Shakespeare's Isabella and Cressida on the Modern Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

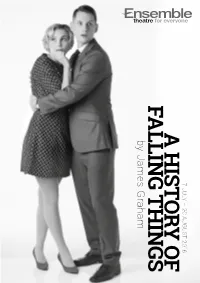

A H Ist Or Y of Fa Llin G T H In

7 JULY – 20 AUGUST 2016 A HISTORY OF FALLING THINGS by James Graham A HISTORY OF FALLING THINGS by James Graham PLAYWRIGHT DIRECTOR JAMES GRAHAM NICOLE BUFFONI CAST CREW ROBIN JACQUI DESIGNER ASSISTANT ERIC BEECROFT SOPHIE HENSSER ANNA GARDINER STAGE MANAGER SLADE BLANCH LIGHTING LESLEY REECE DESIGNER WARDROBE MERRIDY BRIAN MEEGAN CHRISTOPHER PAGE COORDINATOR EASTMAN RENATA BESLIK AV DESIGNER JIMMY TIM HOPE DIALECT SAM O’SULLIVAN COACH SOUND DESIGNER NICK CURNOW ALISTAIR WALLACE JOHN REHEARSAL (VOICEOVER) STAGE OBSERVER MARK KILMURRY MANAGER ELSIE EDGERTON-TILL LARA QUALTROUGH PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY RUNNING TIME: APPROXIMATELY 90 MINUTES (NO INTERVAL) JAMES GRAHAM – PLAYWRIGHT James is a playwright and film Barlow. It opened in Boston in Summer 2014 and and television writer who won transferred to Broadway in Spring 2015. His play the Pearson Playwriting Bursary THE VOTE at the Donmar Warehouse aired in real in 2006 and went on to win the time on TV in the final 90 minutes of the 2015 Catherine Johnson Award for the Best Play in polling day and has been nominated for a BAFTA. 2007 for his play EDEN’S EMPIRE. James’ play His first film for television, CAUGHT IN A TRAP, was THIS HOUSE premièred at the Cottesloe Theatre broadcast on ITV1 on Boxing Day 2008. James was in September 2012, directed by Jeremy Herrin, and picked as one of Broadcast Magazine’s Hotshots transferred to the Olivier in 2013 where it enjoyed in the same year. He is developing original series a sell out run and garnered critical acclaim and and adaptations with Tiger Aspect, Leftbank, a huge amount of interest and admiration from Kudos and the BBC. -

Laura Morrod Resume

LAURA MORROD – Editor FATE Director: Lisa James Larsson. Producer: Macdara Kelleher. Starring: Abigail Cowen, Danny Griffin and Hannah van der Westhuysen. Archery Pictures / Netflix. LOVE SARAH Director: Eliza Schroeder. Producer: Rajita Shah. Starring: Grace Calder, Rupert Penry-Jones, Bill Paterson and Celia Imrie. Miraj Films / Neopol Film / Rainstar Productions. THE LAST KINGDOM (Series 4) Director: Sarah O’Gorman. Producer: Vicki Delow. Starring: Alexander Dreymon, Ian Hart, David Dawson and Eliza Butterworth. Carnival Film & Television / Netflix. THE FEED Director: Jill Robertson. Producer: Simon Lewis. Starring: Guy Burnet, Michelle Fairlye, David Thewlis and Claire Rafferty. Amazon Studios. ORIGIN Director: Mark Brozel. Executive Producers: Rob Bullock, Andy Harries and Suzanne Mackie. Producer: John Phillips. Starring: Tom Felton, Philipp Christopher and Adelayo Adedayo. Left Bank Pictures. THE GOOD KARMA HOSPITAL 2 Director: Alex Winckler. Producer: John Chapman. Starring: Amanda Redman, Amrita Acharia and Neil Morrissey. Tiger Aspect Productions. THE BIRD CATCHER Director: Ross Clarke. Producers: Lisa Black, Leon Clarance and Ross Clarke. Starring: August Diehl, Sarah-Sofie Boussnina and Laura Birn. Motion Picture Capital. BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN: IN HIS OWN WORDS Director: Nigel Cole. Producer: Des Shaw. Starring: Bruce Springsteen. Lonesome Pine Productions. 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] HUMANS (Series 2) Director: Mark Brozel. Producer: Paul Gilbert. Starring: Gemma Chan, Colin Morgan and Emily Berrington. Kudos Film and Television. AFTER LOUISE Director: David Scheinmann. Producers: Fiona Gillies, Michael Muller and Raj Sharma. Starring: Alice Sykes and Greg Wise. Scoop Films. DO NOT DISTURB Director: Nigel Cole. Producer: Howard Ella. Starring: Catherine Tate, Miles Jupp and Kierston Wareing. -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

March 19, 2013 (XXVI:9) Mike Leigh, NAKED (1994, 131 Min.)

March 19, 2013 (XXVI:9) Mike Leigh, NAKED (1994, 131 min.) Best Director (Leigh), Best Actor (Thewliss), Cannes 1993 Directed and written by Mike Leigh Written by Mike Leigh Produced by Simon Channing Williams Original Music by Andrew Dickson Cinematography by Dick Pope Edited by Jon Gregory Production Design by Alison Chitty Art Direction by Eve Stewart Costume Design by Lindy Hemming Steadicam operator: Andy Shuttleworth Music coordinator: Step Parikian David Thewlis…Johnny Lesley Sharp…Louise Clancy Jump, 2010 Another Year, 2008 Happy-Go-Lucky, 2004 Vera Katrin Cartlidge…Sophie Drake, 2002 All or Nothing, 1999 Topsy-Turvy, 1997 Career Girls, Greg Cruttwell…Jeremy G. Smart 1996 Secrets & Lies, 1993 Naked, 1992 “A Sense of History”, Claire Skinner…Sandra 1990 Life Is Sweet, 1988 “The Short & Curlies”, 1988 High Hopes, Peter Wight…Brian 1985 “Four Days in July”, 1984 “Meantime”, 1982 “Five-Minute Ewen Bremner…Archie Films”, 1973-1982 “Play for Today” (6 episodes), 1980 BBC2 Susan Vidler…Maggie “Playhouse”, 1975-1976 “Second City Firsts”, 1973 “Scene”, and Deborah MacLaren…Woman in Window 1971 Bleak Moments/ Gina McKee…Cafe Girl Carolina Giammetta…Masseuse ANDREW DICKSON 1945, Isleworth, London, England) has 8 film Elizabeth Berrington…Giselle composition credits: 2004 Vera Drake, 2002 All or Nothing, 1996 Darren Tunstall…Poster Man Secrets & Lies, 1995 Someone Else's America, 1994 Oublie-moi, Robert Putt...Chauffeur 1993 Naked, 1988 High Hopes, and 1984 “Meantime.” Lynda Rooke…Victim Angela Curran...Car Owner DICK POPE (1947, Bromley, -

Completeandleft Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F

MEN WOMEN 1. FA Frankie Avalon=Singer, actor=18,169=39 Fiona Apple=Singer-songwriter, musician=49,834=26 Fred Astaire=Dancer, actor=30,877=25 Faune A.+Chambers=American actress=7,433=137 Ferman Akgül=Musician=2,512=194 Farrah Abraham=American, Reality TV=15,972=77 Flex Alexander=Actor, dancer, Freema Agyeman=English actress=35,934=36 comedian=2,401=201 Filiz Ahmet=Turkish, Actress=68,355=18 Freddy Adu=Footballer=10,606=74 Filiz Akin=Turkish, Actress=2,064=265 Frank Agnello=American, TV Faria Alam=Football Association secretary=11,226=108 Personality=3,111=165 Flávia Alessandra=Brazilian, Actress=16,503=74 Faiz Ahmad=Afghan communist leader=3,510=150 Fauzia Ali=British, Homemaker=17,028=72 Fu'ad Aït+Aattou=French actor=8,799=87 Filiz Alpgezmen=Writer=2,276=251 Frank Aletter=Actor=1,210=289 Frances Anderson=American, Actress=1,818=279 Francis Alexander+Shields= =1,653=246 Fernanda Andrade=Brazilian, Actress=5,654=166 Fernando Alonso=Spanish Formula One Fernanda Andrande= =1,680=292 driver.=63,949=10 France Anglade=French, Actress=2,977=227 Federico Amador=Argentinean, Actor=14,526=48 Francesca Annis=Actress=28,385=45 Fabrizio Ambroso= =2,936=175 Fanny Ardant=French actress=87,411=13 Franco Amurri=Italian, Writer=2,144=209 Firoozeh Athari=Iranian=1,617=298 Fedor Andreev=Figure skater=3,368=159 ………… Facundo Arana=Argentinean, Actor=59,952=11 Frickin' A Francesco Arca=Italian, Model=2,917=177 Fred Armisen=Actor=11,503=68 Frank ,Abagnale ,Criminal ,Catch Me If You Can François Arnaud=French Canadian actor=9,058=86 Ferhat ,Abbas ,Head of State ,President of Algeria, 1962-63 Fábio Assunção=Brazilian actor=6,802=99 Floyd ,Abrams ,Attorney ,First Amendment lawyer COMPLETEandLEFT Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F. -

Max Bruch Symphonies 1–3 Overtures Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino

Max Bruch Symphonies 1–3 Overtures Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 1 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Max Bruch, 1870 cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 2 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Max Bruch (1838–1920) Complete Symphonies CD 1 Symphony No. 1 op. 28 in E flat major 38'04 1 Allegro maestoso 10'32 2 Intermezzo. Andante con moto 7'13 3 Scherzo. Presto 5'00 4 Quasi Fantasia. Grave 7'30 5 Finale. Allegro guerriero 7'49 Symphony No. 2 op. 36 in F minor 39'22 6 Allegro passionato, ma un poco maestoso 15'02 7 Adagio ma non troppo 13'32 8 Allegro molto tranquillo 10'57 T.T.: 77'30 cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 3 13.03.2020 10:56:27 CD 2 1 Prelude from Hermione op. 40 8'54 (Concert ending by Wolfgang Jacob) 2 Funeral march from Hermione op. 40 6'15 3 Entr’acte from Hermione op. 40 2'35 4 Overture from Loreley op. 16 4'53 5 Prelude from Odysseus op. 41 9'54 Symphony No. 3 op. 51 in E major 38'30 6 Andante sostenuto 13'04 7 Adagio ma non troppo 12'08 8 Scherzo 6'43 9 Finale 6'35 T.T.: 71'34 Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino, Conductor cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 4 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Bamberger Symphoniker (© Andreas Herzau) cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 5 13.03.2020 10:56:28 Auf Eselsbrücken nach Damaskus – oder: darüber, daß wir es bei dieser Krone der Schöpfung Der steinige Weg zu Bruch dem Symphoniker mit einem Kompositum zu tun haben, das sich als Geist mit mehr oder minder vorhandenem Verstand in einem In der dichtung – wie in aller kunst-betätigung – ist jeder Körper darstellt (die Bezeichnungen der Ingredienzien der noch von der sucht ergriffen ist etwas ›sagen‹ etwas ›wir- mögen wechseln, die Tatsache bleibt). -

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time Embarks on a Third Uk and Ireland Tour This Autumn

3 March 2020 THE NATIONAL THEATRE’S INTERNATIONALLY-ACCLAIMED PRODUCTION OF THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME EMBARKS ON A THIRD UK AND IRELAND TOUR THIS AUTUMN • TOUR INCLUDES A LIMITED SEVEN WEEK RUN AT THE TROUBADOUR WEMBLEY PARK THEATRE FROM WEDNESDAY 18 NOVEMBER 2020 Back by popular demand, the Olivier and Tony Award®-winning production of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time will tour the UK and Ireland this Autumn. Launching at The Lowry, Salford, Curious Incident will then go on to visit to Sunderland, Bristol, Birmingham, Plymouth, Southampton, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Dublin, Belfast, Nottingham and Oxford, with further venues to be announced. Curious Incident will also play for a limited run in London at Troubadour Wembley Park Theatre in Brent - London Borough of Culture 2020 - following the acclaimed run of War Horse in 2019. Curious Incident has been seen by more than five million people worldwide, including two UK tours, two West End runs, a Broadway transfer, tours to the Netherlands, Canada, Hong Kong, Singapore, China, Australia and 30 cities across the USA. Curious Incident is the winner of seven Olivier Awards including Best New Play, Best Director, Best Design, Best Lighting Design and Best Sound Design. Following its New York premiere in September 2014, it became the longest-running play on Broadway in over a decade, winning five Tony Awards® including Best Play, six Drama Desk Awards including Outstanding Play, five Outer Critics Circle Awards including Outstanding New Broadway Play and the Drama League Award for Outstanding Production of a Broadway or Off Broadway Play. -

Monday, November 27 | 7:30 Pm

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 27 | 7:30 PM ALSO INSIDE This month, artists-in-residence Kontras Quartet explore the folk roots of classical music; on Live from WFMT, Kerry Frumkin welcomes the young string artists of the Dover Quartet and the acclaimed new-music ensemble eighth blackbird. Air Check Dear Member, The Guide Geoffrey Baer’s distinguished on-camera career at WTTW began in 1995 with the very first Chicago The Member Magazine for River Tour. A decade later, he took audiences back to that familiar territory to highlight big changes WTTW and WFMT Renée Crown Public Media Center that had taken place along its banks. Now, 12 years later, Geoffrey returns with an all-new tour that 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue covers more ground – all three branches of the river, in six different vessels, and the development Chicago, Illinois 60625 along the Chicago Riverwalk! Join him on WTTW11 and at wttw.com/river as Geoffrey shows us the incredible transformation that has taken place Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 over the past decade – not just in the architecture but in how Chicagoans Member and Viewer Services enjoy it. Along the way, he shares fascinating stories about the River’s history, (773) 509-1111 x 6 and introduces some memorable characters who live, work, and play there. WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 Also this month on WTTW11 and wttw.com/watch, join us for the Chicago Production Center premiere of another exciting new local film and its companion website, (773) 583-5000 Making a New American NUTCRACKER, a collaboration with The Joffrey Websites Ballet that goes behind the scenes of a new interpretation of Tchaikovsky’s wttw.com classic holiday favorite. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Catalogue 2013

Evropa Film Akt et L’AAFEE présentent L’Europe autour de l’Europe Festival de films européens 8ème édition Mémoire et devenir Du 13 mars au 14 avril 2013 Cinéma l’Entrepôt Auditorium Jean XXIII Centre Culturel Irlandais Centre Culturel de Serbie Centre Culturel Italien Cité Nationale de l’Histoire de l’Immigration Door Studio Institut Hongrois de Paris / Cinéma V4 Fondation Hippocrène Galerie Italienne Goethe-Institut de Paris Institut Culturel Italien de Paris L’Adresse Musée de La Poste La Filmothèque du Quartier Latin La Pagode Le Musée du Montparnasse Maison d’Europe et d’Orient Maison des Associations du 14e Moulin d’Andé Studio des Ursulines www.evropafilmakt.com Direction et sélection – Irena Bilić Coordination générale – Magdalena Petrović Vermeulen Production et logistique – Pablo Gleason González • Liste de diffusion et newsletter – Yvan Fischer • Assistant communication – Mauro Zanon • Coordination invités – Ivanka Polchenko Myers • Assistant Antoine Gilloire Attachées de presse / Promotion – Les Piquantes Documentation, site et catalogue – Marie-Noëlle Vallet assistée de Ivanka Polchenko Myers et Pablo Gleason • Traduction et sous-titrage – Marie-Noëlle Vallet, François Minaudier, Irena Bilić • Sous-titrage électronique – VOSTAO Designer – Julia Kosmynina • Conception graphique – Studio Shweb • Web-master – Alexandre Grebenkov Création statuette Prix Sauvage – Anđela Grabež Coordination Irlande – Sheila Pratschke Allemagne – Gisela Rueb • Azerbaïdjan – Eliza Pieter et Christine Blumauer • Danemark – Gitte Neergård Delcourt -

ANNE BARTON Anne Barton 1933–2013

ANNE BARTON Anne Barton 1933–2013 IN 1953 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, then, as now, one of the two leading academic Shakespeare journals in the world, published an article concisely titled ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’.1 The list of contributors identified the author as ‘Miss Bobbyann Roesen, a Senior at Bryn Mawr’, who ‘is the first under- graduate to contribute an essay to Shakespeare Quarterly. She attended the Shakespeare Institute at Stratford-upon-Avon in the summer of 1952 and hopes to pursue graduate studies in Renaissance literature at Oxford or Cambridge.’2 Looking back forty years later, the former Miss Roesen, now Anne Barton, had ‘a few qualms and misgivings’ about reprinting the article in a collection of some of her pieces. As usual, her estimate of her own work was accurate, if too modest: As an essay drawing fresh attention to a play extraordinarily neglected or mis- represented before that date, it does not seem to me negligible. Both its high estimate of the comedy and the particular reading it advances are things in which I still believe. But, however influential it may have been, it is now a period piece, written in a style all too redolent of a youthful passion for Walter Pater.3 Undoubtedly influential and far from negligible, the article not only continues to read well, for all its Paterisms, but also continues to seem an extraordinary accomplishment for an undergraduate. There is, through- out, a remarkable ability to close-read Shakespeare carefully and with sus- tained sensitivity, to see how the language is working on the page and how 1 Bobbyann Roesen, ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’, Shakespeare Quarterly, 4 (1953), 411–26. -

When Did You Last See Your Father?

WHEN DID YOU LAST SEE YOUR FATHER? Directed by Anand Tucker Starring Colin Firth Jim Broadbent Juliet Stevenson Official Selection 2007 Toronto International Film Festival East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Ziggy Kozlowski Leila Guenancia 853 7th Ave, 3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 212-247-2948 fax 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax Visit the website at: www.whendidyoulastseeyourfathermovie.com Short Synopsis When Did You Last See Your Father? is an unflinching exploration of a father/son relationship, as Blake Morrison deals with his father Arthur’s terminal illness and imminent death. Blake’s memories of everything funny, embarrassing and upsetting about his childhood and teens are interspersed with tender and heart- rending scenes in the present, as he struggles to come to terms with his father, and their history of conflict, and learns to accept that one’s parents are not always accountable to their children. Directed by Anand Tucker (Hilary and Jackie), from a screenplay by David Nicholls, adapted from Blake Morrison’s novel of the same name, the film stars Colin Firth, Jim Broadbent, Juliet Stevenson, Gina McKee, Claire Skinner, and Matthew Beard. Long Synopsis Arthur Morrison (Jim Broadbent), and his wife Kim (Juliet Stevenson), are doctors in the same medical practice in the heart of the Yorkshire Dales, England. They have two children, Gillian (Claire Skinner), and her older brother Blake (Colin Firth)Blake is a forty - year-old established author, married with two children and confronted with the fact that his father is terminally ill.