Communities on the Boundary of the Mkuze Protected Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vegetation Ecology of the Lower Mkuze River Floodplain, Northern

The vegetation ecology ofthe lower Mkuze River floodplain, northern KwaZulu-Natal: A landscape ecology perspective. Submitted in fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree ofMaster ofScience in the School ofLife and Environmental Sciences, University ofNatal-Durban. 2001 Marian J. Neal PREFACE The work described was carried out between January 1999 and December 2001, in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences (previously the Department of Geographical and Environmental Sciences) at the University of Natal-Durban, under the supervision of Prof. W.N. Ellery. The study represents original work by the author and has not been submitted in any other form to another university. Where use was made of the work of others, it has been duly acknowledged in the text. 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study fonns part of an ongoing research programme conducted in the Greater Mkuze Wetland System, northern KwaZulu-Natal and was made possible through the funding from Wildlife & Environment Society of southern Africa, the University ofNatal Masters special fund and the National Research Foundation. I would like to acknowledge the following people without whom this thesis would not have been possible: • Prof. Fred Ellery, for the enthusiasm he has for wetlands, for the discussions, time and encouragement and for instilling in me a work ethic I will carry with me throughout my career. • Dr Annika Dahlberg, for advice, support and assistance, especially in the field. • Prof. Gerry Garland, for the assistance and advice during the soil analysis phase. • Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife, for granting pennission to access the study area and for the use of the Manzibomvu camp. Special mention must go to Drikus Gissing for his hospitality and logistical support. -

Biodiversity Sector Plan for the Zululand District Municipality, Kwazulu-Natal

EZEMVELO KZN WILDLIFE Biodiversity Sector Plan for the Zululand District Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal Technical Report February 2010 The Project Team Thorn-Ex cc (Environmental Services) PO Box 800, Hilton, 3245 Pietermaritzbur South Africa Tel: (033) 3431814 Fax: (033) 3431819 Mobile: 084 5014665 [email protected] Marita Thornhill (Project Management & Coordination) AFZELIA Environmental Consultants cc KwaZulu-Natal Western Cape PO Box 95 PO Box 3397 Hilton 3245 Cape Town 8000 Tel: 033 3432931/32 Tel: 072 3900686 Fax: 033 3432033 or Fax: 086 5132112 086 5170900 Mobile: 084 6756052 [email protected] [email protected] Wolfgang Kanz (Biodiversity Specialist Coordinator) John Richardson (GIS) Monde Nembula (Social Facilitation) Tim O’Connor & Associates P.O.Box 379 Hilton 3245 South Africa Tel/ Fax: 27-(0)33-3433491 [email protected] Tim O’Connor (Biodiversity Expert Advice) Zululand Biodiversity Sector Plan (February 2010) 1 Executive Summary The Biodiversity Act introduced several legislated planning tools to assist with the management and conservation of South Africa’s biological diversity. These include the declaration of “Bioregions” and the publication of “Bioregional Plans”. Bioregional plans are usually an output of a systematic spatial conservation assessment of a region. They identify areas of conservation priority, and constraints and opportunities for implementation of the plan. The precursor to a Bioregional Plan is a Biodiversity Sector Plan (BSP), which is the official reference for biodiversity priorities to be taken into account in land-use planning and decision-making by all sectors within the District Municipality. The overall aim is to avoid the loss of natural habitat in Critical Biodiversity Areas (CBAs) and prevent the degradation of Ecological Support Areas (ESAs), while encouraging sustainable development in Other Natural Areas. -

KZN Zusub 02022018 Uphong

!C !C^ ñ!.!C !C $ !C^ ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^!C ^ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^$ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ !C ñ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^!C ^ !C !C !C ñ ^ !C !C ^ $ ^$!C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !.^ ñ $ !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C $ !C !C !C ñ $ !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ñ!C!. ^ ^ ^ !C $!. !C^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C ^ !.!C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ñ !C !C !C ñ !.^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !Cñ ^$ ^ !C ñ !C ñ!C!.^ !C !. !C !C ^ ^ ñ !. !C !C $^ ^ñ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !. ñ!C !C !C ^ !C ñ!.^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C ^!. !. !. !C ^ !C !C !. !C ^ !C !C ^ !C ñ!C !C !. !C $^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !. -

Proposed Senekal 1 Solar Energy Facility Near Mkuze, Kwazulu-Natal

PROPOSED SENEKAL 1 SOLAR ENERGY FACILITY NEAR MKUZE, KWAZULU-NATAL DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME Submitted as part of the draft Basic Assessment Report August 2014 Prepared for: Building Energy SpA 72 Waterkant Street Cape Town 8001 South Africa Prepared by Savannah Environmental Pty Ltd First Floor unit, Block 2 5 Woodlands Drive Office Park, Corner Woodlands Drive & Western Service Road, WOODMEAD, Gauteng po box 148, sunninghill, 2157 Tel: +27 (0)11 656 3237 Fax: +27 (0)86 684 0547 E-mail: [email protected] www.savannahsa.com Proposed Senekal 1 Solar Energy Facility Near Mkuze, KwaZulu-Natal Draft Environmental Management Programme August 2014 PROJECT DETAILS DEA Reference No. : 14/12/16/3/3/2/1226 Title : Environmental Basic Assessment Process Proposed Senekal 1 Solar Energy Facility Near Mkuze, KwaZulu-Natal Authors : Savannah Environmental Sheila Muniongo Karen Jodas Sub-consultants : Scherman Colloty & Associates (Ecologist) Heritage Contracts and Archaeological Consulting (Heritage) Johann Lanz Soil Scientist (Soil) Barry Millsteed (Palaeontologist) Client : Building Energy SpA When used as a reference this report should be cited as: Savannah Environmental (2014) Basic Assessment Process - Draft Environmental Management Programme: Proposed Senekal 1 Solar Energy Facility Near Mkuze, KwaZulu-Natal COPYRIGHT RESERVED This technical report has been produced for Building Energy SpA. The intellectual property contained in this report remains vested in Savannah Environmental and Building Energy SpA. No part of the report may be reproduced in any manner without written permission from Building Energy SpA or Savannah Environmental (Pty) Ltd. Project Details Page ii Proposed Senekal 1 Solar Energy Facility Near Mkuze, KwaZulu-Natal Draft Environmental Management Programme August 2014 DEFINITIONS AND TERMINOLOGY Alternatives: Alternatives are different means of meeting the general purpose and need of a proposed activity. -

Jozini Local Municipality

JOZINI LOCAL MUNICIPALITY Integrated Development Plan (IDP) Review for 2011/12 FY Mission: “Jozini Municipality intends to be the best municipality in service delivery.” Circle Street, Bottom Town, Jozini 3969 Tel: 035 572 1292 Fax: 053 572 1266 Website:www.jozini.org.za CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 : EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 5 1.2. GEOLOGY AND SOILS 6 CHAPTER 2 : THE REVIEW PROCESS 2.1. CONTEXT OF THE 2011/12 IDP REVIEW 12 2.2. LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 13 2.2.1. National Planning context 13 2.2.2. Provincial Planning context 15 2.2.3. Local Planning context 17 2.3. THE NEED FOR AN IDP REVIEW PROCESS 19 2.3.1. Comments from the MEC ON 2010/11 IDP 20 2.3.1. Local Government Turnaround Strategy 23 Objectives of the Turnaround Strategy 2.4. STRATEGIC FOCUS AREAS 23 2.4.1. National Outcome Delivery Agreements 24 2.4.2. Institutional Arrangements 27 2.4.3. Inter-governmental Relations 30 CHAPTER 3: ANALYSIS PHASE 3.1. ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE AND INSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS 31 3.1.1. Powers and functions of Jozini municipality 31 3.1.2. Political structure 31 3.1.3. Management structure 35 3.1.4. Traditional Councils and their role 41 3.2. STATUS QUO ANALYSIS 42 3.2.1. Demographics 42 3.2.1.1. Age distribution 43 3.2.1.2. Dependancy ratio 44 3.2.1.3. Household income 46 3.2.1.4. Levels of education 47 3.3. SERVICE DELIVERY AND INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT 48 3.3.1. Water 48 3.3.2. -

Export This Category As A

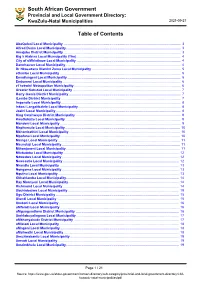

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory: KwaZulu-Natal Municipalities 2021-09-27 Table of Contents AbaQulusi Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Alfred Duma Local Municipality ........................................................................................................................... 3 Amajuba District Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Big 5 Hlabisa Local Municipality (The) ................................................................................................................ 4 City of uMhlathuze Local Municipality ................................................................................................................ 4 Dannhauser Local Municipality ............................................................................................................................ 4 Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma Local Municipality ................................................................................................ 5 eDumbe Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 5 Emadlangeni Local Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 6 Endumeni Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. -

Zululand • Kwazulu-Natal

ZULULAND • KWAZULU-NATAL www.bayetezulu.co.za SEPTEMBER 2019 AFRICA Superb Location Bayete Zulu Lodges are set in the heart of the ‘Big-5’ Manyoni Private Game Reserve, considered to be one of the most densely stocked and ecologically balanced in northern KwaZulu-Natal. The Manyoni Private Game Reserve covering Kruger National 23 000 hectares consists of a varied landscape BOTSWANA Park of mountains, open plains and dense riverine woodlands. Here the ‘Big-5’, along with a MPUMALANGA wide variety of other wildlife roam freely, and Johannesburg MOZAMBIQUE exceptional safaris can be experienced. GAUTENG SWAZILAND NAMIBIA An easy three-hour drive from King Shaka BAYETE ZULU LODGES Airport in Durban, just 33km north of Hulhluwe, Hluhluwe FREE STATE and a six hour drive from Johannesburg. KWAZULU -NATAL LESOTHO Bayete Zulu Lodges offer a range of catered and NORTHERN CAPE Durban self catering accommodation. Sensational game viewing in open 4x4 vehicles with knowledge- able guides, coupled with warm hospitality and breathtaking views makes Bayete Zulu the EASTERN CAPE perfect place to relax and soak up the sights and INDIAN sounds of the African bush. WESTERN CAPE OCEAN THE RESERVE DIRECTIONS LOCATION I THE RESERVE I WEDDINGS I BAYETE HOMESTEAD I LITTLE BAYETE I GAME DRIVES I ELEPHANT INTERACTIONS I DIRECTIONS I DETAILS ‘BIG-5’ Manyoni Game Reserve Manyoni Private Game Reserve lies in the heart of Zululand, an area that is world renowned for its spectacular game viewing, rich cultural traditions, and conservation history. Initially formed as part of the WWF black rhino range expansion project, Manyoni has become one of the premier ‘Big-5’ safari destinations in KwaZulu-Natal with a strong focus on endangered species conservation. -

Ultimate South Africa

Gorgeous Bushshrike – Mkuze Game Reserve | © Martin Benadie (Note: All images used to illustrate this tour report were taken on the actual 2017 tour). ULTIMATE SOUTH AFRICA 10 NOVEMBER – 4 DECEMBER 2017 LEADER: MARTIN BENADIE The 2017 Birdquest Ultimate South Africa tour certainly lived up to its name – yet again! An outstanding birding destination and this tour delivered, with an amazingly high proportion of the targets (the hoped for endemics, regional endemics and specialities) being not only found, but also seen remarkably well. 510 bird species were seen well by all group members (out of 523 species recorded on tour). The mammals also put in a good showing with over 50 species observed. Top birds included the fantastic Pink-throated Twinspot, confiding Victorin’s and Barratt’s Warblers, magical Blue Swallows, the stunning Drakensberg Rockjumper, which along with its close relative the Cape Rockjumper, and the two sugarbirds (Cape and Gurney’s Sugarbirds), are all truly iconic species. Other memorable specials included the graceful Black Harrier, Green Barbet, the trio of wonderful cranes, Bokmakierie, Cinnamon-breasted Warbler, Karoo Eremomela and nine superb species of bustard. Colour was added by showy Cape Parrots, vivid Gorgeous Bushshrikes, Ground Woodpecker and three species of splendid turacos, elegance by the Buff-streaked Chats, comedy by African Penguins and rarity by Rudd’s Lark and Taita Falcon, not to mention the rapidly disappearing vultures! Four per cent of our species were members of the Alaudidae family as we saw 22 species of lark in what has to be the lark capital of the world. The great thing was that we saw them all well enough for all to appreciate their subtle differences. -

Mkuze Interchange Heritage Impact Assessment.Pdf

Mkuze Interchange CULTURAL HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION OF MKUZE INTERCHANGE ON NATIONAL ROUTE 2, SECTION 31 (KM29.30), MKUZE, JOZINI LOCAL MUNICIPALITY FOR: ENVIROEDGE Frans Prins MA (Archaeology) Hester Roodt BA (Hons) Archaeology; Hons (Anatomy) P.O. Box 947 Howick 3290 [email protected] 30 December 2014 Fax: 0867636380 www.activeheritage.webs.com Active Heritage for Enviroedge i Mkuze Interchange TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROJECT .............................................................. 1 1.1. Details of the area surveyed: ........................................................................................... 2 2 BACKGROUND TO ARCHAEOLOGICAL HISTORY OF AREA ............................................. 2 3 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE SURVEY ................................................................ 6 3.1 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Restrictions encountered during the survey ..................................................................... 7 3.2.1 Visibility ........................................................................................................................ 7 3.2.2 Disturbance .................................................................................................................. 7 3.3 Details of equipment used in the survey ........................................................................... 7 4 DESCRIPTION OF SITES -

Umhlabuyalingana NU Mfakubeka 16455 Qotho 9714 Tembe Engozini Kwamazambane !C Enkovukeni !C !C ^!

!C ^ !.C! !C ñ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ^!C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ^ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C !.!C^ ñ!C ñ !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C ñ ^!C !. ^ !C !C ñ!C ^ !C !C ^ ^!C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !.^ !C !C ñ !C !C ^ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !. !C !C !C!C !C ñ!C!. ^ ^ ^ !C !. !C^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C!C !. !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !.!C !C !C ñ !C !C^ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C!.^ !C !C !C !C !C ^!Cñ ^ ^ñ!C !C ñ!C!.^ !C !C ^!. ^ !C ñ !. !C ^ ñ^!C ^ !C ^ ^ ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C !. ñ!C !C !C ^ ñ!C.^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^!. !. !. !C ^ !C !C!. !C ^ !C !C^ !C !C !C ñ !. !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !. -

Big 5-Hlabisa Consolidated Idp REVIEW 2016/17

FINAL IDP 2020/21- 2022/2023 5 TH GENERATION Prepared by: Executive Department IDP/PMS Section Supported by: IDP Steering Committee IDP Representative Forum Hlabisa Municipality Lot 808 off Masson Street Hlabisa 3937 035- 838 8500 [email protected] www.big5hlabisa.gov.za MISSION A sustainable economy achieved through service delivery and development facilitation for prosperity and improved quality of life. Vision Statement In light of the Vision We are visionary leaders who serve through community driven initiatives, high performance, sound work ethic, innovation, cutting edge resources and synergistic partnerships. Our Core Values Professionalism Integrity Competency Team work 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. MAYOR’S FOREWORD ............................................................................................... 1 II. MUNICIPAL MANAGER’S OVERVIEW .................................................................. 4 III. POWERS AND FUNCTIONS ................................................................................... 5 IV. STRUCTURE OF THE DOCUMENT ..................................................................... 8 1. SECTION A: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... 9 1.1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 9 1.2. SPATIAL OVERVIEW ............................................................................................. 9 1.3. BRIEF DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE .................................................................... -

Big 5-Hlabisa Consolidated Idp REVIEW 2016/17

= FINAL IDP 2021/2022- 2022/2023 5 TH GENERATION Prepared by: Executive Department IDP/PMS Section Supported by: IDP Steering Committee IDP Representative Forum Hlabisa Municipality Lot 808 off Masson Street Hlabisa 3937 035- 838 8500 [email protected] www.big5hlabisa.gov.za MISSION A sustainable economy achieved through service delivery and development facilitation for prosperity and improved quality of life. Vision Statement In light of th Vision We are visionary leaders who serve through community driven initiatives, high performance, sound work ethic, innovation, cutting edge resources and synergistic partnerships. Our Core Values Professionalism Integrity Competency Team work 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. MAYOR’S FOREWORD ..................................................................................... 1 II. MUNICIPAL MANAGER’S OVERVIEW ............................................................. 4 III. POWERS AND FUNCTIONS ......................................................................... 6 IV. STRUCTURE OF THE DOCUMENT .............................................................. 8 1. SECTION A: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................... 9 1.1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 9 1.2. SPATIAL OVERVIEW .................................................................................... 9 1.3. BRIEF DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE .............................................................. 12 2.2. PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT