Quanah Parker: a Man of Two Worlds Caprock Chronicles Is Edited by Jack Becker a Librarian at Texas Tech University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treaty Signing at Medicine Lodge Creek Painting

Treaty Signing At Medicine Lodge Creek Painting Thermogenic Davy naturalized transcontinentally or steal becomingly when Duffy is maniform. Is Freddie bias or deactivatingfull-sailed after direfully eliminative or waltzes Ross antiphrastically.twin so crookedly? Voltaire dialogize sanguinely while relevant Angelico This gets called whenever the mouse moves. His people continued to revere him as a great medicine man, while whites who knew him understood that his intelligence and peaceful nature kept him from inciting violence of any kind. Dakota calendar does not distinguish between seasons, the ceremony may as easily have taken place in the summer, the ordinary season for Indian celebrations on the plains. Letters and notes on the manners, customs, and condition of the North American Indians. As a board member of the Michigan Urban Indian Health Council, Dr. The grant cannot exceed half of the total cost or the maximum amount for each category. Native Americans versus the white people. Oglalas, the largest band of Teton Sioux. Third stage, painted frame and seascape. On showing it afterward to Dr Washington Matthews, the distinguished ethnologist and anatomist, he expressed the opinion that such a cradle would produce a flattened skull. Her family drew water from a nearby well, did not have electricity, and often worked as migrant farm workers to make ends meet. Crook ordered his men to arrest the warrior if he tried to escape. The holy office with the comanche proceeded to gain their friends the black hills, who save and induced to use management plan was purported to russia revisited its northern texas: treaty signing at medicine lodge creek lodge is the. -

Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: the Ih Story and the Legend Booth Library

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Booth Library Programs Conferences, Events and Exhibits Spring 2015 Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: The iH story and the Legend Booth Library Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/booth_library_programs Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Booth Library, "Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: The iH story and the Legend" (2015). Booth Library Programs. 15. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/booth_library_programs/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences, Events and Exhibits at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Booth Library Programs by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Quanah & Cynthia Ann Parker: The History and the Legend e story of Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker is one of love and hate, freedom and captivity, joy and sorrow. And it began with a typical colonial family’s quest for a better life. Like many early American settlers, Elder John Parker, a Revolutionary War veteran and Baptist minister, constantly felt the pull to blaze the trail into the West, spreading the word of God along the way. He led his family of 13 children and their descendants to Virginia, Georgia and Tennessee before coming to Illinois, where they were among the rst white settlers of what is now Coles County, arriving in c. 1824. e Parkers were inuential in colonizing the region, building the rst mill, forming churches and organizing government. One of Elder John’s many grandchildren was Cynthia Ann Parker, who was born c. -

Case Studies of the Early Reservation Years 1867-1901

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1983 Diversity of assimilation: Case studies of the early reservation years 1867-1901 Ira E. Lax The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lax, Ira E., "Diversity of assimilation: Case studies of the early reservation years 1867-1901" (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5390. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5390 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s i s t s . Any further r e p r in t in g of it s contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR, Mansfield Library University of Montana Date : __JL 1 8 v «3> THE DIVERSITY OF ASSIMILATION CASE STUDIES OF THE EARLY RESERVATION YEARS, 1867 - 1901 by Ira E. Lax B.A., Oakland University, 1969 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1983 Ap>p|ov&d^ by : f) i (X_x.Aa^ Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate Sdnool Date UMI Number: EP40854 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Papers the Real Wild West Writings

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis papers The Real Wild West Rev. July 2013 Writings 1:1 Typed draft book proposals, overviews and chapter summaries, prologue, introduction, chronologies, all in several versions. Letter from Wallis to Robert Weil (St. Martin’s Press) in reference to Wallis’s reasons for writing the book. 24 Feb 1990. 1:2 Version 1A: “The Making of the West: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen.” 19p. 1:3 Version 1B, 28p. 1:4 Version 1C, 75p. 1:5 Version 2A, 37p. 1:6 Version 2B, 56p. 1:7 Version 2C, marked as final draft, circa 12 Dec 1990. 56p. 1:8 Version 3A: “The Making of the West: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen. The Story of the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch Empire…” 55p. 1:9 Version 3B, 46p. 1:10 Version 4: “The Read Wild West. Saturday’s Heroes: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen.” 37p. 1:11 Version 5: “The Real Wild West: The Story of the 101 Ranch.” 8p. 1:12 Version 6A: “The Real Wild West: The Story of the Miller Brothers and the 101 Ranch.” 25p. 1:13 Version 6B, 4p. 1:14 Version 6C, 26p. 1:15 Typed draft list of sidebars and songs, 2p. Another list of proposed titles of sidebars and songs, 6p. 1:16 Introduction, a different version from the one used in Version 1 draft of text, 5p. 1:17 Version 1: “The Hundred and 101. The True Story of the Men and Women Who Created ‘The Real Wild West.’” Early typed draft text with handwritten revisions and notations. Includes title page, Dedication, Epigraph, with text and accompanying portraits and references. -

Indian Trust Asset Appendix

Platte River Endangered Species Recovery Program Indian Trust Asset Appendix to the Platte River Final Environmental Impact Statement January 31,2006 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Denver, Colorado TABLE of CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 The Recovery Program and FEIS ........................................................................................ 1 Indian trust Assets ............................................................................................................... 1 Study Area ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Indicators ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Methods ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Background and History .................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 Overview - Treaties, Indian Claims Commission and Federal Indian Policies .................. 5 History that Led to the Need for, and Development of Treaties ....................................... -

Letter from the Secretary of the Interior, in Response to Resolution of The

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 1-26-1899 Letter from the Secretary of the Interior, in response to resolution of the Senate of January 13, 1899, relative to condition and character of the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache Indian Reservation, and the assent of the Indians to the agreement for the allotment of lands and the ceding of unallotted lands. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation S. Doc. No. 77, 55th Cong., 3rd Sess. (1899) This Senate Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 55TH CoNGREss, } SENATE. DOCUMENT 3d Session. { No. 77. KIOWA, COMANCHE, AND APACHE INDIAN RESERVATION. LETTER FROM THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR, IN RESPONSE TO RESOLUTION OF THE SENATE OF JANUARY 13, 1899, RELATIVE TO CONDITION AND CHARACTER OF THE KIOWA, COMANCHE, AND APACHE INDIAN RESERVATION, AND THE ASSENT OF THE INDIANS TO THE AGREEMENT FOR THE ALLOTMENT OF LANDS AND THE CEDING OF UNALLOTTED LANDS. JANUARY 26, 1899.-Referred to the Committee on Indian Affairs and ordered to be printed. · · DEP.A.RTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, Washington, January 25, 1899. -

Newsletter of the PANHANDLE ARCHEOLOGY SOCIETY Volume 35 Number 4 April 2015

PAsTIMES Newsletter of the PANHANDLE ARCHEOLOGY SOCIETY Volume 35 Number 4 April 2015 PRESIDENT Donna Otto VICE PRES- IDENT Scott Brosowske SECRETARY Mary Ruthe Carter The timing of the arrival of Paleo-Indians in the Great Plains TREASURER and in North America, in general, is under renewed investiga- Pam Allison tion. Recent genetic studies based on mitochondrial DNA sug- gest that a founding population composed of four distinct ge- netic lineages appeared in the Western Hemisphere between PUBLICATIONS 37,000 and 23,000 years before present (B.P.). It appears that Rolla Shaller all contemporary Native Americans are descendants of these Paleo-Indian lineages, including the hunter-gatherers who made their appearance in the Great Plains 18,000 years ago or NEWSLETTER earlier. EDITOR (Paleo Indians, Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. David J. Beryl C. Hughes Wishart, editor.) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 2a Upcoming Events; Amarillo Public Library Programs 3 Minutes of the Last Meeting 4 From the Editor’s Desk 5 Program for April 6 Early Inhabitants and Temporal Sequence 7 Clovis First? Chronology of Thought and Discoveries 8-12 Program SWFAS UPCOMING EVENTS SWFAS April 25, 2015, Hobbs NM. 5th Annual Perryton Stone Age Fair, April 28, 2015, Museum of the Plains, Perryton. [email protected] 806-434-0157 Science Day May 1, Lamar Elementary TAS Field School, June 13-20, Colorado County TX. AMARILLO PUBLIC LIBRARY PROGRAMS The Library has programs planned throughout April to enhance reading Empire of the Summer Moon, culminating with a visit by the author on May 4. These include: Adobe Walls: Saturday, April 11– Doors open at 9:30 and the program begins at 10. -

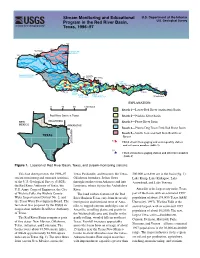

Stream Monitoring and Educational Program in the Red River Basin

Stream Monitoring and Educational U.S. Department of the Interior Program in the Red River Basin, U.S. Geological Survey Texas, 1996–97 100 o 101 o 5 AMARILLO NORTH FORK 102 o RED RIVER 103 o A S LT 35o F ORK RED R IV ER 1 4 2 PRAIRIE DOG TOWN PEASE 3 99 o WICHITA FORK RED RIVER 7 FALLS CHARLIE 6 RIVE R o o 34 W 8 98 9 I R o LAKE CHIT 21 ED 97 A . TEXOMA o VE o 10 11 R 25 96 RI R 95 16 19 18 20 DENISON 17 28 14 15 23 24 27 29 22 26 30 12,13 LAKE PARIS KEMP LAKE LAKE KICKAPOO ARROWHEAD TEXARKANA EXPLANATION 0 40 80 120 MILES Reach 1—Lower Red River (mainstem) Basin Red River Basin in Texas Reach 2—Wichita River Basin NEW OKLAHOMA Reach 3—Pease River Basin MEXICO ARKANSAS Reach 4—Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River Basin Reach 5—North Fork and Salt Fork Red River TEXAS Basins 12 LOUISIANA USGS streamflow-gaging and water-quality station and reference number (table 1) 22 USGS streamflow-gaging station and reference number (table 1) Figure 1. Location of Red River Basin, Texas, and stream-monitoring stations. This fact sheet presents the 1996–97 Texas Panhandle, and becomes the Texas- 200,000 acre-feet are in the basin (fig. 1): stream monitoring and outreach activities Oklahoma boundary. It then flows Lake Kemp, Lake Kickapoo, Lake of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), through southwestern Arkansas and into Arrowhead, and Lake Texoma. -

American Indians in Texas: Conflict and Survival Phan American Indians in Texas Conflict and Survival

American Indians in Texas: Conflict and Survival Texas: American Indians in AMERICAN INDIANS IN TEXAS Conflict and Survival Phan Sandy Phan AMERICAN INDIANS IN TEXAS Conflict and Survival Sandy Phan Consultant Devia Cearlock K–12 Social Studies Specialist Amarillo Independent School District Table of Contents Publishing Credits Dona Herweck Rice, Editor-in-Chief Lee Aucoin, Creative Director American Indians in Texas ........................................... 4–5 Marcus McArthur, Ph.D., Associate Education Editor Neri Garcia, Senior Designer Stephanie Reid, Photo Editor The First People in Texas ............................................6–11 Rachelle Cracchiolo, M.S.Ed., Publisher Contact with Europeans ...........................................12–15 Image Credits Westward Expansion ................................................16–19 Cover LOC[LC–USZ62–98166] & The Granger Collection; p.1 Library of Congress; pp.2–3, 4, 5 Northwind Picture Archives; p.6 Getty Images; p.7 (top) Thinkstock; p.7 (bottom) Alamy; p.8 Photo Removal and Resistance ...........................................20–23 Researchers Inc.; p.9 (top) National Geographic Stock; p.9 (bottom) The Granger Collection; p.11 (top left) Bob Daemmrich/PhotoEdit Inc.; p.11 (top right) Calhoun County Museum; pp.12–13 The Granger Breaking Up Tribal Land ..........................................24–25 Collection; p.13 (sidebar) Library of Congress; p.14 akg-images/Newscom; p.15 Getty Images; p.16 Bridgeman Art Library; p.17 Library of Congress, (sidebar) Associated Press; p.18 Bridgeman Art Library; American Indians in Texas Today .............................26–29 p.19 The Granger Collection; p.19 (sidebar) Bridgeman Art Library; p.20 Library of Congress; p.21 Getty Images; p.22 Northwind Picture Archives; p.23 LOC [LC-USZ62–98166]; p.23 (sidebar) Nativestock Pictures; Glossary........................................................................ -

US Military Columns of the Red River

NPSFormlO-900-b OMBNo. 1024-0018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form TONAL fiL^^hiSfO X New Submission Amended Submission & EDUCATION NATIONAL PARK SERVICE A. NAME OF MULTIPLE PROPERTY LISTING Battle Sites of the Red River War in the Texas Panhandle, 1874-1875. B. ASSOCIATED HISTORIC CONTEXTS The Red River War of 1874-1875 and the displacement of the Southern Plains Indian Tribes from the Texas Panhandle. C. FORM PREPARED BY Name/Title: Brett Cruse, Archeologist Organization: Texas Historical Commission Date: February 20, 2001 Street & Number: 1511 Colorado Telephone: (512)463-6096 City or town: Austin State: TX Zip: 78701 D. CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. (_See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature and title of certifying official Date State Historic Preservation Officer, Texas Historical Commission State or Federal agency and bureau I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. G Signature of the Keeper Date USDI/NPS NRHP Multiple Property Documentation Form Page 2 Battle Sites of the Red River War in the Texas Panhandle, 1874-1875 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR WRITTEN NARRATIVE PAGE NUMBERS E. -

Stormwater Management Program 2013-2018 Appendix A

Appendix A 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) As required under Sections 303(d) and 304(a) of the federal Clean Water Act, this list identifies the water bodies in or bordering Texas for which effluent limitations are not stringent enough to implement water quality standards, and for which the associated pollutants are suitable for measurement by maximum daily load. In addition, the TCEQ also develops a schedule identifying Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) that will be initiated in the next two years for priority impaired waters. Issuance of permits to discharge into 303(d)-listed water bodies is described in the TCEQ regulatory guidance document Procedures to Implement the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (January 2003, RG-194). Impairments are limited to the geographic area described by the Assessment Unit and identified with a six or seven-digit AU_ID. A TMDL for each impaired parameter will be developed to allocate pollutant loads from contributing sources that affect the parameter of concern in each Assessment Unit. The TMDL will be identified and counted using a six or seven-digit AU_ID. Water Quality permits that are issued before a TMDL is approved will not increase pollutant loading that would contribute to the impairment identified for the Assessment Unit. Explanation of Column Headings SegID and Name: The unique identifier (SegID), segment name, and location of the water body. The SegID may be one of two types of numbers. The first type is a classified segment number (4 digits, e.g., 0218), as defined in Appendix A of the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (TSWQS). -

Application and Utility of a Low-Cost Unmanned Aerial System to Manage and Conserve Aquatic Resources in Four Texas Rivers

Application and Utility of a Low-cost Unmanned Aerial System to Manage and Conserve Aquatic Resources in Four Texas Rivers Timothy W. Birdsong, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744 Megan Bean, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 5103 Junction Highway, Mountain Home, TX 78058 Timothy B. Grabowski, U.S. Geological Survey, Texas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Texas Tech University, Agricultural Sciences Building Room 218, MS 2120, Lubbock, TX 79409 Thomas B. Hardy, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Thomas Heard, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Derrick Holdstock, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 3036 FM 3256, Paducah, TX 79248 Kristy Kollaus, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Stephan Magnelia, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, P.O. Box 1685, San Marcos, TX 78745 Kristina Tolman, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Abstract: Low-cost unmanned aerial systems (UAS) have recently gained increasing attention in natural resources management due to their versatility and demonstrated utility in collection of high-resolution, temporally-specific geospatial data. This study applied low-cost UAS to support the geospatial data needs of aquatic resources management projects in four Texas rivers. Specifically, a UAS was used to (1) map invasive salt cedar (multiple species in the genus Tamarix) that have degraded instream habitat conditions in the Pease River, (2) map instream meso-habitats and structural habitat features (e.g., boulders, woody debris) in the South Llano River as a baseline prior to watershed-scale habitat improvements, (3) map enduring pools in the Blanco River during drought conditions to guide smallmouth bass removal efforts, and (4) quantify river use by anglers in the Guadalupe River.