Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey Report

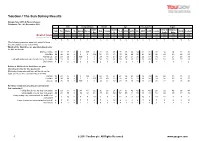

YouGov / The Sun Survey Results Sample Size: 2955 X Factor Viewers Fieldwork: 7th - 9th December 2011 Vote Voting intention Gender Age Social grade Region Little Under Rest of Midlands / Total Yes Maybe No Amelia Marcus Male Female 18-24 25-39 40-59 60+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland Mix 18 South Wales Weighted Sample 2960 364 615 1981 205 301 275 1105 1855 95 369 915 1036 546 1615 1345 361 924 628 808 239 Unweighted Sample 2955 338 603 2014 201 285 257 1053 1902 95 183 918 1226 533 1891 1064 428 907 598 787 235 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % [The following questions were only asked to those who are certain or may vote n=942] Which of the final three are you intending to vote for this weekend? Marcus Collins 31 38 27 0 0 100 0 31 31 26 35 26 34 34 31 31 37 34 24 32 26 Little Mix 28 26 29 0 0 0 100 21 33 23 33 36 24 18 27 30 28 29 29 28 21 Amelia Lily 21 23 20 0 100 0 0 27 17 23 17 20 21 25 23 17 16 17 21 23 31 I will wait and decide who to vote for on the night 19 11 23 0 0 0 0 19 18 26 15 16 20 22 18 20 18 18 23 17 19 Don't know 1 1 2 0 0 0 0 2 1 2 1 2 1 1 1 2 1 1 3 1 2 Rebased: Which of the final three are you intending to vote for this weekend? [Excluding those who said they will decide on the night, and those who said Don't know n=744] Marcus 39 43 35 0 0 100 0 40 38 35 41 32 43 44 38 39 46 42 33 38 33 Little Mix 35 30 39 0 0 0 100 27 40 32 39 44 31 23 33 38 34 36 39 34 27 Amelia 26 26 26 0 100 0 0 34 22 32 20 25 26 33 29 22 20 22 28 28 40 And how certain are you that you will vote for that contestant? I will definitely vote for that contestant 36 63 17 0 34 41 32 36 36 26 26 35 40 42 33 42 28 32 42 38 44 I will probably vote for that contestant 46 28 59 0 49 42 48 47 46 50 57 50 41 39 48 44 51 49 40 47 39 I may change my mind and vote for a different 9 5 12 0 9 9 10 9 9 6 11 9 9 11 12 6 13 11 8 8 7 contestant I may change my mind and not vote at all 8 3 11 0 7 7 9 7 8 18 6 6 8 8 7 9 7 8 9 6 10 Don't know 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 2 1 0 1 © 2011 YouGov plc. -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Sports Information Department • P. 0. Box 7399 • Austin, Texas 78713/7399 • (512) 471-7437

Sports Information Department • P. 0. Box 7399 • Austin, Texas 78713/7399 • (512) 471-7437 1 9 9 1 T E X A S R E L A Y S FINAL RESULTS OUTSTANDING TEAM •••••••••••••••• TCU MEN (winners in the 4x100 and 4x200-Meter Relays, plus shot put winner Jordy Feynolds) OUTSTANDING MALE PERFORMER ••..•. GORDON McKEE, unattached (set Texas Relays and Memorial Stadium long jump record 27-0 3/4) OUTSTANDING FEMALE PERFORMER .•.. STACY SWANK, San Antonio Texas Military Institute (winner of the High School C-irls 1600 meters and 3200 meters) l - . I RECORDS SET IN 1991 TEXAS RELAYS WOMEN'S 10,000-METER RUN 31:28.92 Francie-Larrieu Smith, New Balance (AMERICAN RECORD, breaking 31:35.3 by Mary Slaney, 1982) (TEXAS RELAYS RECORD, breaking 33:33.86 by Francie Larrieu-Smith, 1987) (MEMORIAL STADIUM RECORD, breaking 33:28.20 by Aileen O'Connor, Virginia, 198 MEN'S LONG JUMP 8.25/27-0 3/4 Gordon McKee, unattached (TEXAS RELAYS RECORD, breaking 26-9 3/4 by Chris Walker, Texas Southern ' (MEMORIAL STADIUM RECORD, breaking 26-11~ by Mike Conley, Arkansas 1985) WOMEN'S 3,000-METER RUN 9:13.3 Teena Colebrook, Nike Track Club (TEXAS RELAYS RECORD, breaking 9:21.3 by Angela Cook, Brigham Young 1987) REPTATHLON 6,020 Kym Carter, Oregon International (TEXAS RELAYS RECORD, breaking 5,828 by Eva Karblom, Brigham Young 1986) JUNIOR COLLEGE SPRINT MEDLEY RELAY 3-:13.25 Barton County (David Oaks, Wes Russell, Marlin Cannon, Bobby Gaseitsiwe) (NATIONAL JUNIOR COLLEGE RECORD, breaking 3:14.44 by Taft (CA) 1989 (TEXAS RELAYS RECOFn, breaking 3:17.15 by Odessa 1989) JUNIOR COLLEGE 4x800-METER RELAY 7:25.04 South Plains (David Singoei, Joseph Tengelie, Diego Cordoba, Phillimon Hanneck) (TEXAS RELAYS RECORD, breaking 7:25.10 by Blinn 1987) - , 1991 TEXAS RELAYS April 6 COLLEGIATE HEN 100-METER DASH FINAL Wind +1.00 1. -

BEACH BOYS Vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music

The final word on the Beach Boys versus Beatles debate, neglect of American acts under the British Invasion, and more controversial critique on your favorite Sixties acts, with a Foreword by Fred Vail, legendary Beach Boys advance man and co-manager. BEACH BOYS vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music Buy The Complete Version of This Book at Booklocker.com: http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/3210.html?s=pdf BEACH BOYS vs Beatlemania: Rediscovering Sixties Music by G A De Forest Copyright © 2007 G A De Forest ISBN-13 978-1-60145-317-4 ISBN-10 1-60145-317-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Printed in the United States of America. Booklocker.com, Inc. 2007 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY FRED VAIL ............................................... XI PREFACE..............................................................................XVII AUTHOR'S NOTE ................................................................ XIX 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD 1 2. CATCHING A WAVE 14 3. TWIST’N’SURF! FOLK’N’SOUL! 98 4: “WE LOVE YOU BEATLES, OH YES WE DO!” 134 5. ENGLAND SWINGS 215 6. SURFIN' US/K 260 7: PET SOUNDS rebounds from RUBBER SOUL — gunned down by REVOLVER 313 8: SGT PEPPERS & THE LOST SMILE 338 9: OLD SURFERS NEVER DIE, THEY JUST FADE AWAY 360 10: IF WE SING IN A VACUUM CAN YOU HEAR US? 378 AFTERWORD .........................................................................405 APPENDIX: BEACH BOYS HIT ALBUMS (1962-1970) ...411 BIBLIOGRAPHY....................................................................419 ix 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD Rock is a fickle mistress. -

2019 "BET Awards" to Honor Grammy Award Winning and Oscar-Nominated Actress Mary J

2019 "BET Awards" To Honor Grammy Award Winning And Oscar-Nominated Actress Mary J. Blige With Prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award June 12, 2019 REGINA HALL WILL HOST THE 19TH ANNUAL AWARDS SHOW AIRING LIVE ON SUNDAY, JUNE 23 FROM MICROSOFT THEATER IN LOS ANGELES AT 8PM ET #BETAWARDS NEW YORK, June 12, 2019 /PRNewswire/ -- Today BET Networks announces Grammy Award-winning singer, songwriter, Oscar-nominated actress and philanthropist, Mary J. Blige will be honored with the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award at the 19th annual "BET Awards." The 2019 "BET Awards" will air LIVE on Sunday, June 23 at 8pm ET from the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles, CA on BET. With a career of landmark achievements including eight multi-platinum albums, nine Grammy Awards (plus a staggering 32 nominations), two Academy Award nominations, two Golden Globe nominations, and a SAG nomination, Mary J. Blige has remained a figure of inspiration, transformation and empowerment making her one of the defining voices of the contemporary music era and cemented herself as a global superstar. And in the ensuing years, the singer/songwriter has attracted an intensely loyal fan base—responsible for propelling worldwide sales of more than 50 million albums. She began moving people with her soulful voice at the age of 18 when she became Uptown Records youngest and first female artist. Over the years, Blige has helped redefine R&B in the contemporary music era with chart-topping hits like "Be Without You", "No More Drama" and "Family Affair." At the 2018 Academy Awards, Blige made history as the first double nominee across the acting and music categories for Best Song and Best Supporting Actress for her work on Mudbound. -

Past Forward 37

Issue No. 37 July – November 2004 Produced1 by Wigan Heritage Service FREE From the Editor Retirement at the History Shop This edition of Past Forward reflects BARBARA MILLER, Heritage Assistant, manner. If she could not answer your the many exciting things which are retired on 6 June. It was a memorable query herself, she always knew going on in the Heritage Service at day for her. Not only was it the someone who could. the moment. There is an excellent beginning of a new and exciting stage Barbara joined the then Wigan exhibition programme for the rest of in her life, but also her 60th birthday (I Museum Service at Wigan Pier in 1985 the year, for example, as you will see am sure she will not mind that and, I am glad to say, remained with us – and our new exhibition leaflet will revelation!) and of course, she was a through our transformation into Wigan be out very soon. You can also read ‘D’ Day baby! Heritage Service and the development about the increasing range of Many of you will have met her on of the History Shop. In the past, she not the reception desk at the History Shop, only undertook a variety of clerical ventures in which our Friends have and been impressed by her duties for us, but also spent many been engaged. knowledgeable, friendly and efficient hours working on the museum I would draw your attention to collections, helping to make them more the questionnaire which appears in accessible. this issue – designed as a pull-out On her last day at work, we all had insert, as I know many of you a good laugh reminiscing about old treasure your copies of Past Forward, times. -

Kappale Artisti

14.7.2020 Suomen suosituin karaokepalvelu ammattikäyttöön Kappale Artisti #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #Selˆe The Chainsmokers #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat Justin Bieber #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderˆnger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Can't Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again LTD (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The W England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & The Diamonds (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones (I Could Only) Whisper Your Name Harry Connick, Jr (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (It Looks Like) I'll Never Fall In Love Again Tom Jones (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life (Duet) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Re˜ections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Marie's The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty KC And The Sunshine Band (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (Theme From) New York, New York Frank Sinatra (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) The Beastie Boys 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Coeurs Debout Star Academie 2009 1000 Miles H.E.A.T. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

The Art of Regeneration: the Establishment and Development of the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology, 1985–2010

The Art of Regeneration: the establishment and development of the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology, 1985–2010 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jane Clayton School of Architecture, University of Liverpool August 2012 iii Abstract The Art of Regeneration: the establishment and development of the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology, 1985-2010 Jane Clayton This thesis is about change. It is about the way that art organisations have increasingly been used in the regeneration of the physical environment and the rejuvenation of local communities, and the impact that this has had on contemporary society. This historical analysis of the development of a young art organisation, the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology (FACT), which has previously not been studied in depth, provides an original contribution to knowledge with regard to art and culture, and more specifically the development of media and community art practices, in Britain. The nature of FACT’s development is assessed in the context of the political, socio- economic and cultural environment of its host city, Liverpool, and the organisation is placed within broader discourses on art practice, cultural policy, and regeneration. The questions that are addressed – of local responsibility, government funding and institutionalisation – are essential to an understanding of the role that publicly funded organisations play within the institutional framework of society, without which the analysis of the influence of the state on our cultural identity cannot be achieved. The research was conducted through the triangulation of qualitative research methods including participant observation, in-depth interviews and original archival research, and the findings have been used to build upon the foundations of the historical analysis and critical examination of existing literature in the fields of regeneration and culture, art and media, and museum theory and practice. -

IL Combo Ndx V2

file IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE The Quarterly Journal of THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE SOCIETY COMBINED INDEX of Volumes 1 to 7 1976 – 1996 IL No.1 to No.79 PROVISIONAL EDITION www.industrial-loco.org.uk IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 INTRODUCTION and ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This “Combo Index” has been assembled by combining the contents of the separate indexes originally created, for each individual volume, over a period of almost 30 years by a number of different people each using different approaches and methods. The first three volume indexes were produced on typewriters, though subsequent issues were produced by computers, and happily digital files had been preserved for these apart from one section of one index. It has therefore been necessary to create digital versions of 3 original indexes using “Optical Character Recognition” (OCR), which has not proved easy due to the relatively poor print, and extremely small text (font) size, of some of the indexes in particular. Thus the OCR results have required extensive proof-reading. Very fortunately, a team of volunteers to assist in the project was recruited from the membership of the Society, and grateful thanks are undoubtedly due to the major players in this exercise – Paul Burkhalter, John Hill, John Hutchings, Frank Jux, John Maddox and Robin Simmonds – with a special thankyou to Russell Wear, current Editor of "IL" and Chairman of the Society, who has both helped and given encouragement to the project in a myraid of different ways. None of this would have been possible but for the efforts of those who compiled the original individual indexes – Frank Jux, Ian Lloyd, (the late) James Lowe, John Scotford, and John Wood – and to the volume index print preparers such as Roger Hateley, who set a new level of presentation which is standing the test of time. -

Bill Harry. "The Paul Mccartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970

Bill Harry. "The Paul McCartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970 BILL HARRY. THE PAUL MCCARTNEY ENCYCLOPEDIA Tadpoles A single by the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, produced by Paul and issued in Britain on Friday 1 August 1969 on Liberty LBS 83257, with 'I'm The Urban Spaceman' on the flip. Take It Away (promotional film) The filming of the promotional video for 'Take It Away' took place at EMI's Elstree Studios in Boreham Wood and was directed by John MacKenzie. Six hundred members of the Wings Fun Club were invited along as a live audience to the filming, which took place on Wednesday 23 June 1982. The band comprised Paul on bass, Eric Stewart on lead, George Martin on electric piano, Ringo and Steve Gadd on drums, Linda on tambourine and the horn section from the Q Tips. In between the various takes of 'Take It Away' Paul and his band played several numbers to entertain the audience, including 'Lucille', 'Bo Diddley', 'Peggy Sue', 'Send Me Some Lovin", 'Twenty Flight Rock', 'Cut Across Shorty', 'Reeling And Rocking', 'Searching' and 'Hallelujah I Love Her So'. The promotional film made its debut on Top Of The Pops on Thursday 15 July 1982. Take It Away (single) A single by Paul which was issued in Britain on Parlophone 6056 on Monday 21 June 1982 where it reached No. 14 in the charts and in America on Columbia 18-02018 on Saturday 3 July 1982 where it reached No. 10 in the charts. 'I'll Give You A Ring' was on the flip.