Book of the Lost Narrator: Rereading the 1977 Silmarillion As a Unified Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloadable

Chronology of the Silmarillion 1 ____ Chronology of the Silmarillion By clotho123 ___ This was put together as a potentially useful guide rather than a rigid framework and I would not regard anything here as set in stone. Tolkien did quite a bit of work on the legends after drawing up his final chronologies and might very well have changed many of the dates if he’d ever reached the point of publishing The Silmarillion. It was compiled from three of Tolkien’s chronological writings: The Annals of Aman, published in The History of Middle-earth: Morgoth’s Ring, Part Two The Grey Annals, published in The History of Middle-earth: The War of the Jewels, Part One with final section and revisions in Part Three, section I The Tale of Years, published in The History of Middle-earth: The War of the Jewels, Part Three, section V The Beginning of Time These dates are from the Annals of Aman. How precisely you think they should be interpreted is up to the individual. They are all in Valian years, which according to Tolkien’s opening description, were each roughly equivalent to ten Sun years (strictly 9.582 Sun years, if you want to be exact). At other times he had other views on the relationship between elven years and mortal years, but I will not go into those here as he did not have them in mind when compiling the Annals. 1 Valar first enter Arda 1500 Tulkas enters Arda 1900 Valar set up the great Lamps 3400 Melkor begins to make Utumno 3450 Melkor destroys the Lamps 3500 The Two Trees are created (1) The Ages of the Trees These annals also are all in years of the Valar. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

“To Trees All Men Are Orcs”: the Environmental Ethic of J.R.R. Tolkien's “The New Shadow” (Forthcoming in Tolkien Studies)

“To trees all Men are Orcs”: The environmental ethic of J.R.R. Tolkien's “The New Shadow” (forthcoming in Tolkien Studies) Introduction In the last few decades, a number of works have aimed to examine the environmental ethics implicit in the writings of J.R.R. Tolkien (e.g. Brisbois 2005, Curry 1997, Dickerson and Evans 2006, Ekman 2013, Habermann and Kuhn 2011, Jeffers 2014, Resta 1990, Simonson 2015). The great majority of this scholarly attention has focused on the text of the published Lord of the Rings, with some secondary consideration for The Hobbit and The Silmarillion. In doing so, scholars (aside from brief mentions by Birzer 2003 and Flieger 2000) have passed over what may be Tolkien's most explicit statement about environmental ethics in his writings about his legendarium: a debate between the characters Saelon and Borlas in The New Shadow, his abortive attempt to write a sequel to The Lord of the Rings (Tolkien 1996). Saelon and Borlas directly consider the proper relationship of humans to nature, and the limits of our exploitation of it. This paper's purpose is twofold. After introducing recent scholarship on Tolkien as an environmental writer and the text of the Saelon-Borlas debate, I first bring these two bodies of writing together, showing how the debate in The New Shadow reflects and extends the environmental perspective contained in Tolkien's better-known works. Second, I bring the debate into conversation with another significant body of literature, that of normative environmental ethics. I show how the claims made by Saelon and Borlas reflect sophisticated thinking about questions of biocentrism and anthropocentrism, and of the possibility of respectful use of nature, that environmental ethicists have weighed. -

Tolkien Encyclopedia

Tolkien Encyclopedia The Accursed • Oromë • Uldor Algund Adanedhel • A member of the Guar-waith. • Túrin Almarian Adurant • The daughter of Vëantur, husband of • A tributary of Gelion. Meneldur, and mother of Anardil, Ailinel, and Almiel. Aegnor • Elvish son of Finarfin. Almiel • Called: Egnor • A daughter of Meneldur and Almarian. Aelin-uial Alqualondë • The Twilight Meres • The mansions of Olwë in Aman. • Called: The Haven of Swans. Aerandir • A mariner who sailed with Eärendil to Aman Aman. • Home of the Valar. Across the Outer Sea from Arda Aerin • Called: The Land of Aman, the Blessed • A relative of Húrin. The wife of Brodda, an Realm, the Guarded Realm Easterling. The daughter of Indor. Amlach The After-born • The son of Imlach. • Men Amon Ereb The Aftercomers • A hill in Ossiriand where Denethor died • Men during the First Battle of the Wars of Beleriand. Agarwaen • Túrin Amon Ethir • A hill raised by Finrod in front of Aglon Nargothrond. • Himlad • Called: The Spyhill Ailinel Amon Gwareth • A daughter of Meneldur and Almarian, the • A mountain in Tumladen. wife of Orchaldor, and mother of Soronto. Amon Obel Ainairos • A mountain in Brethil. • An Elf of Alqualondë who stirred up the Valar against Melkor. Amon Rûdh • Mîm’s home in the west of Doriath. The Ainu of Evil • Called: Sharbhund, the Bald Hill, Bar-en- • Melkor Danwedh, the House of Ransom, Echad i Sedryn, Camp of the Faithful Alcarinquë and Elemmírë • Stars Amras • Elvish son of Fëanor. Aldarion • Anardil Amrod • Elvish son of Fëanor. Aldaron Tolkien Encyclopedia Anadûnê Anduin the Great • Andor • A river in Arda Anardil Andúnië • The son of Meneldur and Almarian. -

Small Renaissances Engendered in JRR Tolkien's Legendarium

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2017 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Dominic DiCarlo Meo Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meo, Dominic DiCarlo, "'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium" (2017). Senior Honors Theses. 555. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/555 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Abstract After surviving the trenches of World War I when many of his friends did not, Tolkien continued as the rest of the world did: moving, growing, and developing, putting the darkness of war behind. He had children, taught at the collegiate level, wrote, researched. Then another Great War knocked on the global door. His sons marched off, and Britain was again consumed. The "War to End All Wars" was repeating itself and nothing was for certain. In such extended dark times, J. R. R. Tolkien drew on what he knew-language, philology, myth, and human rights-peering back in history to the mythologies and legends of old while igniting small movements in modern thought. Arthurian, Beowulfian, African, and Egyptian myths all formed a bedrock for his Legendarium, and fantasy-fiction as we now know it was rejuvenated.Just like the artists, authors, and thinkers from the Late Medieval period, Tolkien summoned old thoughts to craft new creations that would cement themselves in history forever. -

JRR Tolkien's Genealogies

Tolkien’s Genealogies J.R.R. Tolkien’s Genealogies: The Roots of his ‘Sub creation’ Daniel Timmons As many critics have noted, Tolkien’s books have they liked to have books filled with things that provoked both condemnations and laurels. However, they already knew, set out fair and square with to borrow the author’s view from his “Valedictory no contradictions. Address,” I do not think it is helpful to confront (Tolkien, 1966a, p. 26) simplistic opinions of a given work and then provide Tolkien’s tone is light here, and there is some irony fuel for a “faction fight” (Tolkien, 1983, p. 231). A apparent when he says hobbits like “books filled with role of a scholar is to offer perspectives on the depth things that they already knew;” many who disparage and significance of a text, and minimize a political The Lord of the Rings do it because the work is not agenda or self-aggrandizement. It is much more real to life, as they purport to know it. Still, all the worthwhile to focus on subjects where Tolkien’s details given are contrived to be serious and accomplishments are widely acknowledged. authentic. If we had nothing more to go on, the mere Foremost of these, of course, is the vast and intricate size and appearance of hobbits could work against Middle-earth: Tolkien’s unique “Sub-creation,” attempts to suspend our disbelief. Tolkien’s narrator which is unmatched by any English literary work. plainly states he is relating a ‘history’ - not a fiction. Tolkien’s genealogies not only exhibit the complexity The Lord of the Rings is said to be an account drawn of this “Sub-creation” but in fact serve as one of the from the “Red Book of Westmarch” (Tolkien, 1966a, central grounds - the roots, if you will - of his p.34), a book that was originally a private diary of fictional invention. -

TOLKIEN‟S the SILMARILLION: a REEXAMINATION of PROVIDENCE by David C. Powell a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Dorothy

TOLKIEN‟S THE SILMARILLION: A REEXAMINATION OF PROVIDENCE by David C. Powell A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 2009 Copyright by David C. Powell ii ABSTRACT Author: David C. Powell Title: Tolkien‟s The Silmarillion: A Reexamination of Providence Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Thomas Martin Degree Master of Arts Year 2009 Christian providence in the primary (real) world operates as the model for the spiritual movement of Eru/Illuvatar in Tolkien‟s secondary (imaginative) world. Paralleling the Christian God, Illuvatar maintains a relationship with his creation through a three-fold activity: preservation, concurrence, and government. Preservation affirms Eru‟s sovereignty as Creator, and concurrence guarantees creaturely freedom, while paradoxically, government controls, guides, and determines those wills in Time. The union of these three activities comprises the providential relationship of Illuvatar in Tolkien‟s imaginary world. The following thesis endeavors to carry the argument for providence into The Silmarillion with a declarative and analytical detail that distinguishes Illuvatar‟s providence from other temporal manifestations. Finally, the analysis reveals not only the author‟s authentic orthodox perspective, but Illuvatar‟s role in the imaginative world emerges as a reflection of Tolkien‟s authorial role in the real world. iv TOLKIEN‟S THE SILMARILLION: A REEXAMINATION OF PROVIDENCE ABBREVIATIONS . .vi INTRODUCTION . 1 CHAPTER ONE: PRESERVATION . 7 CHAPTER TWO: CONCURRENCE . 17 CHAPTER THREE: GOVERNMENT . 50 WORKS CITED . 66 NOTES . .71 v ABBREVIATIONS Aspects “Aspects of the Fall in The Silmarillion.” Eric Schweicher. -

Bibliography of Recommended Secondary Sources I. General

Bibliography of recommended secondary sources With thanks to Denise Leathers for the initial version (items in bold are available via links to our blog as .pdf files; listings in Green show local holdings) I. General Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1973 [1949]. (PIC/PC/RWU) Enright, Nancy. “Tolkien’s Females and the Defining of Power.” Renascence 59.2 (2007): 93-108. Flieger, Verlyn. “Fantasy and Reality: J.R.R. Tolkien’s World and the Fairy-Story Essay.” Mythlore 22.3 (1999): 4-13. Le Guin, Ursula K. “The Child and the Shadow,” and “The Staring Eye.” In The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction. NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1979. (RIC, PC, RWU) Northrup, Clyde. “The Qualities of a Tolkienian Fairy-Story.” Modern Fiction Studies 50.4 (2004): 814-837. Shippey. Tom. “Light-elves, Dark-elves and Others: Tolkien’s Elvish Problem.” Tolkien Studies 1.1 (2004): 1-15. Smith, Thomas W. “Tolkien’s Catholic Imagination: Mediation and Tradition.” Religion and Literature 38.2 (2006): 73-100. Tolkien, J.R.R. “On Fairy Stories” (first given as a lecture in 1939, published in 1947, and since brought out in a critical edition edited by Verlyn Flieger and Douglas A. Anderson (2008). (ILL) ---------------. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Humphrey Carpenter. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981. (RIC, PC). II. The Legendarium Beare, Rhona. “A Mythology for England.” In Allan Turner, ed., The Silmarillion: Thirty Years On. Zürich: Walking Tree Publishers, 2007 (ILL) Fisher, Jason. “Tolkien’s Fortunate Fall and The Third Theme of Ilúvatar.” In Jonathan B. -

Worldbuilding in Tolkien's Middle-Earth and Beyond

KULT_online. Review Journal for the Study of Culture journals.ub.uni-giessen.de/kult-online (ISSN 1868-2855) Issue 61 (May 2020) Worldbuilding in Tolkien’s Middle-earth and Beyond Dennis Friedrichsen Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen [email protected] Abstract: The field of worldbuilding in literary studies is experiencing a revitalization and it is therefore unsurprising that interest in Tolkien’s Middle-earth is renewed. Many aspects of Tolkien’s world have been analyzed and discussed, but it remains a relevant topic for both specific questions concerning Tolkien’s world and general questions concerning worldbuilding in literature. Sub-creating Arda , edited by Dimitra Fimi and Thomas Honegger, makes a valuable contribution that expands on both theoretical areas, applies theories of worldbuilding to Middle-earth, and draws interesting parallels to other fictional worlds. Because the field of worldbuilding is incredibly rich, Sub-creating Arda is not exhaustive, but nevertheless makes significant contributions to contemporary academic problematizations of the field and will undoubtedly inspire new arguments and new approaches within the field of worldbuilding. How to cite: Friedrichsen, Dennis: “Worldbuilding in Tolkien’s Middle-earth and Beyond [Review of: Fimi, Dimitra and Thomas Honegger (eds.): Sub-creating Arda. World-building in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Work, Its Precursors, and Its Legacies. Zurich: Walking Tree Publishers, 2019.]“. In: KULT_online 61 (202o). DOI: https://doi.org/10.22029/ko.2020.1034 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International KULT_online. Review Journal for the Study of Culture 61 / 2020 journals.ub.uni-giessen.de/kult-online Worldbuilding in Tolkien’s Middle-earth and Beyond Dennis Friedrichsen Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen Fimi, Dimitra and Thomas Honegger (eds.). -

Clashing Perspectives of World Order in JRR Tolkien's Middle-Earth

ABSTRACT Fate, Providence, and Free Will: Clashing Perspectives of World Order in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth Helen Theresa Lasseter Mentor: Ralph C. Wood, Ph.D. Through the medium of a fictional world, Tolkien returns his modern audience to the ancient yet extremely relevant conflict between fate, providence, and the person’s freedom before them. Tolkien’s expression of a providential world order to Middle-earth incorporates the Northern Germanic cultures’ literary depiction of a fated world, while also reflecting the Anglo-Saxon poets’ insight that a single concept, wyrd, could signify both fate and providence. This dissertation asserts that Tolkien, while acknowledging as correct the Northern Germanic conception of humanity’s final powerlessness before the greater strength of wyrd as fate, uses the person’s ultimate weakness before wyrd as the means for the vindication of providence. Tolkien’s unique presentation of world order pays tribute to the pagan view of fate while transforming it into a Catholic understanding of providence. The first section of the dissertation shows how the conflict between fate and providence in The Silmarillion results from the elvish narrator’s perspective on temporal events. Chapter One examines the friction between fate and free will within The Silmarillion and within Tolkien’s Northern sources, specifically the Norse Eddas, the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf, and the Finnish The Kalevala. Chapter Two shows that Tolkien, following Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, presents Middle-earth’s providential order as including fated elements but still allowing for human freedom. The second section shows how The Lord of the Rings reflects but resolves the conflict in The Silmarillion between fate, providence, and free will. -

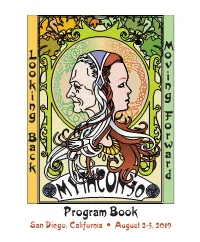

Mythcon 50 Program Book

M L o o v o i k n i g n g F o r B w a a c r k d Program Book San Diego, California • August 2-5, 2019 Mythcon 50: Moving Forward, Looking Back Guests of Honor Verlyn Flieger, Tolkien Scholar Tim Powers, Fantasy Author Conference Theme To give its far-flung membership a chance to meet, and to present papers orally with audience response, The Mythopoeic Society has been holding conferences since its early days. These began with a one-day Narnia Conference in 1969, and the first annual Mythopoeic Conference was held at the Claremont Colleges (near Los Angeles) in September, 1970. This year’s conference is the third in a series of golden anniversaries for the Society, celebrating our 50th Mythcon. Mythcon 50 Committee Lynn Maudlin – Chair Janet Brennan Croft – Papers Coordinator David Bratman – Programming Sue Dawe – Art Show Lisa Deutsch Harrigan – Treasurer Eleanor Farrell – Publications J’nae Spano – Dealers’ Room Marion VanLoo – Registration & Masquerade Josiah Riojas – Parking Runner & assistant to the Chair Venue Mythcon 50 will be at San Diego State University, with programming in the LEED Double Platinum Certified Conrad Prebys Aztec Student Union, and onsite housing in the South Campus Plaza, South Tower. Mythcon logo by Sue Dawe © 2019 Thanks to Carl Hostetter for the photo of Verlyn Flieger, and to bg Callahan, Paula DiSante, Sylvia Hunnewell, Lynn Maudlin, and many other members of the Mythopoeic Society for photos from past conferences. Printed by Windward Graphics, Phoenix, AZ 3 Verlyn Flieger Scholar Guest of Honor by David Bratman Verlyn Flieger and I became seriously acquainted when we sat across from each other at the ban- quet of the Tolkien Centenary Conference in 1992. -

Lioi, Anthony. "The Great Music: Restoration As Counter-Apocalypse in the Tolkien Legendarium." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "The Great Music: Restoration as Counter-Apocalypse in the Tolkien Legendarium." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 123–144. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 12:12 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 The Great Music: Restoration as Counter-Apocalypse in the Tolkien Legendarium In which I assert that J. R. R. Tolkien’s legendarium begins with an enchanted sky, which provides the narrative framework for a restoration ecology based on human alliance with other creatures. This alliance protects local and planetary environments from being treated like garbage. Tolkien’s restorative framework begins in the Silmarillion with “The Music of the Ainur,” a cosmogony that details the creation of the universe by Powers of the One figured as singers and players in a great music that becomes the cosmos. This is neither an organic model of the world as body nor a technical model of the world as machine, but the world as performance and enchantment, coming- into-being as an aesthetic phenomenon. What the hobbits call “magic” in the Lord of the Rings is enchantment, understood as participation in the music of continuous creation. In his essay “On Fairy-Stories,” Tolkien theorized literary enchantment as the creation of a “Secondary World” of art that others could inhabit.