Mkuze Interchange Heritage Impact Assessment.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vegetation Ecology of the Lower Mkuze River Floodplain, Northern

The vegetation ecology ofthe lower Mkuze River floodplain, northern KwaZulu-Natal: A landscape ecology perspective. Submitted in fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree ofMaster ofScience in the School ofLife and Environmental Sciences, University ofNatal-Durban. 2001 Marian J. Neal PREFACE The work described was carried out between January 1999 and December 2001, in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences (previously the Department of Geographical and Environmental Sciences) at the University of Natal-Durban, under the supervision of Prof. W.N. Ellery. The study represents original work by the author and has not been submitted in any other form to another university. Where use was made of the work of others, it has been duly acknowledged in the text. 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study fonns part of an ongoing research programme conducted in the Greater Mkuze Wetland System, northern KwaZulu-Natal and was made possible through the funding from Wildlife & Environment Society of southern Africa, the University ofNatal Masters special fund and the National Research Foundation. I would like to acknowledge the following people without whom this thesis would not have been possible: • Prof. Fred Ellery, for the enthusiasm he has for wetlands, for the discussions, time and encouragement and for instilling in me a work ethic I will carry with me throughout my career. • Dr Annika Dahlberg, for advice, support and assistance, especially in the field. • Prof. Gerry Garland, for the assistance and advice during the soil analysis phase. • Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife, for granting pennission to access the study area and for the use of the Manzibomvu camp. Special mention must go to Drikus Gissing for his hospitality and logistical support. -

Swaziland's Proposed Land Deal with South Africa - the Case of Ingwavuma and Kangwane*

Swaziland's Proposed Land Deal with South Africa - The Case of Ingwavuma and Kangwane* By Wolfgang Senftleben Since the Gambia united with Senegal under a Confederation recently, Swaziland (with an area of 17 363 sq.km) has been the smallest country in mainland Africa' (followed by Dj ibouti with 21 783 sq.km), but this could change very soon. In mid-1982 it was announced that the Republic of South Africa is willing to transfer two of its land areas totalling approximately 10 000 sq.km to the Kingdom of Swaziland. Together, these two areas would increase Swaziland's size by more than 60 per cent and give the hitherto land-locked state2 access to the sea with a potential port at Kosi Bay, just below Mozambique. The principal benefits for both countries are only too obvious: For Swaziland it means a realization of a long-standing dream of the late King Sobhuza II to incorporate all lands of the traditionally Swazi realm, besides ending Swaziland's status as a land-locked state. For South Africa it would be a major success of her apartheid policy (or territorial separation) by excommunicating two of its African tribaI areas with a population of together 850 000 people, which would give South Africa a tacit quasi-re cognition of her homeland policy, besides the advantage of creating a buffer zone between white-ruled South Africa and Marxist-orientated Mozambique for security reasons. However, such land transactions are carried out at the expenses of the local population in the respective areas of Ingwavuma and KaNgwane. -

Biodiversity Sector Plan for the Zululand District Municipality, Kwazulu-Natal

EZEMVELO KZN WILDLIFE Biodiversity Sector Plan for the Zululand District Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal Technical Report February 2010 The Project Team Thorn-Ex cc (Environmental Services) PO Box 800, Hilton, 3245 Pietermaritzbur South Africa Tel: (033) 3431814 Fax: (033) 3431819 Mobile: 084 5014665 [email protected] Marita Thornhill (Project Management & Coordination) AFZELIA Environmental Consultants cc KwaZulu-Natal Western Cape PO Box 95 PO Box 3397 Hilton 3245 Cape Town 8000 Tel: 033 3432931/32 Tel: 072 3900686 Fax: 033 3432033 or Fax: 086 5132112 086 5170900 Mobile: 084 6756052 [email protected] [email protected] Wolfgang Kanz (Biodiversity Specialist Coordinator) John Richardson (GIS) Monde Nembula (Social Facilitation) Tim O’Connor & Associates P.O.Box 379 Hilton 3245 South Africa Tel/ Fax: 27-(0)33-3433491 [email protected] Tim O’Connor (Biodiversity Expert Advice) Zululand Biodiversity Sector Plan (February 2010) 1 Executive Summary The Biodiversity Act introduced several legislated planning tools to assist with the management and conservation of South Africa’s biological diversity. These include the declaration of “Bioregions” and the publication of “Bioregional Plans”. Bioregional plans are usually an output of a systematic spatial conservation assessment of a region. They identify areas of conservation priority, and constraints and opportunities for implementation of the plan. The precursor to a Bioregional Plan is a Biodiversity Sector Plan (BSP), which is the official reference for biodiversity priorities to be taken into account in land-use planning and decision-making by all sectors within the District Municipality. The overall aim is to avoid the loss of natural habitat in Critical Biodiversity Areas (CBAs) and prevent the degradation of Ecological Support Areas (ESAs), while encouraging sustainable development in Other Natural Areas. -

KZN Zusub 02022018 Uphong

!C !C^ ñ!.!C !C $ !C^ ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^!C ^ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^$ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ !C ñ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^!C ^ !C !C !C ñ ^ !C !C ^ $ ^$!C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !.^ ñ $ !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C $ !C !C !C ñ $ !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ñ!C!. ^ ^ ^ !C $!. !C^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C ^ !.!C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ñ !C !C !C ñ !.^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !Cñ ^$ ^ !C ñ !C ñ!C!.^ !C !. !C !C ^ ^ ñ !. !C !C $^ ^ñ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !. ñ!C !C !C ^ !C ñ!.^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C ^!. !. !. !C ^ !C !C !. !C ^ !C !C ^ !C ñ!C !C !. !C $^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !. -

Operation Ingwavuma

OPERATION INGWAVUMA Memoirs of a Political commissar UNDER normal circumstances, break with the conventional rule one questions since I was the military participants are expec requiring the writing of military only one in that meeting who ted to write their memoirs only memoirs only when the war is was thoroughly acquainted with when the war is over, to give over. Northern Natal, as I was actually them the advantage of looking bom in Zululand and had already at things more objectively, THE NATAL REGIONAL worked as a political operative in weighing both successes and fai COMMAND MEETS the area of Ingwavuma for a pe lures unemotionally, and talcing TO DISCUSS riod of close to two years under advantage of the total outcome 'OPERATION INGWAVUMA' the political structures of the of the whole war period to ap ANC. praise the contribution of single I was summoned to the first After about four hours, our battles. meeting to discuss the implem meeting was over. The task of I took up my pen to write entation of this plan in the un our Military Command was clear. about our experiences in the derground Operational Head We were expected to begin work planning and implementation of quarters of the Natal Regional ing immediately to prepare con 'Operation Ingwavuma' for the Military Command. Also present ditions for the creation of guer following reasons: at-the meeting was the sub-struc rilla zones in Northern Natal. 1)1 was asked to do so by the ture of this Command, called the The area of Ingwavuma, situated Editor of Dawn, who insisted Northern Natal Military Com on the most Northern tip of that since a special issue of our mand (NNMC) whose specific Natal and also bordering on Swa army's journal was being pre task it was to execute this, task. -

Proposed Senekal 1 Solar Energy Facility Near Mkuze, Kwazulu-Natal

PROPOSED SENEKAL 1 SOLAR ENERGY FACILITY NEAR MKUZE, KWAZULU-NATAL DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME Submitted as part of the draft Basic Assessment Report August 2014 Prepared for: Building Energy SpA 72 Waterkant Street Cape Town 8001 South Africa Prepared by Savannah Environmental Pty Ltd First Floor unit, Block 2 5 Woodlands Drive Office Park, Corner Woodlands Drive & Western Service Road, WOODMEAD, Gauteng po box 148, sunninghill, 2157 Tel: +27 (0)11 656 3237 Fax: +27 (0)86 684 0547 E-mail: [email protected] www.savannahsa.com Proposed Senekal 1 Solar Energy Facility Near Mkuze, KwaZulu-Natal Draft Environmental Management Programme August 2014 PROJECT DETAILS DEA Reference No. : 14/12/16/3/3/2/1226 Title : Environmental Basic Assessment Process Proposed Senekal 1 Solar Energy Facility Near Mkuze, KwaZulu-Natal Authors : Savannah Environmental Sheila Muniongo Karen Jodas Sub-consultants : Scherman Colloty & Associates (Ecologist) Heritage Contracts and Archaeological Consulting (Heritage) Johann Lanz Soil Scientist (Soil) Barry Millsteed (Palaeontologist) Client : Building Energy SpA When used as a reference this report should be cited as: Savannah Environmental (2014) Basic Assessment Process - Draft Environmental Management Programme: Proposed Senekal 1 Solar Energy Facility Near Mkuze, KwaZulu-Natal COPYRIGHT RESERVED This technical report has been produced for Building Energy SpA. The intellectual property contained in this report remains vested in Savannah Environmental and Building Energy SpA. No part of the report may be reproduced in any manner without written permission from Building Energy SpA or Savannah Environmental (Pty) Ltd. Project Details Page ii Proposed Senekal 1 Solar Energy Facility Near Mkuze, KwaZulu-Natal Draft Environmental Management Programme August 2014 DEFINITIONS AND TERMINOLOGY Alternatives: Alternatives are different means of meeting the general purpose and need of a proposed activity. -

Maurice Webb Race Relations Unit

MAURICE WEBB RACE RELATIONS UNIT A DIRECTORY OF RURAL AND PERI-URBAN COMMUNITY BASED ORGANISATIONS IN NATAL T Mzimela CENTRE FOR SOCIAL AND DEVELOPMENT STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NATAL KING GEORGE V AVENUE DURBAN 4001 SOUTH AFRICA * CENTRE FOR SOCIAL AND DEVELOPMENT STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NATAL DURBAN A DIRECTORY OF RURAL AND PERI-URBAN COMMUNITY BASED ORGANISATIONS IN NATAL PRODUCED BY T. MZIMELA MAURICE WEBB RACE RELATIONS UNIT CENTRE FOR SOCIAL AND DEVELOPMENT STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NATAL DURBAN The Centre for Social and Development Studies was established in 1988 through the merger of the Centre for Applied Social Science and the Development Studies Unit. The purpose of the centre is to focus university research in such a way as to make it relevant to the needs of the surrounding developing communities, to generate general awareness of development problems and to assist in aiding the process of appropriate development planning. ISBN No 1-86840-029-8 RURAL AND PERI-URBAN COMMUNITY BASED ORGANIZATIONS This Directory consists of rural COMMUNITY BASED ORGANISATIONS (CBOS) and some organisations from peri-urban areas in Natal. It has been produced by the Maurice Webb Race Relations Unit at the Centre for Social and development Studies which is based at the University of Natal. The directory seeks to facilitate communication amongst community based organisations in pursuance of their goals. The province is divided into five zones : (i) ZONE A: UPPER NOTUERN NATAL REGION: This includes the Mahlabathini, Nquthu, Nhlazatshe, Nongoma and Ulundi districts. (ii) ZONE B: UPPER NORTHERN NATAL COASTAL REGION: This includes Ingwavuma, Kwa-Ngwanase, Hlabisa, Mtubatuba, Empangeni, Eshowe, Mandini, Melmoth, Mthunzini, and Stanger districts. -

ACTIVE HERITAGE Cc

P443, D1886, L1380 Road Upgrade CULTURAL HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED P443, D1886, AND L1380 ROAD UPGRADE NEAR INGWAVUMA, NORTHERN KWAZULU-NATAL ACTIVE HERITAGE cc. Frans Prins MA (Archaeology) P.O. Box 947 Howick 3290 [email protected] 27 October 2013 Fax: 0867636380 www.activeheritage.webs.com Active Heritage for Jeffares and Green i P443, D1886, L1380 Road Upgrade TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROJECT .............................................................. 1 1.1. Details of the area surveyed: ........................................................................................... 2 2 BACKGROUND TO ARCHAEOLOGICAL HISTORY OF AREA ............................................. 2 3 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE SURVEY ................................................................ 7 3.1 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Restrictions encountered during the survey ..................................................................... 7 3.2.1 Visibility ........................................................................................................................ 7 3.2.2 Disturbance .................................................................................................................. 7 3.3 Details of equipment used in the survey ........................................................................... 7 4 DESCRIPTION OF SITES AND MATERIAL OBSERVED ....................................................... -

Jozini Local Municipality

JOZINI LOCAL MUNICIPALITY Integrated Development Plan (IDP) Review for 2011/12 FY Mission: “Jozini Municipality intends to be the best municipality in service delivery.” Circle Street, Bottom Town, Jozini 3969 Tel: 035 572 1292 Fax: 053 572 1266 Website:www.jozini.org.za CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 : EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 5 1.2. GEOLOGY AND SOILS 6 CHAPTER 2 : THE REVIEW PROCESS 2.1. CONTEXT OF THE 2011/12 IDP REVIEW 12 2.2. LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 13 2.2.1. National Planning context 13 2.2.2. Provincial Planning context 15 2.2.3. Local Planning context 17 2.3. THE NEED FOR AN IDP REVIEW PROCESS 19 2.3.1. Comments from the MEC ON 2010/11 IDP 20 2.3.1. Local Government Turnaround Strategy 23 Objectives of the Turnaround Strategy 2.4. STRATEGIC FOCUS AREAS 23 2.4.1. National Outcome Delivery Agreements 24 2.4.2. Institutional Arrangements 27 2.4.3. Inter-governmental Relations 30 CHAPTER 3: ANALYSIS PHASE 3.1. ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE AND INSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS 31 3.1.1. Powers and functions of Jozini municipality 31 3.1.2. Political structure 31 3.1.3. Management structure 35 3.1.4. Traditional Councils and their role 41 3.2. STATUS QUO ANALYSIS 42 3.2.1. Demographics 42 3.2.1.1. Age distribution 43 3.2.1.2. Dependancy ratio 44 3.2.1.3. Household income 46 3.2.1.4. Levels of education 47 3.3. SERVICE DELIVERY AND INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT 48 3.3.1. Water 48 3.3.2. -

APOSTOLIC VICARIATE of INGWVUMA, SOUTH AFRICA Description the Apostolic Vicariate of Ingwavuma Is in the Northeastern Part of the Republic of South Africa

APOSTOLIC VICARIATE OF INGWVUMA, SOUTH AFRICA Description The Apostolic Vicariate of Ingwavuma is in the northeastern part of the Republic of South Africa. It includes the districts of Ingwavuma, Ubombo and Hlabisa. The Holy See entrusted this territory to the Servite Order in 1938 and the Tuscan Province accepted the mandate to implant the Church in this area (implantatio ecclesiae). Bishop Costantino Barneschi, Vicar Apostolic of Bremersdorp (now Manzini) asked the American Province to send friars for the new mission. Fra Edwin Roy Kinch (1918-2003) arrived in Swaziland in 1947. Other friars came from the United States and the Apostolic Prefecture of Ingwavuma was born. On November 19, 1990 the territory became an Apostolic Vicariate. After the Second World War the missionary territory was assumed directly by the friars of the North American provinces. By a decree of the 1968 General Chapter the then existing communities were established as the Provincial Vicariate of Zululand, a dependency of the US Eastern Province. At present there are 10 Servite friars who are members of the Zululand Delegation OSM. Servites The friars of the Zululand delegation work in five communities: Hlabisa, Ingwavuma, KwaNgwanase, Mtubtuba and Ubombo; there are 9 solemn professed (2 local, 2 Canadian and 5 from the US). General Information Area: 12,369 sq km; population: 609,180; Catholics: 23,054; other denominations: Lutherans, Anglicans, Methodists: 150,000; African Churches 60,000; non-Christian: 300,000; parishes: 5; missionary stations: 68; 8 Servite priests and one local priest: Father Wilbert Mkhawanazi. Lay Missionaries: 3; part-time catechists: 160; full-time catechists: 9. -

Lithostratigraphy of Border Cave, Kwazulu, South Africa: a Middle Stone Age Sequence Beginning C

Journal oj Archaeological Science 1978, 5, 317-341 Lithostratigraphy of Border Cave, KwaZulu, South Africa: a Middle Stone Age Sequence Beginning c. 195,000 B.P. K. W. ButzeTa, P. B. Beaumontb and J. C. Vogel” Border Cave is well-known for its Middle Stone Age (MSA) sequence and associ- ated hominids, as well as for the earliest demonstrable Later Stone Age (LSA) (c. 38,000 b.p.) strata in southern Africa. Detailed lithostratigraphic and sedimento- logical study permits identification of 8 Pleistocene sedimentary cycles, including 6 major cold phases and 2 intervening weathering horizons. The 2 youngest cold phases are associated with the LSA and have 8 14C dates 38,600-13,300 b.p. By gauging sedimentation rates in finer and coarser sediments, duration of sedi- mentary breaks, and allowing for differential compaction, the excellent radiocarbon framework provided by 28 available 14C dates can be extrapolated to the 6 cold intervals and 2 palaeosols that are older than 50,000 b.p. These clearly span oxygen- isotope stages 4, 5 and 6, placing the base of the MSA deposits at c. 195,000 b.p., Homo sapiens sapiens at c. 90,000-115,000 b.p. and the sophisticated, microlithic “Howieson’s Poort” industry at 95,000 b.p. These results require radical reassess- ment of the age and nature of the MSA complex and of the earliest evolution of anatomically-modern people. Keywords: BORDER CAVE, CAVE SEDIMENTOLOGY, EBOULIS SECS, GEO-ARCHAEOLOGY, HOMO SAPIENS SAPIENS, ISOTOPE STRATI- GRAPHY, MIDDLE AND LATER STONE AGE, PALAEOCLIMATOLOGY, PALAEOSOLS, RADIOCARBON CHRONOLOGY. Introduction Border Cave first drew attention when fossilized human bone was uncovered by Mr W. -

Export This Category As A

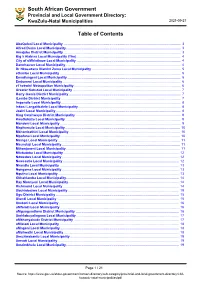

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory: KwaZulu-Natal Municipalities 2021-09-27 Table of Contents AbaQulusi Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Alfred Duma Local Municipality ........................................................................................................................... 3 Amajuba District Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Big 5 Hlabisa Local Municipality (The) ................................................................................................................ 4 City of uMhlathuze Local Municipality ................................................................................................................ 4 Dannhauser Local Municipality ............................................................................................................................ 4 Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma Local Municipality ................................................................................................ 5 eDumbe Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 5 Emadlangeni Local Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 6 Endumeni Local Municipality ..............................................................................................................................