The Impact of the Veoh Litigations on Viacom V. Youtube, 10 N.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UMG V Veoh 9Th Opening Brief.Pdf

Case: 09-56777 04/20/2010 Page: 1 of 100 ID: 7308924 DktEntry: 11-1 No. 09-56777 ____________ IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT ___________________ UMG RECORDINGS, INC.; UNIVERSAL MUSIC CORP.; SONGS OF UNIVERSAL, INC.; UNIVERSAL-POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING, INC.; RONDOR MUSIC INTERNATIONAL, INC.; UNIVERSAL MUSIC—MGB NA LLC; UNIVERSAL MUSIC—Z TUNES LLC; UNIVERSAL MUSIC—MBG MUSIC PUBLISHING LTD., Plaintiffs-Appellants v. VEOH NETWORKS, INC., Defendant-Appellee. _______________________________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California, Western Division—Los Angeles Honorable A. Howard Matz, District Judge __________________________________ APPELLANTS’ BRIEF _____________________________________ Steven Marenberg, Esq. State Bar No. 101033 Brian Ledahl, Esq. State Bar No. 186579 Carter Batsell State Bar No. 254396 IRELL & MANELLA, LLP 1800 Avenue of the Stars Suite 900 Los Angeles, California 90067 Telephone: (310) 277-1010 Facsimile: (310) 203-7199 ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANTS 2221905 Case: 09-56777 04/20/2010 Page: 2 of 100 ID: 7308924 DktEntry: 11-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT................................................ 2 JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT ................................................................. 3 ISSUES PRESENTED ..................................................................................... 4 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........................................................................ 6 FACTS ........................................................................................................... -

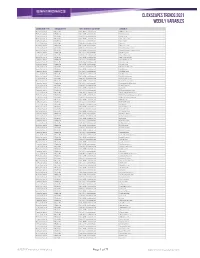

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Investigating the Network Characteristics of Two Popular Web-Based Video Streaming Sites

European Scientific Journal November 2017 edition Vol.13, No.33 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Investigating the Network Characteristics of Two Popular Web-Based Video Streaming Sites Dr. Feras Mohammed Almatarneh University of Tabuk Department of Computer Science, College Duba Saudi Arabia Doi: 10.19044/esj.2017.v13n33p305 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2017.v13n33p305 Abstract The determinants of the strategies to be employed by video streaming sites are application (mobile devices or web browsers) and container of the video application. They affect video streaming network characteristics, which is often the traffic flow, and its quality. It is against this background that studies on streaming strategies suggested the need to investigate and identify the relationship between buffer time, video stream protocol, packet speed and size, upload time, and waiting period, specifically to aid network administrative support in case of network traffic bottlenecks. In view of this, this study investigates the network characteristics of YouTube and Vimeo, using experimental methodology, and involving WireShark as network analyzer. Google Chrome and Firefox are the web browsers employed, while packet size, protocols, packet interval, TCP window size and accumulation ratio are the metrics. Short ON-OFF, Long ON-OFF, and No ON-OFF cycles are the three streaming strategies identified. It is further shown that both Vimeo and YouTube employ these strategies but the choice depends on the container of the video streamed. Keywords: Network characteristics, streaming strategies, video streaming sites, traffic flow Introduction Video streaming is one of the techniques for video distribution over the internet. It helps in lecture and news broadcast, and allows users’ access, without any geographical constraints (Karki, Seenivasan, Claypool, & Kinicki, 2010; Tan & Zakhor, 1999). -

Watch Deadman Wonderland Online

1 / 2 Watch Deadman Wonderland Online Bloody Hell—this is what Deadman Wonderland literally is! ... List of Elfen Lied episodes Very rare Lucy/Nyu & Nana figures from Elfen Lied. ... Dream Tech Series Elfen Lied Lucy & Nyu figures with extra faces set. at the best online prices at …. Watch Deadman Wonderland online animestreams. Other name: デッドマン・ワンダーランド. Plot Summary: Ganta Igarashi has been convicted of a crime that .... AnimeHeaven - watch Deadman Wonderland OAD (Dub) - Deadman Wonderland OVA (Dub) Episode anime online free and more animes online in high quality .... Deadman wonderland episode 1 english dubbed. Deadman . Crunchyroll deadman wonderland full episodes streaming online for free.Dead man wonderland .... Watch Deadman Wonderland 2011 full Series free, download deadman wonderland 2011. Stars: Kana Hanazawa, Greg Ayres, Romi Pak.. BOOK ONLINE. Kids go free before 12 ... Pledge your love as your nearest and dearest watch, with the Canadian Rockies as your witness. Then, head inside for .... [ online ] Available http://csii.usc.edu/documents/Nationalisms of and against ... ' Deadman Wonderland .... Nov 2, 2020 — This show received positive comments from the viewers. However, does it mean there will be a second season? Gandi Baat 5 All Episodes Free ( watch online ) #gandi_baat #webseries tags ... Watch Deadman Wonderland Online English Dubbed full episodes for Free.. Best anime series you can watch in 2021 Apr 09, 2014 · 1st 2 Berserk Films Stream on Hulu for 1 Week. Berserk: The ... Deadman Wonderland (2011). Ganta is .... 2 hours ago — Just like Sword Art Online these 5 are ... 1 year ago. 1,252,109 views. Why DEADMAN WONDERLAND isn't getting a Season 2. -

Gimme-Shelter-Complete-LR.Pdf

Case: 09-55902 12/20/2011 ID: 8006118 DktEntry: 39-1 Page: 1 of 49 FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT UMG RECORDINGS, INC., a Delaware corporation; UNIVERSAL MUSIC CORP., a New York corporation; SONGS OF UNIVERSAL, INC., a California corporation; UNIVERSAL-POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING, INC., a Delaware corporation; RONDOR MUSIC INTERNATIONAL, INC., a California corporation; UNIVERSAL MUSIC-MGB NA LLC, a California Limited Liability Company; UNIVERSAL MUSIC-Z TUNES LLC, a New York Limited Liability Company; UNIVERSAL MUSIC-MBG MUSIC PUBLISHING LTD., a UK Company, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. SHELTER CAPITAL PARTNERS LLC, a Delaware Limited Liability Company; SHELTER VENTURE FUND LP, a Delaware Limited Partnership; SPARK CAPITAL LLC, a Delaware Limited Liability Company; SPARK CAPITAL, L.P., a Delaware Limited Partnership; 21055 Case: 09-55902 12/20/2011 ID: 8006118 DktEntry: 39-1 Page: 2 of 49 21056 UMG RECORDINGS v. SHELTER CAPITAL PARTNERS TORNANTE COMPANY, LLC, a Delaware Limited Liability Company, No. 09-55902 Defendants-Appellees, D.C. No. and 2:07-cv-05744- VEOH NETWORKS, INC., a California AHM-AJW corporation, Defendant. UMG RECORDINGS, INC., a Delaware corporation; UNIVERSAL MUSIC CORP., a New York corporation; SONGS OF UNIVERSAL, INC., a California corporation; UNIVERSAL-POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING, INC., a Delaware corporation; RONDOR MUSIC INTERNATIONAL, INC., a California corporation; UNIVERSAL MUSIC-MGB NA LLC, a California Limited Liability Company; UNIVERSAL MUSIC-Z TUNES LLC, a New York Limited Liability Company; UNIVERSAL MUSIC-MBG MUSIC PUBLISHING LTD., a UK Company, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. VEOH NETWORKS, INC., a California corporation, Defendant-Appellee, Case: 09-55902 12/20/2011 ID: 8006118 DktEntry: 39-1 Page: 3 of 49 UMG RECORDINGS v. -

Cloud TV Munich-S-Version 2017.Pptx

6/8/17 Into the 3rd Generaon of Presentaon Outline Video: Cloud TV • 1. 3rd Generaon TV--Overview • 2. Media Industry Structure of 3rd Generaon TV – Content Creators Eli Noam – Content Online Aggregators Columbia University, Columbia – Cloud Plaorms Ins9tute for Tele-Informaon – Content Distribu9on Networks – Internet Service Providers/Transmission Networks Speaker Background Notes – Consumer Devices • 3. Policy and Societal Issues of 3rd Munich 2017 1 Generaon TV • This presentaon is about television. • It is therefore important to understand that • But it iss really much more than that we are on the verge of one of humanity’s • There are few ques9ons with more long-term greatest leaps in media communicaons, and implicaons than the way we shape our consequently also of one of its major communicaons system. disrup9ons of social, cultural, poli9cal, and • If the medium is indeed the message, and if these economic arrangements. messages influence people and ins9tu9ons, then tomorrow’s media, and today’s media policies, will govern future society, culture, and economy. • Television has come a long way, and has an • If Moore’s law is a rate of change of about even longer way to go. 40% a year for the IT sector, , then the what • What runs through its history is myopia. we can call Sarnoff’s 2nd law , aer David • In each of its generaons, most users did not Sarnoff, head of RCA a for decades, would be perceive a need for anything more advanced about 4% per year. X than they already had. • And in each of these generaons people did not eXpect the impact of the new medium when it emerged -- by a wide margin. -

Can You Download Stuff from Hulu App Hulu Desktop for Windows

can you download stuff from hulu app Hulu Desktop for Windows. Hulu Desktop is a content streaming platform that lets you watch movies, TV shows, videos, anime, and live TV. The software has been designed for Windows and contains various features that make streaming via a laptop or desktop quite seamless. The app is free to download. However, you have to purchase a subscription to start streaming. Hulu download is currently available in the US and offers a 30-day trial period. What is Hulu Desktop? Hulu Desktop is a video streaming platform that offers a library of content across multiple genres. Similar to platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, it gives users Hulu original shows and movies, live TV, documentaries, anime, and more. Owned by The Walt Disney Company, Hulu offers various subscription options and is also available as a bundle with Disney streaming service. What can I expect from the interface of Hulu? When you complete the Hulu Desktop download , you come across a simple and clean interface that makes watching shows and movies a pleasant experience. The intuitive dashboard features a menu with several settings, volume buttons, playback controls, and more. It also consists of a comprehensive Help section that has answers to all user queries. You can also use the platform to create multiple profiles and stream content from different devices. The app also has a search bar that lets you easily find any program or film that you wish to watch . Since the search is predictive, you’ll be able to locate the file you want to stream without having to even type its entire name. -

URGENT! PLEASE DELIVER Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101

URGENT! PLEASE DELIVER www.cablefaxdaily.com, Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101 5 Pages Today Friday — May 15, 2009 Volume 20 / No. 092 Get It Right: Former FCC Heads Weigh In on Broadband Policy No matter where they sit on the political spectrum, panelists at Free Press’ “Changing Media” Summit in DC agreed that the country’s broadband policy is a big deal. Putting together the plan, on which the FCC is taking comments until June 8, is another matter. “National broadband policy should be in the office of the President, not at the FCC,” former FCC chmn Michael Powell said. His reasoning is that broadband will be key in solving national problems—health care, the economy, etc. Powell, a Republican and Bush nominee, argued that the previous administration never committed to a broadband policy. “I’m much more encouraged that our current president speaks of it, but I think it being developed inside a regulatory agency is fundamentally a mistake,” he said, complaining that the FCC is saddled with a severe amount of regulatory restraint. Another former FCC chmn at the summit, Clinton appointee Reed Hundt, also stressed the signifi cance of upcoming broadband decisions. “In my view, the biggest single impact on future communications in America consist of the choice made by Commerce and the Dept of Agriculture on spending of the broadband stimulus,” he said. Meanwhile, Hundt called a myth the notion that the $7.2bln in funds provided for broadband stimulus are insuf- fi cient. If the money is divided into tiny little grants with no coordinated purpose, then no, it doesn’t go far, he said—but done right, “this is more than enough to completely alter the structure of broadband in America for 50 years.” For ex- ample, if used for loan guarantees, the $7.2bln would represent $70bln, which would mean $140bln in new cap ex, he said. -

Free Internet Tv Watch

Free internet tv watch click here to download Free TV. More than channels from around the world. News, Music, Business,Sport. Watch free online TV stations from all over the world. Find the best free Internet TV, and live web TV on Streema. How to watch TV online for free with these sites, including Hulu, Veoh, Daily, and Sidereel. Find news, sports, movies, and lots more. WWITV: World Wide Internet TV Your Portal to watch free live online TV broadcasts. Thank you for visiting the World Wide Internet TV website (wwiTV). No money in the budget for a cable subscription? Or even for Hulu? Fear not: As long as you've got internet, you can enjoy a wealth of free TV. Watch live TV from the BBC, ITV, Channel 4, Five, Dave and other UK channels on TVPlayer online for FREE. TV on your laptop, smart phone, tablet, smart TV or Xbox. IOS, Android, Windows mobile TV apps. Over TV channels. Watch TV free with Zattoo Internet TV. Watch Free Internet TV Stations from around the world on your computer. Over Free online TV channels. Large collection of live Web TV stations. Find quickly and easily live TV channels on the Internet. Watch TV Broadcasts from USA, India, Europe & all other countries on your PC / MAC, Phone, or Tablet . Tue 10/23 PM. pm pm; pm pm; pm pm; pm pm; pm pm. Now. © Copyright Pluto TV; Privacy Policy. Watch free TV and movies on your Android Phone and Android TV. Pluto TV has over live channels and 's of movies from the biggest names like: NBC. -

Supported Sites

# Supported sites - **1tv**: Первый канал - **1up.com** - **20min** - **220.ro** - **22tracks:genre** - **22tracks:track** - **24video** - **3qsdn**: 3Q SDN - **3sat** - **4tube** - **56.com** - **5min** - **6play** - **8tracks** - **91porn** - **9c9media** - **9c9media:stack** - **9gag** - **9now.com.au** - **abc.net.au** - **abc.net.au:iview** - **abcnews** - **abcnews:video** - **abcotvs**: ABC Owned Television Stations - **abcotvs:clips** - **AcademicEarth:Course** - **acast** - **acast:channel** - **AddAnime** - **ADN**: Anime Digital Network - **AdobeTV** - **AdobeTVChannel** - **AdobeTVShow** - **AdobeTVVideo** - **AdultSwim** - **aenetworks**: A+E Networks: A&E, Lifetime, History.com, FYI Network - **afreecatv**: afreecatv.com - **afreecatv:global**: afreecatv.com - **AirMozilla** - **AlJazeera** - **Allocine** - **AlphaPorno** - **AMCNetworks** - **anderetijden**: npo.nl and ntr.nl - **AnimeOnDemand** - **anitube.se** - **Anvato** - **AnySex** - **Aparat** - **AppleConnect** - **AppleDaily**: 臺灣蘋果⽇報 - **appletrailers** - **appletrailers:section** - **archive.org**: archive.org videos - **ARD** - **ARD:mediathek** - **Arkena** - **arte.tv** - **arte.tv:+7** - **arte.tv:cinema** - **arte.tv:concert** - **arte.tv:creative** - **arte.tv:ddc** - **arte.tv:embed** - **arte.tv:future** - **arte.tv:info** - **arte.tv:magazine** - **arte.tv:playlist** - **AtresPlayer** - **ATTTechChannel** - **ATVAt** - **AudiMedia** - **AudioBoom** - **audiomack** - **audiomack:album** - **auroravid**: AuroraVid - **AWAAN** - **awaan:live** - **awaan:season** -

Jetaa Winter 2009 Draft 5 Full.Qxp

WINTER 2009 JETAANY.ORG/MAGAZINE 1 3 Letter From the Editor / Letter From the President 4 Nippon News Blotter 5 JETAAnnouncements 6 East Meets West 7 Nihonjin in New York Featuring the JLGC By Junko Ishikawa 8 JETlog Featuring Sean Sakamoto 9 JetWit.com Q&A with Steven Horowitz 9 Catching Up with Randall David Cook By Lyle Sylvander 10 Youth for Understanding By Sylvia Pertzborn 11 Theatre Review: Shogun Macbeth / John Briggs Q&A By Olivia Nilsson and Adren Hart 12 Speekit LLC: Kevin Kajitani Interview By Junko Ishikawa 13 Jero: The JQ Interview By Justin Tedaldi 14 Joost!: Japanese TV on Your PC By Rick Ambrosio 15 Film Review: Sukiyaki Western Django By Elizabeth Wanic 16 An Inside Look at Japan Airlines By Kelly Nixon 17 Japan Society’s Best of Tora-san Series By Matt Matysik 18 Chip Kidd Talks Bat-Manga! By Justin Tedaldi 19 Book Corner: Natuso Kirino’s Real World By David Kowalsky 19 Restaurant Spotlight: Wajima By Allen Wan 20 Adventures in SwirlySwirlDates By Rick Ambrosio and Nicole Bongiorno 21 Yosakoi Dance Project By Kirsten Phillips 22 The Tale of Eric and Ozawa By Rick Ambrosio 23 Top 14 List / Next Issue / Sponsors Index While it’s not a new chibi-Escalade, we’ve awarded some pretty spiffy prizes to the winners of our “new” anecdote contest. Therese Stephen (Iwate-ken, 1996-99) Dinner for two at Bao Noodles (www.baonoo- dles.com), owned by Chris Johnson (Oita-ken, 1992-95), 2nd Ave. between 22nd & 23rd Sts. Rick Ambrosio (Ibaraki-ken, 2006-08) $25 Gift Certificate at Kinokuniya Bookstore, 1071 Avenue of the Americas Meredith Hodges-Boos (Ehime-ken, 2003-05) One item with free delivery at Waltzing Matilda’s NYC (waltzingmatildasnyc.com), an Aussie- style bakery owned by Laura Epstein (Gunma- ken, 2001-02) Andecdotes start on page 8. -

Can We Download Movies from Pluto Tv -App

can we download movies from pluto tv -app ViacomCBS’ Pluto TV Sets Spain, France, Italy Launches, Seals Movistar Plus Deal (EXCLUSIVE) Revving up its streaming service expansion in Europe, ViacomCBS will launch leading AVOD service Pluto TV in Spain from the end of October. It will then roll out Pluto TV in France and Italy in 2021, the French launch being set for first quarter 2021, ViacomCBS Networks Intl. revealed Thursday. Coming less than a month after the announcement of the rebranding of CBS All Access as Paramount Plus, an expanded streaming service set to debut early next year, the new European roll-out shows ViacomCBS ramping up ever more its OTT services in and outside the U.S. Compared with the U.S., Europe is more of a challenge for AVOD due to market fragmentation. The deal for Spain, however, shows ViacomCBS allying from the get-go with the market’s biggest content investor, pay TV Movistar Plus for an ad-sales alliance. In line with other territories, Pluto TV will bow in Spain via pluto.tv, Apple TV, Android TV, and Amazon Fire TV, as well as mobile device apps for download in iOS and Android. The Spanish platform will offer 40 thematic channels and thousands of hours of free content across different genres such as movies, series, reality, kids’ IP, lifestyle, crime, and comedy, working with more than 20 content partners in Spain, such as All3Media, Banijay, Fremantle and Lionsgate. The partnership with Movistar Plus, the Spanish pay TV division of giant European telco Telefonica, will see Movistar Plus selling Pluto TV’s conventional advertising in Spain.