10-Year Housing & Homelessness Plan Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regular Meeting - September 17, 2015

Meeting Book - Sudbury & District Board of Health - Regular Meeting - September 17, 2015 1.0 CALL TO ORDER - Page 7 2.0 ROLL CALL - Page 8 3.0 REVIEW OF AGENDA AND DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST - Page 9 - Page 14 4.0 DELEGATION / PRESENTATION Presentation by: Stacey Laforest, Director Environmental Health i) Blue-Green Algae Page 15 5.0 MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING i) Fourth Meeting - June 18, 2015 Page 16 MOTION: Approval of Minutes Page 28 6.0 BUSINESS ARISING FROM MINUTES - Page 29 7.0 REPORT OF THE MEDICAL OFFICER OF HEALTH AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER September 2015 Page 30 Board Self-Evaluation Page 43 Year-to-Date Financial Statements - July 31, 2015 Page 44 MOTION: Acceptance of Reports Page 47 Page 1 of 334 8.0 NEW BUSINESS i) Items for Discussion - Page 48 a) Alcohol and Substance Misuse - The Impact of Alcohol Poster Page 49 - Briefing Note from the Medical Officer of Health and Chief Page 50 Executive Officer to the Board Chair dated September 10, 2015 - Report to the Sudbury & District Board of Health: Page 51 Addressing substance misuse in Sudbury & District Health Unit service area, September 10, 2015 - The Sudbury & District Health Unit Alcohol Use and the Page 56 Health of Our Community Report b) Expansion of Proactive Disclosure System - Briefing Note from the Medical Officer of Health and Chief Page 90 Executive Officer to the Board Chair dated September 10, 2015 MOTION: Expansion of Proactive Disclosure System Page 92 c) Provincial Public Health Funding Letter from the Minister of Health and Long-Term Care to the -

Waterfront Regeneration on Ontario’S Great Lakes

2017 State of the Trail Leading the Movement for Waterfront Regeneration on Ontario’s Great Lakes Waterfront Regeneration Trust: 416-943-8080 waterfronttrail.org Protect, Connect and Celebrate The Great Lakes form the largest group of freshwater During the 2016 consultations hosted by the lakes on earth, containing 21% of the world’s surface International Joint Commission on the Great Lakes, the freshwater. They are unique to Ontario and one of Trail was recognized as a success for its role as both Canada’s most precious resources. Our partnership is a catalyst for waterfront regeneration and the way the helping to share that resource with the world. public sees first-hand the progress and challenges facing the Great Lakes. Driven by a commitment to making our Great Lakes’ waterfronts healthy and vibrant places to live, work Over time, we will have a Trail that guides people across and visit, we are working together with municipalities, all of Ontario’s Great Lakes and gives residents and agencies, conservation authorities, senior visitors alike, an opportunity to reconnect with one of governments and our funders to create the most distinguishing features of Canada and the The Great Lakes Waterfront Trail. world. In 2017 we will celebrate Canada’s 150th Birthday by – David Crombie, Founder and Board Member, launching the first northern leg of the Trail between Waterfront Regeneration Trust Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury along the Lake Huron North Channel, commencing work to close the gap between Espanola and Grand Bend, and expanding around Georgian Bay. Lake Superior Lac Superior Sault Garden River Ste. -

Freedom Liberty

2013 ACCESS AND PRIVACY Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner Ontario, Canada FREEDOM & LIBERTY 2013 STATISTICS In free and open societies, governments must be accessible and transparent to their citizens. TABLE OF CONTENTS Requests by the Public ...................................... 1 Provincial Compliance ..................................... 3 Municipal Compliance ................................... 12 Appeals .............................................................. 26 Privacy Complaints .......................................... 38 Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) .................................. 41 As I look back on the past years of the IPC, I feel that Ontarians can be assured that this office has grown into a first-class agency, known around the world for demonstrating innovation and leadership, in the fields of both access and privacy. STATISTICS 4 1 REQUESTS BY THE PUBLIC UNDER FIPPA/MFIPPA There were 55,760 freedom of information (FOI) requests filed across Ontario in 2013, nearly a 6% increase over 2012 where 52,831 were filed TOTAL FOI REQUESTS FILED BY JURISDICTION AND RECORDS TYPE Personal Information General Records Total Municipal 16,995 17,334 34,329 Provincial 7,029 14,402 21,431 Total 24,024 31,736 55,760 TOTAL FOI REQUESTS COMPLETED BY JURISDICTION AND RECORDS TYPE Personal Information General Records Total Municipal 16,726 17,304 34,030 Provincial 6,825 13,996 20,821 Total 23,551 31,300 54,851 TOTAL FOI REQUESTS COMPLETED BY SOURCE AND JURISDICTION Municipal Provincial Total -

Source Water Protection First Annual Progress Report

June 27th, 2018 City of Greater Sudbury 200 Brady St. Sudbury, ON P3A 5P3 Re: Source Water Protection First Annual Progress Report The First Annual Progress Report for the Sudbury Source Protection Plan was submitted to the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change on May 1st, 2018. It has been three years since the plan was implemented, and this report helps evaluate the effectiveness of the plan and its policies. The Sudbury Source Protection Authority receives annual reports from implementing bodies including The City of Greater Sudbury, The Municipality of Markstay-Warren, Public Health Sudbury and Districts, and Provincial Ministries. The information provided in these reports helps inform the Annual Progress Report. Please find the First Annual Progress Report attached, any questions or comments may be directed to the undersigned. Sincerely, Madison Keegans, Program Manager Drinking Water Source Protection Program [email protected] 705-674-5249 (x.210) 04/27/2018 This annual progress report outlines the progress made in implementing the source protection plan for The Greater Sudbury Protection Area, as required by the Clean Water Act and regulations. Given that this is our first annual report, the progress outlined includes all activities since the Source Protection Plans adoption in 2015. The SPC arrived at the score of Satisfactory on achieving source protection plan objectives for this reporting period since there has been some progress made but there is room for improvement moving forward. The progress of completing the Risk Management Plans is limited, however the SPC understands that there are constraints that implementing bodies are working to overcome. -

Guide to Government Supports

Ministry of Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade Revision Update: August 12th, 2020 @ 4:30PM Table of Contents COVID-19 – Provincial Government – Ontario’s Action Plan –Economic and Fiscal Update – Support for Businesses and Individuals 2. August 12th - Ontario Provides Update to Ontario's Action Plan: Responding to COVID- 1. Ontario Releases 2020-21 First Quarter 19 Finances 3. March 25th - Ontario's Action Plan: Responding to COVID-19 (March 2020 Economic and Fiscal Update) COVID-19 – Provincial Government – Support for Businesses 8. July 31st - Ontario Implementing Additional Measures at Bars and Restaurants to Help 2. August 12th - Ontario Providing Municipalities Limit the Spread of COVID-19 with up to $1.6 Billion in First Round of Emergency Funding 9. July 27th - Historic Agreement Delivers up to $4 Billion to Support Municipalities and 3. August 7th - Ontario Continues on the Path of Transit Renewal, Growth, and Economic Recovery 10. July 24th - Ontario Announces Support for 4. August 6th - Canada and Ontario invest in York University's New Markham Centre roads and bridges, connecting rural Campus communities 11. July 23rd - Ontario Supports Indigenous 5. August 6th - Investing in the Future of Businesses During COVID-19 Ontario's Tourism Industry 12. July 22nd - Ontario Legislature Adjourns after 6. August 4th - Province Supporting Innovative Significant Sitting in Response to COVID-19 Made-in-Ontario Technology to Sanitize PPE 13. July 22nd - Canada and Ontario invest in 7. July 31st (Update)- Ontario-Canada bridges and a road for rural communities in Emergency Commercial Rent Assistance Southern Ontario Program - Ontario Provides Urgent Relief for Small Businesses and Landlords – 14. -

Ontario Gazette Volume 148 Issue 17, La Gazette De L'ontario Volume 148

Vol. 148-17 Toronto ISSN 00302937 Saturday, 25 April 2015 Le samedi 25 avril 2015 Serving and filing an objection may be by hand delivery, mail, courier or Ontario Highway Transport Board facsimile. Serving means the date received by a party and filing means the date received by the Board. Periodically, temporary applications are filed with the Board. Details of these applications can be made available at anytime to any interested LES LIBELLÉS DÉS DEMANDES PUBLIÉES CI-DESSOUS SONT parties by calling (416) 326-6732. AUSSI DISPONIBLES EN FRANÇAIS SUR DEMANDE. The following are applications for extra-provincial and public vehicle Pour obtenir de l’information en français, veuillez communiquer avec la operating licenses filed under the Motor Vehicle Transport Act, 1987, Commission des transports routiers au 416-326-6732. and the Public Vehicles Act. All information pertaining to the applicant i.e. business plan, supporting evidence, etc. is on file at the Board and is Jorgensen, Jennifer A. 47634 available upon request. 083020 Swamp Hollow Road, Hilliardton, ON P0J 1L0 For the transportation of passengers on a chartered trip from points in the Any interested person who has an economic interest in the outcome of City of Temiskaming Shores, the Towns of Cobalt and Englehart, and the these applications may serve and file an objection within 29 days of this Townships of Armstrong, Casey, Hilliard, and James. publication. The objector shall: PROVIDED THAT the licensee be restricted to the use of Class “D” public vehicles as defined in paragraph (a) (iv) of subsection 1 of Section 7 of 1. -

OAHS and Rental Developments

OAHSOAHS andand RentalRental DevelopmentsDevelopments OAHS Northeastern Ontario Office TEMAGAMI 12 /0 /0 ALGOMA SUDBURY*# GREATER SUDBURY MATTAWA NAIRN AND HYMAN 3 /24 /0 8 /0 /0 2 /0 /0 MARKSTAY-WARREN 5 /0 /0 WEST NIPISSING BLIND RIVER ST.-CHARLES 40 /0 /0 BALDWIN 5 /14 /0 7 /0 /0 URON SHORES 2 /0 /0 BONFIELD 8 /0 /0 THE NORTH SHORE SPANISH PAPINEAU-CAMERON SABLES-SPANISH RIVERS EAST FERRIS 6 /0 /0 5 /0 /0 7 /0 /0 13 /0 /0 17 /0 /0 NIPISSING 4 /0 /0 HEAD, CLARA AND MARIA DEEP RIVER FRENCH RIVER 1 /0 /0 8 /0 /0 KILLARNEY 12 /0 /0 5 /0 /0 POWASSAN 2 /0 /0 MCCONKEY LAURENTIAN HILLS GORE BAY NORTHEASTERN 4 /0 /0 8 /0 /0 EAST MILLS 4 /0 /0 MANITOULIN AND THE ISLANDS 22 /0 /0 5 /0 /0 SOUTH RIVER BILLINGS MANITOULIN 5 /0 /0 6 /0 /0 WALLBRIDGE ASSIGINACK 3 /0 /0 BURK'S FALLS CENTRAL MANITOULIN 9 /0 /0 4 /0 /0 WHITEWATER REGION KILLALOE, 5 /0 /0 PARRY NORTH ALGONA 2 /0 /0 MAGNETAWAN ARMOUR HAGARTY & KEARNEY WILBERFORCE SOUND 7 /0 /0 1 /0 /0 RICHARDS CHAMPLAIN 2 /0 /0 5 /0 /0 1 /0 /0 1 /0 /0 PERRY SOUTH RENFREW PRESCOTT & CARLING MCDOUGALL 4 /0 /0 ALGONQUIN ALGONQUIN BONNECHERE VALLEY 2 /0 /0 4 /0 /0 LAKE OF BAYS 6 /0 /0 RUSSELL 9 /0 /0 HIGHLANDS 24 /0 /0 3 /0 /0 BRUDENELL, NORTH GLENGARRY SEGUIN HUNTSVILLE LYNDOCH & GREATER MADAWASKA 1 /0 /0 3 /0 /0 9 /0 /0 HASTINGS RAGLAN DYSART ET AL 1 /0 /0 PARRY SOUND HIGHLANDS CARLOW 4 /0 /0 NORTH STORMONT NORTHERN 18 /0 /0 OTTAWA 1 /0 /0 5 /0 /0 MAYO LANARK 1 /0 /0 BRUCE 0 /28 /0 MUSKOKA LAKES 1 /0 /0 LANARK HIGHLANDS PENINSULA LENNOX & SMITHS FALLS 4 /0 /0 HALIBURTON 13 /0 /0 STORMONT, DUNDAS AND GLENGARRY -

![Regular Council Meeting [9:00 A.M.] - Tuesday, January 12, 2021 [] Teleconference](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3527/regular-council-meeting-9-00-a-m-tuesday-january-12-2021-teleconference-1523527.webp)

Regular Council Meeting [9:00 A.M.] - Tuesday, January 12, 2021 [] Teleconference

AGENDA Regular Council Meeting [9:00 a.m.] - Tuesday, January 12, 2021 [] Teleconference Teleconference Details Dial: 519 -518-3600 Enter Access Code: 331398 Page 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 3. PUBLIC RECOGNITION / PRESENTATIONS None 4. DISCLOSURE OF PECUNIARY INTEREST 5. ADOPTION OF MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING(S) 6 - 15 5.1. December 8, 2020 6. PUBLIC MEETINGS / HEARINGS 6.1 The Municipal Act None 6.2 The Drainage Act 16 - 18 6.2.1 9:00 am Court of Revision - Reconvene Re: Harrison Drain 2020 Revised Assessment Page 1 of 195 6.3 The Planning Act None 6.4 Other None 7. DELEGATIONS None 8. CORRESPONDENCE 19 - 20 8.1. Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services Re: Reducing Poverty in Ontario 21 8.2. Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks Re: Minsters Annual Report on Drinking water 2020 and 2019-2020 Chief Drinking Water Inspector Annual Report 22 - 23 8.3. Township of Nairn and Hyman Re: Closure of Non-Essential Businesses during the Pandemic 24 - 25 8.4. Municipality of Southwest Middlesex Re: Municipal Drainage Works and Need for Coordination with National Railways 26 - 27 8.5. Town of Carleton Place Re: Request to Prioritize Children and Childcare as Part of Post Pandemic Recovery 28 - 29 8.6. Township of Matachewan Re: Request for Longer Application Periods for Grant Submission 30 - 32 8.7. Town of Kingsville Re: Letter of Support for Small Business 33 - 53 8.8. Tyler Zacher-King Re: Request for a Mask / Face Covering By-law Page 2 of 195 9. -

Lake Huron North Channel : Section 6

Lake Huron North Channel : Section 6 p i v R a a er iver l n Rushbrook i Capreol R s h i v Cartier R Val 84 Legend / Légende e i Levack r v 8 Therese e Han awhide a r Waterfront Trail - On-road / Sur la route Washrooms / Washrooms 810 Onaping Lake u P Blezard Valley x r r S o Waterfront Trail - Off-road / Hors route e e 15 r a v Chelmsford Val Ca $ Commercial Area / Zone commerciale v b i i n y Lake ssagi l Wind Waterfront Trail - Gravel road / e aux c R s 86 Route en gravier i Dowling 35 80 Railway Crossing / Passage à niveau a h Azilda P s l i 55 Waterfront Trail - Proposed / Proposée P r n Copper Cliff o 8 a a 1 A Roofed Accommodation / Hébergement avec toiture p 24 v r Fairbank 5 S Alerts / Alertes Quirke k i * n Lively 12 Su Lake c $ Commercial Area / Zone commerciale i 5.0 Distance / Distance (km) Sables a 15 55 l Worthington liot Lake P High Falls 4 Naughton Other Trails - Routes / a Agnew D'autres pistes - Routes Wifi / Wifi 8 r k Lake Turbine Whitefish 42 Whitefish Lake Superior Water Trail / 38 10 Sec 553 Birch L. 17 Lake Sentier maritime du lac Supérieur Restaurants / Restaurants McKerrow 13Nairn Centre McVit Panache Hospital / Hôpital Webbwood Lake Burwa Serpent Chutes HCR Espanola LCBO Liquor Control Board of Ontario / Régie des alcools de l'Ontario River 12 Killarney Lakelands Attraction / Attraction Walford and Headwaters Beach / Plage Border Crossing / Poste de frontière gge Cutler 66 Massey 225 Spanish 53 Sagamok Willisville Parc provincial Campground / Camping Conservation Area / Zone de protection de la nature Killarney -

Lacloche Foothills Municipal Association Agenda

LACLOCHE FOOTHILLS MUNICIPAL ASSOCIATION AGENDA/ MEETING REPORT Town of Espanola - Dec. 2, 2019 Main Level Boardroom 9:00 a.m. PRESENT: Chair Mayor, Laurier Falldien, Nairn & Hyman Mayor, Jill Beer, Town of Espanola Mayor, Les Gamble, Sables-Spanish Rivers Mayor, Vern Gorham, Baldwin Deputy Mayor, Bill Foster, Espanola Councillor, Arnelda Bennett, Sagamok Staff: Karin Bates, Belinda Ketchabaw, Kim Sloss, Cynthia Townsend 1. Ontario Provincial Police Staff Sergeant Helena Wall will be in attendance for introductions and discussions. We welcome Ms. Wall to our area. Due to scheduling conflicts Megan Cavanagh A/Inspector Detachment Commander attended in place of Staff Sergeant Helena Wall. It was indicated that if the municipalities needed to review individual municipal quarterly reports to call the detachment office. 2. Manitoulin-Sudbury District Services Board Robert Smith will attend to speak regarding a possible joint effort between the Manitoulin-Sudbury District Services Board and our municipalities to develop the Community Safety and Well Being Plans that are required to be in place by January 1, 2021. Robert Smith, Chief of Paramedic Services at Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB and Donna Stewart, Director of Integrated Social Services at Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB attended. -Through a power-point presentation the requirements for the development of the Community Safety and Well Being Plans were reviewed. The intent of the legislation is to identify specific community needs/risks and formulate prevention strategies, response mitigation actions, and incident reaction plans. The plans must include engagement from different sectors such as Health Agencies, Mental Health Agencies, Educational Services, Community and Social Services, Children and Youth Services, Police Services and ideally Indigenous, Senior and Youth Groups. -

Ontario Early Years Child and Family Centre Plan

Manitoulin-Sudbury District Services Board Ontario Early Years Child and Family Centres (OEYCFC) OEYCFC Plan and Local Needs Assessment Summary 2017 Geographic Distinction Reference The catchment area of the Manitoulin-Sudbury District Services Board (Manitoulin- Sudbury DSB) includes 38 communities, towns and villages and covers a distance that spans over 42,542 square kilometres. The communities, towns and villages are represented by 18 municipal jurisdictions and 2 unorganized areas, Sudbury Unorganized North Part and Manitoulin Unorganized West Part. The catchment area of the Manitoulin- Sudbury DSB is a provincially designated area for the purposes of the delivery of social services. The municipalities represented by the Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB are: Baldwin, Espanola, Nairn and Hyman, Sables-Spanish River, Assiginack, Billings, Burpee and Mills, Central Manitoulin, Cockburn Island, Gordon/Barrie Island, Gore Bay, Northeastern Manitoulin and the Islands, Tehkummah, French River, Killarney, Markstay- Warren, St. Charles and Chapleau. The municipalities in the Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB catchment area are commonly grouped into four main areas or regions, known as LaCloche, Manitoulin Island, Sudbury East and Sudbury North. The Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB catchment area does not include First Nations territories. Data for this report has been derived, for the most part, from Statistics Canada. We have used the most recent data (2016) whenever possible and have used 2011 data where the 2016 data is not yet available. From a Statistics Canada perspective, data for the catchment area of the Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB falls within two Census Divisions, Manitoulin District and Sudbury District. Manitoulin District and Sudbury District Census Divisions: The Manitoulin District – otherwise known as Manitoulin Island – includes 10 census subdivisions containing 14 communities, town and villages, and one unorganized territory. -

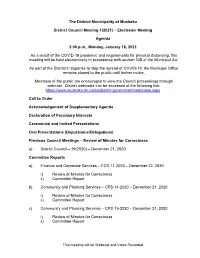

Council Minutes – Review of Minutes for Correctness

The District Municipality of Muskoka District Council Meeting 1(2021) – Electronic Meeting Agenda 3:00 p.m., Monday, January 18, 2021 As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and requirements for physical distancing, this meeting will be held electronically in accordance with section 238 of the Municipal Act. As part of the District's response to stop the spread of COVID-19, the Municipal Office remains closed to the public until further notice. Members of the public are encouraged to view the Council proceedings through webcast. District webcasts can be accessed at the following link: https://www.muskoka.on.ca/en/district-government/webcasts.aspx Call to Order Acknowledgement of Supplementary Agenda Declaration of Pecuniary Interests Ceremonial and Invited Presentations Oral Presentations (Deputations/Delegations) Previous Council Meetings – Review of Minutes for Correctness a) District Council – 19(2020) – December 21, 2020 Committee Reports a) Finance and Corporate Services – FCS-11-2020 – December 22, 2020 i) Review of Minutes for Correctness ii) Committee Report b) Community and Planning Services – CPS-14-2020 – December 21, 2020 i) Review of Minutes for Correctness ii) Committee Report c) Community and Planning Services – CPS-15-2020 – December 21, 2020 i) Review of Minutes for Correctness ii) Committee Report This meeting will be Webcast and Video Recorded Correspondence/Written Submissions All correspondence listed is a matter of public record. Should any member of Council or the public wish to receive full copies, please contact the Clerk’s department. Motions Councillors S. Clement and P. Kelly requested that the following motion be considered by Council: Moved by S.