The Lighter Side of My Official Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 Halsbury's Laws of England (3) RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE

Page 1 Halsbury's Laws of England (3) RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE CROWN AND THE JUDICIARY 133. The monarch as the source of justice. The constitutional status of the judiciary is underpinned by its origins in the royal prerogative and its legal relationship with the Crown, dating from the medieval period when the prerogatives were exercised by the monarch personally. By virtue of the prerogative the monarch is the source and fountain of justice, and all jurisdiction is derived from her1. Hence, in legal contemplation, the Sovereign's Majesty is deemed always to be present in court2 and, by the terms of the coronation oath and by the maxims of the common law, as also by the ancient charters and statutes confirming the liberties of the subject, the monarch is bound to cause law and justice in mercy to be administered in all judgments3. This is, however, now a purely impersonal conception, for the monarch cannot personally execute any office relating to the administration of justice4 nor effect an arrest5. 1 Bac Abr, Prerogative, D1: see COURTS AND TRIBUNALS VOL 24 (2010) PARA 609. 2 1 Bl Com (14th Edn) 269. 3 As to the duty to cause law and justice to be executed see PARA 36 head (2). 4 2 Co Inst 187; 4 Co Inst 71; Prohibitions del Roy (1607) 12 Co Rep 63. James I is said to have endeavoured to revive the ancient practice of sitting in court, but was informed by the judges that he could not deliver an opinion: Prohibitions del Roy (1607) 12 Co Rep 63; see 3 Stephen's Commentaries (4th Edn) 357n. -

The FAO Journal VOLUME XIII, NUMBER 1 February 2010

The FAO Journal VOLUME XIII, NUMBER 1 February 2010 Defeating Islamists at the Ballot Reflections on the fall of The Wall The AKP’s Hamas Policy Transformation of Turk Foreign Policy and the Turk view of the West 4th Generation War on Terror The ―New Great Game‖ for the Modern Operator Mentorship - Leaving a Legacy The US-Indonesia Military Relationship Dynamic Cooperation for Common Security Interests Service Proponent Updates and Book Reviews DISCLAIMER: Association’s International Affairs Journal (a none-profit publication The Foreign Area Officer Association’s Journal for US Regional and International Affairs professionals) is printed by the Foreign Area Officer Association, Mount Vernon, The FAO Journal VA. The views expressed within are those of the various authors, not of the Depart- Politico-Military Affairs - Intelligence - Security Cooperation ment of Defense, the Armed services or any DoD agency, and are intended to advance the profession through thought, dialog and Volume XIII, Edition Number 1 academic discussion. The contents do not reflect a DoD position and are not intended Published February 2010 to supersede official government sources. ISSN 1551-8094 Use of articles or advertisements consti- tutes neither affirmation nor endorsement by FAOA or DoD. PURPOSE: To publish a journal for dis- seminating professional knowledge and Inside This Issue: furnishing information that promotes under- standing between U.S. regional and interna- tional affairs specialists around the world and improve their effectiveness in advising Defeating Islamists at the Ballot Pg 4 decision-makers. It is intended to forge a By: Khairi Abaza and Dr. Soner Cagaptay closer bond between the active, reserve, and retired FAO communities. -

Secret Societies and the Easter Rising

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2016 The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising Sierra M. Harlan Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Harlan, Sierra M., "The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising" (2016). Senior Theses. 49. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF A SECRET: SECRET SOCIETIES AND THE EASTER RISING A senior thesis submitted to the History Faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History by Sierra Harlan San Rafael, California May 2016 Harlan ii © 2016 Sierra Harlan All Rights Reserved. Harlan iii Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the amazing support and at times prodding of my family and friends. I specifically would like to thank my father, without him it would not have been possible for me to attend this school or accomplish this paper. He is an amazing man and an entire page could be written about the ways he has helped me, not only this year but my entire life. As a historian I am indebted to a number of librarians and researchers, first and foremost is Michael Pujals, who helped me expedite many problems and was consistently reachable to answer my questions. -

Thk London Gazette, May 1$ 1874. 2575

THK LONDON GAZETTE, MAY 1$ 1874. 2575, *e vicarage "or vicarages, in his or their diocese or Siis consent, in. writing, to the union of the • said' «* dioceses, being either in the same parish or con- benefices: into one benefice, with cure of souls for- " tiguous to each other; and-of which the aggregate ecclesiastical purposes; that six weeks and upwards1 " population shall not exceed one thousand five trefore certifying such inquiry and consent to yom? •" hundred persons, and the aggregate yearly value Majesty in Council we caused copies in writing ofj " shall not exceed five hundred pounds, may, with the aforesaid representation of the said Lord Bishop " advantage to the interests of religion, be united to be affixed on the principal outer door of the' 4t into one benefice, the said Archbishop of the parish church of each of the said benefices, with " Province shall inquire into the circumstances of notice, to any person or persons interested that hey •"• the case ; and if on such enquiry it shall appear she, or they might, within such six weeks, show- *' to him that such union may be usefully made, cause, in writing, under his, her, or their hand or " and will not be of inconvenient extent, and that j lands to us, the said Archbishop, against such " the patron or patrons of the said benefices, union, and no such cause has been shown; the- " sinecure rectory or rectoriesj vicarage or vicar- representation of the said Lord Bishop of Worces- •" ages respectively, is or are consenting thereto, ter, our inquiry into the circumstances -

The Man Who Enriched – and Robbed – the Tories

Parliamentary History,Vol. 40, pt. 2 (2021), pp. 378–390 The Man Who Enriched – and Robbed – the Tories ALISTAIR LEXDEN House of Lords Horace Farquhar, financier, courtier and politician, was a man without a moral compass. He combined ruthlessness and dishonesty with great charm. As a Liberal Unionist MP in the 1890s, his chief aim was to get a peerage, for which he paid handsomely. He exploited everyone who came his way to increase his wealth and boost his social position, gaining an earldom from Lloyd George, to whose notorious personal political fund he diverted substantial amounts from the Conservative Party, of which he was treasurer from 1911 to 1923, the first holder of that post. The Tories’ money went into his own pocket as well. During these years, he also held senior positions at court, retaining under George V the trust of the royal family which he had won under Edward VII.By the time of his death in 1923,however,his wealth had disappeared,and he was found to be bankrupt. He was a man of many secrets. They have been probed and explored, drawing on such material relating to his scandalous career as has so far come to light. Keywords: Conservative Party; financial corruption; homosexuality; Liberal Unionist Party; monarchy; royal family; sale of honours 1 Horace Brand Farquhar (1844–1923), pronounced Farkwer, 1st and last Earl Farquhar, of St Marylebone,was one of the greatest rogues of his time,a man capable of almost any misdeed or sin short of murder (and it is hard to feel completely confident that he would have drawn thelineeventhere).1 He had three great loves: money, titles and royalty. -

Rewriting Empire: the South African War, the English Popular Press, and Edwardian Imperial Reform

Rewriting Empire: The South African War, The English Popular Press, and Edwardian Imperial Reform Lauren Young Marshall Charlottesville, Virginia B.A. Longwood University, 2004 M.A. Virginia Commonwealth University, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Department of History University of Virginia August, 2017 ________________________________ Dr. Stephen Schuker ________________________________ Dr. Erik Linstrum ________________________________ Dr. William Hitchcock ________________________________ Dr. Bruce Williams Copyright © 2017 Lauren Y Marshall Table of Contents ABSTRACT i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS v INTRODUCTION 1 Historiographical Survey 12 CHAPTER ONE 33 The Press, The Newspapers, and The Correspondents The Pre-War Imperial Context 33 The Rise of The Popular Press 48 The Newspapers, The Correspondents, and Their 52 Motivations CHAPTER TWO 79 The Siege of Mafeking, Army Blunders, and Post-War Military Reform Early Mistakes 79 The Sieges: Mafeking and Its Aftermath 108 The Khaki Election of 1900 152 Post-War Military Reforms 159 CHAPTER THREE 198 Domestic Anti-War Activity, Pro-Boers, and Post-War Social Reform Anti-War Organizations and Demonstrations 198 The Concentration Camps, The Backlash, and Censorship 211 Post-War Social Reforms 227 CHAPTER FOUR 245 The Treaty of Vereeniging, The Fallout, Chamberlain, and Post-War Economic Reform The War’s Conclusion, Treaty Negotiations, and Reactions 245 Post-War Economic Reforms 255 South Africa as a Microcosm of Federation and The 283 Shifting Boer Myth CONCLUSION 290 The War’s Changing Legacy and The Power of the Press BIBLIOGRAPHY 302 i Abstract This dissertation explores the ways in which English newspaper correspondents during the South African War utilized their commentaries and dispatches from the front to expose British imperial weaknesses. -

EXAMINER Issue 4.Pdf

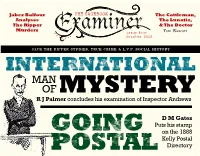

Jabez Balfour THE CASEBOOK The Cattleman, Analyses The Lunatic, The Ripper & The Doctor Murders Tom Wescott issue four October 2010 JACK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY INTERNatIONAL MAN OF MYSTERY R J Palmer concludes his examination of Inspector Andrews D M Gates Puts his stamp GOING on the 1888 Kelly Postal POStal Directory THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 4 October 2010 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of issue four signed articles, essays, letters, reviews October 2010 and other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, may be repro- CONTENTS: duced, stored in a retrieval system, The Lull Before the Storm pg 3 On The Case transmitted or otherwise circulated in any form or by any means, including Subscription Information pg 5 News From Ripper World pg 120 digital, electronic, printed, mechani- On The Case Extra Behind the Scenes in America cal, photocopying, recording or any Feature Stories pg 121 R. J. Palmer pg 6 other, without the express written per- Plotting the 1888 Kelly Directory On The Case Puzzling mission of Casebook.org. The unau- D. M. Gates pg 52 Conundrums Logic Puzzle pg 128 thorized reproduction or circulation of Jabez Balfour and The Ripper Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour this publication or any part thereof, Murders pg 65 Canterbury to Hampton whether for monetary gain or not, is & Herne Bay, Kent pg 130 strictly prohibited and may constitute The Cattleman, The Lunatic, and copyright infringement as defined in The Doctor CSI: Whitechapel Tom Wescott pg 84 Catherine Eddowes pg 138 domestic laws and international agree- From the Casebook Archives ments and give rise to civil liability and Undercover Investigations criminal prosecution. -

Cato Street Brochure

CATO STREET AND THE REVOLUTIONARY TRADITION IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND 12th-13th September 2017 University of Sheffield 1 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Keynote Speakers 4 Conference Schedule 5 Abstracts 9 The Committee 15 2 Five men were executed at Newgate on 1 May 1820 for their part in an attempt to assassinate the British Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, and his cabinet of ministers. The plotters envisaged that they would lead an insurrection across London in the aftermath of their ‘tyrannicide’. The plot is usually referred to as the ‘Cato Street Conspiracy’ after the street in London in which the revolutionaries were arrested. The conspiracy has received surprisingly little scholarly attention, and there has been a tendency among those who have examined Cato Street to dismiss it as an isolated, forlorn, foolhardy and – ultimately – unimportant event. The violent intent of the conspirators sits uncomfortably with notions of what it was (and is) to be English or British. It even sits beyond the pale of ‘mainstream’ radical history in Britain, which tends to be framed in terms of evolution rather than revolution. Even within a revolutionary framework, Cato Street can be discussed as the fantasy of isolated adventurists who had no contact with, or influence upon, ‘the masses’. This conference will examine the Cato Street Conspiracy through a number of different lenses. These perspectives will shed new light on the ‘plot’ itself, its contemporary significance, and its importance (or otherwise) in the longer history of radicalism and revolutionary movements. The Organising Committee of Cato Street 3 Keynote Speakers Sophia A. McClennen is Professor of International Affairs and Comparative Literature at Penn State University, founding director of the Center for Global Studies, and Associate Director of the School of International Affairs. -

Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives Revised Edition - 2005

Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives Revised Edition - 2005 Peter Daerden Maurits Wynants Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren Contents Foreword 7 List of abbrevations 10 P A R T O N E : H E N R Y M O R T O N S T A N L E Y 11 JOURNALS AND NOTEBOOKS 11 1. Early travels, 1867-70 11 2. The Search for Livingstone, 1871-2 12 3. The Anglo-American Expedition, 1874-7 13 3.1. Journals and Diaries 13 3.2. Surveying Notebooks 14 3.3. Copy-books 15 4. The Congo Free State, 1878-85 16 4.1. Journals 16 4.2. Letter-books 17 5. The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, 1886-90 19 5.1. Autograph journals 19 5.2. Letter book 20 5.3. Journals of Stanley’s Officers 21 6. Miscellaneous and Later Journals 22 CORRESPONDENCE 26 1. Relatives 26 1.1. Family 26 1.2. Schoolmates 27 1.3. “Claimants” 28 1 1.4. American acquaintances 29 2. Personal letters 30 2.1. Annie Ward 30 2.2. Virginia Ambella 30 2.3. Katie Roberts 30 2.4. Alice Pike 30 2.5. Dorothy Tennant 30 2.6. Relatives of Dorothy Tennant 49 2.6.1. Gertrude Tennant 49 2.6.2. Charles Coombe Tennant 50 2.6.3. Myers family 50 2.6.4. Other 52 3. Lewis Hulse Noe and William Harlow Cook 52 3.1. Lewis Hulse Noe 52 3.2. William Harlow Cook 52 4. David Livingstone and his family 53 4.1. David Livingstone 53 4.2. -

Victoria Rf,Gine

ANNO DECIMO TERTIO & DECIMO QUARTO VICTORIA RF,GINE. C A P. XCVIII. An Act to amend the Law relating to the holding of Benefices in Plurality. [14th August 1850.] WHEREAS an Act was passed in the Session of Parliament held in the First and Second Years of the Reign of Her present Majesty, intituled An Act to abridge the holding 1 & 2 Vict. c. 106. of Benefices in Plurality, and to make better Provision for the Residence of the Clergy ; and it is by the said Act provided, that no Spiritual Person shall hold together any Two Benefices, if, at 'the Time of his Admission, Institution, or being licensed to the Second Benefice, the Value of the Two Benefices jointly shall exceed the yearly Value of One thousand Pounds, and that the said Benefices shall be within the Distance of Ten Statute Miles the one from the ,other, and that the Population of the said Benefices shall not exceed a certain Amount, as provided by the said Act : And whereas it is desirable further to restrain Spiritual Persons from holding Benefices in Plurality : Be it therefore enacted by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the Authority of the same, That, notwithstanding any Pro- SpiritualPer- sons not to vision in the said recited Act contained, it shall not be lawful, after hold Bene- the passing of this Act, for, any. Spiritual Person to take and hold fices in Plu- rality except together any Two Benefices, except in the Case of Two Benefices the under cer- Churches of which are within Three Miles of one another by the tain Circum- stan ces. -

Zjkcilitants of the 1860'S: the Philadelphia Fenians

zJkCilitants of the 1860's: The Philadelphia Fenians HE history of any secret organization presents a particularly difficult field of inquiry. One of the legacies of secret societies Tis a mass of contradictions and pitfalls for historians. Oaths of secrecy, subterfuge, aliases, code words and wildly exaggerated perceptions conspire against the historian. They add another vexing dimension to the ordinary difficulty of tracing and evaluating docu- mentary sources.1 The Fenian Brotherhood, an international revo- lutionary organization active in Ireland, England, and the United States a century ago, is a case in point. Founded in Dublin in 1858, the organization underwent many vicissitudes. Harried by British police and agents, split by factionalism, buffeted by failures, reverses, and defections, the Fenians created a vivid and romantic Irish nationalist legend. Part of their notoriety derived from spectacular exploits that received sensational publicity, and part derived from the intrepid character of some of the leaders. Modern historians credit the Fenians with the preservation of Irish national identity and idealism during one of the darkest periods of Irish national life.2 Although some general studies of the Fenians have been written, there are few studies of local branches of the Brotherhood. Just how such a group operating in several countries functioned amid prob- lems of hostile surveillance, difficulties of communication, and 1 One student of Irish secret societies, who wrote a history of the "Invincibles," a terrorist group of the i88o's, found the evidence "riddled with doubt and untruth, vagueness and confusion." Tom Corfe, The Phoenix Park Murders (London, 1968), 135. 2 T. -

I1 the PUBLIC LIFE of FRANCIS BACON 0 the Majority of Readers, the Name Francis Bacon T Suggests Immediately One of the Most Versatile Gen- Iuses of All Time

I1 THE PUBLIC LIFE OF FRANCIS BACON 0 the majority of readers, the name Francis Bacon T suggests immediately one of the most versatile gen- iuses of all time. So voluminous and so diversified was the output of his mind in the fields of philosophy, science, and literature, that it is easy to overlook the fact that the man had also a busy career in the alien field of politics, one that possibly was hardly in keeping with the nobility of his other work. Could we but have a true picture of Bacon’s entire career, it would, like the life and even the art of his day, reveal strong contrasts of light and of shadow. The phi- losopher seems hardly the same being as the courtier and politician. A picture of such irreconcilable contrasts is always difficult to evaluate permanently and fairly. Some see only the bright portions while others are more strongly affected by the shadows. So it is with the picture of Bacon. Spedding, his greatest biographer, has sought to gloss over many of his defects; and others, carried away by conspicu- ous political failures, have adopted the un-Baconian attitude of refusing to believe that much good could originate with this political manipulator of the seventeenth century. On the other hand, Pope sought in vain to epitomize fairly the many-sided Bacon as “the wisest, brightest, and meanest of mankind”; and Macaulay, in his melodramatic essay, de- scribed him as a monster, part angel and part snake. End- less controversy has raged over this picture of conflicting tendencies, and so it will always be, for Bacon’s life is an 23 24 Lectures on Francis Bacon enigma.