Reconnaissance Excavations on Early Historic Fortifications and Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten MacGregor, Martin (2009) Gaelic barbarity and Scottish identity in the later Middle Ages. In: Broun, Dauvit and MacGregor, Martin(eds.) Mìorun mòr nan Gall, 'The great ill-will of the Lowlander'? Lowland perceptions of the Highlands, medieval and modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, pp. 7-48. ISBN 978085261820X Copyright © 2009 University of Glasgow A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/91508/ Deposited on: 24 February 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages MARTIN MACGREGOR One point of reasonably clear consensus among Scottish historians during the twentieth century was that a ‘Highland/Lowland divide’ came into being in the second half of the fourteenth century. The terminus post quem and lynchpin of their evidence was the following passage from the beginning of Book II chapter 9 in John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, which they dated variously from the 1360s to the 1390s:1 The character of the Scots however varies according to the difference in language. For they have two languages, namely the Scottish language (lingua Scotica) and the Teutonic language (lingua Theutonica). -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Martello Towers Research Project

Martello Towers Research Project March 2008 Jason Bolton MA MIAI IHBC www.boltonconsultancy.com Conservation Consultant [email protected] Executive Summary “Billy Pitt had them built, Buck Mulligan said, when the French were on the sea”, Ulysses, James Joyce. The „Martello Towers Research Project‟ was commissioned by Fingal County Council and Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council, with the support of The Heritage Council, in order to collate all known documentation relating to the Martello Towers of the Dublin area, including those in Bray, Co. Wicklow. The project was also supported by Dublin City Council and Wicklow County Council. Martello Towers are one of the most well-known fortifications in the world, with examples found throughout Ireland, the United Kingdom and along the trade routes to Africa, India and the Americas. The towers are typically squat, cylindrical, two-storey masonry towers positioned to defend a strategic section of coastline from an invading force, with a landward entrance at first-floor level defended by a machicolation, and mounting one or more cannons to the rooftop gun platform. The Dublin series of towers, built 1804-1805, is the only group constructed to defend a capital city, and is the most complete group of towers still existing in the world. The report begins with contemporary accounts of the construction and significance of the original tower at Mortella Point in Corsica from 1563-5, to the famous attack on that tower in 1794, where a single engagement involving key officers in the British military became the catalyst for a global military architectural phenomenon. However, the design of the Dublin towers is not actually based on the Mortella Point tower. -

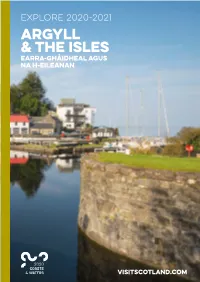

Argyll & the Isles

EXPLORE 2020-2021 ARGYLL & THE ISLES Earra-Ghàidheal agus na h-Eileanan visitscotland.com Contents The George Hotel 2 Argyll & The Isles at a glance 4 Scotland’s birthplace 6 Wild forests and exotic gardens 8 Island hopping 10 Outdoor playground 12 Natural larder 14 Year of Coasts and Waters 2020 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 Practical information 24 Places to visit 38 Leisure activities 40 Shopping Welcome to… 42 Food & drink 46 Tours ARGYLL 49 Transport “Classic French Cuisine combined with & THE ISLES 49 Events & festivals Fáilte gu Earra-Gháidheal ’s 50 Accommodation traditional Scottish style” na h-Eileanan 60 Regional map Extensive wine and whisky selection, Are you ready to fall head over heels in love? In Argyll & The Isles, you’ll find gorgeous scenery, irresistible cocktails and ales, quirky bedrooms and history and tranquil islands. This beautiful region is Scotland’s birthplace and you’ll see castles where live music every weekend ancient kings were crowned and monuments that are among the oldest in the UK. You should also be ready to be amazed by our incredibly Cover: Crinan Canal varied natural wonders, from beavers Above image: Loch Fyne and otters to minke whales and sea eagles. Credits: © VisitScotland. Town Hotel of the Year 2018 Once you’ve started exploring our Kenny Lam, Stuart Brunton, fascinating coast and hopping around our dozens of islands you might never Wild About Argyll / Kieran Duncan, want to stop. It’s time to be smitten! Paul Tomkins, John Duncan, Pub of the Year 2019 Richard Whitson, Shane Wasik/ Basking Shark Scotland, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh / Bar Dining Hotel of the Year 2019 Peter Clarke 20ARS Produced and published by APS Group Scotland (APS) in conjunction with VisitScotland (VS) and Highland News & Media (HNM). -

Isurium Brigantum

Isurium Brigantum an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough The authors and publisher wish to thank the following individuals and organisations for their help with this Isurium Brigantum publication: Historic England an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough Society of Antiquaries of London Thriplow Charitable Trust Faculty of Classics and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Chris and Jan Martins Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett with contributions by Jason Lucas, James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven Verdonck and Lacey Wallace Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries of London No. 81 For RWS Norfolk ‒ RF Contents First published 2020 by The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House List of figures vii Piccadilly Preface x London W1J 0BE Acknowledgements xi Summary xii www.sal.org.uk Résumé xiii © The Society of Antiquaries of London 2020 Zusammenfassung xiv Notes on referencing and archives xv ISBN: 978 0 8543 1301 3 British Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to this study 1 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data 1.2 Geographical setting 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the 1.3 Historical background 2 Library of Congress, Washington DC 1.4 Previous inferences on urban origins 6 The moral rights of Rose Ferraby, Martin Millett, Jason Lucas, 1.5 Textual evidence 7 James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven 1.6 History of the town 7 Verdonck and Lacey Wallace to be identified as the authors of 1.7 Previous archaeological work 8 this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Crannogs — These Small Man-Made Islands

PART I — INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION Islands attract attention.They sharpen people’s perceptions and create a tension in the landscape. Islands as symbols often create wish-images in the mind, sometimes drawing on the regenerative symbolism of water. This book is not about natural islands, nor is it really about crannogs — these small man-made islands. It is about the people who have used and lived on these crannogs over time.The tradition of island-building seems to have fairly deep roots, perhaps even going back to the Mesolithic, but the traces are not unambiguous.While crannogs in most cases have been understood in utilitarian terms as defended settlements and workshops for the wealthier parts of society, or as fishing platforms, this is not the whole story.I am interested in learning more about them than this.There are many other ways to defend property than to build islands, and there are many easier ways to fish. In this book I would like to explore why island-building made sense to people at different times. I also want to consider how the use of islands affects the way people perceive themselves and their landscape, in line with much contemporary interpretative archaeology,and how people have drawn on the landscape to create and maintain long-term social institutions as well as to bring about change. The book covers a long time-period, from the Mesolithic to the present. However, the geographical scope is narrow. It focuses on the region around Lough Gara in the north-west of Ireland and is built on substantial fieldwork in this area. -

Tarbert Castle

TARBERT CASTLE EXCAVATION PROJECT DESIGN March 2018 Roderick Regan Tarbert Castle: Our Castle of Kings A Community Archaeological Excavation. Many questions remain as to the origin of Tarbert castle, its development and its layout, while the function of many of its component features remain unclear. Also unclear is whether the remains of medieval royal burgh extend along the ridge to the south of the castle. A programme of community archaeological excavation would answer some of these questions, leading to a better interpretation, presentation and future protection of the castle, while promoting the castle as an important place through generated publicity and the excitement of local involvement. Several areas within the castle itself readily suggest areas of potential investigation, particularly the building ranges lining the inner bailey and the presumed entrance into the outer bailey. Beyond the castle to the south are evidence of ditches and terracing while anomalies detected during a previous geophysical survey suggest further fruitful areas of investigation, which might help establish the presence of the putative medieval burgh. A programme of archaeology involving the community of Tarbert would not only shed light on this important medieval monument but would help to ensure it remained a ‘very centrical place’ in the future. Kilmartin Museum Argyll, PA31 8RQ Tel: 01546 510 278 Email: http://www.kilmartin.org © 2018 Kilmartin Museum Company Ltd SC 022744. Kilmartin House Trading Co. Ltd. SC 166302 (Scotland) ii Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Tarbert Castle 5 2.1 Location and Topography 5 2.2 Historical Background 5 3 Archaeological and Background 5 3.1 Laser Survey 6 3.2 Geophysical Survey 6 3.3 Ground and Photographic Survey 6 3.4 Excavation 7 3.5 Watching Brief 7 3.6 Recorded Artefacts 7 4. -

December 2011 What a Night It Was!

No 6 Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year December 2011 What a night it was! If one of the signs of a great Ball is how quickly the evening passes, then this year St Andrew’s Day Ball would be one of the best ever. I’ve been to many of these events over the years and I have to say that this year’s ranks among the most memorable. The dance program was fun and varied, the food was excellent, the service from the Novotel Langley staff was great "Alba Gu Brath" and the Perth Metro Pipe Band showed why it is the best pipe band in WA at the moment. COMMITTEE 2011-2012 The traditional toasts presented by Mattie Turnbull and Darian Chieftain Ferguson were informative and entertaining. Ken Suttie I felt it was just a great package and almost everyone I talked Vice Chieftain to agreed. Jeff Crookes Most importantly, however, we had a group of guests who were Hon Secretary out to enjoy themselves and it was the way they took up the challenge that made the evening disappear in a flash. Brian McMurdo Hon Treasurer I need to congratulate the members of the Committee for their work in putting together the ingredients for such a great Ball, Diana Paxman with a special mention for Jeff Crookes and Reggie McNeill . Members —————— Susan Bogie You might be interested to know that for the last seven years Cameron Dickson I’ve been sending out St Andrew’s Day greetings by email, on Cheryl Hill behalf of our members, to St Andrew Societies and other Doris LaValette Scottish groups around the world. -

Download Download

ARTIFICIAL ISLAND SE HIGHLAN INTH 7 25 D AREA. II. FURTHER ARTIFICIAE NOTETH N SO L ISLAND HIGHE TH N -SI LAND AREA REVY B . OD.F O BLUNDELL, F.S.A.Scoi. previoun I s years several artificial islands have been describey db me in papers to this Society: thus the Proceedings for the year 1908 contain the description of Eilean Muireach in Loch Ness ; notices of e islande Beaulth th n i sy Firth n Loci , h Bruiach, Loch Moy, Loch Garry, Loch Lundi, Loch Oich, Loch Lochy Locd an , h Trei cone gar - tained in the volume for 1909 ; while that for 1910 includes a notice of the island in Loch nan Eala, Arisaig. At this date, in order to continue and extend the investigation, e Britisth h Association appointe a dCommitte e wit0 hgrana £1 f o t to defray incidental expenses. With a view to ascertaining what islands were thought to be artificial by persons dwelling in the near neighbourhood, this Committee issued a circular, of which 450 copies were sen t e replieoutTh . s were both numerou d interestingan s , thoug somn hi e cases informatio s suppliewa n d whic d alreadha h y been publishe n Di dr Stuart's admirable article publishe y thib d s Society in 1865, or in other occasional papers published since that date. The present paper will, I trust, be found to contain only original information, though som bees eha n incorporate abridgen a n di d form in the Report of the British Association. It seems, however, especially fitting that all the information available should be placed before the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. -

Blssii Great Lakes Maritime Institute

TELESCOPE May, 1966 Volume 15, Number 5 B lS S Ii Great Lakes Maritime Institute Dossin Great Lakes Museum, Belle Isle, Detroit 7, Michigan May May Cover: £ G e z in a B r ov i g Below, left: TELESCOPE Seaway Salties 4: Gosforth Below, right: Marg it Brovig Lists compiled by Donald Baut and George Ayoub - -Ma s sman with photographs by Emory Massman and others photographs LIST ONE: Compiled by FLAGS represented Be Belgium Gh Ghana No Norway Br Great Britain Gr Greece Pa Panama Donald Baut Ca Canada In India Sp Spain Da Denmark Ir Ireland Ss Switzerland Du Netherlands Is Israel Sw Sweden Fi Finland It Italy BAR United Arab Republic Fr France Ja Japan US United States Ge West Germany De Lebanon Yu Yugoslavia 1964 Li Liberia N U M B E R OF Atheltemplar (Br) Athel Line Ltd. 496x64 1951 0-1-0-2-2-1 PASSAGES Atlantic Duke (Li) Atlantic Tankers Ltd. 529x70 1952 0-0-0-0-0-3 Augvald (No) Skibs A/S Corona 467x61 1958 0-0-0-1-0-1 cO CO cO cO cO cO en O) oi O' O' O' iO O K to U Jk Baltic Sea (Sw) Wm. Thozen, Mgr. 444x56 1960 0-0-2-2-2-1 a Bambi (No) D/S A/S Bananfart 293x45 1957 1-2-3-1-0-1 A & J Faith (US) Pacific Seafarers Inc. 459x63 194 6 0-0-0-0-3-1 Bannercliff (Br) Bond Shipping Co. Ltd. 455x58 1948 0-0-0-0-1-1 A & J Mercury (US) Pacific Steamers Inc. -

Boult Ireland

SRCD.240 STEREO ADD JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Scherzo & Cortège (Julius Caesar) OULT Mai-Dun, symphonic rhapsody 1 (c1905) * (10’29”) B Tritons, symphonic prelude B conducts The Forgotten Rite, prelude 2 The Forgotten Rite, prelude (1918) (7’07”) Tritons, symphonic prelude 3 Mai-Dun, symphonic rhapsody (1920-21) (11’23”) Suite ‘The Overlanders’ 4 A London Overture (1936) (11’57”) A London Overture 5 Epic March (1942) (8’12”) RELAND Epic March (arr. Geoffrey Bush) (1942) * I Themes from Julius Caesar I 6 1. Scherzo (2’47”) 7 2. Cortège (3’58”) Suite ‘The Overlanders’ (1946-47) (ed. Charles Mackerras) * 8 1. March: Scorched Earth (4’39”) 9 2. Romance: Mary & Sailor (3’55”) 10 3. Intermezzo: Open Country (3’20”) 11 4. Scherzo: The Brumbies (4’22”) 12 5. Finale: Night Stampede (3’51”) (76’04”) London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Sir Adrian Boult The above individual timings will normally each include two pauses. One before the beginning of each movement or work, and one after the end. ൿ 1966 *ൿ 1971 The copyright in these sound recordings is owned by Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. This compilation and the digital remastering ൿ 2007 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. © 2007 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the UK LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive license from Lyrita by Wyastone Estate Ltd, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK London Philharmonic Orchestra movement; Romance). The Suite begins with the title music, which recurs with overwhelming effect at the end of the film when the herdsmen, against all odds, reach their destination. -

Gaelic Nova Scotia an Economic, Cultural, and Social Impact Study

Curatorial Report No. 97 GAELIC NOVA SCOTIA AN ECONOMIC, CULTURAL, AND SOCIAL IMPACT STUDY Michael Kennedy 1 Nova Scotia Museum Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada November 2002 Maps of Nova Scotia GAELIC NOVA SCOTIA AN ECONOMIC, CULTURAL, AND SOCIAL IMPACT STUDY Michael Kennedy Nova Scotia Museum Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada Nova Scotia Museum 1747 Summer Street Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3A6 © Crown copyright, Province of Nova Scotia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing from the Nova Scotia Museum, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Nova Scotia Museum at the above address. Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0-88871-774-1 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Section One: The Marginalization of Gaelic Celtic Roots 10 Gaelic Settlement of Nova Scotia 16 Gaelic Nova Scotia 21 The Status of Gaelic in the 19th Century 27 The Thin Edge of The Wedge: Education in 19th-Century Nova Scotia 39 Gaelic Language and Status: The 20th Century 63 The Multicultural Era: New Initiatives, Old Problems 91 The Current Status of Gaelic in Nova Scotia 112 Section Two: Gaelic Culture in Nova Scotia The Social Environment 115 Cultural Expression 128 Gaelic and the Modern Media 222 Gaelic Organizations 230 Section Three: Culture and Tourism The Community Approach 236 The Institutional Approach 237 Cultural Promotion 244 Section Four: The Gaelic Economy Events 261 Lessons 271 Products 272 Recording 273 Touring 273 Section Five: Looking Ahead Strengths of Gaelic Nova Scotia 275 Weaknesses 280 Opportunities 285 Threats 290 Priorities 295 Bibliography Selected Bibliography 318 INTRODUCTION Scope and Method Scottish Gaels are one of Nova Scotia’s largest ethnic groups, and Gaelic culture contributes tens of millions of dollars per year to the provincial economy.