The Bowman's Creek Branch of Lehigh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luzerne County Act 167 Phase II Stormwater Management Plan

Executive Summary Luzerne County Act 167 Phase II Stormwater Management Plan 613 Baltimore Drive, Suite 300 Wilkes-Barre, PA 18702 Voice: 570.821.1999 Fax: 570.821.1990 www.borton-lawson.com 3893 Adler Place, Suite 100 Bethlehem, PA 18017 Voice: 484.821.0470 Fax: 484.821.0474 Submitted to: Luzerne County Planning Commission 200 North River Street Wilkes-Barre, PA 18711 June 30, 2010 Project Number: 2008-2426-00 LUZERNE COUNTY STORMWATER MANAGEMENT PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY – INTRODUCTION 1. Introduction This Stormwater Management Plan has been developed for Luzerne County, Pennsylvania to comply with the requirements of the 1978 Pennsylvania Stormwater Management Act, Act 167. This Plan is the initial county-wide Stormwater Management Plan for Luzerne County, and serves as a Plan Update for the portions or all of six (6) watershed-based previously approved Act 167 Plans including: Bowman’s Creek (portion located in Luzerne County), Lackawanna River (portion located in Luzerne County), Mill Creek, Solomon’s Creek, Toby Creek, and Wapwallopen Creek. This report is developed to document the reasoning, methodologies, and requirements necessary to implement the Plan. The Plan covers legal, engineering, and municipal government topics which, combined, form the basis for implementation of a Stormwater Management Plan. It is the responsibility of the individual municipalities located within the County to adopt this Plan and the associated Ordinance to provide a consistent methodology for the management of stormwater throughout the County. The Plan was managed and administered by the Luzerne County Planning Commission in consultation with Borton-Lawson, Inc. The Luzerne County Planning Commission Project Manager was Nancy Snee. -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

Public Votes Loyalsock As PA River of the Year Perkiomen TU Leads

Winter 2018 Publication of the Pa. Council of Trout Unlimited www.patrout.org Perkiomen TU Students to leads restoration research brookies project on on Route 6 trek By Charlie Charlesworth namesake creek PATU President By Thomas W. Smith Perkiomen Valley TU President In summer 2018, six college students from our PATU 5 Rivers clubs will spend a The Perkiomen Valley Chapter of month trekking across Pennsylvania’s U.S. Trout Unlimited partnered with Sundance Route 6. Their purpose will be to explore, Creek Consulting, the Montgomery do research, collect data and still have time County Conservation District, Penn State do a little bit of fishing in the northern tier’s Master Watershed Stewards and Upper famed brook trout breeding grounds. Perkiomen High School for a stream They will be supported by the PA Fish restoration project on Perkiomen Creek, and Boat Commission, three colleges in- Contributed Photo which was carried out over five days in Volunteers work on a stream restora- cluding Mansfield, Keystone and hopefully See CREEK, page 7 tion project along Perkiomen Creek. See TREK, page 2 Public votes Loyalsock as PA River of the Year By Pennsylvania DCNR Home to legions of paddlers, anglers, and other outdoors enthusiasts in north central Pennsylvania, Loyalsock Creek has been voted the 2018 Pennsylvania River of the Year. The public was invited to vote online, choosing from among five waterways nominated across the state. Results were pariveroftheyear.org Photo See RIVER, page 2 Loyalsock Creek was voted 2018 Pennsylvania River of the Year. IN THIS ISSUE Keystone Coldwater Conference ..........................3 How to become a stream advocate.......................6 Headwaters .............................................................4 Minutes ....................................................................8 Treasurer’s Notes ...................................................5 Chapter Reports .................................................. -

Pub 315 NY Blocked

COMMUNITY INDEX for the 2019 Pennsylvania Tourism and Transportation Map www.penndot.gov PUB 315 (6-16) COUNTY COUNTY SEAT COUNTY COUNTY SEAT Adams Gettysburg . .P-11 Lackawanna Scranton....................V-5 Allegheny Pittsburgh . .D-9 Lancaster Lancaster ..................S-10 Armstrong Kittanning . .E-7 Lawrence New Castle................B-6 Beaver Beaver . .B-8 Lebanon Lebanon ....................S-9 Bedford Bedford . .J-10 Lehigh Allentown...................W-8 Berks Reading . .U-9 Luzerne Wilkes-Barre..............U-6 Blair Hollidaysburg . .K-9 Lycoming Williamsport...............P-6 Bradford Towanda . .S-3 McKean Smethport..................K-3 Bucks Doylestown . .X-9 Mercer Mercer.......................C-6 Butler Butler . .D-7 Mifflin Lewistown .................N-8 Cambria Ebensburg . .J-9 Monroe Stroudsburg...............X-7 Cameron Emporium . .L-4 Montgomery Norristown.................W-10 Carbon Jim Thorpe . .V-7 Montour Danville .....................R-7 Centre Bellefonte . .M-7 Northampton Easton.......................X-8 Chester West Chester . .V-11 Northumberland Sunbury.....................Q-7 Clarion Clarion . .F-6 Perry New Bloomfield .........P-9 Clearfield Clearfield . .K-6 Philadelphia Philadelphia...............X-11 Clinton Lock Haven . .O-6 Pike Milford .......................Y-5 Columbia Bloomsburg . .S-6 Potter Coudersport ..............L-3 Crawford Meadville . .C-4 Schuylkill Pottsville....................T-8 Cumberland Carlisle . .P-10 Snyder Middleburg ................P-7 Dauphin Harrisburg . .Q-9 Somerset Somerset...................G-10 Delaware Media . .W-11 Sullivan Laporte......................S-5 Elk Ridgway . .J-5 Susquehanna Montrose ...................U-3 Erie Erie . .C-2 Tioga Wellsboro ..................O-4 Fayette Uniontown . .E-11 Union Lewisburg..................Q-7 Forest Tionesta . .F-5 Venango Franklin .....................D-5 Franklin Chambersburg . .N-11 Warren Warren ......................G-3 Fulton McConnellsburg . .M-11 Washington Washington ...............C-10 Greene Waynesburg . -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

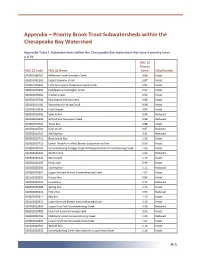

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96 -

Bowman Creek Supplemental Environmental Project

Bowman Creek Supplemental Environmental Project By: David L. McCormick, PE, D. WRE McCormick Engineering, LLC For: City of South Bend Department of Public Works January 2013 Bowman Creek Supplemental Environmental Project Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1. Review of Existing Water Quality Studies .......................................................................... 1 1.2. Field Investigation ............................................................................................................... 1 1.3. Evaluation of Improvement Alternatives ............................................................................. 2 1. Evaluation of Alternatives ................................................................................................... 2 2. Report and Recommendation Regarding Alternatives ....................................................... 2 2. REVIEW OF EXISTING WATER QUALITY STUDIES ..................................................... 2 2.1. Previous studies by the City of South Bend ....................................................................... 3 2.2. EPA Studies ........................................................................................................................ 3 2.3. Idem Studies ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.4. INDOT US 31 EIS .............................................................................................................. -

Massacre of Wyoming. Alonzo Chappel, 1828-1887

Massacre of Wyoming. Alonzo Chappel, 1828-1887 10 I. Benjamin Harvey: Frontier Years and Discovery Wyoming Conflict County, in Connecticut, was employed to transport supplies to the Wyoming settlement. Several of Hervey’s friends and lthough the first colonial settlement in the Wyoming neighbors from Connecticut planned to settle in the Wyoming Valley occurred in 1762, Harvey’s Lake was unknown frontier. Hostility between the Connecticut and Pennsylvania to the settlers until 1781, when it was discovered claimants to Wyoming soon erupted into armed conflict. The Aby accident. In 1662 King Charles II gave a charter to the first Yankee-Pennamite War ended when the Connecticut Connecticut Colony to certain lands in North America forces overtook the Pennsylvania defenders at Fort Wyoming in that included the Wyoming Valley. At the same time, King Wilkes-Barre in the summer of 1771. The apparent victory of Charles II owed a large debt to Admiral William Penn of the Connecticut drew additional Yankee settlers to Wyoming. The English navy, father of William Penn. In 1681 King Charles II regional warfare, initially between the conflicting settlements, granted William Penn a charter to the Pennsylvania region in but later between the American Colonies and England, served as repayment of the debt owed to Penn’s father. Inadvertently, the the catalyst for Benjamin Harvey’s discovery of Harvey’s Lake. Pennsylvania and Connecticut charters both covered a prized Susquehanna River valley known as Wyoming. Benjamin Harvey’s wife, Elizabeth, had died in Connecticut in December 1771, and a son, Seth, died a week An effort by Connecticut to settle the Wyoming region later at age twenty-three. -

Great Fall Fly Fishing Memories by Charles R. Meck

6 Pennsylvania Angler & Boater www.fish.state.pa.us by Charles R. Meck For years my fly fishing season ended with the white fly hatch on the Little Juniata River in central Pennsylvania or on the Yellow Breeches Creek near Carlisle. With the advent of Labor Day, I retired my fly fishing gear for another year. I usually rationalized that cooler weather made trout less active. I also believed that few streams held trout at the end of the season. How misinformed could I be? Many Pennsylvania trout streams hold ample numbers of trout at this time of year. Not until the past decade did I continue fly fishing any remaining hatches. For the past couple of years through fall. Trico hatches appear from late July through I’ve enjoyed those fly fishing outings more than those much of September. If no killing frost occurs early, the unpredictable high-water early spring trips. trico often continues. This hatch persuaded me to continue A few years ago, I told Craig Josephson of Johnstown fly fishing into autumn. about one of those great fall days of fishing I had just expe- I enjoyed those fall fishing trips matching that small rienced. In three days of autumn fly fishing, I caught and hatch and began to realize that trout didn’t stop feeding released 15 hefty brown trout. Two of those brown trout when fall arrived. In fact, I often found that trout feed more measured 16 inches and one went 19 inches. Another mea- aggressively in fall than they do earlier in the season. -

Remote Water Quality Monitoring Network Baseline Conditions 2010

Remote Water Quality Monitoring Network Data Report of Baseline Conditions for 2010 - 2012 A SUMMARY Susquehanna River Basin Commission Publication No. 292 December 2013 Abstract The Susquehanna River Basin process can impact the specific trend at Choconut Creek, and pH and Commission (SRBC) continuously conductance of a stream, while the temperature showing an increasing monitors water chemistry in select infrastructure (roads and pipelines) trend at Hammond Creek. Dissolved watersheds in the Susquehanna needed to make drilling possible in oxygen did not show a trend at any of River Basin undergoing shale gas remote watersheds may adversely the stations and Meshoppen Creek did drilling activity. Initiated in 2010, impact stream sediment loads. The not show a trend with any parameters. 58 monitoring stations are included monitoring stations were grouped The natural gas well density varies in the Remote Water Quality by Level III ecoregion with specific within the watersheds; Choconut Monitoring Network (RWQMN). conductance and turbidity analyzed Creek has no drilling activity, the Specific conductance, pH, turbidity, using box plots. Based on available Hammond Creek Watershed has less dissolved oxygen, and temperature data, land use, permitted dischargers, than one well per square mile, and are continuously monitored and and geology appear to play the greatest the well density in the Meshoppen additional water chemistry parameters role with influencing turbidity and Creek Watershed is almost three times (metals, nutrients, radionuclides, etc.) specific conductance. that of Hammond Creek. Although are collected at least four times a year. the analyses were only performed on These data provide a baseline dataset In order to determine if shale three stations, the results show the for smaller streams in the basin, which gas drilling and the associated importance of collecting enough data previously had little or no data. -

2021-02-02 010515__2021 Stocking Schedule All.Pdf

Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission 2021 Trout Stocking Schedule (as of 2/1/2021, visit fishandboat.com/stocking for changes) County Water Sec Stocking Date BRK BRO RB GD Meeting Place Mtg Time Upper Limit Lower Limit Adams Bermudian Creek 2 4/6/2021 X X Fairfield PO - SR 116 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 2 3/15/2021 X X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 4 3/15/2021 X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 GREENBRIAR ROAD BRIDGE (T-619) SR 94 BRIDGE (SR0094) Adams Conewago Creek 3 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 3 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 4 4/22/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 10/6/2021 X X Letterkenny Reservoir 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 5 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. -

Erosion and Sediment Pollution Control Plan Guide for Small Projects in Luzerne County

Erosion and Sediment Pollution Control Plan Guide For Small Projects in Luzerne County Conditions for use of this guide: • Total earth disturbance must be 0.5 acres or less to qualify. • Submissions not including a complete package (pages 1-17 of this document plus the District’s 2-page E&SCP Plan Review Application) will not be reviewed. • The District may request more detailed plans (i.e. engineered E&SPC plans), based on scope of earthwork being proposed. • Please include your municipal stormwater management permit application when submitting this guide to the District. 325 Smiths Pond Road Shavertown, PA 18708 570-674-7991 (phone) 570-674-7989 (fax) [email protected] www.luzernecd.org Rev. 9/2017 Introduction All earth disturbance activities in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania are regulated by the requirements of the erosion and sediment pollution control regulations found in Title 25, Chapter 102 of the Pennsylvania Code. All earth disturbance activities, including those that disturb less than 5,000 square feet, must implement and maintain Best Management Practices (BMPs) to control erosion and sediment pollution. A written Erosion and Sediment Pollution Control (E&SPC) Plan is required if one or more of the following apply: the total area of disturbance is 5,000 square feet or greater, or if the activity has the potential to discharge to a water classified as a High Quality (HQ) or Exceptional Value (EV) water published in Chapter 93 regulations (relating to water quality standards). This document is intended to assist in the development of an E&SPC Plan where the total area of earth disturbance is 5,000 square feet or greater and less than 21,780 square feet (half an acre) on slopes that are less than 10%.