Fred Miller, Pro Bowl Defensive Tackle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valuation of NFL Franchises

Valuation of NFL Franchises Author: Sam Hill Advisor: Connel Fullenkamp Acknowledgement: Samuel Veraldi Honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation with Distinction in Economics in Trinity College of Duke University Duke University Durham, North Carolina April 2010 1 Abstract This thesis will focus on the valuation of American professional sports teams, specifically teams in the National Football League (NFL). Its first goal is to analyze the growth rates in the prices paid for NFL teams throughout the history of the league. Second, it will analyze the determinants of franchise value, as represented by transactions involving NFL teams, using a simple ordinary-least-squares regression. It also creates a substantial data set that can provide a basis for future research. 2 Introduction This thesis will focus on the valuation of American professional sports teams, specifically teams in the National Football League (NFL). The finances of the NFL are unparalleled in all of professional sports. According to popular annual rankings published by Forbes Magazine (http://www.Forbes.com/2009/01/13/nfl-cowboys-yankees-biz-media- cx_tvr_0113values.html), NFL teams account for six of the world’s ten most valuable sports franchises, and the NFL is the only league in the world with an average team enterprise value of over $1 billion. In 2008, the combined revenue of the league’s 32 teams was approximately $7.6 billion, the majority of which came from the league’s television deals. Its other primary revenue sources include ticket sales, merchandise sales, and corporate sponsorships. The NFL is also known as the most popular professional sports league in the United States, and it has been at the forefront of innovation in the business of sports. -

ANNUAL UCLA FOOTBALL AWARDS Henry R

2005 UCLA FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE NON-PUBLISHED SUPPLEMENT UCLA CAREER LEADERS RUSHING PASSING Years TCB TYG YL NYG Avg Years Att Comp TD Yds Pct 1. Gaston Green 1984-87 708 3,884 153 3,731 5.27 1. Cade McNown 1995-98 1,250 694 68 10,708 .555 2. Freeman McNeil 1977-80 605 3,297 102 3,195 5.28 2. Tom Ramsey 1979-82 751 441 50 6,168 .587 3. DeShaun Foster 1998-01 722 3,454 260 3,194 4.42 3. Cory Paus 1999-02 816 439 42 6,877 .538 4. Karim Abdul-Jabbar 1992-95 608 3,341 159 3,182 5.23 4. Drew Olson 2002- 770 422 33 5,334 .548 5. Wendell Tyler 1973-76 526 3,240 59 3,181 6.04 5. Troy Aikman 1987-88 627 406 41 5,298 .648 6. Skip Hicks 1993-94, 96-97 638 3,373 233 3,140 4.92 6. Tommy Maddox 1990-91 670 391 33 5,363 .584 7. Theotis Brown 1976-78 526 2,954 40 2,914 5.54 7. Wayne Cook 1991-94 612 352 34 4,723 .575 8. Kevin Nelson 1980-83 574 2,687 104 2,583 4.50 8. Dennis Dummit 1969-70 552 289 29 4,356 .524 9. Kermit Johnson 1971-73 370 2,551 56 2,495 6.74 9. Gary Beban 1965-67 465 243 23 4,087 .522 10. Kevin Williams 1989-92 418 2,348 133 2,215 5.30 10. Matt Stevens 1983-86 431 231 16 2,931 .536 11. -

SCYF Football

Football 101 SCYF: Football is a full contact sport. We will help teach your child how to play the game of football. Football is a team sport. It takes 11 teammates working together to be successful. One mistake can ruin a perfect play. Because of this, we and every other football team practices fundamentals (how to do it) and running plays (what to do). A mistake learned from, is just another lesson in winning. The field • The playing field is 100 yards long. • It has stripes running across the field at five-yard intervals. • There are shorter lines, called hash marks, marking each one-yard interval. (not shown) • On each end of the playing field is an end zone (red section with diagonal lines) which extends ten yards. • The total field is 120 yards long and 160 feet wide. • Located on the very back line of each end zone is a goal post. • The spot where the end zone meets the playing field is called the goal line. • The spot where the end zone meets the out of bounds area is the end line. • The yardage from the goal line is marked at ten-yard intervals, up to the 50-yard line, which is in the center of the field. The Objective of the Game The object of the game is to outscore your opponent by advancing the football into their end zone for as many touchdowns as possible while holding them to as few as possible. There are other ways of scoring, but a touchdown is usually the prime objective. -

Bubba Smith: All Too Real

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 18, No. 2 (1996) BUBBA SMITH: ALL TOO REAL by Mike Gershman "When hearing tales of Bubba Smith, You wonder, is he man or myth?" -- Ogden Nash Quarterbacks who faced a charging Charles "Bubba" Smith generally found him -- at 6'8", 280 pounds -- all too real. A legend in East Lansing, Smith was a two-time All-America at Michigan State and an All-Pro before a freak accident hampered his effectiveness and shortened his playing career. He was born in Beaumont, Texas, and his father, coach Willie Ray Smith, bred three All-State Smiths -- Willie Ray, Jr., Tody, and Bubba. Willie Ray, Sr., made Charlton Pollard a perennial power in Texas school football; the school was 11-0 Bubba's senior year, and recruiters wore out the rugs in the Smith household until he decided on MSU. As a sophomore, he starred on a team that yielded just 76 points in eleven games. In 1965, MSU beat UCLA, 13-3, shut out Penn State, 23-0, and held Michigan to minus 51 yards rushing. Before the Ohio State game, Buckeye coach Woody Hayes warned that his team would run directly at Bubba; Smith stuffed the running attack, and MSU won, 32-7. The Spartans beat Notre Dame, 12-3, in South Bend to finish unbeaten but lost a Rose Bowl rematch to UCLA, 14-12. Despite the loss, Smith was called "the Deacon Jones of the college ranks" and was a consensus All-America selection. In 1966, Michigan State won its first nine games. The day before MSU was to play undefeated Notre Dame for the national championship, Smith roared by the Irish practice and was jailed on the eve of the Big Game. -

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER the Following Players Comprise the 1967 Season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER The following players comprise the 1967 season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. ATLANTA ATLANTA BALTIMORE BALTIMORE OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Tommy McDonald End: Sam Williams EB: Willie Richardson End: Ordell Braase Jerry Simmons TC OC Jim Norton Raymond Berry Roy Hilton Gary Barnes Bo Wood OC Ray Perkins Lou Michaels KA KOA PB Ron Smith TA TB OA Bobby Richards Jimmy Orr Bubba Smith Tackle: Errol Linden OC Bob Hughes Alex Hawkins Andy Stynchula Don Talbert OC Tackle: Karl Rubke Don Alley Tackle: Fred Miller Guard: Jim Simon Chuck Sieminski Tackle: Sam Ball Billy Ray Smith Lou Kirouac -

Football Rules

FOOTBALL RULES at-a-glance Weight Kick-Offs Nose Man QB Punts Play Clock Restrictions to Sneaks carry ball 4-5 N/A NO NO NO NO 40 sec Year Ball spotted on Offense keeps possession Olds 10 yd line until they score 6 <75 lbs NO NO NO 4 downs to get 1st down, then 45 sec Year Ball spotted on ball will be placed 25 yds down field but no deeper than Olds 20 yd line the 10 yd line 7-8 <100 lbs NO NO NO 4 downs to get 1st down, then 40 sec Year Ball spotted on ball will be placed 25 yds down field but no deeper than Olds 20 yd line the 10 yd line 9-10 <125 lbs YES From: NO NO 3 downs to get 1st then must 40 sec Year 40 yard line decide to go for it or punt. DEAD BALL except for punter Olds and returner. Ball will be spotted where returner controls the ball. 11-12 <150 lbs YES From: YES YES Whistle will make play “live” 30 sec Year 50 yard line after punter has control of long snap Olds (No Fakes) ALIGNMENT FOR: 6 year olds, 7-8 year olds, and 9-10 year olds Offensive Alignment: The offensive alignment of DPRD youth football leagues will consist of a center, two guards, two tackles and two ends. The offensive line will be balanced with a maximum split of 3 feet. The box is defined as behind and not outside the end offensive player OT/TE. -

UCLA Historical Journal

Book Reviews 141 Book Reviews William Gildea. Wben the Colts Belonged to Baltimore: A Father and a Son, A Team and a Time. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994 ViNCE BaGLI and NORMAN L. MacHT. Sundays at 2:00 with the Baltimore Colts. Centreville: Tidewater Publishers, 1995. ports history has been one of the most rapidly growing subdisciplines of J social and cultural history. Almost nonexistent as an academic field two decades ago, its practitioners have since generated a wide-ranging literature, and the usual scholarly apparatus journals and professional organizations. Yet, as is often the case scholars study a topic of popular interest, their work has done little to excite or engage the general reader. Sports histories written for the average fan focus on the great athletes, teams, and games. Academic histories try to imbed those sports in the social and cultural milieu of their community, explaining why they attract the interest they do, and how they shape public space. Recently, two books have appeared which bridge the gap between the popular and the scholarly. Ironically, both also focus on the same team-the former Baltimore Colts of the National Football League. William Gildea's When the Colts Belonged to Baltimore: A Father and a Son, A Team and a Time is a personal memoir of what the team meant to him. Gildea was a young boy when the Colts were created. His father was a busy manager for a chain of drug stores. Watching, discussing, and reading about sports were central to their shared father-son experiences. Gildea describes their autumn ritual of attending mass, and driving across Baltimore to Memorial Stadium, sharing insights into the upcoming game. -

Football Office

OOBLL Head Coach Denny Douds Sr. OL Michael Fleming Leads active NCAA coaches with 263 wins 3x All-PSAC East selection R-Sr. DL Marc Ranaudo 2016 All-PSAC East 1st team R-Sr. TB Jaymar Anderson 2018 2017 All-PSAC East 1st team THE UNIVERSITY ESU At A Glance Starters Returning/Lost ESU - Celebrating Location . East Stroudsburg, Pa . 125 Years of Service Offense President . Marcia G . Welsh, Ph .D . Founded in 1893 as a Normal School, East RETURNING (7): QB Ben Moser, Member . Pennsylvania State System Stroudsburg University has been offering quality TB Jaymar Anderson, WR Javier Buffalo, . .of Higher Education higher education to the citizens of Pennsylvania System Chancellor . Dr . Daniel Greenstein WR Jylil Reeder, LT Michael Fleming, for more than a century . Founded . 1893 LG Mike Nieman, RT Shane Trevorah With an enrollment of almost 7,000 Enrollment (Fall 2017) . 6,742 LOST (4): FB Wyatt Clements, students and a strong commitment to academic Athletics WR Tim Wilson, C Devon Ackerman, excellence, ESU’s programs continually earn the Affiliation . NCAA Division II RG Norman Rogers III highest levels of accreditation in their fields . Conference . PSAC The university’s most recently constructed . Pennsylvania State Athletic Conference Defense and largest academic building is the $40 million School Colors . Red and Black RETURNING (8*): DE Joseph Odebode (from Warren E . and Sandra Hoeffner Science and Team Nickname . Warriors 2016), NG Marc Ranaudo (from 2016), Technology Center, a state-of-the-art facility Athletic Director NG Joseph Ruggiero, CB Andre’ Gray, and the first new major academic building at Dr . Gary R . -

1961 Fleer Football Set Checklist

1961 FLEER FOOTBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Ed Brown ! 2 Rick Casares 3 Willie Galimore 4 Jim Dooley 5 Harlon Hill 6 Stan Jones 7 J.C. Caroline 8 Joe Fortunato 9 Doug Atkins 10 Milt Plum 11 Jim Brown 12 Bobby Mitchell 13 Ray Renfro 14 Gern Nagler 15 Jim Shofner 16 Vince Costello 17 Galen Fiss 18 Walt Michaels 19 Bob Gain 20 Mal Hammack 21 Frank Mestnik RC 22 Bobby Joe Conrad 23 John David Crow 24 Sonny Randle RC 25 Don Gillis 26 Jerry Norton 27 Bill Stacy 28 Leo Sugar 29 Frank Fuller 30 Johnny Unitas 31 Alan Ameche 32 Lenny Moore 33 Raymond Berry 34 Jim Mutscheller 35 Jim Parker 36 Bill Pellington 37 Gino Marchetti 38 Gene Lipscomb 39 Art Donovan 40 Eddie LeBaron 41 Don Meredith RC 42 Don McIlhenny Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 L.G. Dupre 44 Fred Dugan 45 Billy Howton 46 Duane Putnam 47 Gene Cronin 48 Jerry Tubbs 49 Clarence Peaks 50 Ted Dean RC 51 Tommy McDonald 52 Bill Barnes 53 Pete Retzlaff 54 Bobby Walston 55 Chuck Bednarik 56 Maxie Baughan RC 57 Bob Pellegrini 58 Jesse Richardson 59 John Brodie RC 60 J.D. Smith RB 61 Ray Norton RC 62 Monty Stickles RC 63 Bob St.Clair 64 Dave Baker 65 Abe Woodson 66 Matt Hazeltine 67 Leo Nomellini 68 Charley Conerly 69 Kyle Rote 70 Jack Stroud 71 Roosevelt Brown 72 Jim Patton 73 Erich Barnes 74 Sam Huff 75 Andy Robustelli 76 Dick Modzelewski 77 Roosevelt Grier 78 Earl Morrall 79 Jim Ninowski 80 Nick Pietrosante RC 81 Howard Cassady 82 Jim Gibbons 83 Gail Cogdill RC 84 Dick Lane 85 Yale Lary 86 Joe Schmidt 87 Darris McCord 88 Bart Starr 89 Jim Taylor Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© -

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set the Following Players Comprise the 1960 Season APBA Football Player Card Set

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set The following players comprise the 1960 season APBA Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. BALTIMORE 6-6 CHICAGO 5-6-1 CLEVELAND 8-3-1 DALLAS (N) 0-11-1 Offense Offense Offense Offense Wide Receiver: Raymond Berry Wide Receiver: Willard Dewveall Wide Receiver: Ray Renfro Wide Receiver: Billy Howton Jim Mutscheller Jim Dooley Rich Kreitling Fred Dugan (ET) Tackle: Jim Parker (G) Angelo Coia TC Fred Murphy Frank Clarke George Preas (G) Bo Farrington Leon Clarke (ET) Dick Bielski OC Sherman Plunkett Harlon Hill A.D. Williams Dave Sherer PA Guard: Art Spinney Tackle: Herman Lee (G-ET) Tackle: Dick Schafrath (G) Woodley Lewis Alex Sandusky Stan Fanning Mike McCormack (DT) Tackle: Bob Fry (G) Palmer Pyle Bob Wetoska (G-C) Gene Selawski (G) Paul Dickson Center: Buzz Nutter (LB) Guard: Stan Jones (T) Guard: Jim Ray Smith(T) Byron Bradfute Quarterback: Johnny Unitas Ted Karras (T) Gene Hickerson Dick Klein (DT) -

Scott Not Enough to Beat Duke Rape Reported Davis, Hill Spark Duke to Come-From-Behind 88-86 Triumph Near Hospital

THE CHRONICLE MONDAY, JANUARY 29, 1990 © DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 85, NO. 87 'Great' Scott not enough to beat Duke Rape reported Davis, Hill spark Duke to come-from-behind 88-86 triumph near hospital By MARK JAFFE From staff reports Sophomore Brian Davis and freshman A woman was beaten and raped near Thomas Hill spurred eighth-ranked Duke a parking garage across the street from to an exhilarating come-from-behind 88- Duke Hospital North on her way home 86 victory over 13th-ranked Georgia Tech from a local bar Friday night, accord Sunday afternoon at Cameron Indoor Sta ing to Duke Public Safety. dium. Georgia Tech's Dennis Scott led all On Saturday, Public Safety had a scorers with 36. suspect in custody for questioning, said "I hate to be redundant, but it was an Public Safety Capt. Robert Dean. How unbelievable game," said Duke head ever Dean would not release the man's coach Mike Krzyzewski, who has guided name pending the woman's decision to the Blue Devils to a 16-3 record (6-1 in the file charges. Atlantic Coast Conference). "This was a The woman left "Your Place or great basketball game with unbelievable Mine," a bar located at the corner of competitors on the floor for both squads." Erwin Road and Douglas Road, and "It was incredible," said Georgia Tech began walking along Erwin Road to head coach Bobby Cremins. "I don't know ward her apartment late Friday eve if we can play any better . We played ning, Dean said. -

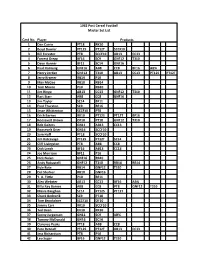

Master Set List

1962 Post Cereal Football Master Set List Card No. Player Products 1 Dan Currie PT18 RK10 2 Boyd Dowler PT12S PT12T SCCF10 3 Bill Forester PT8 SCCF10 AB13 CC13 4 Forrest Gregg BF16 SC9 GNF12 T310 5 Dave Hanner BF11 SC14 GNF16 6 Paul Hornung GNF16 AB8 CC8 BF16 AB¾ 7 Henry Jordan GNF12 T310 AB13 CC13 PT12S PT12T 8 Jerry Kramer RB14 P10 9 Max McGee RB10 RB14 10 Tom Moore P10 RB10 11 Jim Ringo AB13 CC13 GNF12 T310 12 Bart Starr AB8 CC8 GNF16 13 Jim Taylor SC14 BF11 14 Fred Thurston SC9 BF16 15 Jesse Whittenton SCCF10 PT8 16 Erich Barnes RK10 PT12S PT12T BF16 17 Roosevelt Brown OF10 PT18 GNF12 T310 18 Bob Gaiters GN11 AB13 CC13 19 Roosevelt Grier GN16 SCCF10 20 Sam Huff PT18 SCCF10 21 Jim Katcavage PT12S PT12T SC14 22 Cliff Livingston PT8 AB8 CC8 23 Dick Lynch BF16 AB13 CC13 24 Joe Morrison BF11 P10 25 Dick Nolan GNF16 RB10 26 Andy Robustelli GNF12 T310 RB14 RB14 27 Kyle Rote RB14 GNF12 T310 28 Del Shofner RB10 GNF16 29 Y. A. Tittle P10 BF11 30 Alex Webster AB13 CC13 BF16 AB¾ 31 Billy Ray Barnes AB8 CC8 PT8 GNF12 T310 32 Maxie Baughan SC14 PT12S PT12T 33 Chuck Bednarik SC9 PT18 34 Tom Brookshier SCCF10 OF10 35 Jimmy Carr RK10 SCCF10 36 Ted Dean OF10 RK10 37 Sonny Jurgenson GN11 SC9 AB¾ 38 Tommy McDonald GN16 SC14 39 Clarence Peaks PT18 AB8 CC8 40 Pete Retzlaff PT12S PT12T AB13 CC13 41 Jess Richardson PT8 P10 42 Leo Sugar BF16 GNF12 T310 43 Bobby Walston BF11 GNF16 44 Chuck Weber GNF16 RB10 45 Ed Khayat GNF12 T310 RB14 46 Howard Cassady RB14 BF11 47 Gail Cogdill RB10 BF16 48 Jim Gibbons P10 PT8 49 Bill Glass AB13 CC13 PT12S PT12T 50 Alex Karras