The Campaigner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

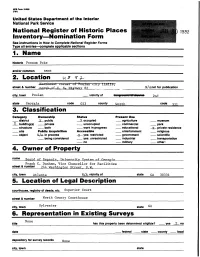

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places 1982 Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_____________' 1. Name_________________ historic Possum Poke and/or common same 2. Location •Noruhuabt CULIUJI ul Poulaii1 street & number -S«- -Hihwa 82 city, town Poulan __ vicinity of uuiiymuuiuiiulUitliiut 2nd state Georgia code 013 county Worth code 32L 3. Classification Cat*Bgory Ownership Status Present Use district X public _ X. occupied agriculture museum X building(s) private unoccuoied commercial park structure both work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Ac<:essible entertainment religious object N/A in process _^ - yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation _no military other; 4. Owner off Property name Board of Regents. University System nf f Frank C. Dunham, Vice Chancellor for Facilities street & number 244 Washington Street. S.W._________ city, town Atlanta N/A vicinity of state GA 30334 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Superior Court street & number Worth County Courthouse city, town Sylvester state GA. 6. Representation in Existing Surveys None title has this property been determined eligible? yes no date federal state county local depository for survey records None city, town state Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated _X— unaltered X original site x good ruins altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Possum Poke is an early 20th Century hunting camp that consists of two dwelling houses on a dirt lane with various outbuildings between them. -

To Chippewa Gentalk Jan 2011-Jan 2016.Xlsx

A B C D E F G CHIPPEWA GENTALK EDITOR'S INDEX: Index of Articles, Authors, Names Mentioned January 2011- January 2016 compiled by K. M. Hendricks, February 2016 1 Chippewa County Genealogical Society 2 ARTICLE DATE of ISSUE PAGE LOCALE Author NAMES 3 ARTICLE CCGS Notes: New Board, Gordon, Reed, 2011-01 11-1 3 Kathleen Steve Gordon, Jan Reed, Kathleen M. HendriCks, Storey, Krupa M. HendriCks, Carol Storey, John Krupa HendriCks 4 Editor's Notes: Farewell to Gail Pratt, 2011-01 11-1 3,14 Sault Ste. Kathleen Gail Pratt, Editor of Chippewa GenTalk, Ladies of Trout Lake Marie M. Marjorie Cooper HendriCks 5 From the President's Pen: Steve Gordon 2011-01 11-1 3,14 Steve researCh, family history, genealogy 6 Gordon Weddings: BurChill-Christie 1908-08- 11-1 4 Rosedale Adeline Christie, Morrison, Wilfred BurChill, 7 06 Nurle, Edwards, Miller, Rosedale Weddings: White-McDonald 1901-11- 11-1 4 Sault Ste. William White, Mary A. McDonald, Easterday 07 Marie 8 Weddings: Bennie-Ganley 1898-09- 11-1 4 Bay Mills Dr. R. Bennie, Julia Ganley, Connolly, Kist, 17 PearCe, Pringle, Bay Mills, Collingwood, Ontario 9 Obituaries: Margaret Perault 1918-01- 11-1 5 Sault Ste. Margaret Cadreau Perault, Joe Raymond, 19 Marie Joseph Cadreau, Martell, Mrs. Charlotte 10 Reynolds, Algonquin, Garden River Dafter Pioneer Breathes Last: RiChard 1918-07- 11-1 5 Dafter RiChard Welsh, Follis, Harper, Cairns, Hembroff, 11 Welsh 15 Wells, Dafter pioneer, Red Cross PolitiCs 100 Years Ago: Chase Osborn 1910-09- 11-1 6 Chippewa Chase S. Osborn, RepubliCan Primary 12 Gets RepubliCan Nomination 07 County A B C D E F G PolitiCs 100 Years Ago: Chase Osborn 1910-11- 11-1 6 Chippewa Chase S. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

Historical Society of Michigan Michigan History Calendar

Historical Society of Michigan Michigan History Calendar Day Year Events 1 APR 1840 The Morris Canal and Banking Company defaulted on payments on Michigan's internal improvement bonds. Michigan's fiscal reputation was ruined when it refused to honor bonds that had been sold, but for which the state had not received payment. 1 APR 1889 The Moiles brothers of De Tour avoided foreclosure of their sawmill by loading all the machinery on 2 barges and taking it to Canada. 1 APR 1901 The last known mastodon to live in Michigan died at the John Ball Zoological Park in Grand Rapids. 1 APR 1906 The state’s first yellow-pages directory was issued by the Michigan State Telephone Company in Detroit. 1 APR 1963 Voters approved Michigan’s fourth state constitution. It replaced the 1908 constitution, changing the terms of the governor and state senators to 4 years. 1 APR 1976 Conrail, a government corporation taking over bankrupt Eastern railroads, began operations in Michigan. The state offered subsidies to private lines operating some former Penn Central and Ann Arbor Railroad lines. 2 APR 1881 Grand Opening of J.L. Hudson’s men and boy’s clothing store in the Detroit Opera House. At start of the Great Depression Hudson’s with its 25 story building was the largest in Michigan and the third largest department store in the country. 2 APR 1966 The first of 850,000 Coho salmon were planted in the Platte River in Benzie County. Salmon stimulated fishing and helped the state deal with alewives that had entered the lakes through the Saint Lawrence Seaway. -

HST200. Michigan History

Washtenaw Community College Comprehensive Report HST 200 Michigan History Effective Term: Fall 2012 Course Cover Division: Humanities, Social and Behavioral Sciences Department: Social Science Discipline: History Course Number: 200 Org Number: 11740 Full Course Title: Michigan History Transcript Title: Michigan History Is Consultation with other department(s) required: No Publish in the Following: College Catalog , Time Schedule , Web Page Reason for Submission: Three Year Review / Assessment Report Change Information: Consultation with all departments affected by this course is required. Outcomes/Assessment Objectives/Evaluation Rationale: Update master syllabus to include student learning outcomes. Proposed Start Semester: Fall 2012 Course Description: The Michigan History course is a review and analysis of the social, economic and political history of the State of Michigan. Within the purview of the course is the study of the full extent of human experience, from contact with the indigenous peoples, through the arrival and implantation of European culture. The significant historical periods covered are Colonization, Territorial Years, Development from 1836 to 1861, Civil War and Post-War Development, the Progressive Era, World War I, the Great Depression, World War II and Post-War developments. This course can fulfill the Michigan history requirement for Teacher Certification in Social Studies (RX). Course Credit Hours Variable hours: No Credits: 3 Lecture Hours: Instructor: 45 Student: 45 Lab: Instructor: 0 Student: 0 Clinical: Instructor: -

Michigan-State University Benjamin

M‘ ~~nofim“‘~~m' O .‘o‘ '4. 9--a A POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE MACKINAC BRIDGE Thesis for the Degree 0? M; A MICHIGAN-STATE UNIVERSITY _ BENJAMIN. I. BURNS 1968 ILIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIZILIIIIIZIIIIIZIIII I/ 'a".*‘.*‘**" *“v'wfi-r ‘1 .IS .- a.- '1‘“ M". .. - ”V I I t IMAR (‘2 21” II m- :r ‘ " ’ ‘ ‘3‘: g I: 1“? I ‘ d' 10r"'= ‘ :99 ABSTRACT A POLITICAL HISTORY or TILE mat-mac BRIDGE The Mackinac Straits Bridge, which links Lichigan's two peninsulas is an imposing structure. Five miles long, it curves gracefully across the waters of the Great Lakes. Traffic moves swiftly and smoothly across its great length twelve months of the year. With a price tag of $100 million it is the product of man's imagination and a monument to man's persis- tance. The first proposals to bridge the Straits are found in Indian legends. Ever since the task of con- quering the travel barrier has colored man's thoughts. The concept of conneCting the two peninsulas traces thread-like down.through the pasn eighty years of Michigan's history. This is the story of the political loops and turns, knots and tangles in that thread. It is the story of the role and effect of the bridge in the politicalcampaigns of the twentieth century, which is pinpointed through analysis of election statistics. It is the story of Horatio Earle, Prentiss harsh Brown, Lmrray Van Wagoner, w.s. woodfill, and G, Lbnnen Williams, Although the bridge did not change the direction of Michigan political hiStory, it probably swayed its course simply because it was seized upon as an issue by candidates of every ilk and stripe. -

Beyond the Melting Pot the M.I.T

Beyond the Melting Pot THE M.I.T. PRESS PAPERBACK SERIES 1 Computers and the World of the Future 38 The Psycho-Blology of Language: An edited by Martin Greenberger Introduction to Dynamic Philology by 2 Experiencing Architecture by Steen George Kingsley ZIpf Eller Rasmussen 39 The Nature of Metals by Bruce A. 3 The Universe by Otto Struve Rogers 4 Word and Object by Willard Van 40 Mechanics, Molecular Physics, Hoat, and Orman Oulne Sound by R. A. Millikan, D. Roller, and E. C. Watson 5 Language, Thought, and Reality by Trees by Richard J. Benjamin Lee Whorf 41 North American Preston, Jr. 6 The Learner's Russian-English Dictionary and Golem, Inc. by Norbert Wiener by B. A. Lapidus and S. V. Shevtsova 42 God of H. H. Richardson 7 The Learner's English-Russian Dictionary 43 The Architecture and His Times by Henry-Russell by S. Folomkina and H. Weiser Hitchcock 8 Megalopolis by Jean Gottmann 44 Toward New Towns for America by 9 Time Series by Norbert Wiener Clarence Stein 10 Lectures on Ordinary Differential 45 Man's Struggle for Shelter In an Equations by Witold Hurewicz Urbanizing World by Charles Abrams 11 The image of the City by Kevin Lynch 46 Science and Economic Development by 12 The Sino-Soviet Rift by William E. Richard L. Meier Griffith 47 Human Learning by Edward Thorndike Pot by Nathan 13 Beyond the Melting 48 Pirotechnia by Vannoccio Biringuccio Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan 49 A Theory of Natural Philosophy by 14 A History of Western Technology by Roger Joseph Boscovich Friedrich Klemm 50 Bacterial Metabolism by Marjory Astronomy by Norman 15 The Dawn of Stephenson Lockyer 51 Generalized Harmonic Analysis and 16 Information Theory by Gordon Ralebeck Tauberlan Theorems by Norbert Wiener 17 The Tao of Science by R. -

The American Jew As Journalist Especially Pp

Victor Karady duction of antisemitic legislation by an ~ than earlier) in their fertility as well as ::ases of mixed marriages. For a study of see my articles, "Les Juifs de Hongrie :iologique," in Actes de La recherche en The American Jew as Journalist especially pp. 21-25; and "Vers une ]s: Ie cas de la nuptialite hongroise sous J.47-68. J. -oint Distribution Committee was quite Stephen Whitfield Jrevented by the establishment of soup (BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY) Along with this, the main task of the olished or destroyed Jewish institutions, -elped the non-Jewish poor, too. It is a g the end of the war it distributed at least :sky, "Hungary," p. 407). According to elp of the Joint up to the end of 1948 lillion worth of aid had been distributed The subject of the relationship of Jews to journalism is entangled in paradox. Their I. The scope of this aid was something role in the press has long been an obsession of their enemies, and the vastly lie, about 3,000 people were engaged in disproportionate power that Jews are alleged to wield through the media has long ve Jewish population (E. Duschinsky, been a staple of the antisemitic imagination. The commitment to this version of T, the Hungarian authorities gradually bigotry has dwarfed the interest that scholars have shown in this problem, and such -ompletely liquidated. _magyar zsid6sag 1945 es 1956 kozotti disparity merits the slight correction and compensation that this essay offers. ; Situation of Hungarian Jewry Between This feature of Judeophobia attains prominence for the first time in a significant ·rszagon [Jewry in Hungary After 1945] way in the squalid and murky origins of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the most ubiquitous of antisemitic documents. -

![Papers of W. Averell Harriman [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3626/papers-of-w-averell-harriman-finding-aid-library-of-congress-2863626.webp)

Papers of W. Averell Harriman [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

W. Averell Harriman A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Allan Teichroew with the assistance of Haley Barnett, Connie L. Cartledge, Paul Colton, Marie Friendly, Patrick Holyfield, Allyson H. Jackson, Patrick Kerwin, Mary A. Lacy, Sherralyn McCoy, John R. Monagle, Susie H. Moody, Sheri Shepherd, and Thelma Queen Revised by Connie L. Cartledge with the assistance of Karen Stuart Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2001 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2003 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003012 Latest revision: 2008 July Collection Summary Title: Papers of W. Averell Harriman Span Dates: 1869-1988 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1895-1986) ID No.: MSS61911 Creator: Harriman, W. Averell (William Averell), 1891-1986 Extent: 344,250 items; 1,108 containers plus 11 classified; 526.3 linear feet; 54 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Diplomat, entrepreneur, philanthropist, and politician. Correspondence, memoranda, family papers, business records, diplomatic accounts, speeches, statements and writings, photographs, and other papers documenting Harriman's career in business, finance, politics, and public service, particularly during the Franklin Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter presidential administrations. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Personal Names Abel, Elie. Acheson, Dean, 1893-1971. -

Secrets of the Ku Klux Klan Exposed by the World.” So Read the Headline Atop the Front Page of the New York World on 6 September 1921

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass History Publications Dept. of History 2015 Publicity and Prejudice: The ewN York World’s Exposé of 1921 and the History of the Second Ku Klux Klan John T. Kneebone Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/hist_pubs Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, History Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Copyright © 2015 John Kneebone Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/hist_pubs/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of History at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLICITY AND PREJUDICE: THE NEW YORK WORLD’S EXPOSÉ OF 1921 AND THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND KU KLUX KLAN John T. Kneebone, Ph.D. Department Chair and Assistant Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University “Secrets of the Ku Klux Klan Exposed By The World.” So read the headline atop the front page of the New York World on 6 September 1921. Twenty days and twenty front- page stories later, the World concluded its exposé with a proud headline declaring “Ku Klux Inequities Fully Proved.” By then more than two-dozen other papers across the country were publishing the World’s exposures, and, as Rodger Streitmatter puts it, “the series held more than 2 million readers spellbound each day.” The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, Inc., had become national news. Most contemporary observers agreed with the World that the now-visible Invisible Empire would not survive the attention.1 Predictions of the Klan’s demise proved premature. -

Gatsby: Myths and Realities of Long Island's North Shore Gold Coast.” the Nassau County Historical Society Journal 52 (1997):16–26

Previously published in The Nassau County Historical Society Journal. Revised and modified in July 2010 for website publication at www.spinzialongislandestates.com Please cite as: Spinzia, Raymond E. and Judith A. Spinzia. “Gatsby: Myths and Realities of Long Island's North Shore Gold Coast.” The Nassau County Historical Society Journal 52 (1997):16–26. Gatsby: Myths and Realities of Long Island’s North Shore Gold Coast by Raymond E. Spinzia and Judith A. Spinzia . The North Shore estates more than those of any other area of the Island captured the imagination of twentieth-century America. They occupied the area from Great Neck east to Centerport and from the Long Island Sound to just south of the present site of the Long Island Expressway. At the height of the estate era, Long Island had three Gold Coasts. An excellent social history of the South Shore estates, entitled Along the Great South Bay: From Oakdale to Babylon, has been written by Harry W. Havemeyer. The East End estates, which were built in the area known as the Hamptons, are chronicled by the authors in the soon-to-be-published Long Island’s Prominent Families in the Town of Southampton: Their Estates and Their Country Homes and Long Island’s Prominent Families in the Town of East Hampton: Their Estates and Their Country Homes. It is Long Island’s North Shore Gold Coast and the fact, fiction, and outright confusion created by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby that are considered here.1 Even the very existence of the South Shore and East End estates has remained relatively unknown.