Zephyrus Western Kentucky University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

An Exploratory Investigation of the Exit Process Among Street-Level Prostituted Women

Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30 (2006), 276–290. Blackwell Publishing, Inc. Printed in the USA. Copyright C 2006 Division 35, American Psychological Association. 0361-6843/06 “YOU CAN’T HUSTLE ALL YOUR LIFE”: AN EXPLORATORY INVESTIGATION OF THE EXIT PROCESS AMONG STREET-LEVEL PROSTITUTED WOMEN Rochelle L. Dalla University of Nebraska–Lincoln Between 1998 and 1999, 43 street-level prostituted women were interviewed regarding their developmental experiences, including prostitution entry, maintenance, and exit attempts. Three years later, 18 of the original 43 participants were located and interviewed. This exploratory follow-up investigation focused on the women’s life experiences between the two points of contact, with emphasis on sex-industry exit attempts. Five women had maintained their exit efforts and had not returned to prostitution, nine had returned to both prostitution and drug use, and one had returned to prostitution only. Three additional women had violated parole and been reincarcerated. Themes evident among those who were able to stay out of prostitution and refrain from substance use are compared to those whose exit attempts had not been successful. Suggestions for intervention and outreach are presented, as are directions for future work. Prostitution activities and the contexts in which prostituted 1994), chemical dependence typically motivates contin- women work and survive are far from homogenous. Com- ued involvement (Flowers, 1998; Inciardi, Lockwood, & pared to other prostitution venues, such as escort services, Pottieger, 1993). street-level sex work is much more dangerous, with less Leaving the sex industry is a process, not an event monetary return (Maher, 1996; Miller, 1993). The past (M˚ansson & Hedin, 1999; Williamson & Folaron, 2003). -

Total Tracks Number: 1108 Total Tracks Length: 76:17:23 Total Tracks Size: 6.7 GB

Total tracks number: 1108 Total tracks length: 76:17:23 Total tracks size: 6.7 GB # Artist Title Length 01 00:00 02 2 Skinnee J's Riot Nrrrd 03:57 03 311 All Mixed Up 03:00 04 311 Amber 03:28 05 311 Beautiful Disaster 04:01 06 311 Come Original 03:42 07 311 Do You Right 04:17 08 311 Don't Stay Home 02:43 09 311 Down 02:52 10 311 Flowing 03:13 11 311 Transistor 03:02 12 311 You Wouldnt Believe 03:40 13 A New Found Glory Hit Or Miss 03:24 14 A Perfect Circle 3 Libras 03:35 15 A Perfect Circle Judith 04:03 16 A Perfect Circle The Hollow 02:55 17 AC/DC Back In Black 04:15 18 AC/DC What Do You Do for Money Honey 03:35 19 Acdc Back In Black 04:14 20 Acdc Highway To Hell 03:27 21 Acdc You Shook Me All Night Long 03:31 22 Adema Giving In 04:34 23 Adema The Way You Like It 03:39 24 Aerosmith Cryin' 05:08 25 Aerosmith Sweet Emotion 05:08 26 Aerosmith Walk This Way 03:39 27 Afi Days Of The Phoenix 03:27 28 Afroman Because I Got High 05:10 29 Alanis Morissette Ironic 03:49 30 Alanis Morissette You Learn 03:55 31 Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know 04:09 32 Alaniss Morrisete Hand In My Pocket 03:41 33 Alice Cooper School's Out 03:30 34 Alice In Chains Again 04:04 35 Alice In Chains Angry Chair 04:47 36 Alice In Chains Don't Follow 04:21 37 Alice In Chains Down In A Hole 05:37 38 Alice In Chains Got Me Wrong 04:11 39 Alice In Chains Grind 04:44 40 Alice In Chains Heaven Beside You 05:27 41 Alice In Chains I Stay Away 04:14 42 Alice In Chains Man In The Box 04:46 43 Alice In Chains No Excuses 04:15 44 Alice In Chains Nutshell 04:19 45 Alice In Chains Over Now 07:03 46 Alice In Chains Rooster 06:15 47 Alice In Chains Sea Of Sorrow 05:49 48 Alice In Chains Them Bones 02:29 49 Alice in Chains Would? 03:28 50 Alice In Chains Would 03:26 51 Alien Ant Farm Movies 03:15 52 Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 03:41 53 American Hifi Flavor Of The Week 03:12 54 Andrew W.K. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Got Me Wrong

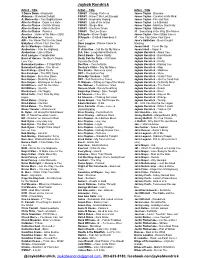

Jaykob Kendrick Artist - Title Artist - Title Artist - Title 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite CSN&Y - Change Partners James Taylor - Blossom Alabama – Dixieland Delight CSN&Y - Haven't We Lost Enough James Taylor - Carolina in My Mind A. Morissette – You Oughta Know CSN&Y - Helplessly Hoping James Taylor - Fire and Rain Alice in Chains - Down in a Hole CSN&Y - Lady of the Island James Taylor - Lo & Behold Alice in Chains - Got Me Wrong CSN&Y - Simple Man James Taylor - Machine Gun Kelly Alice in Chains - Man in the Box CSN&Y - Southern Cross James Taylor - Millworker Alice in Chains - Rooster CSN&Y - The Lee Shore JT - Something in the Way She Moves America – Horse w/ No Name ($20) D’Angelo – Brown Sugar James Taylor - Sweet Baby James Amy Winehouse – Valerie D’Angelo – Untitled (How does it JT - You Can Close Your Eyes AW – You Know That I’m No Good feel?) Jane's Addiction - Been Caught Babyface - When Can I See You Dave Loggins - Please Come to Stealing Arctic Monkeys - Arabella Boston Jason Isbell – Cover Me Up Audioslave - I Am the Highway D. Allan Coe - Call Me By My Name Jason Isbell – Super 8 Audioslave - Like a Stone D.A. Coe - Long-Haired Redneck Jaykob Kendrick - About You Avril Lavigne - Complicated David Bowie - Space Oddity Jaykob Kendrick - Barrelhouse Band of Horses - No One's Gonna Death Cab for Cutie – I’ll Follow Jaykob Kendrick - Fall Love You You into the Dark Jaykob Kendrick - Firefly Barenaked Ladies – If I had $1M Des’Ree – You Gotta Be Jaykob Kendrick - Kissing You Barenaked Ladies - One Week Destiny’s Child – Say My Name Jaykob Kendrick - Map Ben E King – Stand By Me Dire Straits - Romeo & Juliet Jaykob Kendrick - Medicine Ben Erickson - The BBQ Song DBT – Decoration Day Jaykob Kendrick - Muse Ben Harper - Burn One Down Drive-By Truckers - Outfit Jaykob Kendrick - Nuckin' Futs Ben Harper - Steal My Kisses DBT - Self-Destructive Zones Jaykob Kendrick – On the Good Foot Ben Harper - Waiting on an Angel D. -

Wedding Ceremony Classical Favourites Charts 50'S, 60'S, 70'S

W edding Ceremony Classical Favourites Charts 50’s, 60’s, 70’s, 80’s Charts 90’s, 00’s, Now Christmas Classical Film and TV Jazz, Rags and Tangos Opera and Ballet Scottish & Irish Traditional Video Game Soundtracks ___________ EMAIL | FACEBOOK | TWITTER | YOUTUBE | INSTAGRAM © 2018. The Cairn String Quartet. All Rights Reserved Wedding Ceremony Classical Favourites BACK TO MENU A Thousand Years / Christina Perry Air on a G String / Bach All about You / McFly Ave Maria / Beyonce, Schubert and Gounod Canon / Pachelbel Caledonia / Dougie McLean For the Love of a Princess / Secret Wedding / Braveheart Here Come the Girls turning into Pachelbel’s Canon / Sugababes / Pachelbel Highland Cathedral I Giorno / Einaudi Kissing You / From Romeo and Juliet One Day Like this / Elbow The Final Countdown / Europe Wedding March / Wagner Wedding March / Mendelssohn Wedding March turning into Star Wars / Mendelssohn / Star Wars Wedding March turning into All you Need is Love / Mendelssohn / Beatles Wedding March turning into Another One Bites the Dust / Mendelssohn / Queen Wings / Birdy 500 Miles / the Proclaimers BACK TO MENU EMAIL | FACEBOOK | TWITTER | YOUTUBE | INSTAGRAM © 2018. The Cairn String Quartet. All Rights Reserved Charts 50, 60, 70, 80s BACK TO MENU A Forrest / The Cure A Hard Days Night / The Beatles A Little Help from My Friends / The Beatles A Little respect / Erasure Africa / Toto Ain't No Mountain High Enough / Marvin Gaye/Diana Ross Albatross / Fleetwood Mac All I Want is You -

Musikindustrie in Zahlen: Jahrbuch 2015

MUSIKINDUSTRIE IN ZAHLEN 2015 UMSATZ Plus 4,6 Prozent: Deutscher Musikmarkt wächst 2015 deutlich STREAMING Plus 106 Prozent: Streaming Subscriptions übertreffen Prognose REPERTOIRE Acht der Top 10-Alben in den Offiziellen Deutschen Charts 2015 deutschprachig EDITORIAL INHALT 2 Editorial 4 Umfrage zur Musiknutzung 6 Ein Blick zurück 8 Umsatz 16 Absatz 20 Musikfirmen 24 Musiknutzung 28 Musikkäufer 34 Musikhandel 38 Repertoire und Charts 52 Jahresrückblick 53 Vorstände und Geschäftsführer 54 Impressum 1 EDITORIAL EDITORIAL Rotation waren und sind seit jeher un- ser Business! Gleichzeitig sind wir aber mit der relativen Langsamkeit des Rechts- rahmens konfrontiert, sei es im natio- nalen Bereich, sei es auf europäischer wenn man noch ein kleines bisschen Ebene, sei es mit Blick auf die zuneh- weiter zurückschaut, verzeichnen wir mend auch global zu besprechenden ZUKUNFT IM HIER UND JETZT sogar schon das dritte Jahr ein positives Rechtsthemen von Urheberrecht bis zu ODER: „DAUERND MORGEN“ Ergebnis. Woran liegt das? Wir haben Datenschutz. Allein der im November – UND EIN GUTES JAHR 2015 nach wie vor eine gesunde Balance aus 2015 wieder neu, diesmal vor dem Bun- So einiges, was wir im vergangenen Jahr physischen und digitalen Nutzungsfor- desverfassungsgericht aufgeschnürte Fall an dieser Stelle noch ziemlich weit ent- men und Musikformaten in Deutsch- „Metall auf Metall“ begleitet uns seit fernt am Horizont gesehen haben, ist land: Das Streaming wächst weiter 1997, seit bald 20 Jahren also. Die Lang- innerhalb der letzten zwölf Monate Teil kräftig, die CD-Umsätze sind moderat samkeit in Bezug auf manche Change- unserer Wirklichkeit geworden. Auto- rückläufig und Vinyl legte auch 2015 in Prozesse ist aber nicht nur den Müh(l)en nome Autos sind keine Konzeptskizze seiner Nische deutlich zweistellig zu. -

Hozier: Take Me to Church Written by Andrew Hozier-Byrne from the Album “Hozier” (2014) 4/4, 125 Bpm

Hozier: Take Me To Church Written by Andrew Hozier-Byrne From the album “Hozier” (2014) 4/4, 125 bpm VERSE 1 Em Am½ Date BPM Strum (0:00) My lover's got humour Em Am½ She's the giggle at a funeral G Am½ Knows everybody's disapproval Em Am½ I should've worshiped her sooner Em Am½ If the heavens ever did speak Em Am½ She's the last true mouthpiece G Am½ Every Sunday's getting more bleak Em Am½ A fresh poison each week D C 'We were born sick,' you heard them say it VERSE 2 Em Am½ (0:27) My Church offers no absolutes Em Am½ She tells me, 'Worship in the bedroom' G Am½ The only heaven I'll be sent to Em Am½ Is when I'm alone with you D C C (HOLD FOR 2) I was born sick, but I love it, command me to be well G C½ G Cm½ G Cm½ G (0:45) A____A___men, A_____men, A___men CHORUS Em Em B7 (0:57) Take me to church, I'll worship like a dog at the shrine of your lies B7 G I'll tell you my sins and you can sharpen your knife Am Em Offer me that deathless death, good God, let me give you my life Em Em B7 Take me to church, I'll worship like a dog at the shrine of your lies B7 G I'll tell you my sins so you can sharpen your knife Am Em Offer me that deathless death, good God, let me give you my life www.rynaylorguitar.com Hozier: Take Me To Church VERSE 3 Em Am½ (1:27) If I'm a pagan of the good times Em Am½ My lover's the sunlight G Am½ To keep the Goddess on my side Em Am½ She demands a sacrifice D C Drain the whole sea, get something shiny Em Am½ (1:42) Something meaty for the main course Em Am½ That's a fine looking high horse G Am½ What you got in the stable? Em Am½ We've a lot of starving faithful D C C That looks tasty, that looks plenty, this is hungry work (2:00) [CHORUS] BRIDGE C G B7 Em (2:30) No Masters or Kings when the Ritual begins C G B7 Em There is no sweeter innocence than our gentle sin C G B7 Em In the madness and the soil of that sad earthly scene C G B7 Em Em/D G/C C Only then I am human, only then I am clean G C½ G Cm½ G Cm½ G (3:06) Oh A____men, A_____men, A___men (3:18) [CHORUS] END ON Em (4:02) 2 www.rynaylorguitar.com . -

The Mix Song List

THE MIX SONG LIST CONTEMPORARY 2010’s CENTURIES/ fall out boy 24K MAGIC/ bruno mars CHAINED TO THE RHYTHM/ katy perry ADDICTED TO A MEMORY/ zedd CHANDELIER/ sia ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME/ coldplay CHEAP THRILLS/ sia & sean paul AFTERGLOW/ ed sheeran CHEERLEADER/ omi AIN’T IT FUN/ paramore CIRCLES/ post malone AIRPLANES/ b.o.b w/haley williams CLASSIC/ mkto ALIVE/ krewella CLOSER/ chainsmokers ALL ABOUT THAT BASS/ meghan trainor CLUB CAN’T HANDLE ME/ flo rida ALL ABOUT THAT BASS/ postmodern jukebox COME GET IT BAE/ pharrell williams ALL I NEED/ awol nation COOLER THAN ME/ mike posner ALL I ASK/ adele COOL KIDS/ echosmith ALL OF ME/ john legend COUNTING STARS/ one republic ALL THE WAY/ timeflies CRAZY/ kat dahlia ALWAYS REMEMBER US THIS WAY/ lady gaga CRUISE REMIX/ florida georgia line & nelly A MILLION DREAMS/ greatest showman DANGEROUS/ guetta & martin AM I WRONG/ nico & vinz DAYLIGHT/ maroon 5 ANIMALS/ maroon 5 DEAR FUTURE HUSBAND/ meghan trainor ANYONE/ justin bieber DELICATE/ taylor swift APPLAUSE/ lady gaga DIAMONDS/ sam smith A THOUSAND YEARS/ christina perri DIE WITH YOU/ beyonce BABY/ justin bieber DIE YOUNG/ kesha BAD BLOOD/ taylor swift DOMINO/ jessie j BAD GUY/ billie eilish DON’T LET ME DOWN/ chainsmokers BANG BANG/ jessie j and ariana grande DON’T START NOW/ dua lipa BEFORE I LET GO/ beyonce DON’T STOP THE PARTY/ pitbull BENEATH YOUR BEAUTIFUL/ labrinth DRINK YOU AWAY/ justin timberlake BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE/ chris brown DRIVE BY/ train BEST DAY OF MY LIFE/ american authors DRIVERS LICENSE/ olivia rodrigo BEST SONG EVER/ one direction -

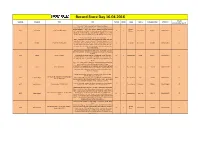

Record Store Day 16.04.2016 AT+CH Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN (Ja/Nein/Über Wen?)

Record Store Day 16.04.2016 AT+CH Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN (ja/nein/über wen?) Picture disc LP with artwork by Drew Millward (Foo Fighters) Broken Thrills is Beach Slang's first European release, compiling their debut EPs, both released in the US in 2014. The LP is released via Big Scary Monsters Big Scary ALIVE Beach Slang Broken Thrills (RSD 2016) LP 1 Independent 6678317 5060366783172 AT (La Dispute, Gnarwolves, Minus The Bear) and coincides with their first tour Monsters outside of the States, including Groezrock festival in Belgium and a run of UK headline dates. For fans of: Jawbreaker, Gaslight Anthem and Cheap Girls. 12'' Clear Vinyl, 4 Remixes of "Get Lost" + One Cover After the new album "Still Waters" recently released, and sustained by the lively "Back For More" and the captivating "2Good4Me", Breakbot is back ALIVE Breakbot Get Lost Remixes (RSD 2016) with a limited edition EP of 4 "Get Lost" remixes and one exclusive cover by 12" 1 Ed Banger Disco / Dance 2156290 5060421562902 AT the band Jamaica. Still with his sidekick Irfane, Breakbot is more than ever determined to make us dance with a new succession of hits each one more exciting than the last. LIMITED DOUBLE 12'' WITH PRINTED INNER SLEEVES: "ACTION" IS THE 1ST SINGLE OF CASSIUS 'S NEW ALBUM (release date 24.06.2016). This EP features 6 TRACKS, ALIVE Cassius Action (RSD 2016) Exclusively for the Record Store Day, the first single "Action" from the 12" 2 Because Music House 2156427 5060421564272 AT upcoming album releases as a double 12'' edition.