) PROGRAMME BROCHURE Revised Syllabus as approved by Academic Council on XXXX, 2019 and Executive Council on YYYY, 2019 Department of Political Science, University of Delhi 1 | Page Table of Contents I. About the Department ................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 About the Programme: ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 About the Process of Course Development Involving Diverse Stakeholders .......................... 4 II. Introduction to CBCS (Choice Based Credit System) .............................................................. 5 III. M.A. Political Science Programme Details: ............................................................................ 6 IV. Semester wise Details of M.A.in Political Science Course....................................................... 9 4.1 Semester wise Details ................................................................................................................ 9 4.2 List of Elective Course (wherever applicable to be mentioned area wise) ............................ 10 4.3 Eligibility for Admission: ....................................................................................................... 13 4.4 Reservations/ Concessions: .................................................................................................... -

H-Diplo ESSAY 319

H-Diplo ESSAY 319 Essay Series on Learning the Scholar’s Craft: Reflections of Historians and International Relations Scholars 2 March 2021 Contingent Histories https://hdiplo.org/to/E319 Series Editor: Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Essay by Fredrik Logevall, Harvard University aybe it was Laurence Olivier who made me a historian. One evening in late 1975, not long after my family emigrated from Västerås, Sweden, to Vancouver, B.C., I happened upon the BBC’s “The World at War,” which is still for my money the gold standard among World War II documentaries. The astonishing archival footage Mdrew me right in, but so did Olivier’s narration, with its calm authority and elevated diction. Even today I can recite from memory his opening lines in the first episode, written in spare, declarative style by Neal Ascherson: Down this road, on a summer day in 1944, the soldiers came. Nobody lives here now. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years was dead. This is Oradour-sur-Glane, in France. I caught most of the episodes that fall. A year or so later, at age thirteen, I watched the entire series, all 23 hours, if anything more enthralled than the first time. (My English had improved in the interval.) Hungry for more, I began reading books on the war—the first one, Peter Calvocoressi and Guy Wint’s engrossing Total War, still adorns a shelf in my home office, ageless and imposing.1 I wasn’t exactly studious—my grades were middling, at best (“Fredrik needs to learn to apply himself,” read report card upon report card), and I preferred to spend my time on the tennis court or hanging around with pals—but history fascinated me. -

George F. Kennan: an American Life

George F. Kennan: An American Life Saturday, April 7, 2012 Griffin Hall, Room 3 Williams College Sponsored by the Stanley Kaplan Program in American Foreign Policy Saturday, April 7, 2012 8:45 - 10:00 AM The Making of a Cold War Intellectual Frank Costigliola, University of Connecticut Walter Hixson, University of Akron Christina Klein, Boston College Mark Lawrence, UT-Austin/Williams College Frank Ninkovich, St. John’s University 10:15 - 11:45 AM Kennan and the Art of Foreign Policy David Ekbladh, Tufts University Hope Harrison, George Washington University Fredrik Logevall, Cornell University David Mayers, Boston University Anders Stephanson, Columbia University 12:00 - 1:00 PM Lunch 1:00 - 2:15 PM Kennan, Realism, and American Grand Strategy David Kaiser, Naval War College Douglas Macdonald, Colgate University James McAllister, Williams College Mark Sheetz, Belfer Center at Harvard University 2:15 - 2:30 PM Closing Remarks John Lewis Gaddis, Yale University Conference Participants Frank Costigliola, University of Connecticut Frank Costigliola is a Professor of history at the University of Connecticut. He is the author, most recently, of Roosevelt’s Lost Alliances (Princeton, 2012) and he is currently editing the diaries of George F. Kennan. David Ekbladh, Tufts University David Ekbladh is Assistant Professor of history at Tufts University. He is currently at work on a book entitled Look at the World: The Birth of an American Globalism in the 1930s, that explores the wide-ranging changes in how the United States perceived and engaged the world. His first book, The Great American Mission: Modernization and the Construction of an American World Order (Princeton University Press, 2010), won the Stuart L. -

Public Radio International, Lyndon Johnson's Presidency and the War

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Public Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/public/media- projects-production-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Public Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: LBJ’s War: An Oral History Institution: Public Radio International, Inc. Project Director: Melinda Ward Grant Program: Media Projects Production 400 7th Street, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8269 F 202.606.8557 E [email protected] www.neh.gov PUBLIC RADIO INTERNATIONAL (PRI) Request to the National Endowment for the Humanities “LBJ’S War: An Oral History” Project Narrative – January 2016 A. NATURE OF THE REQUEST Public Radio International (PRI) requests a grant of $166,450 in support of LBJ’s War , an innovative oral history project to be produced in partnership with independent radio producer Stephen Atlas. LBJ’s War presents the story of how the U.S. -

AHA Colloquium

Cover.indd 1 13/10/20 12:51 AM Thank you to our generous sponsors: Platinum Gold Bronze Cover2.indd 1 19/10/20 9:42 PM 2021 Annual Meeting Program Program Editorial Staff Debbie Ann Doyle, Editor and Meetings Manager With assistance from Victor Medina Del Toro, Liz Townsend, and Laura Ansley Program Book 2021_FM.indd 1 26/10/20 8:59 PM 400 A Street SE Washington, DC 20003-3889 202-544-2422 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.historians.org Perspectives: historians.org/perspectives Facebook: facebook.com/AHAhistorians Twitter: @AHAHistorians 2020 Elected Officers President: Mary Lindemann, University of Miami Past President: John R. McNeill, Georgetown University President-elect: Jacqueline Jones, University of Texas at Austin Vice President, Professional Division: Rita Chin, University of Michigan (2023) Vice President, Research Division: Sophia Rosenfeld, University of Pennsylvania (2021) Vice President, Teaching Division: Laura McEnaney, Whittier College (2022) 2020 Elected Councilors Research Division: Melissa Bokovoy, University of New Mexico (2021) Christopher R. Boyer, Northern Arizona University (2022) Sara Georgini, Massachusetts Historical Society (2023) Teaching Division: Craig Perrier, Fairfax County Public Schools Mary Lindemann (2021) Professor of History Alexandra Hui, Mississippi State University (2022) University of Miami Shannon Bontrager, Georgia Highlands College (2023) President of the American Historical Association Professional Division: Mary Elliott, Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (2021) Nerina Rustomji, St. John’s University (2022) Reginald K. Ellis, Florida A&M University (2023) At Large: Sarah Mellors, Missouri State University (2021) 2020 Appointed Officers Executive Director: James Grossman AHR Editor: Alex Lichtenstein, Indiana University, Bloomington Treasurer: William F. -

2018 Annual Report the Gilder Lehrman Institute Network in 2018

2018 ANNUAL REPORT THE GILDER LEHRMAN INSTITUTE NETWORK IN 2018 Over More than 20,000 40,000 5.6 million 750 Affiliate Schools K-12 teachers K-12 students master teachers Over Approximately 1,133 elementary, middle, 1,000 4 million and high school students historians unique website visitors entered a GLI Essay Contest More than Approximately 1,600 60,000 More than 1,011 middle and high Title I high school 428,000 educators in the school students in students in the students used 2018 Teacher GLI Saturday Hamilton Education GLI’s AP US History Seminar program Academies Program Study Guide (8% growth from 2017) 5,663 There were more than elementary, middle, and 2,114 high school teachers teachers received 455 nominated to be a professional development course enrollments in the History Teacher of the Year provided through Teaching Pace-Gilder Lehrman MA in (over 100% growth from 2017) Literacy through History American History program. OUR MISSION Students enjoy their free copies of David Blight’s Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom at the David Blight lecture in New York City, October 2018. FOUNDED IN 1994 BY RICHARD GILDER AND LEWIS E. LEHRMAN, visionaries and lifelong supporters of American history education, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is the leading nonprofit organization dedicated to K–12 history education while also serving the general public. The Institute’s mission is to promote the knowledge and understanding of American history through educational programs and resources. At the Institute’s core is the Gilder Lehrman Collection, one of the great archives in Amer- ican history. -

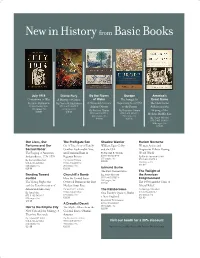

New in History from Basic Books

New in History from Basic Books July 1914 Divine Fury By the Rivers Europe America's Countdown to War A History of Genius of Water e Struggle for Great Game By Sean McMeekin By Darrin M. McMahon A Nineteenth-Century Supremacy, from 1453 e CIA’s Secret 978-0-465-03145-0 9 78-0-465-00325-9 Atlantic Odyssey to the Present Arabists and the 480 pages / hc 360 pages / hc By Erskine Clarke By Brendan Simms $29.99 $29.99 Shaping of the 978-0-465-00272-6 978-0-465-01333-3 Modern Middle East 488 pages / hc 720 pages / hc $29.99 $35.00 By Hugh Wilford 978-0-465-01965-6 384 pages / hc $29.99 Our Lives, Our The Profl igate Son Shadow Warrior Harlem Nocturne Fortunes and Our Or, A True Story of Family William Egan Colby Women Artists and Sacred Honor Con ict, Fashionable Vice, and the CIA Progressive Politics During e Forging of American and Financial Ruin in By Randall B. Woods World War II Independence, 1774-1776 Regency Britain 978-0-465-02194-9 By Farah Jasmine Griffi n 576 pages / hc By Nicola Phillips 978-0-465-01875-8 By Richard Beeman $29.99 978-0-465-02629-6 978-0-465-00892-6 264 pages / hc 528 pages / hc 360 pages / hc $26.99 $29.99 $28.99 Edmund Burke e First Conservative The Twilight of Bending Toward Churchill’s Bomb By Jesse Norman the American How the United States 978-0-465-05897-6 Justice 336 pages / hc Enlightenment e Voting Rights Act Overtook Britain in the First $27.99 e 1950s and the Crisis of and the Transformation of Nuclear Arms Race Liberal Belief American Democracy By Graham Farmelo The Rainborowes By George Marsden By Gary May 978-0-465-02195-6 One Family’s Quest to Build 978-0-465-03010-1 576 pages / hc 240 pages / hc 978-0-465-01846-8 a New England 336 pages / hc $29.99 $26.99 $28.99 By Adrian Tinniswood 978-0-465-02300-4 A Dreadful Deceit 384 pages / hc Heir to the Empire City e Myth of Race from the $28.99 New York and the Making of Colonial Era to Obama’s eodore Roosevelt America By Edward P. -

PIA 2363: International History Spring 2021 Thursdays, 12:10-3:05Pm, Zoom

PIA 2363: International History Spring 2021 Thursdays, 12:10-3:05pm, Zoom Professor: Ryan Grauer Office: 3932 Posvar Hall, but Zoom in reality Office Hours: Wednesdays and Thursdays, 3-5pm Email: [email protected] Phone: 412-624-7396 Course Description: Policymakers, scholars, analysts, journalists, average citizens, and others frequently talk about the “lessons of history” and what they mean for understanding, interpreting, and reacting to contemporary events in the international arena. For instance, when opening a newspaper (or a web- browser, or the Twitter app) on any given day, you are likely to be inundated with op-eds and think- pieces about how it is the 100th anniversary of X and the 50th anniversary of Y, and both events have profound implications for how we think about the world today. Sometimes, the authors of such pieces do have important insights to share. Other times, they confuse and muddle matters rather than clarify them. The variable utility of these bite-sized historical vignettes as aids for thinking about contemporary issues is not unique. Longer pieces of journalism, academic research, popular history books, and, most crucially, policymakers and those who work for them all frequently struggle to discern and apply whatever the appropriate lessons of history might be. This difficulty stems from the fact that learning the correct lessons is complicated. Nominally, history is the record of people and events preceding the current moment. Nominally, history is politically and ideologically neutral. In practice, however, history is neither of these things. In practice, history is the synthesized, and often stylized, reporting of certain people and certain events that some investigators have deemed worthy of study. -

David Greenberg

DAVID GREENBERG Professor of History Professor of Journalism & Media Studies Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey 4 Huntington Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 646.504.5071 • [email protected] Education. Columbia University, New York, NY. PhD, History. 2001. MPhil, History. 1998. MA, History. 1996. Yale University, New Haven, CT. BA, History. 1990. Summa cum laude. Phi Beta Kappa. Distinction in the major. Academic Positions. Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ. Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2016- . Associate Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2008-2016. Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism & Media Studies. 2004-2008. Appointment to the Graduate Faculty, Department of History. 2004-2008. Affiliation with Department of Political Science. Affiliation with Department of Jewish Studies. Affiliation with Eagleton Institute of Politics. Columbia University, New York, NY. Visiting Associate Professor, Department of History, Spring 2014. Yale University, New Haven, CT. Lecturer, Department of History and Political Science. 2003-04. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Cambridge MA. Visiting Scholar. 2002-03. Columbia University, New York, NY. Lecturer, Department of History. 2001-02. Teaching Assistant, Department of History. 1996-99. Greenberg, CV, p. 2. Other Journalism and Professional Experience. Politico Magazine. Columnist and Contributing Editor, 2015- The New Republic. Contributing Editor, 2006-2014. Moderator, “The Open University” blog, 2006-07. Acting Editor (with Peter Beinart), 1996. Managing Editor, 1994-95. Reporter-researcher, 1990-91. Slate Magazine. Contributing editor and founder of “History Lesson” column, the first regular history column by a professional historian in the mainstream media. 1998-2015. Staff editor, culture section, 1996-98. The New York Times. -

Recentering the United States in the Historiography of American Foreign Relations

The Scholar Texas National Security Review: Volume 3, Issue 2 (Spring 2020) Print: ISSN 2576-1021 Online: ISSN 2576-1153 RECENTERING THE UNITED STATES IN THE HISTORIOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN FOREIGN RELATIONS Daniel Bessner Fredrik Logevall 38 Recentering the United States in the Historiography of American Foreign Relations In the last three decades, historians of the “U.S. in the World” have taken two methodological turns — the international and transnational turns — that have implicitly decentered the United States from the historiography of U.S. foreign relations. Although these developments have had several salutary effects on the field, we argue that, for two reasons, scholars should bring the United States — and especially, the U.S. state — back to the center of diplomatic historiography. First, the United States was the most powerful actor of the post-1945 world and shaped the direction of global affairs more than any other nation. Second, domestic processes and phenomena often had more of an effect on the course of U.S. foreign affairs than international or transnational processes. It is our belief that incorporating the insights of a reinvigorated domestic history of American foreign relations with those produced by international and transnational historians will enable the writing of scholarly works that encompass a diversity of spatial geographies and provide a fuller account of the making, implementation, effects, and limits of U.S. foreign policy. Part I: U.S. Foreign Relations two trends that have emphasized the former rather After World War II than the latter. To begin with, the “international turn” (turn being the standard term among histo- The history of U.S. -

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS in LETTERS © by Larry James

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS IN LETTERS © by Larry James Gianakos Fiction 1917 no award *1918 Ernest Poole, His Family (Macmillan Co.; 320 pgs.; bound in blue cloth boards, gilt stamped on front cover and spine; full [embracing front panel, spine, and back panel] jacket illustration depicting New York City buildings by E. C.Caswell); published May 16, 1917; $1.50; three copies, two with the stunning dust jacket, now almost exotic in its rarity, with the front flap reading: “Just as THE HARBOR was the story of a constantly changing life out upon the fringe of the city, along its wharves, among its ships, so the story of Roger Gale’s family pictures the growth of a generation out of the embers of the old in the ceaselessly changing heart of New York. How Roger’s three daughters grew into the maturity of their several lives, each one so different, Mr. Poole tells with strong and compelling beauty, touching with deep, whole-hearted conviction some of the most vital problems of our modern way of living!the home, motherhood, children, the school; all of them seen through the realization, which Roger’s dying wife made clear to him, that whatever life may bring, ‘we will live on in our children’s lives.’ The old Gale house down-town is a little fragment of a past generation existing somehow beneath the towering apartments and office-buildings of the altered city. Roger will be remembered when other figures in modern literature have been forgotten, gazing out of his window at the lights of some near-by dwelling lifting high above his home, thinking