Cannabis and the Gateway Effect June 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cannabis and the Developing Brain: Insights Into Its Long-Lasting Effects

8250 • The Journal of Neuroscience, October 16, 2019 • 39(42):8250–8258 Mini-Symposium Cannabis and the Developing Brain: Insights into Its Long-Lasting Effects Yasmin L. Hurd,1 XOlivier J. Manzoni,2 Mikhail V. Pletnikov,3 Francis S. Lee,4 Sagnik Bhattacharyya,5 and X Miriam Melis6 1Department of Psychiatry and Department of Neuroscience, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York 10029, 2Aix Marseille University, Institut National de la Sante´ et de la Recherche Me´dicale, Institut de neurobiologie de la méditerranée, 13273 Marseille, France, and Cannalab, Cannabinoids Neuroscience Research International Associated Laboratory, Institut National de la Sante´ et de la Recherche Me´dicale, 13273 Marseille, France, 3Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Solomon H. Snyder Department of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, 4Department of Psychiatry, Sackler Institute for Developmental Psychobiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York 10065, 5Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London SE5 8AF, United Kingdom, and 6Department of Biomedical Sciences, Division of Neuroscience and Clinical Pharmacology, University of Cagliari, 09042 Cagliari, Italy The recent shift in sociopolitical debates and growing liberalization of cannabis use across the globe has raised concern regarding its impact on vulnerable populations, such as pregnant women and adolescents. Epidemiological studies have long demonstrated a rela- tionship between developmental cannabis exposure and later mental health symptoms. This relationship is especially strong in people with particular genetic polymorphisms, suggesting that cannabis use interacts with genotype to increase mental health risk. Seminal animalresearchdirectlylinkedprenatalandadolescentexposuretodelta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol,themajorpsychoactivecomponentof cannabis, with protracted effects on adult neural systems relevant to psychiatric and substance use disorders. -

Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Oral Cannabidiol When Administered Concomitantly with Intravenous Fentanyl Rajita Sinha, Phd, Didier Jutras-Aswad, MD, MS, Marilyn A

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Oral Cannabidiol When Administered Concomitantly With Intravenous Fentanyl 08/15/2018 on BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3XI41p+sDLxYskzzWJHpwFPA3MvB4/FX5gh6vcjyLLl1kCfZEXLPTKQ== by https://journals.lww.com/journaladdictionmedicine from Downloaded in Humans Downloaded Alex F.Manini, MD, MS, Georgia Yiannoulos, MS, Mateus M. Bergamaschi, PhD, from Stephanie Hernandez, MD, MS, Ruben Olmedo, MD, Allan J. Barnes, BSc, Gary Winkel, PhD, https://journals.lww.com/journaladdictionmedicine Rajita Sinha, PhD, Didier Jutras-Aswad, MD, MS, Marilyn A. Huestis, PhD, and Yasmin L. Hurd, PhD Results: SAFTEE data were similar between groups without res- Objectives: Cannabidiol (CBD) is hypothesized as a potential treat- piratory depression or cardiovascular complications during any test ment for opioid addiction, with safety studies an important first step session. After low-dose CBD, tmax occurred at 3 and 1.5 hours in for medication development. We determined CBD safety and phar- by sessions 1 and 2, respectively. After high-dose CBD, tmax occurred at BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3XI41p+sDLxYskzzWJHpwFPA3MvB4/FX5gh6vcjyLLl1kCfZEXLPTKQ== macokinetics when administered concomitantly with a high-potency 3 and 4 hours in sessions 1 and 2, respectively. There were no signif- opioid in healthy subjects. icant differences in plasma CBD or cortisol (AUC P = NS) between Methods: This double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study of sessions. CBD, coadministered with intravenous fentanyl, was conducted at Conclusions: Cannabidiol does not exacerbate adverse effects asso- the Clinical Research Center in Mount Sinai Hospital, a tertiary care ciated with intravenous fentanyl administration. Coadministration of medical center in New York City. Participants were healthy volunteers CBD and opioids was safe and well tolerated. -

FDA Office of Women's Health US Food and Drug Administration

FDA OFFICE OF WOMEN’S HEALTH SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE CBD & Other Cannabinoids Sex and Gender Differences in Use and Responses Thursday, November 19, 2020 | 9:00 AM–4:00 PM EST Virtual Meeting CBD and Other Cannabinoids: Sex and Gender Differences in Use and Responses | 1 !/"'""'', 11 U.S. FOOD & DRUG •J ADMINISTRATION Dear Colleagues, On behalf of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) Office of Women's Health (OWH), I am pleased to welcome you to today's conference, "CBD and Other Cannabinoids: Sex and Gender Differences in Use and Responses." The mission of FDA is to protect and promote public health. A top priority for OWH is to identify and monitor emerging areas of interest and potential concern for the health of women. Cannabidiol (CBD) products are appearing everywhere - from medical cannabis dispensaries, to pharmacies, to gas stations. Many of these products are illegally marketed and purport to target a myriad of health concerns, including conditions more commonly experienced by women than men, such as chronic pain, sleep disturbances, anxiety and depression. Given that little is known about how and if many cannabis derived products work, how and why women are using them, and their potential associated risks, there is a mounting need to consolidate and communicate what we know about these products and to identify knowledge gaps. Further, the use of these products during pregnancy and lactation raises additional questions and concerns. The purpose of today's meeting is to highlight the needed and existing research to address the many "who", "what", and "why" questions surrounding products containing CBD and other cannabinoids. -

Internships in Behavioral Neuroscience 2010-2019(Opens In

Marymount Manhattan College Student Research/Internships/Independent Studies 2010-2019 Last updated 10/24/2019 All offsite research experiences listed, were actively pursued and coordinated by Deirtra-Hunter-Romagnoli to provide multiple opportunities for MMC students to work in renown academic research laboratories or professional clinical institutions across New York City. Research internship opportunities for students included working with stem cells, utilizing human and animal experimental protocols to learn more about neurological diseases like multiple sclerosis, alzheimers, addiction and how social hierarchies can influence psychological conditions. Emphasis was placed on neuroscience laboratories however when alternate laboratory opportunities presented themselves I was easily able to place MMC students from different disciplines. More recently, a growing number of students outside of the Natural Sciences Division have taken part in these research internship opportunities. Specifically, there has been an increase in the number of Theatre, Dance and Business students declaring a neuroscience minor and taking advantage of new research opportunities including options recently available at the MMC Music, Mind and Brain Behavioral Neuroscience Laboratory. Most research experiences culminated with students presenting final results at a professional research forum and some students also have published abstracts. All onsite research experiences and Independent study projects were supervised or co-supervised by Deirtra Hunter-Romagnoli. The following descriptions of coordinated research experiences are listed by academic year and a brief summary of the laboratory focus is included. When available current updates of student’s current professional trajectory/status are included. Academic Year 2018-2019 Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital: Neuroscience Department 1.Martine Faustin (Class of 2019) Worked in the Lab of Molecular Psychiatry with Dr. -

IBNS 2016 Program - Budapest, Hungary

IBNS 2016 Program - Budapest, Hungary Please note this is not the final program and is subject to change. Revised May 9, 2016 Tuesday, June 7 Council Meeting. 9:00-1:00 Tours. 1:00-6:00 Welcome Reception. 7:00-10:00 Student Social. 7:00-8:00 Wednesday, June 8 Sex differences in the brain: Implications for behavioral and biomedical research. Chair: Elena Choleris 8:00-8:30 Sex differences in rodent social behavior: Hormonal influences. Choleris, Elena; Clipperton- Allen, Amy; Ervin, Kelsy SJ; Lymer, Jennifer M; Gabor, Christopher S; Sheppard, Paul; Phan, Anna. 8:30-9:00 Sex matters: Hippocampal neurogenesis, Spatial Learning and Pattern Separation. Galea, Liisa A. M. 9:00-9:30 Estrogenic regulation of memory in males and females: Molecular mechanisms and implications for aging. Frick, Karyn M. 9:30-10:00 Sex differences in stroke and stroke therapies. Sohrabji, Farida. Epigenetic Regulation of Motivated Behaviors. Chair: Zuoxin Wang; Co-Chair: Mohamed Kabbaj 8:00-8:30 Role of DNA methyl-cytosine oxidation in cocaine action. Feng, Jian. 8:30-9:00 Methamphetamine-associated memory is regulated by histone methylation. Miller, Courtney A. 9:00-9:30 Influence of genomic imprinting on metabolism and behavior. Lu, Xin-Yun. 9:30-10:00 Epigenetics of Social Bonding in Prairie Voles. Kabbaj, Mohamed; Wang, Zuoxin; Liu, Yan; Elvir, Lindsay. Exhibits – Refreshment Break. 10:00-10:30 Keynote Speaker 10:30-11:30 High Times for Cannabis: Epigenetic Imprint and its Legacy on Brain and Behavior. Yasmin Hurd. Lunch. 11:30-1:30 Zebrafish and human brain disorders: A new tool in behavioral neuroscience. -

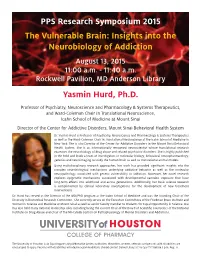

The Vulnerable Brain: Insights Into the Neurobiology of Addiction PPS

PPS Research Symposium 2015 The Vulnerable Brain: Insights into the Neurobiology of Addiction August 13, 2015 11:00 a.m. - 11:40 a.m. Rockwell Pavilion, MD Anderson Library Yasmin Hurd, Ph.D. Professor of Psychiatry, Neuroscience and Pharmacology & Systems Therapeutics, and Ward-Coleman Chair in Translational Neuroscience, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Director of the Center for Addictive Disorders, Mount Sinai Behavioral Health System Dr. Yasmin Hurd is Professor of Psychiatry, Neuroscience and Pharmacology & Systems Therapeutics as well as the Ward-Coleman Chair in Translational Neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine in New York. She is also Director of the Center for Addictive Disorders in the Mount Sinai Behavioral Health System. She is an internationally renowned neuroscientist whose translational research examines the neurobiology of drug abuse and related psychiatric disorders. She is highly published in the field and leads a team of investigators in molecular biology, behavioral neuropharmacology, genetics and neuroimaging to study the human brain as well as translational animal models. Using multidisciplinary research approaches, her work has provided significant insights into the complex neurobiological mechanisms underlying addictive behavior as well as the molecular neuropathology associated with genetic vulnerability to addiction. Moreover, her novel research explores epigenetic mechanisms associated with developmental cannabis exposure that have long-term effects into adulthood and across generations. Additionally, her basic science research is complimented by clinical laboratory investigations for the development of new treatment interventions. Dr. Hurd has served as the Director of the MD/PhD program at the Icahn School of Medicine and was the founding Chair of the Diversity in Biomedical Research Committee. -

Petition to Add Opioid Use Disorder to the List of Medical Conditions for the New Mexico Medical Cannabis Program Background

Petition to Add Opioid Use Disorder to the List of Medical Conditions for the New Mexico Medical Cannabis Program Background: This petition was submitted to the New Mexico Sec. of Health and presented to the Medical Advisory Board (MAB), a group of expert clinicians tasked with evaluating petitions. Board members overwhelmingly voted approval of the petition (5-1). The Secretary rejected the MAB’s recommendation and declined to add opioid use disorder to the list of qualifying conditions in June 2017. The petitioner plans to refile at the next opportunity. _____________________________________________________________________________________ Name of Person Filing Petition: Anita Briscoe Names of Witnesses Providing Technical Evidence: Steve Jenison, MD, Former Chair, Medical Cannabis Advisory Board Pam Conry, APRN BC, Psychiatric Nurse Practitioner Florian Birkmeyer, MD, Psychiatrist Ramon H, patient Michael V, patient Lisa Chavez, Case Manager, UNM Forensic Psychiatry Willie Ford, Director, R Greenleaf Dispensary Jeffery Holland, Director, Endorphin Power Company _____________________________________________________________________________________ PETITION TO THE NM MEDICAL ADVISORY BOARD TO THE NEW MEXICO MEDICAL CANNABIS PROGRAM TO ADD OPIATE DEPENDENCE AS A QUALIFYING CONDITION Anita Briscoe, MS, APRN-BC 718 Adams NE, Albuquerque, NM 87110 505-720-9495 My name is Anita Willard Briscoe and I am a native New Mexican from Espanola, living in Albuquerque. I have been a nurse for 40 years, a psych nurse practitioner for 12 years. I have been referring patients to the cannabis program for 7 years. Over this past year I have observed that about 25% of my patients have stated independently that they were able to kick opiates with cannabis. They state it calms down their cravings, relaxes their craving anxiety and is helping them to keep off of opiates. -

UPDATE - New York City Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Renowned Global Researcher Dr

May 23, 2019 UPDATE - New York City Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Renowned Global Researcher Dr. Hurd, Select MediPharm Labs to Support 500 Patient Major Clinical Study And “CBD International Consortium” to Develop Treatment of Opioid Addiction MediPharm Labs enters major U.S. led opioid clinical research trial to develop IP and exclusively manufacture CBD gelcaps TORONTO, May 23, 2019 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) --M ediPharm Labs Corp. (TSXV: LABS) (OTCQX: MEDIF) (FSE:MLZ) (“MediPharm Labs”) a leader in specialized, research-driven cannabis extraction and cannabinoid isolation, is pleased to announce it has been selected by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York City (“Icahn School of Medicine”), to participate in a clinical trial dedicated to developing a non-addictive oral gelcap medication for the treatment of opioid use disorder through anti-anxiety intervention utilizing hemp-derived CBD combined with a proprietary formula (the “Formula”). This will be a U.S. and international large-scale, multi-site clinical trial that will include at least 500 patients spanning the United States, Canada, Australia, Europe and Jamaica. The clinical trial will be led by renowned principal researcher, Dr. Yasmin L. Hurd, PhD, the Ward-Coleman Chair of Translational Neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and Director of the Addiction Institute at Mount Sinai and the Center for Addictive Disorders for the Mount Sinai Behavioral Health System. MediPharm Labs is also pleased to be involved in the clinical trial, directed by Icahn School of Medicine, with Courtney Betty of Timeless Herbal Care Inc. (“Timeless Herbal”), a fully integrated licensed producer of medicinal cannabis in Jamaica. -

Opioid Relapse Takes Initial Center Stage

7/21/2019 Early Phase in the Development of Cannabidiol as a Treatment for Addiction: Opioid Relapse Takes Initial Center Stage Neurotherapeutics. 2015 Oct; 12(4): 807–815. PMCID: PMC4604178 Published online 2015 Aug 13. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0373-7 PMID: 26269227 Early Phase in the Development of Cannabidiol as a Treatment for Addiction: Opioid Relapse Takes Initial Center Stage Yasmin L. Hurd,1 Michelle Yoon,1 Alex F. Manini,2 Stephanie Hernandez,2 Ruben Olmedo,2 Maria Ostman,3 and Didier Jutras-Aswad4 1Departments of Psychiatry, Neuroscience and Pharmacology and Systems Therapeutics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY USA 2Division of Medical Toxicology, Department of Emergency Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY USA 3Department of Psychiatry, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden 4Research Center, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, Department of Psychiatry, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Canada Yasmin L. Hurd, Email: [email protected]. Corresponding author. Copyright © The American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, Inc. 2015 Abstract Multiple cannabinoids derived from the marijuana plant have potential therapeutic benefits but most have not been well investigated, despite the widespread legalization of medical marijuana in the USA and other countries. Therapeutic indications will depend on determinations as to which of the multiple cannabinoids, and other biologically active chemicals that are present in the marijuana plant, can be developed to treat specific symptoms and/or diseases. Such insights are particularly critical for addiction disorders, where different phytocannabinoids appear to induce opposing actions that can confound the development of treatment interventions. Whereas Δ9 -tetracannabinol has been well documented to be rewarding and to enhance sensitivity to other drugs, cannabidiol (CBD), in contrast, appears to have low reinforcing properties with limited abuse potential and to inhibit drug-seeking behavior. -

Opioid Relapse Takes Initial Center Stage

Neurotherapeutics (2015) 12:807–815 DOI 10.1007/s13311-015-0373-7 REVIEW Early Phase in the Development of Cannabidiol as a Treatment for Addiction: Opioid Relapse Takes Initial Center Stage Yasmin L. Hurd1 & Michelle Yoon1 & Alex F. Manini2 & Stephanie Hernandez2 & Ruben Olmedo2 & Maria Ostman3 & Didier Jutras-Aswad4 Published online: 13 August 2015 # The American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, Inc. 2015 Abstract Multiple cannabinoids derived from the marijuana and CBD’s efficacy at different phases of the abuse cycle for plant have potential therapeutic benefits but most have not different classes of addictive substances remain largely been well investigated, despite the widespread legalization understudied. Our paper provides an overview of preclinical of medical marijuana in the USA and other countries. Thera- animal and human clinical investigations, and presents prelimi- peutic indications will depend on determinations as to which nary clinical data that collectively sets a strong foundation in of the multiple cannabinoids, and other biologically active support of the further exploration of CBD as a therapeutic inter- chemicals that are present in the marijuana plant, can be de- vention against opioid relapse. As the legal landscape for medical veloped to treat specific symptoms and/or diseases. Such in- marijuana unfolds, it is important to distinguish it from Bmedical sights are particularly critical for addiction disorders, where CBD^ and other specific cannabinoids, that can more appropri- different phytocannabinoids appear to induce opposing ac- ately be used to maximize the medicinal potential of the tions that can confound the development of treatment inter- marijuana plant. ventions. Whereas Δ9-tetracannabinol has been well docu- mented to be rewarding and to enhance sensitivity to other Keywords THC . -

On the Shoulders of Giants Scientific Symposium

ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS SCIENTIFIC SYMPOSIUM Celebrating W. Thomas Boyce, MD Professor Emeritus Lisa and John Pritzker Distinguished Professor of Developmental Health at the University of California, San Francisco Recipient of the 2020 Sarah Gund Prize for Research and Mentorship in Child Mental Health Tuesday, October 6, 2020 5 PM – 8 PM EST Welcome Welcome to our 10th annual On the Shoulders of Giants Scientific Symposium, the Child Mind Institute’s celebration of scientific achievement in child and adolescent psychiatry, psychology and developmental neuroscience. The symposium pays tribute to the winner of the Child Mind Institute’s Sarah Gund Prize for Research and Mentorship in Child Mental Health. The award is given each year to a leader in the field chosen by our Scientific Research Council for outstanding contributions to our understanding of the brain and behavior and dedication to scientific collaboration and mentorship. 2 Child Mind Institute Program PART ONE: AWARDS AND PRESENTATIONS 5-6:30 PM EDT Welcome and Opening Remarks Harold S. Koplewicz, MD, President, Child Mind Institute Sarah Gund Prize for Research and Mentorship in Child Mental Health Presentation Sarah Gund, Psychoeducational Clinician Presentations The Tenderness of Childhood: Orchids, Dandelions, and the Intergenerationality of Developmental Science Tom Boyce, MD, Professor Emeritus, Lisa and John Pritzker Distinguished Professor of Developmental Health at the University of California, San Francisco, Recipient of the 2020 Sarah Gund Prize for Research and Mentorship in Child Mental Health Biological Embedding of Early Life Stress: Intergenerational Transmission, Reversibility, and Resilience Nicole Bush, PhD, Associate Professor, University of California, San Francisco From risk to resilience: Leveraging developmental science to improve the lives of adversity-exposed families. -

Identifying Distinct Striatonigral and Striatopallidal Disturbances After

2019 Cannabinoids in Clinical Practice conference March 21-22, 2019 DISCLOSURES Anahita Bassir Nia Henrietta Szutorisz Noel Warren Jacqueline Ferland Anissa Bara Gregory Rompala Tanni Rahman Diana Akpoyibo Randy Ellis Claire Mann Natasha Berryman Gabor Egervari Michael Miller Yasmin Hurd Director, Addiction Institute, Mount Sinai Behavioral Health System Departments of Psychiatry and Neuroscience Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Joseph Landry Nayana Patel James Callens Teddy Uzamere Anna Oprescu Annie Ly Sharron Spriggs New York City • No financial disclosure • GW Pharmaceuticals – medication for clinical trial 0 1 Relationship between opioid prescribing rate (per 1,000 Wonder drug OPDP-eligible population) and opioid-related mortality rate (per 100,000 population) among Ontario counties 3400 B.C., when the Sumerians in lower Mesopotamia were cultivating the opium poppy, known as “Hul Gil”—the “Joy Plant.” Opium was~220 used-264 by A.D., many the ancient noted Chinese cultures—surgeonthe Assyrians, Hua To Egyptians,of the Three Arabs, Greeks,Kingdoms Romans, used opiumand Chinese.preparationsBy and1527 Cannabis, the Swiss indica-German for his patientsalchemist to swallow Paracelus beforehad undergoingintroduced major surgery. the use of opium pills 1806, German chemist Friedrich Wilhelm in medicine Adam Sertürner isolated morphine from opium, namedMorphine after the became Ancient a Greekmainstay in U.S. “god of dreams,”medical Morpheus. treatment throughout the 19th century for pain, anxiety, respiratory problems, “consumption,” “women’s ailments.”Heroin was then synthesized in 1898 by Bayer as a cough suppressant and “non-addictive” morphine substitute for medical1914 use., the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act essentially prohibited prescription opioids; In 1924, The Heroin Act made the drug 1916 German scientists synthesized illegal even for medical use.