Managing the Public During the Nipah Virus Outbreak in Negeri Sembilan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Btsisi', Blandas, and Malays

BARBARA S. NOWAK Massey University SINGAN KN÷N MUNTIL Btsisi’, Blandas, and Malays Ethnicity and Identity in the Malay Peninsula Based on Btsisi’ Folklore and Ethnohistory Abstract This article examines Btsisi’ myths, stories, and ethnohistory in order to gain an under- standing of Btsisi’ perceptions of their place in Malaysia. Three major themes run through the Btsisi’ myths and stories presented in this paper. The first theme is that Austronesian-speaking peoples have historically harassed Btsisi’, stealing their land, enslaving their children, and killing their people. The second theme is that Btsisi’ are different from their Malay neighbors, who are Muslim; and, following from the above two themes is the third theme that Btsisi’ reject the Malay’s Islamic ideal of fulfilment in pilgrimage, and hence reject their assimilation into Malay culture and identity. In addition to these three themes there are two critical issues the myths and stories point out; that Btsisi’ and other Orang Asli were original inhabitants of the Peninsula, and Btsisi’ and Blandas share a common origin and history. Keywords: Btsisi’—ethnic identity—origin myths—slaving—Orang Asli—Peninsular Malaysia Asian Folklore Studies, Volume 63, 2004: 303–323 MA’ BTSISI’, a South Aslian speaking people, reside along the man- grove coasts of the Kelang and Kuala Langat Districts of Selangor, HWest Malaysia.1* Numbering approximately two thousand (RASHID 1995, 9), Btsisi’ are unique among Aslian peoples for their coastal location and for their geographic separation from other Austroasiatic Mon- Khmer speakers. Btsisi’, like other Aslian peoples have encountered histori- cally aggressive and sometimes deadly hostility from Austronesian-speaking peoples. -

For Sale - Bandar Spring Hill Height Lukut Port Dickson , Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan

iProperty.com Malaysia Sdn Bhd Level 35, The Gardens South Tower, Mid Valley City, Lingkaran Syed Putra, 59200 Kuala Lumpur Tel: +603 6419 5166 | Fax: +603 6419 5167 For Sale - Bandar Spring Hill Height Lukut Port Dickson , Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan Reference No: 101040084 Tenure: Freehold Address: 281 Jalan Spring Hill 11/16 , Occupancy: Vacant Lukut Port Dickson , Negeri Furnishing: Partly furnished Sembilan Darul Khusus, Bandar Spring Hill Height Lukut Port Unit Type: Corner lot Dickson , 71010, Negeri Land Title: Residential Sembilan Property Title Type: Individual State: Negeri Sembilan Posted Date: 03/01/2021 Property Type: Bungalow Facilities: Parking, 24-hours security Asking Price: RM 750,000 Property Features: Kitchen cabinet,Air Built-up Size: 2,800 Square Feet conditioner,Garage,Garden Name: Aaron Leong Built-up Dimension: 56 x 50 Company: REAPFIELD PROPERTIES (HQ) SDN. BHD. Built-up Price: RM 267.86 per Square Feet Email: [email protected] Land Area Size: 12,260 Square Feet Land Area 105 x 120 Dimension: Land Area Price: RM 61.17 per Square Feet No. of Bedrooms: 4 No. of Bathrooms: 3 FOR SALE: 2 Storey Bungalow Bandar Springhill Port Dickson PD ___________________________________________ * Nearby : Lukut Port Dickson Bandar Sri Sendayan Seremban *Build Up :2800 Sq.ft * Tenure : Freehold And Non-Bumi Lot * Land Size: 12260Sq.Ft * Bedrooms : 4 * Bathrooms: 3 ___________________________________________ Unit Price: Price: RM 750,000 / 750K Negotiable SMS/Whatsapp/call: 019-3806687 REN (42070) Email Address:[email protected] Agency Name : Reapfield Properties (HQ) Sdn Bhd ___________________________________________ Highlight: * Well Maintained [Move .... [More] View More Details On iProperty.com iProperty.com Malaysia Sdn Bhd Level 35, The Gardens South Tower, Mid Valley City, Lingkaran Syed Putra, 59200 Kuala Lumpur Tel: +603 6419 5166 | Fax: +603 6419 5167 For Sale - Bandar Spring Hill Height Lukut Port Dickson , Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan . -

Negeri Ppd Kod Sekolah Nama Sekolah Alamat Bandar Poskod Telefon Fax Negeri Sembilan Ppd Jempol/Jelebu Nea0025 Smk Dato' Undang

SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH NEGERI SEMBILAN KOD NEGERI PPD NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT BANDAR POSKOD TELEFON FAX SEKOLAH PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA0025 SMK DATO' UNDANG MUSA AL-HAJ KM 2, JALAN PERTANG, KUALA KLAWANG JELEBU 71600 066136225 066138161 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD SMK DATO' UNDANG SYED ALI AL-JUFRI, NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA0026 BT 4 1/2 PERADONG SIMPANG GELAMI KUALA KLAWANG 71600 066136895 066138318 JEMPOL/JELEBU SIMPANG GELAMI PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6001 SMK BAHAU KM 3, JALAN ROMPIN BAHAU 72100 064541232 064542549 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6002 SMK (FELDA) PASOH 2 FELDA PASOH 2 SIMPANG PERTANG 72300 064961185 064962400 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6003 SMK SERI PERPATIH PUSAT BANDAR PALONG 4,5 & 6, GEMAS 73430 064666362 064665711 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6005 SMK (FELDA) PALONG DUA FELDA PALONG 2 GEMAS 73450 064631314 064631173 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6006 SMK (FELDA) LUI BARAT BANDAR SERI JEMPOL 72120 064676300 064676296 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6007 SMK (FELDA) PALONG 7 FELDA PALONG TUJUH GEMAS 73470 064645464 064645588 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6008 SMK (FELDA) BANDAR BARU SERTING BANDAR SERI JEMPOL 72120 064581849 064583115 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6009 SMK SERTING HILIR KOMPLEKS FELDA SERTING HILIR 4 72120 064684504 064683165 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6010 SMK PALONG SEBELAS (FELDA) FELDA PALONG SEBELAS GEMAS 73430 064669751 064669751 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6011 SMK SERI JEMPOL -

The Provider-Based Evaluation (Probe) 2014 Preliminary Report

The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE) 2014 Preliminary Report I. Background of ProBE 2014 The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE), continuation of the formerly known Malaysia Government Portals and Websites Assessment (MGPWA), has been concluded for the assessment year of 2014. As mandated by the Government of Malaysia via the Flagship Coordination Committee (FCC) Meeting chaired by the Secretary General of Malaysia, MDeC hereby announces the result of ProBE 2014. Effective Date and Implementation The assessment year for ProBE 2014 has commenced on the 1 st of July 2014 following the announcement of the criteria and its methodology to all agencies. A total of 1086 Government websites from twenty four Ministries and thirteen states were identified for assessment. Methodology In line with the continuous and heightened effort from the Government to enhance delivery of services to the citizens, significant advancements were introduced to the criteria and methodology of assessment for ProBE 2014 exercise. The year 2014 spearheaded the introduction and implementation of self-assessment methodology where all agencies were required to assess their own websites based on the prescribed ProBE criteria. The key features of the methodology are as follows: ● Agencies are required to conduct assessment of their respective websites throughout the year; ● Parents agencies played a vital role in monitoring as well as approving their agencies to be able to conduct the self-assessment; ● During the self-assessment process, each agency is required to record -

MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN NEGERI SEMBILAN D/A Kompleks Jabatan Kebudayaan Dan Kesenian N

MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN NEGERI SEMBILAN d/a Kompleks Jabatan Kebudayaan dan Kesenian N. Sembilan, Taman Budaya Negeri, Jalan Sungai Ujong,70200 Seremban, N.Sembilan Pn. Noridah Nawi MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH TAMPIN D/A Majlis Daerah Tampin, 73009 Tampin, Negeri Pahang, En. Shah Kamruddin b. Hj. Hashim MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH JELEBU D/A Pejabat Daerah dan Tanah Jelebu, 71600 Kuala Klawang, Negeri Sembilan En. Md. Said b. Ahmad MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH PORT DICKSON D/A Majlis Perbandaran Port Dickson, 71009 Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan En. Mohd Hashim b. Md. Taib MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH KUALA PILAH D/A Pejabat Daerah dan Tanah Kuala Pilah, 72000 Kuala Pilah, Negeri Sembilan En. Mohd Nizar b. Abdullah MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH SEREMBAN D/A Pejabat Daerah dan Tanah Seremban, Kompleks Pentadbiran Daerah Persiaran S2 A2, 70300 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan Tn. Hj. Dahlan Hj. Abdullah MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAERAH REMBAU D/A Pejabat Daerah dan tanah Rembau, Kompleks Pentadbiran Daerah Rembau, 71309 rembau, Negeri Sembilan En. Nazri b. Yunus MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH JEMPOL D/A Pejabat daerah dan Tanah jempol, 72120 Bandar Baru Serting, jempol, Negeri Sembilan En. Mazdar b. Abd. Aziz PERSADA STUDIO C-13A, Tingkat 14, Street View, Batu 7, Marina World, Teluk Kemang, 71009 Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan Pn. Sabariah bt. Maarof CITRA BUDAYA, KELAB MELAYU NEGERI SEMBILAN 114,12 ½ Jalan Seremban Kuala Pilah 70400 Seremban Batu 2 ¼, Jalan Kuala Pilah, 70400 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan. En. Mohd Effendi b. Othman D’SETRA JELEBU No.59, Kampung Mengkan, 71600 Kuala Klawang, Negeri Sembilan En. Kamarul b. -

Community Vulnerability on Dengue and Its Association with Climate Variability in Malaysia: a Public Health Approach

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2010, Vol. 10 (2): 25-34 ORIGINAL ARTICLE COMMUNITY VULNERABILITY ON DENGUE AND ITS ASSOCIATION WITH CLIMATE VARIABILITY IN MALAYSIA: A PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH Mazrura S1, Rozita Hod2, Hidayatulfathi O1, Zainudin MA3, , Mohamad Naim MR1, Nadia Atiqah MN1, Rafeah MN1, Er AC 5, Norela S6, Nurul Ashikin Z1, Joy JP 4 1 Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, National University of Malaysia, Jalan Raja Muda Abdul Aziz, 50300, Kuala Lumpur 2 Department of Community Health, UKM Medical Centre 3 Seremban District Health Office 4 LESTARI, National University of Malaysia, Bangi 5 Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, National University of Malaysia, Bangi 6 Faculty of Sciences and Technology, National University of Malaysia, Bangi ABSTRACT Dengue is one of the main vector-borne diseases affecting tropical countries and spreading to other countries at the global scenario without cease. The impact of climate variability on vector-borne diseases is well documented. The increasing morbidity, mortality and health costs of dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) are escalating at an alarming rate. Numerous efforts have been taken by the ministry of health and local authorities to prevent and control dengue. However dengue is still one of the main public health threats in Malaysia. This study was carried out from October 2009 by a research group on climate change and vector-borne diseases. The objective of this research project is to assess the community vulnerability to climate variability effect on dengue, and to promote COMBI as the community responses in controlling dengue. This project also aims to identify the community adaptive measures for the control of dengue. -

Negeri Sembilan

SPECIAL STUDY MSC Malaysia 2.0 State ICT Blueprint : Negeri Sembilan Roger Ling Devtar Singh Hailey Chan Victor Lim Liew Siew Choon 03, Level 13, Menara HLA 3, Jalan Kia Peng 50450 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia P.60.3.2163.3715 Malaysia Lumpur, Kuala 50450 Peng Kia Jalan 3, HLA Menara 13, 03, Level - Suite 13 Suite Filing Information: December 2010, IDC #, Volume: 1 Special Reports: Special Study TABLE OF CONTENTS P Introduction & Background 1 Point of Departure: State ICT Blueprint – Negeri Sembilan 3 Overview ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Economic Landscape ............................................................................................................................... 5 Negeri Sembilan Key Contributing Sectors ....................................................................................... 5 Manufacturing ............................................................................................................................. 5 Services...................................................................................................................................... 6 Agriculture .................................................................................................................................. 8 Construction ............................................................................................................................... 9 Mining ........................................................................................................................................ -

Sendayan Techvalley

BANDAR SRI SENDAYAN a first-class township where home is for you and your loved ones. Located within the Greater Klang Valley Conurbation in Seremban on 5,233 acres of freehold land, Bandar Sri Sendayan is planned and designed with one thing in mind; comfortable living & business friendly. A premier integrated development made complete with ample facilities and amenities, BANDAR SRI SENDAYAN is without a doubt a sanctuary of tranquil tropical living, wholesome values and most importantly, a sense of community. Families find it an oasis of fulfillment; businesses see it as a world of promising opportunities. Being Part of the Greater Klang Valley Conurbation, along the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia, where it is merely a 20-minute drive to THE MASTER PLAN OF BANDAR SRI SENDAYAN Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) and a 35-minute journey to Kuala Lumpur (KL). Located within very close proximity to existing and progressing town centres such as Cyberjaya and Putrajaya, the North-South and the proposed Senawang-KLIA Expressways offer from smoother and faster alternatives to major destinations. KUALA LUMPUR / PUTRAJAYA New Seremban Toll ( Approved New Alignment ) DESTINATION 1 KUALA LUMPUR 70 KM MALACCA 75 KM KLIA 22 KM GEORGETOWN, PENANG 369 KM PUTRAJAYA / CYBERJAYA 60 KM ISKANDAR M’SIA, JOHOR 261 KM PORT KLANG 95 KM WOODLANDS, SINGAPORE 270 KM PORT DICKSON 20 KM 21km 22km 23km SEREMBAN North South Hig 2 from NILAI KPJ LANG VALLEY Specialist Hospital hway UALA LUMPUR Seremban Toll CONURBATION & BANDAR SRI SENDAYAN Taman S2 Heights -

(CPRC), Disease Control Division, the State Health Departments and Rapid Assessment Team (RAT) Representative of the District Health Offices

‘Annex 26’ Contact Details of the National Crisis Preparedness & Response Centre (CPRC), Disease Control Division, the State Health Departments and Rapid Assessment Team (RAT) Representative of the District Health Offices National Crisis Preparedness and Response Centre (CPRC) Disease Control Division Ministry of Health Malaysia Level 6, Block E10, Complex E 62590 WP Putrajaya Fax No.: 03-8881 0400 / 0500 Telephone No. (Office Hours): 03-8881 0300 Telephone No. (After Office Hours): 013-6699 700 E-mail: [email protected] (Cc: [email protected] and [email protected]) NO. STATE 1. PERLIS The State CDC Officer Perlis State Health Department Lot 217, Mukim Utan Aji Jalan Raja Syed Alwi 01000 Kangar Perlis Telephone: +604-9773 346 Fax: +604-977 3345 E-mail: [email protected] RAT Representative of the Kangar District Health Office: Dr. Zulhizzam bin Haji Abdullah (Mobile: +6019-4441 070) 2. KEDAH The State CDC Officer Kedah State Health Department Simpang Kuala Jalan Kuala Kedah 05400 Alor Setar Kedah Telephone: +604-7741 170 Fax: +604-7742 381 E-mail: [email protected] RAT Representative of the Kota Setar District Health Office: Dr. Aishah bt. Jusoh (Mobile: +6013-4160 213) RAT Representative of the Kuala Muda District Health Office: Dr. Suziana bt. Redzuan (Mobile: +6012-4108 545) RAT Representative of the Kubang Pasu District Health Office: Dr. Azlina bt. Azlan (Mobile: +6013-5238 603) RAT Representative of the Kulim District Health Office: Dr. Sharifah Hildah Shahab (Mobile: +6019-4517 969) 71 RAT Representative of the Yan District Health Office: Dr. Syed Mustaffa Al-Junid bin Syed Harun (Mobile: +6017-6920881) RAT Representative of the Sik District Health Office: Dr. -

(Emeer 2008) State: Negeri Sembilan

LIST OF INSTALLATIONS AFFECTED UNDER EFFICIENT MANAGEMENT OF ELECTRICAL ENERGY REGULATIONS 2008 (EMEER 2008) STATE: NEGERI SEMBILAN NO. INSTALLATION NAME ADDRESS PT 11634, JALAN TECHVALLEY 3B/1, SENDAYAN TECHVALLEY, 71900 1 AKASHI KIKAI INDUSTRY (M) SDN BHD BANDAR SRI SENDAYAN, NEGERI SEMBILAN SENAWANG LAMINATING LOT 55, PSN BUNGA TANJUNG 1, KAW PERUSAHAAN, SENAWANG, 70450, 2 TECHNOLOGIES SDN BHD NEGERI SEMBILAN LOT MO 72, PERSIARAN BUNGA TANJUNG 1, SENAWANG INDUSTRIAL 3 NIPPON WIPER BLADE (M) SDN BHD PARK, 70400 SEREMBAN, NEGERI SEMBILAN KAMPUS, JLN SEREMBAN TIGA 1, SEREMBAN 3, MAMBAU, 70300, NEGERI 4 UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI MARA (UITM) SEMBILAN PK AGRO INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTS (M) PT 98, SENAWANG INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, 70400 SEREMBAN, NEGERI 5 SDN BHD - SENAWANG FOOD DIVISION SEMBILAN LOT 3850-3855 CHEMBONG PHASE II, INDUSTRIAL ESTATE CHEMBONG, 6 G.B. INDUSTRIES SDN BHD 71300 REMBAU, NEGERI SEMBILAN STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION CENTRE (STRACOMM), UNIVERSITI SAINS 7 UNIVERSITI SAINS ISLAM MALAYSIA ISLAM MALAYSIA, BANDAR BARU NILAI, 71800, NILAI, NEGERI SEMBILAN 12TH MILE, JALAN PANTAI, PASIR PANJANG, 71250 PORT DICKSON, 8 LEXIS HIBISCUS PORT DICKSON NEGERI SEMBILAN NO. 277 JALAN HARUAN 1, OAKLAND INDUSTRIAL PARK, SEREMBAN 2, 9 COMBI-PACK SDN BHD 70300 SEREMBAN, NEGERI SEMBILAN LOT 3430, KAWASAN PERINDUSTRIAN R O WATER SDN BHD - MANTIN 10 RINGAN BT.8 MANTIN,71700 MANTIN BRANCH NEGERI SEMBILAN LOT 62&63, LORONG SENAWANG 3/2, SENAWANG INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, 11 UG GLOBAL RESOURCES SDN BHD 70450 SEREMBAN, NEGERI SEMBILAN LOT 120 & 121, JALAN SENAWANG 3, SENAWANG INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, 12 CAREPLUS (M) SDN.BHD. 70450 SEREMBAN, NEGERI SEMBILAN GREAT PLATFORM SDN BHD - SIMPANG LOT 7056, KAWASAN PERINDUSTRIAN, SIMPANG PERTANG, 72300 13 PERTANG JELEBU, NEGERI SEMBILAN INTERPRINT DECOR (MALAYSIA) SDN LOT 121, JALAN PERMATA 2, ARAB-MALAYSIAN INDUSTRIAL PARK, 71800 14 BHD NILAI NEGERI SEMBILAN 15 HIGHWAY QUARRY SDN BHD 872/2, JLN LABU-NILAI BT 12, 71800, NILAI, NEGERI SEMBILAN 406, KAW . -

Towards Balanced and Sustained Economic Growth

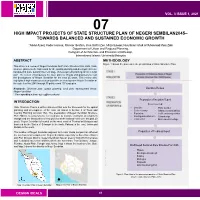

VOL. 3 ISSUE 1, 2021 07 HIGH IMPACT PROJECTS OF STATE STRUCTURE PLAN OF NEGERI SEMBILAN2045– TOWARDS BALANCED AND SUSTAINED ECONOMIC GROWTH *Abdul Azeez Kadar Hamsa, Mansor Ibrahim, Irina Safitri Zen, Mirza Sulwani, Nurul Iman Ishak & Muhammad Irham Zakir Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Kulliyyah of Architecture and EnvironmentalDesign, International Islamic University Malaysia ABSTRACT METHODOLOGY Figure 1 shows the process in the preparation of State Structure Plan This article is a review of Negeri Sembilan Draft State Structure Plan 2045. State structure plan sets the framework for the spatial planning and development to be translated in more detail in the next stage of development planning which is local plan. The review encompasses the goal, policies, thrusts and proposals to lead the development of Negeri Sembilan for the next 25 years. This review also highlights 9 high-impact projects proposed to be developed in Negeri Sembilan at the state level by 2045 through 30 policies and 107 strategies. Keywords: Structure plan, spatial planning, local plan, development thrust, Literature Review Negeri Sembilan * Corresponding author: [email protected] Preparation of Inception Report INTRODUCTION Sectors covered: State Structure Plan is a written statement that sets the framework for the spatial - Land Use - Public facilities planning and development of the state as stated in Section 8 of Town and - Socio economy - Infrastructure and utilities Country Planning Act (Act 172). The preparation of Negeri Sembilan Structure - Population - Traffic and transportation Plan 2045 is necessary to be reviewed due to massive economic development - Housing and settlement - Urban design change and the introduction of new policies at the national level over the past 20 - Commercial - Environmental heritage years. -

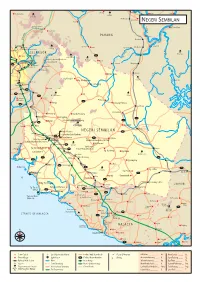

Negeri Sembilan•State

Lancang Mentakab Ulu Yam Baharu 391 Kg. Ira Cenur 1772 Bt. Woh G. Ulu Kali Ptn. Belengu Temerluh Kg. Tualang Kg. Kertau Karak NEGERI SEMBILAN Genting Highlands g n a Kg. Tebing Tinggi Kg. Bt. Tinggi h a Janda Baik P Bukit Tinggi . g k S a b m P AHANG o Kg. Jelam G . g Mengkarak S ng . Kla Batu Caves Sg Kg. Mengkarak 1493 Sg. Gepoi Gepoi Ptn. Menteri Gombak G. Nuang Kg. Cerang Gombak Orang Asli Centre a r Batu Caves e ng B . 472 ia SELANGOR r g e S Bertangga ga t T Teriang Kuala Ampang an 9 . Setapak . L 1462 g g G. Besar Hantu S S 781 Sungai Chongkak Recreational Forest KUALA LUMPUR Bt. Idung Mancis Jalan Duta Sungai Gabai Waterfalls Mengkuang 111 FEDERAL TERRITORY Kg. Jawi-Jawi Ampang National Zoo Dusun Tua Hulu Langat g Kemayan tin ra Be Be Durian Tipus . g g S S 315 Kg. Kongkoi Senurang S. Besi Kg. Ulu Gelimau Bera Lake Cheras Mines Kg. Temelang Serdang Wonderland Kachau UPM 209 Kajang 210 Kajang 809 Titi 645 1 Bt. Ulu Beranang Palong Tasik Dampar Cyberjaya Semenyih Putrajaya Pertang 86 Beroga Simpang Pertang 212 Bangi Bangi Ayer Hitam Kg. Serting Beranang Kg. Ulu Klawang Batang Benar Lenggeng 10 Forest Reserve Lenggeng 9 Mantin g Nilai 215 n o 1193 l a G. Telapa Buruk P Nilai Batu Kikir . Salak g Bahau S • State Mosque NEGERI SEMBILAN 13 Labu Tiroi • Seremban Lake Gardens Seremban 218 • State Library 51 K. Pilah S State Museum g. SEREMBAN Ulu Bendul Recreational Park M Cultural Handicraft Complex uar Sepang 825 Sri Menanti Port Dickson 219 G.