150 Votes for Women Book.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Panel Systems Catalog

Table of Contents Page Title Page Number Terms and Conditions 3 - 4 Specifications 5 2.0 and SB3 Panel System Options 16 - 17 Wood Finish Options 18 Standard Textile Options 19 2.0 Paneling System Fabric Panel with Wooden Top Cap 6 - 7 Fabric Posts and Wooden End Caps 8 - 9 SB3 Paneling System Fabric Panel with Wooden Top Cap 10 - 11 Fabric Posts with Wooden Top Cap 12 - 13 Wooden Posts 14 - 15 revision 1.0 - 12/2/2020 Terms and Conditions 1. Terms of Payment ∙Qualified Customers will have Net 30 days from date of order completion, and a 1% discount if paid within 10 days of the invoice date. ∙Customers lacking credentials may be required down payment or deposit in full prior to production. ∙Finance charges of 2% will be applied to each invoice past 30 days. ∙Terms of payment will apply unless modified in writing by Custom Office Design, Inc. 2. Pricing ∙All pricing is premised on product that is made available for will call to the buyer pre-assembled and unpackaged from our base of operations in Auburn, WA. ∙Prices subject to change without notice. Price lists noting latest date supersedes all previously published price lists. Pricing does not include A. Delivery, Installation, or Freight-handling charges. B. Product Packaging, or Crating charges. C. Custom Product Detail upcharge. D. Special-Order/Non-standard Laminate, Fabric, Staining and/or Labor upcharge. E. On-site service charges. F. Federal, state or local taxes. 3. Ordering A. All orders must be made in writing and accompanied with a corresponding purchase order. -

Historic Ivinson Mansion Historic Ivinson Mansion Laramie Plains Museum from Those Newsletter

A Bewitching View of Laramie High School in 1952 Historic Ivinson Mansion Historic Ivinson Mansion Laramie Plains Museum from those Newsletter Laramie Plains Museum whooooo know The Historic Ivinson Mansion Laramie Plains Museum Newsletter Friday, Oct. 25 FALL 2019 NEWSLETTER is published 4 times a year by the 7:00pm Laramie Plains Museum Association Sunday, Oct. 27 603 East Ivinson Avenue 3:00pm Laramie, WY 82070 Friday, November 1 Phone: 307-742-4448 All performances are at 7:00pm the Van Oss Stage, Sunday, November 3 [email protected] Alice Hardie Stevens 3:00pm Web site: www.laramiemuseum.org Event Center, Laramie Plains Museum Children 12 & Under $5.00 603 East Ivinson Managing Editor & Graphic Design Laramie, WY Advance Tickets Mary Mountain at these locations: Written and Directed by carole homer Contributing Reporters Carriage House Gifts & Office behind the Ivinson Mansion Karen Bard First Interstate Bank Elizabeth Davis Musical direction by susan shumway 211 Ivinson Wyoming Tourism Press Eppson Center for Seniors 1560 N. 3rd Mary Mountain Kim Viner Photographers Joyce Powell Danny Walker Jason Roesler Assistance to the Editor Amy Allen Crystal Griffis Stan Gibson In this year of the Wyoming Woman we remember Nonprofit Org. Send changes of address to that in 1908, Mayor Markbreit of Cincinnati, Ohio Laramie Plains Museum U.S. Postage Paid 603 E. Ivinson Avenue declared that women are physically unfit to operate Laramie, WY 82070 an automobile. Permit No. 23 [email protected] RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED Evening at the Ivinsons’ 2019 was a perfect finishing touch to a busy, captivating summer season: Victorian Teas, Weddings, Receptions, Marry Me in Laramie, Art Fest, Downey Days, Suffrage coverage, teens leading tours of the Ivinson Mansion and a Museum complex that continues to shine in myriad ways. -

Report on the Draft Investigatory Powers Bill

Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament Report on the draft Investigatory Powers Bill Chair: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament Report on the draft Investigatory Powers Bill Chair: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 3 of the Justice and Security Act 2013 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 9 February 2016 HC 795 © Crown copyright 2016 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us via isc.independent.gov.uk/contact Print ISBN 9781474127714 Web ISBN 9781474127721 ID 26011601 02/16 53894 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office THE INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMITTEE OF PARLIAMENT The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP (Chair) The Rt. Hon. Sir Alan Duncan KCMG MP The Rt. Hon. Fiona Mactaggart MP The Rt. Hon. George Howarth MP The Rt. Hon. Angus Robertson MP The Rt. Hon. the Lord Janvrin GCB GCVO QSO The Rt. -

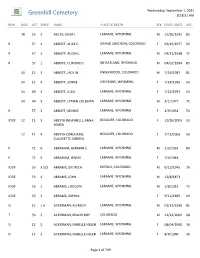

Greenhill Web Listing

Wednesday, September 1, 2021 Greenhill Cemetery 8:18:31 AM ROW BLOC LOT SPACE NAME PLACE OF DEATH SEX DEATH_DATE AGE 78 55 2 AALTO, EVOR J LARAMIE, WYOMING M 12/26/1995 85 R 57 4 ABBOTT, ALICE E. GRAND JUNCTION, COLORADO F 03/15/1977 66 R 57 2 ABBOTT, ALLEN C. LARAMIE, WYOMING M 04/11/1938 71 R 57 1 ABBOTT, CLIFFORD J. WHEATLAND, WYOMING M 04/02/1994 85 34 12 3 ABBOTT, JACK W. ENGLEWOOD, COLORADO M 7/26/1987 81 34 12 4 ABBOTT, JENNIE CHEYENNE, WYOMING F 7/24/1959 54 34 49 4 ABBOTT, JULIA LARAMIE, WYOMING F 7/21/1957 54 34 49 3 ABBOTT, LYMAN COLEMAN LARAMIE, WYOMING M 3/1/1977 71 R 57 3 ABBOTT, MINNIE LARAMIE, WYOMING F 2/9/1932 54 IOOF 12 11 3 ABEYTA (MUNNELL), ANNA BOULDER, COLORADO F 12/26/2003 53 MARIA 12 11 4 ABEYTA-CORCHADO, BOULDER, COLORADO F 7/13/2006 56 CLAUDETTE ANDREA P 72 6 ABRAHAM, HERMAN E. LARAMIE, WYOMING M 2/3/1962 84 P 72 5 ABRAHAM, JENNIE LARAMIE, WYOMING F 7/4/1948 IOOF 53 3 1/2 ABRAMS, DIETRICH PUEBLO, COLORADO M 9/12/1945 76 IOOF 53 4 ABRAMS, JOHN LARAMIE, WYOMING M 11/8/1873 IOOF 53 1 ABRAMS, LUDOLPH LARAMIE, WYOMING M 1/8/1913 72 IOOF 53 2 ABRAMS, SOPHIA F 9/12/1895 49 O 12 1 A ACKERMAN, ALFRED F LARAMIE, WYOMING M 01/13/1996 81 T 56 5 ACKERMAN, EDWIN ROY COLORADO M 11/22/2002 68 O 12 2 ACKERMAN, ISABELLE HELEN LARAMIE, WYOMING F 08/04/1960 36 O 12 2 ACKERMAN, ISABELLE HELEN LARAMIE, WYOMING F 8/4/1960 36 Page 1 of 749 ROW BLOC LOT SPACE NAME PLACE OF DEATH SEX DEATH_DATE AGE L 66 5 ACKERMAN, JACK ALLEN LARAMIE, WYOMING M 7/4/1970 20 T 56 8 ACKERMAN, ROY FRANCIS LARAMIE, WYOMING M 2/27/1936 51 O 12 1 ACKERMAN, RUDOLPH LARAMIE, WYOMING M 10/10/1951 35 HENRY O 60 2 ACKERSON, JAMES R. -

Victor Jenkins CDG., CSA FILM PRODUCTION COMPANY DIRECTOR / PRODUCER

Victor Jenkins CDG., CSA FILM PRODUCTION COMPANY DIRECTOR / PRODUCER THE SECRET LIFE OF FLOWERS Bazmark Films Baz Luhrmann (Short) Catherine Knapman/Baz Luhrmann SEE YOU SOON eMotion Entertainment David Mahmoudieh David Stern BROTHERHOOD Unstoppable Entertainment Noel Clarke Jason Maza/Gina Powell ACCESS ALL AREAS Camden Film Co. BrYn Higgins Oliver Veysey/Bill Curbishley AWAY Gateway Films/Slam David Blair Mike Knowles/Louise Delamere NORTHMEN – A VIKING SAGA Elite Film Produktion Claudio Faeh Ralph S. Dietrich/Daniel Hoeltschi INTO THE WOODS (UK Casting Walt Disney Pictures Rob Marshall Consultants) John DeLuca/Marc Platt/ Callum McDougall THE MUPPETS MOST WANTED Walt Disney Pictures James Bobin (UK Casting) Todd Lieberman TOMORROWLAND Walt Disney Pictures Brad Bird (UK Search) Damon Lindelof ANGELICA Pierpoline Films inc Mitchell Lichtenstein Joyce Pierpoline/Richard Lormand IRONCLAD: BATTLE FOR BLOOD Mythic Entertainment Jonathan English Rick Benattar/Andrew Curtis NOT ANOTHER HAPPY ENDING Synchronicity Films John McKaY Claire Mundell BEAUTIFUL CREATURES Alcon Entertainment/Warner Bros. Richard LaGravenese (UK Search) Erwin Stoff / David Valdés STAR TREK 2 (UK Search) Bad Robot/Paramount J.J. Abrams Damon Lindelof KEITH LEMON – THE FILM Generator Entertainment/Lionsgate UK Paul Angunawela Aidan Elliot/Mark Huffam/Simon Bosanquet HIGHWAY TO DHAMPUS Fifty Films Rick McFarland John De Blas Williams ELFIE HOPKINS Size 9/Black & Blue Films Ryan Andrews Michael Wiggs/Jonathan Sothcott Victor Jenkins Casting Ltd T: 020 3457 0506 / M: 07919 -

5115-S.E Hbr Aph 21

HOUSE BILL REPORT ESSB 5115 As Passed House - Amended: April 5, 2021 Title: An act relating to establishing health emergency labor standards. Brief Description: Establishing health emergency labor standards. Sponsors: Senate Committee on Labor, Commerce & Tribal Affairs (originally sponsored by Senators Keiser, Liias, Conway, Kuderer, Lovelett, Nguyen, Salomon, Stanford and Wilson, C.). Brief History: Committee Activity: Labor & Workplace Standards: 3/12/21, 3/24/21 [DPA]. Floor Activity: Passed House: 4/5/21, 68-30. Brief Summary of Engrossed Substitute Bill (As Amended By House) • Creates an occupational disease presumption, for the purposes of workers' compensation, for frontline employees during a public health emergency. • Requires certain employers to notify the Department of Labor and Industries when 10 or more employees have tested positive for the infectious disease during a public health emergency. • Requires employers to provide written notice to employees of potential exposure to the infectious disease during a public health emergency. • Prohibits discrimination against high-risk employees who seek accommodations or use leave options. HOUSE COMMITTEE ON LABOR & WORKPLACE STANDARDS This analysis was prepared by non-partisan legislative staff for the use of legislative members in their deliberations. This analysis is not part of the legislation nor does it constitute a statement of legislative intent. House Bill Report - 1 - ESSB 5115 Majority Report: Do pass as amended. Signed by 6 members: Representatives Sells, Chair; Berry, Vice Chair; Hoff, Ranking Minority Member; Bronoske, Harris and Ortiz- Self. Minority Report: Without recommendation. Signed by 1 member: Representative Mosbrucker, Assistant Ranking Minority Member. Staff: Trudes Tango (786-7384). Background: Workers' Compensation. Workers who are injured in the course of employment or who are affected by an occupational disease are entitled to workers' compensation benefits, which may include medical, temporary time-loss, and other benefits. -

Julius Caesar

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Alan H. Fishman, and The Ohio State University present Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Julius Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Caesar Executive Producer Royal Shakespeare Company By William Shakespeare BAM Harvey Theater Apr 10—13, 16—20 & 23—27 at 7:30pm Apr 13, 20 & 27 at 2pm; Apr 14, 21 & 28 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission Directed by Gregory Doran Designed by Michael Vale Lighting designed by Vince Herbert Music by Akintayo Akinbode Sound designed by Jonathan Ruddick BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Movement by Diane Alison-Mitchell Fights by Kev McCurdy Associate director Gbolahan Obisesan BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Julius Caesar was made possible by a generous gift from Frederick Iseman The first performance of this production took place on May 28, 2012 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Leadership support provided by The Peter Jay Stratford-upon-Avon. Sharp Foundation, Betsy & Ed Cohen / Arete Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation The Royal Shakespeare Company in America is Major support for theater at BAM: presented in collaboration with The Ohio State University. The Corinthian Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Post-Show Talk: Members of the Royal Shakespeare Company The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Friday, April 26. Free to same day ticket holders The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

Senate File 458 - Introduced

Senate File 458 - Introduced SENATE FILE 458 BY COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT (SUCCESSOR TO SF 369) A BILL FOR 1 An Act relating to the established season for hunting game 2 birds on a preserve, and making penalties applicable. 3 BE IT ENACTED BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF IOWA: TLSB 2524SV (1) 89 js/rn S.F. 458 1 Section 1. Section 484B.1, subsection 5, Code 2021, is 2 amended to read as follows: 3 5. “Game birds” means pen-reared birds of the family 4 gallinae order galliformes and pen-reared mallard ducks. 5 Sec. 2. Section 484B.10, subsection 1, Code 2021, is amended 6 to read as follows: 7 1. a. A person shall not take a game bird or ungulate upon 8 a hunting preserve, by shooting in any manner, except during 9 the established season or as authorized by section 481A.56. 10 The established season shall be September 1 through March 31 11 of the succeeding year, both dates inclusive. The owner of 12 a hunting preserve shall establish the hunting season for 13 nonnative, pen-reared ungulates on the hunting preserve. 14 b. A game bird hunting preserve operator may apply for a 15 variance to extend the season date beyond March 31 for that 16 preserve if the monthly precipitation is above average for 17 the county in which the preserve is located for at least two 18 months out of the months of January, February, and March of 19 that season. The state climatologist established pursuant to 20 section 159.5 shall provide official national weather service 21 and community collaborative rain, hail and snow network data 22 to the department to determine whether a variance to the 23 established season shall be granted. -

Lakamie Basin, Wyoming

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR BULLETIN 364 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE LAKAMIE BASIN, WYOMING A PRELIMINARY REPORT BY N. H. DARTON AND C. E. SIEBENTHAL WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1909 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction............................................................. 7 Geography ............................................................... 8 Configuration........................................................ 8 Drainage ............................................................ 9 Climate ............................................................. 9 Temperature...................................................... 9 Precipitation..................................................... 10 Geology ................................................................. 11 Stratigraphy.......................................................... 11 General relations........................../....................... .11 Carboniferous system............................................. 13 Casper formation......................... .................... 13. General character........................................ 13 Thickness ............................................... 13 Local features............................................ 14 Erosion and weathering of limestone slopes ................ 18 Paleontology and age..................................... 19 Correlation .............................................. 20 Forelle limestone............................................ -

Review of the Birth of the Bill of Rights by Robert Allen Rutland

19561 BOOK REVIEWS The Birth of the Bill of Rights. By Robert Allen Rutland. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955. Pp. 243. $5.00. The federal Bill of Rights is one of the most cherished documents in our national hagiography. Its clauses have been invoked by contending parties in every crisis of our history. Every sort of minority interest has sought se- curity in its generous phrases. Its meaning has long been the subject of in- tense controversy among lawyers and judges. The judicial gloss upon its words and phrases has attained enormous proportions. Yet in spite of all this, surprisingly little scholarly work has been done on the history of the Bill of Rights.1 The interest of American historians in constitutional history, once so pronounced, seems to have spent itself. Such newer pastures as those of in- tellectual and business history appear to be greener. It is a long time since our historians have produced a significant new work in the field of constitu- tional history. Political scientists and legal scholars are gradually moving in to fill the vacuum.2 We have had, of course, a number of historical studies of particular aspects of civil liberties,3 but we have never had a thorough, criti- cal, substantial, scholarly study of the origins of the American Bill of Rights. In fact, Rutland's treatise, The Birth of the Bill of Rights, is, to my knowl- edge, the first book-length study by a historical scholar ever written on the subject. While Rutland should be given credit for making the attempt, his book does not by any means fill this gap in historical scholarship. -

Fort Laramie Park History, 1834 – 1977

Fort Laramie NHS: Park History Fort Laramie Park History, 1834-1977 FORT LARAMIE PARK HISTORY 1834-1977 by Merrill J. Mattes September 1980 Rocky Mountain Regional Office National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior TABLE OF CONTENTS fola/history/index.htm Last Updated: 01-Mar-2003 file:///C|/Web/FOLA/history/index.htm [9/7/2007 12:41:47 PM] Fort Laramie NHS: Park History Fort Laramie Park History, 1834-1977 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Author's Preface Part I. FORT LARAMIE, 1834 - 1890 I Introduction II Fur Trappers Discover the Oregon Trail III Fort William, the First Fort Laramie IV Fort John, the Second Fort Laramie V Early Migrations to Oregon and Utah VI Fort Laramie, the U.S. Army, and the Forty-Niners VII The Great California Gold Rush VIII The Indian Problem: Treaty and Massacre IX Overland Transportation and Communications X Uprising of the Sioux and Cheyenne XI Red Cloud's War XII Black Hills Gold and the Sioux Campaigns XIII The Cheyenne-Deadwood Stage Road XIV Decline and Abandonment XV Evolution of the Military Post XVI Fort Laramie as Country Village and Historic Ruin Part II. THE CRUSADE TO SAVE FORT LARAMIE I The Crusade to Save Fort Laramie Footnotes to Part II file:///C|/Web/FOLA/history/contents.htm (1 of 2) [9/7/2007 12:41:48 PM] Fort Laramie NHS: Park History Part III. THE RESTORATION OF FORT LARAMIE 1. Interim State Custodianship 1937-1938 - Greenburg, Rymill and Randels 2. Early Federal Custodianship 1938-1939 - Mattes, Canfield, Humberger and Fraser 3. -

Laramie's West Side Neighborhood Inventory of Historic Buildings

LARAMIE’S WE S T SIDE NEIGHBORHOOD INVENTORY OF HI S T O R I C BUILDINGS Wyoming SHPO: CLG Grant # 56-10-00000.05 Albany County Historic Preservation Board Prepared by the University of Wyoming American Studies Program Mary Humstone, Principal Investigator Carly-Ann Anderson, Graduate Assistant Molly Goldsmith, Graduate Assistant Revised September 2011 LARAMIE’S WEST SIDE NEIGHBORHOOD INVENTORY OF HI S T O R I C BUILDINGS CLG Grant # 56-10-00000.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……………………………………………………………………….2 Description……….………………………………………………………………..3 History……….…………………………………………………………………… 6 Methodology……….…………………………………………………………… 15 Survey Explanation………………………………………………………………18 Recommendation for a National Register of Historic Places District ………..…20 List of Buildings Surveyed (table)……………………………………………….22 Map Showing Boundaries of the Survey Area…………………………………..32 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………..33 Wyoming Architectural Inventory Forms (248) for Laramie’s West Side Neighborhood (attached as separate electronic document on CD) Cover photo: Store and filling station, 312 S. Cedar Street, undated (courtesy of the American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming) Laramie’s West Side Neighborhood Inventory of Historic Buildings Page 1 INTRODUCTION In July, 2010, the University of Wyoming American Studies Program (UW-AMST) entered into an agreement with the Albany County Historic Preservation Board to complete an inventory of historic buildings in a 32-block residential area of Laramie. The project was undertaken by UW-AMST as part of the public-sector component of the American Studies curriculum. Laramie’s West Side neighborhood comprises all of the residential blocks west of the Union Pacific Railroad tracks and east of the Laramie River. However, the blocks north of Clark Street were surveyed in a separate project (“Clark Street North”).1 Therefore, this survey project encompassed only the blocks from Clark Street south to Park Avenue.