Independent and Combined Effects of Age, Body Mass Index And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Provider-Based Evaluation (Probe) 2014 Preliminary Report

The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE) 2014 Preliminary Report I. Background of ProBE 2014 The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE), continuation of the formerly known Malaysia Government Portals and Websites Assessment (MGPWA), has been concluded for the assessment year of 2014. As mandated by the Government of Malaysia via the Flagship Coordination Committee (FCC) Meeting chaired by the Secretary General of Malaysia, MDeC hereby announces the result of ProBE 2014. Effective Date and Implementation The assessment year for ProBE 2014 has commenced on the 1 st of July 2014 following the announcement of the criteria and its methodology to all agencies. A total of 1086 Government websites from twenty four Ministries and thirteen states were identified for assessment. Methodology In line with the continuous and heightened effort from the Government to enhance delivery of services to the citizens, significant advancements were introduced to the criteria and methodology of assessment for ProBE 2014 exercise. The year 2014 spearheaded the introduction and implementation of self-assessment methodology where all agencies were required to assess their own websites based on the prescribed ProBE criteria. The key features of the methodology are as follows: ● Agencies are required to conduct assessment of their respective websites throughout the year; ● Parents agencies played a vital role in monitoring as well as approving their agencies to be able to conduct the self-assessment; ● During the self-assessment process, each agency is required to record -

Community Vulnerability on Dengue and Its Association with Climate Variability in Malaysia: a Public Health Approach

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2010, Vol. 10 (2): 25-34 ORIGINAL ARTICLE COMMUNITY VULNERABILITY ON DENGUE AND ITS ASSOCIATION WITH CLIMATE VARIABILITY IN MALAYSIA: A PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH Mazrura S1, Rozita Hod2, Hidayatulfathi O1, Zainudin MA3, , Mohamad Naim MR1, Nadia Atiqah MN1, Rafeah MN1, Er AC 5, Norela S6, Nurul Ashikin Z1, Joy JP 4 1 Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, National University of Malaysia, Jalan Raja Muda Abdul Aziz, 50300, Kuala Lumpur 2 Department of Community Health, UKM Medical Centre 3 Seremban District Health Office 4 LESTARI, National University of Malaysia, Bangi 5 Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, National University of Malaysia, Bangi 6 Faculty of Sciences and Technology, National University of Malaysia, Bangi ABSTRACT Dengue is one of the main vector-borne diseases affecting tropical countries and spreading to other countries at the global scenario without cease. The impact of climate variability on vector-borne diseases is well documented. The increasing morbidity, mortality and health costs of dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) are escalating at an alarming rate. Numerous efforts have been taken by the ministry of health and local authorities to prevent and control dengue. However dengue is still one of the main public health threats in Malaysia. This study was carried out from October 2009 by a research group on climate change and vector-borne diseases. The objective of this research project is to assess the community vulnerability to climate variability effect on dengue, and to promote COMBI as the community responses in controlling dengue. This project also aims to identify the community adaptive measures for the control of dengue. -

(CPRC), Disease Control Division, the State Health Departments and Rapid Assessment Team (RAT) Representative of the District Health Offices

‘Annex 26’ Contact Details of the National Crisis Preparedness & Response Centre (CPRC), Disease Control Division, the State Health Departments and Rapid Assessment Team (RAT) Representative of the District Health Offices National Crisis Preparedness and Response Centre (CPRC) Disease Control Division Ministry of Health Malaysia Level 6, Block E10, Complex E 62590 WP Putrajaya Fax No.: 03-8881 0400 / 0500 Telephone No. (Office Hours): 03-8881 0300 Telephone No. (After Office Hours): 013-6699 700 E-mail: [email protected] (Cc: [email protected] and [email protected]) NO. STATE 1. PERLIS The State CDC Officer Perlis State Health Department Lot 217, Mukim Utan Aji Jalan Raja Syed Alwi 01000 Kangar Perlis Telephone: +604-9773 346 Fax: +604-977 3345 E-mail: [email protected] RAT Representative of the Kangar District Health Office: Dr. Zulhizzam bin Haji Abdullah (Mobile: +6019-4441 070) 2. KEDAH The State CDC Officer Kedah State Health Department Simpang Kuala Jalan Kuala Kedah 05400 Alor Setar Kedah Telephone: +604-7741 170 Fax: +604-7742 381 E-mail: [email protected] RAT Representative of the Kota Setar District Health Office: Dr. Aishah bt. Jusoh (Mobile: +6013-4160 213) RAT Representative of the Kuala Muda District Health Office: Dr. Suziana bt. Redzuan (Mobile: +6012-4108 545) RAT Representative of the Kubang Pasu District Health Office: Dr. Azlina bt. Azlan (Mobile: +6013-5238 603) RAT Representative of the Kulim District Health Office: Dr. Sharifah Hildah Shahab (Mobile: +6019-4517 969) 71 RAT Representative of the Yan District Health Office: Dr. Syed Mustaffa Al-Junid bin Syed Harun (Mobile: +6017-6920881) RAT Representative of the Sik District Health Office: Dr. -

Towards Balanced and Sustained Economic Growth

VOL. 3 ISSUE 1, 2021 07 HIGH IMPACT PROJECTS OF STATE STRUCTURE PLAN OF NEGERI SEMBILAN2045– TOWARDS BALANCED AND SUSTAINED ECONOMIC GROWTH *Abdul Azeez Kadar Hamsa, Mansor Ibrahim, Irina Safitri Zen, Mirza Sulwani, Nurul Iman Ishak & Muhammad Irham Zakir Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Kulliyyah of Architecture and EnvironmentalDesign, International Islamic University Malaysia ABSTRACT METHODOLOGY Figure 1 shows the process in the preparation of State Structure Plan This article is a review of Negeri Sembilan Draft State Structure Plan 2045. State structure plan sets the framework for the spatial planning and development to be translated in more detail in the next stage of development planning which is local plan. The review encompasses the goal, policies, thrusts and proposals to lead the development of Negeri Sembilan for the next 25 years. This review also highlights 9 high-impact projects proposed to be developed in Negeri Sembilan at the state level by 2045 through 30 policies and 107 strategies. Keywords: Structure plan, spatial planning, local plan, development thrust, Literature Review Negeri Sembilan * Corresponding author: [email protected] Preparation of Inception Report INTRODUCTION Sectors covered: State Structure Plan is a written statement that sets the framework for the spatial - Land Use - Public facilities planning and development of the state as stated in Section 8 of Town and - Socio economy - Infrastructure and utilities Country Planning Act (Act 172). The preparation of Negeri Sembilan Structure - Population - Traffic and transportation Plan 2045 is necessary to be reviewed due to massive economic development - Housing and settlement - Urban design change and the introduction of new policies at the national level over the past 20 - Commercial - Environmental heritage years. -

A Feasibility Study of Multiple Micronutrient Supplement for Home Fortification of Foods Among Orang Asli Children in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia

Mal J Nutr 25(1): 69-77, 2019 A feasibility study of multiple micronutrient supplement for home fortification of foods among Orang Asli children in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia Nur Dayana Shaari, Zalilah Mohd Shariff*, Gan Wan Ying & Loh Su Peng Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia ABSTRACT Introduction: The prevalence of child undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies are higher in the Orang Asli (OA) than the general Malaysian population. The World Health Organization recommends the use of multiple micronutrient supplement (MMS) that is a blend of micronutrients in powder form that can be sprinkled onto foods for home fortification to prevent undernutrition among children. This pilot study aimed to assess the feasibility of using MMS among OA children. Methods: A total of 25 OA children (14 boys and 11 girls) aged 6-31 months (mean±SD = 15.7±7.2 months) in Negeri Sembilan were given three sachets of MMS weekly for 5 weeks. Caregivers were instructed to add MMS to three types of food from the same food group per week varying with a different food group weekly. Written instruction for using MMS in simple language was given prior to the supplementation. Caregivers were interviewed for information on socio-demographics, compliance, acceptance, preference and adverse effect of MMS. Results: A high level of compliance was observed (85%). All caregivers reported that the instructions for use were easy to read. No noticeable changes to the foods mixed with MMS were observed and no adverse effects were reported. Conclusion: This study demonstrated feasibility of the use of MMS for future trials among OA children. -

Spatial Pattern Distribution of Dengue Fever in Sub-Urban Area Using Gis Tools

Serangga 21(2): 127-148 ISSN 1394-5130 © 2016, Centre for Insects Systematic, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia SPATIAL PATTERN DISTRIBUTION OF DENGUE FEVER IN SUB-URBAN AREA USING GIS TOOLS Masnita Md Yusof1,2, Nazri Che Dom1, Ariza Zainuddin2 1Faculty of Health Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), UiTM Kampus Puncak Alam, 42300 Bandar Puncak Alam, Selangor, Malaysia 2Pejabat Kesihatan Daerah Jempol, 72120 Bandar Seri Jempol, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Dengue fever (DF) is one of the major public health problems in Malaysia. The number of cases recorded is always fluctuating. The aim of the study is to identify the high-risk area for the occurrence of dengue disease. Spatial-temporal model was used by measuring three characteristics which are frequency, duration and intensity to define the severity and magnitude of outbreak transmission. This study examined a total of 386 registered dengue fever cases, geo-coded by address in Jempol district between January 2011 and December 2015. Even though case notification figures are subjected to bias, this information is available in the health services. It may lead to crucial conclusion, recommendations, and hypotheses. Public health officials can utilize the temporal risk indices to describe dengue relatively than relying on the traditional case incident figures. 128 Serangga Keywords: spatial pattern distribution, dengue fever, sub-urban, GIS tools, Jempol, Malaysia. ABSTRAK Demam denggi (DD) merupakan masalah kesihatan awam yang utama di Malaysia. Kes demam denggi yang dicatatkan sentiasa berubah-ubah. Pada tahun 1901, kes demam denggi pertama kali dilaporkan di Pulau Pinang, dan selepas itu ianya menjadi endemik di kebanyakan kawasan bandar. -

Epidemiological Characteristics of COVID-19 in Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia

Scientific Foundation SPIROSKI, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020 Nov 16; 8(T1):471-475. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.5461 eISSN: 1857-9655 Category: T1 - Thematic Issue “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)” Section: Public Health Epidemiology Epidemiological Characteristics of COVID-19 in Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia Mohd ‘Ammar Ihsan Ahmad Zamzuri1,2, Farah Edura Ibrahim1, Muhammad Alimin Mat Reffien1, Mohd Fathulzhafran Mohamed Hanan1, Muhamad Hazizi Muhamad Dasani2, Noor Khalili Mohd Ali2, Hasanain Faisal Ghazi3, Mohd Rohaizat Hassan1* 1Department of Community Health, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2Seremban District Health Office, Negeri Sembilan State Health Department, Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia; 3College of Nursing, Al-Bayan University, Baghdad, Iraq Abstract Edited by: Mirko Spiroski BACKGROUND: Coronavirus disease (COVID)-19 has become a global pandemic with an increasing burden on Citation: Zamzuri MAIA, Ibrahim FE, Reffien MAM, Hanan MFM, Dasani MHM, Ali NKM, Ghazi HF, healthcare. Early recognition of the trend and pattern of the chain of transmission is necessary to slow down the Hassan MR. Epidemiological Characteristics of COVID-19 spread. in Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2020 Nov 16; 8(T1):471-475. AIM: Therefore, the study aimed to describe the epidemiology of COVID-19 at a local setting. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.5461 Keywords: Epidemiology; Coronavirus disease-19; METHODS: A retrospective cross-sectional study was done to all COVID-19 cases registered in Seremban Health Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; Malaysia; Seremban District. Statistical analysis, using Chi-square test, was employed to compare the sociodemographic characteristic of *Correspondence: Dr. -

Elder Mistreatment in a Community Dwelling Population: the Malaysian Elder Mistreatment Project (MAESTRO) Cohort Study Protocol

Downloaded from http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on December 20, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com Open Access Protocol Elder mistreatment in a community dwelling population: the Malaysian Elder Mistreatment Project (MAESTRO) cohort study protocol Wan Yuen Choo,1 Noran Naqiah Hairi,1 Rajini Sooryanarayana,1 Raudah Mohd Yunus,1 Farizah Mohd Hairi,1 Norliana Ismail,1 Shathanapriya Kandiben,1 Zainudin Mohd Ali,2 Sharifah Nor Ahmad,2 Inayah Abdul Razak,2 Sajaratulnisah Othman,3 Maw Pin Tan,4 Fadzilah Hanum Mohd Mydin,3 Devi Peramalah,1 Patricia Brownell,5 Awang Bulgiba1 To cite: Choo WY, Hairi NN, ABSTRACT et al Strengths and limitations of this study Sooryanarayana R, . Introduction: Despite being now recognised as a Elder mistreatment in a global health concern, there is still an inadequate ▪ community dwelling This study is among the first few cohort studies amount of research into elder mistreatment, especially population: the Malaysian investigating into elder mistreatment in the South Elder Mistreatment Project in low and middle-income regions. The purpose of this East Asian region. (MAESTRO) cohort study paper is to report on the design and methodology of a ▪ It has a prospective study design with a long protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6: population-based cohort study on elder mistreatment period of follow-up, with emphasis not only on e011057. doi:10.1136/ among the older Malaysian population. The study aims epidemiological characteristics of elder mistreat- bmjopen-2016-011057 at gathering data and evidence to estimate the ment but also on determinants at different levels prevalence and incidence of elder mistreatment, of framework and measuring consequences of ▸ Prepublication history for identify its individual, familial and social determinants, abuse. -

Public Health Research

Dengue Epidemic Threshold PUBLIC HEALTH RESEARCH Determining Method for Dengue Epidemic Threshold in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia Lokman Rejali,2 Shamsul Azhar Shah,1 *Norzaher Ismail,1 Syafiq Taib,1 Siti Nor Mat,1 Mohd Rohaizat Hassan1 and Nazarudin Safian1 1Department of Community Health, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Jalan Yaacob Latif, 56000, Cheras , Kuala Lumpur ,Malaysia. 2Vector Unit, Jabatan Kesihatan Negeri Sembilan, Jalan Rasah, Bukit Rasah, 70300 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. *For reprint and all correspondence: Norzaher Ismail, Department of Community Health, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Jalan Yaacob Latif, 56000, Cheras , Kuala Lumpur ,Malaysia Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Received 23 July 2019 Accepted 15 June 2020 Introduction Dengue fever is an arthropod-borne viral disease that has become endemic in most tropical countries. In 2014, Malaysia reported 108 698 cases of dengue fever with 215 deaths which increased tremendously compared to 49 335 cases with 112 deaths in 2008 and 30 110 cases with 69 deaths in 2009. This study aimed to identify the best method in determining dengue outbreak threshold for Negeri Sembilan as it can help to send uniform messages to inform the general public and make the outbreak analysis comparable within and between countries. Methods Using retrospective Negeri Sembilan country dataset from 1st epid week of 2011 till the 52nd epid week of 2016. The data were split into two periods: 1) a 3-year historic period (2011–2013), used to calibrate and parameterise the model, and a 1-year evaluation period (2014); 2) a 2-year historic period (2014–2016), used to calibrate and parameterise the model, and a 1-year evaluation period (2016), used to test the model. -

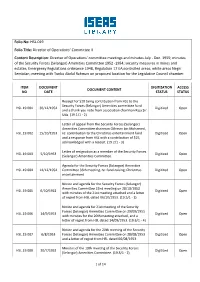

Folio No: HSL.019 Folio Title: Director of Operations' Committee II Content

Folio No: HSL.019 Folio Title: Director of Operations’ Committee II Content Description: Director of Operations' committee meetings and minutes July - Dec. 1955; minutes of the Security Forces (Selangor) Amenities Committee 1952 -1954; security measures in mines and estates; Emergency Regulations ordinance 1948, Regulation 17 EA;controlled areas; white areas Negri Sembilan; meeting with Tunku Abdul Rahman on proposed location for the Legislative Council chamber. ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS Receipt for $20 being contribution from HSL to the Security Forces (Selangor) Amenities committee fund HSL.19.001 30/12/1954 Digitized Open and a thank you note from association chairman Raja Sir Uda. (19.1/1 - 2) Letter of appeal from the Security Forces (Selangor) Amenities Committee chairman Othman bin Mohamed, HSL.19.002 15/10/1953 re: contribution to the Christmas entertainment fund Digitized Open and a response from HSL with a contribution of $25, acknowledged with a receipt. (19.2/1 - 3) Letter of resignation as a member of the Security Forces HSL.19.003 5/10/1953 Digitized Open (Selangor) Amenities Committee. Agenda for the Security Forces (Selangor) Amenities HSL.19.004 14/12/1954 Committee 36th meeting, re: fund-raising; Christmas Digitized Open entertainment. Notice and agenda for the Security Forces (Selangor) Amenities Committee 22nd meeting on 28/10/1953 HSL.19.005 6/10/1953 Digitized Open with minutes of the 21st meeting attached and a letter of regret from HSL dated 06/10/1953. (19.5/1 - 3) Notice and agenda for 21st meeting of the Security Forces (Selangor) Amenities Committee on 29/09/1955 HSL.19.006 14/9/1953 Digitized Open with minutes for the 20th meeting attached, and a letter of regret from HSL dated 14/09/1953. -

Preliminary Study of Sg Serai Hot Spring, Hulu Langat, Malaysia

Water Conservation and (WC )1(1) (2017) 11-14 Management M Contents List available at Water Conservation and Volkson Press (WC ) Journal Homepage: https://www.watconman.org/Management M Preliminary Study of Sg Serai Hot Spring, Hulu Langat, Malaysia Alea Atiqah Bt Mahzan, Anis Syafawanie Bt Ramli, Anis Syafiqah Bt Mohd Abduh, Izulalif B. Izhar, Mohd Zarif B. Mohd Yusof Indirakumar, Amgad Abdelazim Mohamed Salih, Anas Syafiq B. Ahmad Jahri, Ong Qing Wei Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article history: The study was conducted to do preliminary review of geology & water quality at Sg Serai hot spring, Hulu Langat, Selangor, Malaysia. Langat River basin can be divided into 3 distinct zones. The first can be referred to as the Received 12 August 2016 mountainous zone of the northeast corner of Hulu Langat district. The second zone is the hilly area Accepted 12 December 2016 characterised by gentle slopes spreading widely from north to the east in the middle part of Langat basin. Available online 20 January 2017 The third zone is a relatively flat alluvial plane located in the southwest of Langat Basin. Water samples, SSP2 and SSW2 are polluted, with an anomalously high reading of fluoride. Fluorosis has been described as an Keywords: endemic disease of tropical climates, but this is not entirely the case. Waters with high fluoride concentrations occur in large and extensive geographical belts associated with a) sediments of marine origin in mountainous areas, b) Preliminary report, geology, water quality, Langat basin, flouride volcanic rocks and c) granitic and gneissic rocks; resulting the high concentration of fluoride in water samples. -

Managing the Public During the Nipah Virus Outbreak in Negeri Sembilan

Buletin Kesihatan Masyarakat Isu Khas 2000 69 MANAGING THE PUBLIC DURING THE NIPAH VIRUS OUTBREAK IN NEGERI SEMBILAN Ramlee R..* INTRODUCTION The first Nipah virus outbreak was detected in Negeri Sembilan on 4th January 1999. It all started in Kampung Dato' Wong Seng Chow, Sikamat, in the district of Seremban. The outbreak was then identified as Japanese Encephalitis (JE). The machinery for control of JE was mobilised as soon as the outbreak in Perak was reported. That was done as early as 20th October 1998 with the collection of baseline data of all pig farms in the state. The state was put on alert and health education materials were produced and distributed. Among the communication challenges faced in controlling the outbreak were issues related to the handling of the pig farmers, workers, general public, the mass media, the encephalitis cases and their family members, non govermental organisations (NGO), health-care workers and other personels involved. THE FARMERS AND WORKERS The pig farms in Bukit Pelanduk area, coded BP I for Bukit Pelanduk I (Bukit Pelanduk II (BP II), coded for Sepang), Port Dickson, were different that those found in Perak and Seremban District. The farms in Perak were located in fruit orchards and the farmers and their workers did not stay in the farms. The farms in Seremban were well organised, fenced with living quarters for the workers within the farms with the farmers or owners staying elsewhere. The farms have proper drainage system for waste water from the pigsty to oxidation ponds before being discharged into the river Unlike the farms in Perak and Seremban, the farms in BP I were scattered within oil palm estates, with no proper fences and no proper drainage system.