Using History to Understand the Consensual Forest Management Model in the Terai, Nepal1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Four Ana and One Modem House: a Spatial Ethnography of Kathmandu's Urbanizing Periphery

I Four Ana and One Modem House: A Spatial Ethnography of Kathmandu's Urbanizing Periphery Andrew Stephen Nelson Denton, Texas M.A. University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, December 2004 B.A. Grinnell College, December 2000 A Disse11ation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Virginia May 2013 II Table of Contents Introduction Chapter 1: An Intellectual Journey to the Urban Periphery 1 Part I: The Alienation of Farm Land 23 Chapter 2: From Newar Urbanism to Nepali Suburbanism: 27 A Social History of Kathmandu’s Sprawl Chapter 3: Jyāpu Farmers, Dalāl Land Pimps, and Housing Companies: 58 Land in a Time of Urbanization Part II: The Householder’s Burden 88 Chapter 4: Fixity within Mobility: 91 Relocating to the Urban Periphery and Beyond Chapter 5: American Apartments, Bihar Boxes, and a Neo-Newari 122 Renaissance: the Dual Logic of New Kathmandu Houses Part III: The Anxiety of Living amongst Strangers 167 Chapter 6: Becoming a ‘Social’ Neighbor: 171 Ethnicity and the Construction of the Moral Community Chapter 7: Searching for the State in the Urban Periphery: 202 The Local Politics of Public and Private Infrastructure Epilogue 229 Appendices 237 Bibliography 242 III Abstract This dissertation concerns the relationship between the rapid transformation of Kathmandu Valley’s urban periphery and the social relations of post-insurgency Nepal. Starting in the 1970s, and rapidly increasing since the 2000s, land outside of the Valley’s Newar cities has transformed from agricultural fields into a mixed development of planned and unplanned localities consisting of migrants from the hinterland and urbanites from the city center. -

Chronology of Major Political Events in Contemporary Nepal

Chronology of major political events in contemporary Nepal 1846–1951 1962 Nepal is ruled by hereditary prime ministers from the Rana clan Mahendra introduces the Partyless Panchayat System under with Shah kings as figureheads. Prime Minister Padma Shamsher a new constitution which places the monarch at the apex of power. promulgates the country’s first constitution, the Government of Nepal The CPN separates into pro-Moscow and pro-Beijing factions, Act, in 1948 but it is never implemented. beginning the pattern of splits and mergers that has continued to the present. 1951 1963 An armed movement led by the Nepali Congress (NC) party, founded in India, ends Rana rule and restores the primacy of the Shah The 1854 Muluki Ain (Law of the Land) is replaced by the new monarchy. King Tribhuvan announces the election to a constituent Muluki Ain. The old Muluki Ain had stratified the society into a rigid assembly and introduces the Interim Government of Nepal Act 1951. caste hierarchy and regulated all social interactions. The most notable feature was in punishment – the lower one’s position in the hierarchy 1951–59 the higher the punishment for the same crime. Governments form and fall as political parties tussle among 1972 themselves and with an increasingly assertive palace. Tribhuvan’s son, Mahendra, ascends to the throne in 1955 and begins Following Mahendra’s death, Birendra becomes king. consolidating power. 1974 1959 A faction of the CPN announces the formation The first parliamentary election is held under the new Constitution of CPN–Fourth Congress. of the Kingdom of Nepal, drafted by the palace. -

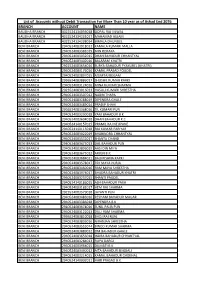

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

(A) S. Trrrs{ (B) St Ig{Qi 1A)Ffi

SET-A I Administrative tribunals in India are not I qnt d wrsatq qqftrq {Eii q1 rqrq-cr r'at established by : q1qrfi t' : (A) President (B) Supreme Court (A) n6qqfr ERr (B) sdqqrqEqERr (C) Chief Minister (D) All ofthese (C) E@c* ERr (D) sri-fi sqt ERr 2. Chairman of l4th Finance Commission is : 2. ffi fq-d en+rr * erqs{ * : (A) C. Rangrajan (B) Raehurajan (A) S. trRrs{ (B) st Ig{qi (C) Y. V. Reddy (D) V.K. Menon (c) sri.d tq$ (D) d. d'. trr 3. The Consumer Protection Act,, 1986 came ., sq+ftI qtqTUI sfqt{qq 1986, sil tTrrl into force on : Eiff ? (A) 1e87 (B) r9e0 (A) 1e87 (B) 19e0 (C) 1991 @) Noneof these (c) leel (D) fl+ t 6ti Tfi 4. Arsenic poisoning from drinking water leads 4 ++ + q+ q s16f65-t*v* +'nq wr *m to: B: (A) Cold @) Keratosis (A) ssT (B) +{dFss (C) Ttphoid @) None of these (q zIqsl{s (D) 3T+{a{+$:rd 5. The aim of "Skill India Mission" is to equip 5. "fisa EFsqr fts1q" q1 g-<{q f"-s s{ 500 million Indians with skills by which year- a-*'soo fqfu{H Sqlet qi g{(r< q{r+ t z (A) 2030 (B) 202s (A) 2030 (B) 202s (c) 2022 @) 2020 (c) 2022 (D) 2020 6, In which state the first Non-Government 6. r+q {q c qr{dlq Td 6,,r T6-dr rR-qrsrt Railway Project oflndian Railways has been i-d cRqhi-{ Erd d i W E1 .rfr- commissioned recently ? 1a)ffi (B) f{ffiq (A) Delhi (B) Sikkim (c) q6Rrq (D) re{rd (C) Maharashtra (D) Gujarat 7. -

A Study of the Treaty of the First Tibet-Gorkha War of 1789

CHAPTER 7 A Study of the Treaty of the First Tibet-Gorkha War of 1789 Yuri Komatsubara Introduction In 1788, the Gorkha kingdom of Nepal attacked the gTsang district of Tibet and the first Tibet-Gorkha war broke out. Although Tibet concluded a treaty with the Gorkha to end the war in 1789, it failed to pay the reparations to the Gorkhas stipulated in the treaty. Therefore, the Gorkha armies invaded Tibet again in 1791 and the second Tibet-Gorkha war commenced. On that occa- sion, the Qing court sent a large number of troops to attack the Gorkha armies and the war was over the next year. After these wars, the Qing established Article 29 of the imperial regulations for Tibet (欽定蔵内善後章程二十九条) in 1793. It is said that the Qing court became more influential in Tibetan poli- tics after these wars. That is, the first Tibet-Gorkha war provided an oppor- tunity for the Qing to change its political policies regarding Tibet. From the view point of the South Asian relationship, the Tibet-Gorkha war was the first confrontation between Tibet, Nepal and the Qing. In this way, the war was an important event between Tibet, Nepal and China. Nevertheless, the whole text of the treaty of the first Tibet-Gorkha war was unknown for a long time. Sato (1986: 584) noted that, at that time, the entire contents of the treaty of 1789 were completely unknown. Rose (1971: 42) pointed out that this treaty actually consisted of a number of a letters exchanged between the signatories, and that no single, authoritative text existed. -

Bennike (2013)

Governing the Hills Imperial Landscapes, National Territories and Production of Place between Naya Nepal and Incredible India! Bennike, Rune Bolding Publication date: 2013 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Bennike, R. B. (2013). Governing the Hills: Imperial Landscapes, National Territories and Production of Place between Naya Nepal and Incredible India! Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen . Download date: 03. okt.. 2021 Ph.D. dissertation 2013/4 RUNE BOLDING BENNIKE ISBN: 87-7393-696-0 ISSN: 1600-7557 RUNE BOLDING BENNIKE Governing the Hills Imperial Landscapes, National Territories and Production of Place between Naya Nepal and Incredible India! Incredible India! has ostensibly stepped out of the “imaginary waiting room of G overning the Hills RUNE BOLDING BENNIKE history” and joined the ranks of modern, developed and branded nations. And Naya Nepal is moving towards a “federal, democratic, and republican” future. Concomitantly, a range of claims to local autonomy brings together local move- ments and global processes in novel ways. In fact, local place-making itself has been globalised. This dissertation asks what happens when the increasingly globalised production of places collides with a resilient national order of things in the Himalayan hills. It investigates movements for the establishment of a Limbuwan and Gorkhaland state on either side of the border between eastern Nepal and north-eastern India. Through the engagement with this area, the dissertation argues that we need to rethink the spatiality of government in order to understand the contemporary conditions for government as well as local autonomy. Across imperial landscapes, national territories and global place-making, the dis- sertation documents novel collisions between refashioned imperial differences and resilient national monopolies on political authority. -

Tourism in Gorkha: a Proposition to Revive Tourism After Devastating Earthquakes

Tourism in Gorkha: A proposition to Revive Tourism After Devastating Earthquakes Him Lal Ghimire* Abstract Gorkha, the epicenter of devastating earthquake 2015 is one of the important tourist destinations of Nepal. Tourism is vulnerable sector that has been experiencing major crises from disasters. Nepal is one of the world’s 20 most disaster-prone countries where earthquakes are unique challenges for tourism. Nepal has to be very optimistic about the future of tourism as it has huge potentials to be the top class tourist destinations by implementing best practices and services. Gorkha tourism requires a strategy that will help manage crises and rapid recovery from the damages and losses. This paper attempts to explain tourism potentials of Gorkha, analyze the impacts of devastating earthquakes on tourism and outline guidelines to revive tourism in Gorkha. Key words: Disasters. challenges, strategies, planning, mitigation, positive return. Background Gorkha is one of the important tourist destinations in Nepal. Despite its natural beauty, historical and religious importance, diverse culture, very close from the capital city Kathmandu and other important touristic destinations Pokhara and Chitwan, tourism in Gorkha could not have been developed expressively. Gorkha was the epicenter of 7.8 earthquake on April 25, 2015 in Nepal that damaged or destroyed the tourism products and tourism activities were largely affected. Tourism is an expanding worldwide phenomenon, and has been observed that by the next century, tourism will be the single largest industry in the world. Today, tourism is also the subject of great media attention (Ghimire, 2014:98). Tourism industry, arguably one of the most important sources of income and foreign exchange, is growing rapidly. -

Chemjong Cornellgrad 0058F

“LIMBUWAN IS OUR HOME-LAND, NEPAL IS OUR COUNTRY”: HISTORY, TERRITORY, AND IDENTITY IN LIMBUWAN’S MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Dambar Dhoj Chemjong December 2017 © 2017 Dambar Dhoj Chemjong “LIMBUWAN IS OUR HOME, NEPAL IS OUR COUNTRY”: HISTORY, TERRITORY, AND IDENTITY IN LIMBUWAN’S MOVEMENT Dambar Dhoj Chemjong, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 This dissertation investigates identity politics in Nepal and collective identities by studying the ancestral history, territory, and place-naming of Limbus in east Nepal. This dissertation juxtaposes political movements waged by Limbu indigenous people with the Nepali state makers, especially aryan Hindu ruling caste groups. This study examines the indigenous people’s history, particularly the history of war against conquerors, as a resource for political movements today, thereby illustrating the link between ancestral pasts and present day political relationships. Ethnographically, this dissertation highlights the resurrection of ancestral war heroes and invokes war scenes from the past as sources of inspiration for people living today, thereby demonstrating that people make their own history under given circumstances. On the basis of ethnographic examples that speak about the Limbus’ imagination and political movements vis-à-vis the Limbuwan’s history, it is argued in this dissertation that there can not be a singular history of Nepal. Rather there are multiple histories in Nepal, given that the people themselves are producers of their own history. Based on ethnographic data, this dissertation also aims to debunk the received understanding across Nepal that the history of Nepal was built by Kings. -

A Himalayan Case Study

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 35 Number 2 Article 11 January 2016 Reconsidering State-Society Relations in South Asia: A Himalayan Case Study Sanjog Rupakheti Loyola University New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Rupakheti, Sanjog. 2016. Reconsidering State-Society Relations in South Asia: A Himalayan Case Study. HIMALAYA 35(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol35/iss2/11 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reconsidering State-Society Relations in South Asia: A Himalayan Case Study Acknowledgements I acknowledge with gratitude the support and guidance of Sumit Guha and Indrani Chatterjee on the larger research project, from which this article is drawn. For their careful and insightful suggestions on the earlier drafts, I thank Ashley Howard, Paul Buehler, and the two anonymous reviewers of Himalaya. I am especially grateful to Catherine Warner and Arik Moran (editors of this special issue), for their meticulous work on the earlier drafts. Any -

Relationship Between Education and Poverty in Nepal

Economic Journal of Development Issues Vol. 15 & 16 No. 1-2 (2013) Combined Issue Relationship Between Education ... RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EDUCATION AND POVERTY IN NEPAL Surya Bahadur Thapa* Abstract Education is an important component of human resource development. It is the first most important determinant of income poverty. This paper aims to explore political economy of the country simply dealing with secondary data to produce the general statement relevant to the policy makers/ leaders of the country. In this context this paper tries to establish the linkage between income poverty and different levels of education. For this purpose secondary data published by United Nations Development Program and Central Bureau of Statistics were used. The descriptive findings based on these data provide fresh insights into some of the widely recognized perceptions on the extent and causes of educational deprivation of the poor that the level of educational attainment is a positive function of the levels of income. Key Words: Education Poverty, Income Poverty, Literacy rate, Mean Years of Schooling, Gross Enrollment Rate 1. INTRODUCTION Poverty has been defined as income poverty in conventional sense. Rowntree (1901) used this concept, at first, in his classic study of poverty of the English city of York. However, income poverty is widely used today being its own limitations. To overcome these limitations the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has developed two alternative indices: Human Development Index (HDI) and Human Poverty Index (HPI). The UNDP has argued that poverty can evolve not only due to lack of the necessities of material well- being but also due to the denial of opportunities for living a tolerable life. -

Aryan and Non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the Linguistic Situation, C

Michael Witzel, Harvard University Aryan and non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the linguistic situation, c. 1900-500 B.C.. § 1. Introduction To describe and interpret the linguistic situation in Northern India1 in the second and the early first millennium B.C. is a difficult undertaking. We cannot yet read and interpret the Indus script with any degree of certainty, and we do not even know the language(s) underlying these inscriptions. Consequently, we can use only data from * archaeology, which provides, by now, a host of data; however, they are often ambiguous as to the social and, by their very nature, as to the linguistic nature of their bearers; * testimony of the Vedic texts , which are restricted, for the most part, to just one of the several groups of people that inhabited Northern India. But it is precisely the linguistic facts which often provide the only independent measure to localize and date the texts; * the testimony of the languages that have been spoken in South Asia for the past four thousand years and have left traces in the older texts. Apart from Vedic Skt., such sources are scarce for the older periods, i.e. the 2 millennia B.C. However, scholarly attention is too much focused on the early Vedic texts and on archaeology. Early Buddhist sources from the end of the first millennium B.C., as well as early Jaina sources and the Epics (with still undetermined dates of their various strata) must be compared as well, though with caution. The amount of attention paid to Vedic Skt. -

ETHNIC, SOCIAL, OCCUPATIONAL and CULTURAL BACKGROUND of the WOMEN TEA PLANTATION WORKERS Chapter-4

Chapjer- 4 · ETHNIC, SOCIAL, OCCUPATIONAL AND CULTURAL BACKGROUND OF THE WOMEN TEA PLANTATION WORKERS Chapter-4 ETHNIC, SOCIAL, OCCUPATIONAL AND CULTURAL BACKGROUND OF THE WOMEN TEA PLANTATION WORKERS. 4.1 Migration History : Migration is a special process, associated with the redistribution of population. Movement of an individual or groups which involves a permanent or Semi-permanent change of usual residence is migration (Wilson: 1985) The more authentic history ofNepalis migration to Darjeeling hills begins in the middle of the nineteenth century only when the East India company's trade interest had been focused on this region. The first large scale cultivation of tea for commercial purpose took place in 1852 and we have already discussed in the previous chapters about the close' interrelations between the growth of tea gardens and rapid increase of the population of Darjeeling mainly due to the migration of Nepalis from the hills of Nepal. The growth of tea gardens as a major factor in the migration of the Nepalis to this region has been duly emphasized by various scholars like L.S.S.O' Mally (1907) and later by Sunil Munsi (1980). Besides tea industry, the recruitment of Nepalis to British army is another important factor for the migration (Kansakar: 1980). As the old historical records shows the establishment of cantonments and barracks and a battalion of British infantry and Artillery stationed at Lebong (in 1847), Katapahar and Jalapahar in 1848. The Anglo-Nepalis Peace Treaty 1816 better known as the Segauli Treaty empowered the British Govt. to raise three regiments of Nepalis hill people in the British army.