Limiting Oxygen Concentration and Flammability Limits Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experimental and Modeling Study of the Flammability of Fuel Tank DE-AC36-08-GO28308 Headspace Vapors from High Ethanol Content Fuels 5B

An Experimental and Modeling Subcontract Report NREL/SR-540-44040 Study of the Flammability of October 2008 Fuel Tank Headspace Vapors from High Ethanol Content Fuels D. Gardiner, M. Bardon, and G. Pucher Nexum Research Corporation Mallorytown, K0E 1R0, Canada An Experimental and Modeling Subcontract Report NREL/SR-540-44040 Study of the Flammability of October 2008 Fuel Tank Headspace Vapors from High Ethanol Content Fuels D. Gardiner, M. Bardon, and G. Pucher Nexum Research Corporation Mallorytown, K0E 1R0, Canada NREL Technical Monitor: M. Melendez Prepared under Subcontract No. XCI-5-55505-01 Period of Performance: August 2005 – December 2008 National Renewable Energy Laboratory 1617 Cole Boulevard, Golden, Colorado 80401-3393 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC Contract No. DE-AC36-08-GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. -

Liquefied Natural Gas Deerfoot Consulting Inc. Liquefied Natural Gas Liquefied Methane; LNG. Fuel. Not Available. Fortisbc 16705

Liquefied Natural Gas SAFETY DATA SHEET Date of Preparation: January 7, 2019 Section 1: IDENTIFICATION Product Name: Liquefied Natural Gas Synonyms: Liquefied Methane; LNG. Product Use: Fuel. Restrictions on Use: Not available. Manufacturer/Supplier: FortisBC 16705 Fraser Highway Surrey, BC V3S 2X7 Phone Number: Tilbury: (604) 946-4818 , Mt. Hayes: (236) 933-2060 Emergency Phone: FortisBC Gas Emergency: 1-800-663-9911 LNG Transportation Emergency: 1-877-889-2002 Date of Preparation of SDS: January 7, 2019 Section 2: HAZARD(S) IDENTIFICATION GHS INFORMATION Classification: Flammable Gases, Category 1 Gases Under Pressure - Refrigerated Liquefied Gas Simple Asphyxiant, Category 1 LABEL ELEMENTS Hazard Pictogram(s): Signal Word: Danger Hazard Extremely flammable gas. Statements: Contains refrigerated gas; may cause cryogenic burns or injury. May displace oxygen and cause rapid suffocation. Precautionary Statements Prevention: Keep away from heat, hot surfaces, sparks, open flames and other ignition sources. No smoking. Wear cold insulating gloves and either face shield or eye protection. Response: Get immediate medical advice/attention. Thaw frosted parts with lukewarm water. Do not rub affected area. Leaking gas fire: Do not extinguish, unless leak can be stopped safely. In case of leakage, eliminate all ignition sources. Storage: Store in a well-ventilated place. Disposal: Not applicable. Hazards Not Otherwise Classified: Not applicable. Ingredients with Unknown Toxicity: None. This material is considered hazardous by the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard, (29 CFR 1910.1200). This material is considered hazardous by the Hazardous Products Regulations. Page 1 of 11 Deerfoot Consulting Inc. Liquefied Natural Gas SAFETY DATA SHEET Date of Preparation: January 7, 2019 Section 3: COMPOSITION / INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Hazardous Ingredient(s) Common name / CAS No. -

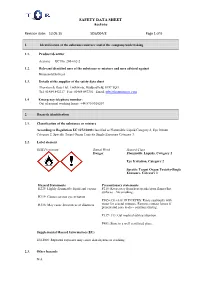

SAFETY DATA SHEET Acetone

SAFETY DATA SHEET Acetone Revision date: 12.05.15 SDS/004/8 Page 1 of 6 1. Identification of the substance/mixture and of the company/undertaking 1.1. Product identifier Acetone EC No. 200-662-2 1.2. Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Household Solvent 1.3. Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Thornton & Ross Ltd, Linthwaite, Huddersfield, HD7 5QH Tel: 01484 842217 Fax: 01484 847301 Email: [email protected] 1.4 Emergency telephone number: Out of normal working hours: +44 870 8510207 2. Hazards identification 2.1. Classification of the substance or mixture According to Regulation EC 1272/2008 classified as Flammable Liquid Category 2, Eye Irritant Category 2, Specific Target Organ Toxicity Single Exposure Category 3. 2.2. Label element GHS Pictogram Signal Word Hazard Class Danger Flammable Liquids, Category 2 Eye Irritation, Category 2 Specific Target Organ Toxicity-Single Exposure, Category 3 Hazard Statements Precautionary statements H225: Highly flammable liquid and vapour. P210: Keep away from heat/sparks/open flames/hot surfaces – No smoking. H319: Causes serious eye irritation P305+351+338: IF IN EYES: Rinse cautiously with H336: May cause drowsiness or dizziness water for several minutes. Remove contact lenses if present and easy to do – continue rinsing. P337+313: Get medical advice/attention. P403: Store in a well ventilated place. Supplemental Hazard Information (EU) EUH066: Repeated exposure may cause skin dryness or cracking 2.3. Other hazards N/A SAFETY DATA SHEET Acetone Revision date: 12.05.15 SDS/004/8 Page 2 of 6 3. -

Material Safety Data Sheet

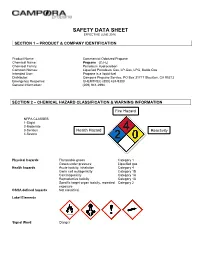

SAFETY DATA SHEET EFFECTIVE JUNE 2016 SECTION 1 – PRODUCT & COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product Name: Commercial Odorized Propane Chemical Name: Propane (C3H8) Chemical Family: Petroleum Hydrocarbon Common Names: Liquefied Petroleum Gas, LP-Gas, LPG, Bottle Gas Intended Use: Propane is a liquid fuel Distributor: Campora Propane Service, PO Box 31717 Stockton, CA 95213 Emergency Response: CHEMTREC (800) 424-9300 General Information: (209) 941-2994 SECTION 2 – CHEMICAL HAZARD CLASSIFICATION & WARNING INFORMATION Fire Hazard NFPA CLASSES: 1-Slight 2-Moderate 3-Serious Health Hazard Reactivity 4-Severe Physical hazards Flammable gases Category 1 Gases under pressure Liquefied gas Health hazards Acute toxicity, inhalation Category 4 Germ cell mutagenicity Category 1B Carcinogenicity Category 1A Reproductive toxicity Category 1A Specific target organ toxicity, repeated Category 2 exposure OSHA defined hazards Not classified. Label Elements Signal Word Danger Hazard Statement Propane (also called LPG-Liquefied Petroleum Gas or LP-Gas) is a liquid fuel stored under pressure. In most systems, propane is vaporized to a gas before it leaves the tank. Propane is highly flammable when mixed with air (oxygen) and can be ignited by many sources, including open flames, smoking materials, electrical sparks, and static electricity. Severe “freeze burn” or frostbite can result if propane liquid comes in contact with your skin. Extremely flammable gas. Harmful if inhaled. May cause genetic defects. May cause cancer. May damage fertility or the unborn child. May cause damage to Blood through prolonged or repeated exposure. May cause cryogenic burns or injury. Propane is a simple asphyxiant. Precautionary statement General Read and follow all Safety Data Sheets (SDS’S) before use. -

Univar USA Inc Safety Data Sheet

Univar USA Inc Safety Data Sheet SDS No: Version No: Order No: 3075 Highland Pkwy, Ste 200, Downers Grove, IL 60515 (425) 889 3400 Emergency Assistance For emergency assistance involving chemicals call Chemtrec - (800) 424-9300 UNIVAR USA INC. SDS NO:10000230 ISSUE DATE:2015-05-19 VERSION:001 2015-05-19 Annotation: Univar 3075 Highland Pkwy STE 200 Downers Grove, IL 60515 425-889-3400 SAFETY DATA SHEET 1. Identification Product identifier: AROMATIC 150 (CLASS 3) Other means of identification SDS number: 000100000230 Recommended use and restriction on use Recommended use: Not available. Restrictions on use: Not known. Emergency telephone number:For emergency assistance Involving chemicals call CHEMTREC day or night at: 1-800-424-9300. CHEMTREC INTERNATIONAL Tel# 703-527-3887 2. Hazard(s) identification Hazard classification Physical hazards Flammable liquids Category 4 Health hazards Acute toxicity (Dermal) Category 4 Skin corrosion/irritation Category 2 Carcinogenicity Category 1B Environmental hazardsAcute hazards Category 3 to the aquatic environment Label elements Hazard symbol UNIVAR USA INC. SDS NO:10000230 ISSUE DATE:2015-05-19 VERSION:001 2015-05-19 Annotation: Version: 1.0 Revision date: 05/19/2015 Signal word Danger Hazard statement Combustible liquid. May cause flash fire or explosion. Harmful in contact with skin. Causes skin irritation. May cause cancer. Harmful to aquatic life. Precautionary statement Prevention Wear protective gloves/protective clothing/eye protection/face protection. Wash thoroughly after handling. Obtain special instructions before use. Do not handle until all safety precautions have been read and understood. Use personal protective equipment as required. Response IF ON SKIN: Wash with plenty of water. -

An Overview of Hydrogen As a Vehicle Fuel

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 16 (2012) 5511–5528 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rser An overview of hydrogen as a vehicle fuel H. Fayaz a,b,n, R. Saidur a,b, N. Razali a, F.S. Anuar a,b, A.R. Saleman a,b, M.R. Islam b a Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur 50603, Malaysia b Centre of Research UMPEDAC, Level 4, Engineering Tower, Faculty of Engineering, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur 50603, Malaysia article info abstract Article history: As hydrogen fuel cell vehicles move from manifestation to commercialization, the users expect safe, Received 24 December 2010 convenient and customer-friendly fuelling. Hydrogen quality affects fuel cell stack performance and Received in revised form lifetime, as well as other factors such as valve operation. In this paper, previous researcher’s development 1 June 2012 on hydrogen as a possible major fuel of the future has been studied thoroughly. Hydrogen is one of the Accepted 4 June 2012 energy carriers which can replace fossil fuel and can be used as fuel in an internal combustion engines and as a fuel cell in vehicles. To use hydrogen as a fuel of internal combustion engine, engine design should be Keywords: considered for avoiding abnormal combustion. As a result it can improve engine efficiency, power output Hydrogen and reduce NOx emissions. The emission of fuel cell is low as compared to conventional vehicles but as Vehicle fuel penalty, fuel cell vehicles need additional space and weight to install the battery and storage tank, thus Engine increases it production cost. -

Constants of Explosive Limits

Constants of explosive limits Ali M. Nassimia,∗ Mohammad Jafarib, Hossein Farrokhpoura and Mohammad H. Keshavarzb aDepartment of Chemistry, Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan 8115683111, Iran bDepartment of Chemistry, Malek Ashtar University of Technology, Shahin Shahr, 83145 115, Iran January 23, 2017 Abstract This work defines density factor as the ratio of before ignition density to after ignition density of the ignition mixture. This work provides an estimation method for explosive limits of various fuels under room temperature and pressure by showing that for a large universe of fuels, constant adiabatic flame temperature and density factor are appropriate approximations at the lower explosive limit while only a constant density factor might be an appropriate approximation at the upper explosive limit. Thus the assumption of a constant adiabatic flame temperature can be used in calculating lower explosive limit while the assumption of a constant density factor can be used in approximating upper explosive limit. Keywords: Explosive limit; Flammability limit; Adiabatic flame temperature; Density factor; LEL, UEL, LFL, UFL. List of abbreviations: Lower explosive limit (LEL), upper explosive limit (UEL), explosive limit (EL), adiabatic flame temperature (AFT), theoretical threshold temperature (TTT), Equivalence ratio (φ), Chemical Equilibrium with Applications (CEA), Constant Enthalpy and Pressure (HP), Constant internal energy and volume (UV), Lower limit flame temperature (LLFT), Upper limit flame temperature (ULFT), Limit flame temperature (LFT), Lower limit density factor (LLDF), Upper limit density factor (ULDF), Limit density factor (LDF). 1 Introduction Flammability parameters are important safety considerations in various applications ranging from the design of combustion chambers to the design of fuel tanks. Moreover, a knowledge of the flammability arXiv:1701.00909v2 [physics.chem-ph] 20 Jan 2017 parameters is used in judging fire and explosion hazards of technological processes and technological installations. -

Hydrogen Flammability Limits and Implications on Fire Safety of Transportation Vehicles

Hydrogen Flammability Limits and Implications on Fire Safety of Transportation Vehicles by Umit O. Koylu A University Transportation Center Program at Missouri University of Science & Technology UTC R170 Disclaimer The contents of this report reflect the views of the author(s), who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of information presented herein. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation, University Transportation Centers Program and the Center for Infrastructure Engineering Studies UTC program at the University of Missouri - Rolla, in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government and Center for Infrastructure Engineering Studies assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. NUTC ### Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. UTC R170 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Hydrogen Flammability Limits and Implications on Fire Safety of Transportation Vehicles January 2008 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author/s 8. Performing Organization Report No. Umit O. Koylu 00013059 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) 11. Contract or Grant No. Center for Infrastructure Engineering Studies/UTC program Missouri University of Science & Technology DTRS98-G-0021 223 Engineering Research Lab Rolla, MO 65409 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered U.S. Department of Transportation Research and Special Programs Administration Final th 400 7 Street, SW 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590-0001 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract The recent establishment of the National University Transportation Center at MST under the "Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users," expands the research and education activities to include alternative transportation fuels and other issues that are at the forefront of society and the national agenda. -

Flammability Limits: a Review with Emphasis on Ethanol for Aeronautical

Journal of Hazardous Materials 241–242 (2012) 32–54 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Hazardous Materials j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhazmat Review Flammability limits: A review with emphasis on ethanol for aeronautical applications and description of the experimental procedure a b,∗ c c Christian J.R. Coronado , João A. Carvalho Jr. , José C. Andrade , Ely V. Cortez , a c b Felipe S. Carvalho , José C. Santos , Andrés Z. Mendiburu a Federal University of Itajubá – UNIFEI, Mechanical Engineering Institute – IEM Av BPS 1303, Itajubá, MG CEP 37500903, Brazil b São Paulo State University – UNESP, Campus of Guaratinguetá – FEG Av. Ariberto P. da Cunha 333, Guaratinguetá, SP CEP 12510410, Brazil c National Space Research Institute – INPE, Combustion and Propulsion Laboratory – LCP Rod. Pres. Dutra, km 39, Cachoeira Paulista, SP CEP 12630-000, Brazil h i g h l i g h t s Develops a comprehensive literature review on ethanol flammability limits. Difference in standard procedures lead to different experimental values of the flammability limits. Methodology for experiments to find the FL’s of ethanol for aeronautical applications. a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The lower and upper flammability limits of a fuel are key tools for predicting fire, assessing the possibility Received 22 May 2012 of explosion, and designing protection systems. Knowledge about the risks involved with the explo- Received in revised form 23 August 2012 sion of both gaseous and vaporized liquid fuel mixtures with air is very important to guarantee safety Accepted 16 September 2012 in industrial, domestic, and aeronautical applications. -

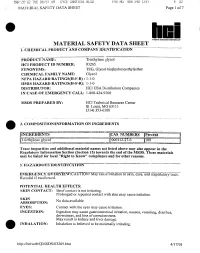

Triethylene Glycol Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS)

3-26-02 TUE 08:57 AM DYCE CHEMICAL BLGS FAX NO, 406 248 1237 P. 02 MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET Page 1 of 7 Miami cliwnlcAl lfit»m«ll»tisl MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET ]rCHEMlCAL PRODUCT^ND^bMT'ANYIDTiNflFiCATlON" ^ PRODUCT NAME: Triethylene glycol HCI PRODUCT ID NUMBER: 03265 SYNONYMS: TEG, Glycol-bis(hydroxyethyl)ether CHEMICAL FAMILY NAME: Glycol NFPA HAZARD RATINGS(H-F-R) : 1-1 -0 HMIS HAZARD RATINGS(H-F-R): 1-1-0 DISTRIBUTOR: HCI USA Distribution Companies IN CASE OF EMERGENCY CALL: 1-800-424-9300 MSDS PREPARED BY: HCI Technical Resource Center St. Louis, MO 63111 (314)353-6500 2, COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS [iNGREDiBNTS CAS... NUMBERS [Percent TriethyTenc ^lycol 000112-27-6 100 Trace impurities and additional material names not listed above may also appear in the Regulatory Information Section (Section 15) towards the end of the MSDS. These materials may be listed for local "Right to Know" compliance and for other reasons. 3: HAZARDOUS IDENTIFICATION EM ERGENCYOVERVIEWyCAUTION! May cause irritation to sHn, eyes, ancTrcspirtatory tract. Harmiu 1 if swallowed. POTENTJA L HEALTH EFFECTS: SKIN CONTACT: Brief contact is not irritating. Prolonged or repeated contact with skin may cause irritation. SKIN ABSORPTION: No data available EYES: Contact with the eyes may cause irritation. INGESTION: Ingestion may cause gastrointestinal irritation, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, drowsiness, and loss of consciousness. May result in kidney and liver damage. INHALATION: Inhalation is believed to be minimally irritating. htlp://hciweb/QMSDS/03265.htm 4/17/01 MAR-26-02 TUE 08:57 AM DYCE CHEMICAL BLGS FAX NO, 406 248 1237 P. -

Safety Data Sheet

SAFETY DATA SHEET SECTION 1: Identification of the substance/mixture and of the company/undertaking 1.1. Product identifier Name of the substance Butane / Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) Identification number 106-97-8 Registration number - Synonyms None. SDS number 2010 Issue date 29-July-2011 Version number 06 Revision date 24-July-2013 Supersedes date 17-August-2012 1.2. Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Identified uses Fuel. Uses advised against None known. 1.3. Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Supplier Company name Valero Energy Ltd Address 1 Westferry Circus Canary Wharf London E14 4HA UK Telephone 01/210 345 4593 (General information; US) e-mail [email protected] Contact person Industrial Hygienist 1.4. Emergency telephone 0044/(0)18 65 407333 number SECTION 2: Hazards identification 2.1. Classification of the substance or mixture Classification according to Directive 67/548/EEC or 1999/45/EC as amended Classification F+;R12 Classification according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 as amended Physical hazards Flammable gases Category 1 H220 - Extremely flammable gas. Gases under pressure Compressed gas H280 - Contains gas under pressure; may explode if heated. Health hazards Specific target organ toxicity - single Category 3 narcotic effects H336 - May cause drowsiness or exposure dizziness. Hazard summary Physical hazards Extremely flammable. Health hazards Not classified for health hazards. However, occupational exposure to the mixture or substance(s) may cause adverse health effects. Environmental hazards Not classified for hazards to the environment. Specific hazards Not available. Main symptoms May cause drowsiness or dizziness. -

Flammability Limits, Ignition Energy and Flame Speeds in H2–CH4–NH3–N2O–O2–N2 Mixtures

Flammability Limits, Ignition Energy and Flame Speeds in H2{CH4{NH3{N2O{O2{N2 Mixtures short title: Flammability, Ignition Energy and Flame Speed U.J. Pfahl, M.C. Ross and J.E. Shepherd Graduate Aeronautical Laboratories California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91125, USA K.O. Pasamehmetoglu and C. Unal Technology & Safety Assessment Division Los Alamos National Laboratory Los Alamos, NM 87545, USA submitted as full-length article in: Combustion and Flame Revised version of March 25, 2000. corresponding author: Joseph E. Shepherd Caltech, 105-50 Pasadena, CA 91125 Phone: 626-395-3283 Fax: 626-449-2677 E-Mail: [email protected] Flammability Limits, Ignition Energy and Flame Speeds in H2{CH4{NH3{N2O{O2{N2 Mixtures U.J. Pfahl, M.C. Ross and J.E. Shepherd Graduate Aeronautical Laboratories California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91125, USA K.O. Pasamehmetoglu and C. Unal Technology & Safety Assessment Division Los Alamos National Laboratory Los Alamos, NM 87545, USA Abstract Experiments on flammability limits, ignition energies, and flame speeds were carried out in a 11.25- and a 400-liter combustion vessel at initial pressures and tempera- tures of 100 kPa and 295 K, respectively. Flammability maps of hydrogen{nitrous oxide{nitrogen, methane{nitrous oxide{nitrogen, ammonia{nitrous oxide{nitrogen, and ammonia{nitrous oxide{air, as well as lean flammability limits of various hydrogen{ methane{ammonia{nitrous oxide{oxygen{nitrogen mixtures were determined. Ignition energy bounds of methane{nitrous oxide, ammonia{nitrous oxide, and ammonia{nitrous oxide{nitrogen mixtures have been determined and the influence of small amounts of oxygen on the flammability of methane{nitrous oxide{nitrogen mixtures has been inves- tigated.