EWT/ Eco Web Town Hardwicke Christopher & Hertel, Sean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Toronto's Middle Landscape: Spaces of Planning, Contestation, and Negotiation Robert Scott Fiedler a Dissertation S

RETHINKING TORONTO’S MIDDLE LANDSCAPE: SPACES OF PLANNING, CONTESTATION, AND NEGOTIATION ROBERT SCOTT FIEDLER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GEOGRAPHY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO May 2017 © Robert Scott Fiedler, 2017 Abstract This dissertation weaves together an examination of the concept and meanings of suburb and suburban, historical geographies of suburbs and suburbanization, and a detailed focus on Scarborough as a suburban space within Toronto in order to better understand postwar suburbanization and suburban change as it played out in a specific metropolitan context and locale. With Canada and the United States now thought to be suburban nations, critical suburban histories and studies of suburban problems are an important contribution to urbanistic discourse and human geographical scholarship. Though suburbanization is a global phenomenon and suburbs have a much longer history, the vast scale and explosive pace of suburban development after the Second World War has a powerful influence on how “suburb” and “suburban” are represented and understood. One powerful socio-spatial imaginary is evident in discourses on planning and politics in Toronto: the city-suburb or urban-suburban divide. An important contribution of this dissertation is to trace out how the city-suburban divide and meanings attached to “city” and “suburb” have been integral to the planning and politics that have shaped and continue to shape Scarborough and Toronto. The research employs an investigative approach influenced by Michel Foucault’s critical and effective histories and Bent Flyvbjerg’s methodological guidelines for phronetic social science. -

City Planning Division - Study Work Program Update

PH20.2 REPORT FOR ACTION City Planning Division - Study Work Program Update Date: January 5, 2021 To: Planning and Housing Committee From: Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning Wards: All SUMMARY This report provides the City Planning Division's annual update on its Study Work Program. It outlines the Division's 58 completions and approvals in 2020, highlighting a remarkable variety of city building work. The report also provides a forecast for the Division's 2021 Study Work Program. Although this past year has not been business as usual given COVID-19 impacts, the collaborative effort with divisions across the Toronto Public Service, external agencies and community partners enabled City Planning to advance studies and initiatives in support of the City's 2019 Corporate Strategic Plan and its four Strategic Priorities on affordable housing, mobility, quality of life, and climate change and resiliency. These include affordable housing policy and programs, such as inclusionary zoning and Housing Now; new planning frameworks to guide longer term investment and growth, for example, the Golden Mile and Keele Finch Plus secondary plans; zoning initiatives including expanding permissions for outdoor patios to support bars and restaurants as part of Toronto's recovery efforts; environmental initiatives such as the Ravine Implementation Strategy; and guidelines, including the Retail Design Manual, to influence better design and development outcomes across the city. Looking ahead, the 2021 Study Work Program reflects Council's direction -

![[Sub]Urban Place a Theory of Space, Place and the Suburbs by Michael](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9207/sub-urban-place-a-theory-of-space-place-and-the-suburbs-by-michael-1939207.webp)

[Sub]Urban Place a Theory of Space, Place and the Suburbs by Michael

An Adaptive [sub]Urban Place a theory of space, place and the suburbs by Michael LaPrade A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in M.Arch. Professional Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2011 Michael LaPrade Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre rGttrence ISBN: 978-0-494-81599-1 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-81599-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

966 Don Mills Road – City-Initiated Official Plan and Zoning By-Law Amendment Application – Final Report

REPORT FOR ACTION 966 Don Mills Road – City-Initiated Official Plan and Zoning By-law Amendment Application – Final Report Date: August 23, 2021 To: North York Community Council From: Acting Director, Community Planning, North York District Wards: 16 - Don Valley East Planning Application Number: 19 255599 NNY 16 OZ SUMMARY At its meeting of July 16, 17 and 18, 2019, City Council approved a community recreation centre accommodating a twin-pad arena/multi-sport indoor courts, gymnasium with walking track, an aquatic centre, and community and program space, co-located with a large community park at 844 Don Mills Road (the former Celestica lands) to serve the communities along Don Mills Road, from York Mills Road to Flemingdon Park. In order to implement this approval, City Council directed staff to initiate an Official Plan and Zoning By-law Amendment to modify zoning permissions for 966 Don Mills Road, located one kilometre north of 844 Don Mills Road, which had been previously approved to accommodate a community recreation centre. City Council further directed that staff undertake a review of other public and community uses that may be accommodated at 966 Don Mills Road through the execution of a Public and Community Needs Scan of the Broader Don Mills Catchment Area (the "Scan") to determine if any service gaps will exist following the completion of the recommended community recreation centre at 844 Don Mills Road. The purpose of the Scan was to assist in determining future public/community use(s) for the lands at 966 Don Mill Road. This amendment implements City Council's direction by recommending the removal of provisions related to the construction of a community recreation centre previously approved at 966 Don Mills Road included in current site specific official plan policies, zoning by-law provisions and a Section 37 agreement for the Shops at Don Mills. -

Changing Trends in the Canadian “Mallscape” of the 1950S and 1960S1

e ssaY | essai Changing Trends in The Canadian “mallsCape” of The 1950s and 1960s1 M Arie-JOSÉe TherrieN is an associate professor > Marie-JoSée at the Faculty of Liberal Studies, Ontario College therrien of Art and design University. She is an active researcher in the field of architectural and design history in both english- and French-speaking circles and has published on the architecture of Canadian he almost total absence of stud- embassies (Au-delà des frontières, l’architecture Ties on Canadian shopping malls by des ambassades canadiennes, Quebec, Presses architectural historians can partly be explained by the perceived lack of aes- de l’Université Laval, 2005) and on shopping malls thetic value of such buildings. With the in Ontario (“Shopping Malls in Postwar Ontario,” notable exception of Claude Bergeron, d OCOMOMO international Journal, March 2008). who contended in 1981 that “suburban in her recent research, she is focussing on the and regional cent[re]s have been almost emergence of “ethnic” shopping malls in the totally ignored by architectural historians suburbs of large Canadian cities as attempts to who have been more concerned with articulate new secular identities in the realm of styles than with planning,”2 Canadian our consumerist society. shopping centres have, to this day, not yet attracted the attention they deserve.3 Their reputation, in part tarnished by the fact that they have been perceived as major contributors to the erosion of the modern public space, does not help either. Judged before being analyzed for what they really are, shopping centres have been depicted on many occasions as the necessary evils of our consumer soci- ety. -

A Case Study of the Shops at Don Mills

Ryerson University Digital Commons @ Ryerson Theses and dissertations 1-1-2012 Lifestyle Centres: A Planner‘s Dream Or Nightmare? A Case Study Of The hopS s At Don Mills Lynn Duong Ryerson University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ryerson.ca/dissertations Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Duong, Lynn, "Lifestyle Centres: A Planner‘s Dream Or Nightmare? A Case Study Of The hopsS At Don Mills" (2012). Theses and dissertations. Paper 1318. This Major Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Ryerson. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ryerson. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIFESTYLE CENTRES: A PLANNER‘S DREAM OR NIGHTMARE? A CASE STUDY OF THE SHOPS AT DON MILLS by Lynn Duong, BES, University of Waterloo, 2010 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Planning in Urban Development Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2012 © Lynn Duong 2012 AUTHORS DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this major research paper. This is a true copy of the major research paper, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this major research paper to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research ___________________________________ Signature I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this major research paper by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. -

Toronto Toronto, ON

What’s Out There® Toronto Toronto, ON Welcome to What’s Out There Toronto, organized than 16,000 hectares. In the 1970s with urban renewal, the by The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) waterfront began to transition from an industrial landscape with invaluable support and guidance provided by to one with parks, retail, and housing—a transformation that numerous local partners. is ongoing. Today, alluding to its more than 1,400 parks and extensive system of ravines, Toronto is appropriately dubbed This guidebook provides fascinating details about the history the “City within a Park.” The diversity of public landscapes and design of just a sampling of Toronto’s unique ensemble of ranges from Picturesque and Victorian Gardenesque to Beaux vernacular and designed landscapes, historic sites, ravines, Arts, Modernist, and even Postmodernist. and waterfront spaces. The essays and photographs within these pages emerged from TCLF’s 2014 partnership with This guidebook is a complement to TCLF’s much more Professor Nina-Marie Lister at Ryerson University, whose comprehensive What’s Out There Toronto Guide, an interactive eighteen urban planning students spent a semester compiling online platform that includes all of the enclosed essays plus a list of Toronto’s significant landscapes and developing many others—as well overarching narratives, maps, and research about a diversity of sites, designers, and local themes. historic photographs— that elucidate the history of design The printing of this guidebook coincided with What’s Out There of the city’s extensive network of parks, open spaces, and Weekend Toronto, which took place in May 2015 and provided designed public landscapes. -

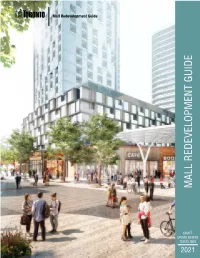

Mall Redevelopment Guide

Mall Redevelopment Guide MALL REDEVELOPMENT GUIDE DRAFT URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINES 2021 51 City of Toronto City Planning 2021 Mall Redevelopment Guide MALL REDEVELOPMENT GUIDE Image Credits Title Page: Rendering of Agincourt Mall redevelopment (by Giannone Petricone Associates for North American Development Group) Page 2: Aerial view of Shops at Don Mills (Toronto) looking southeast. Google Maps. Accessed 18 November 2020 Page 4: Yonge-Sheppard Centre & Yonge-Eglinton Centre photos provided by RioCan REIT, photo credit: Bob Gundum Page 8: Marine Gateway (Vancouver) https://www.pci-group.com/wp-content/uploads/Marine-Gateway3-July-2016-For-PCI-Web.jpg Page 9: Port Street Market (Mississauga) Creator: Philip Lengden; Copyright: © 2005 Philip Lengden; Information extracted from IPTC Photo Metadata Page 9: Square One Mall (Mississauga) https://renx.ca/investments-lift-square-one-past-1b-retailsales/ Page 10: Eaton Centre; Top image from 1985 (City of Toronto Archives) and bottom image from 2020 (Google Maps. Accessed 15 January 2021). Page 11: Yonge-Sheppard Centre (Toronto) Top: Google Maps. Accessed 15 January 2021 Pages 12 & 13: 1969, 1971, and 1992 image source: https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/accountability-operations-customer-service/access-city- information-or-records/city-of-toronto-archives/whats-online/maps/aerial-photographs/); and 2009 and 2020 images are from Google Earth accessed January 2021 Note: Images not listed here belong to the City of Toronto CITY OF TORONTO 2021 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2 1.1 THE GUIDE -

UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Life in the city starts at the centre: a genealogy of the neoliberal city, through four generations of shopping spaces in Toronto Author(s) McElligott, Christopher Publication date 2017 Original citation McElligott, C. 2017. Life in the city starts at the centre: a genealogy of the neoliberal city, through four generations of shopping spaces in Toronto. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2017, Christopher McElligott. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information Restricted to everyone for three years Embargo lift date 2020-10-18T10:43:52Z Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/4914 from Downloaded on 2021-10-10T18:54:49Z Life in the City starts at the Centre A genealogy of the neoliberal city, through four generations of shopping spaces in Toronto Christopher McElligott BA (Hons) MPlan Thesis submitted for PhD programme i n S o c i a l S c i e n c e s , G r a d u a t e Research Education Programme N a t i o n a l U n i v e r s i t y of Ireland, Cork Head of Department: Dr Niamh Hourigan Supervisor: Dr Kieran Keohane Table of Contents List of Images ........................................................................................................... 5 List of Figures .......................................................................................................... 7 Declaration .............................................................................................................. -

Map of Don Mills Middle School

Attachment 1: Submissions Public Meeting, Don Mills Middle School and the location of the Don Mills Civitan Arena Comments received by E-mail December 03, 2013 Dear David, Phillip and Brenda, I hope this mail finds you well. My name is Sinan Madenli and I am a resident of Don Mills, living at 64 Greenland Road (at the corner of Lawrence Ave. East and Greenland Rd.). On (19th September, 2003) we have been informed at the informal Community Informational meeting forced by Councillor Denzel Minnan-Wong that TDSB took a decision to sell “surplus” properties at number of school locations which amongst them is the field at the north of Don Mills Collegiate Institute that belongs to Don Mills Middle Scholl in an “In Camera” meeting. My property is adjacent to the field mentioned above and naturally this action by TDSB will have severe consequences for me and many other neighbours which are in the same position as I am. Regardless of who acquires this property and what kind of development occurs on it , it will have a major impact on us ranging from the decreasing the value of our property, to disturbance of peace and quiet we are enjoying, to tripling the traffic congestion in the area. Furthermore, when this decisions was made in June 9th 2013 meeting, it appears DMMS field was added to the list in a last minute snap decision (unfortunately) with the recommendation of our school trustee Harout Manaugian under the influence of heavy lobbying by DMRI (Terry West), Civitan Club Members and Build Toronto, hoping that to convince the City planners locate the new Civitan Arena at this location. -

Central Don Mills Secondary Plan 24

24 CENTRAL DON MILLS SECONDARY PLAN 24. CENTRAL DON MILLS SECONDARY PLAN The lands affected by the Central Don Mills Secondary Plan are shown on Map 24-1. 1. GENERAL CONCEPT 1.1 Central Don Mills was planned and built in the 1950’s as a self-contained community. A unique development in its time, it became a model for suburban development across Canada. Although Don Mills changed and evolved, basic elements remained. These are: a) four discrete neighbourhoods each historically focused on an elementary school and church, built outside of a ring road (The Donways); b) apartment development within the ring road; c) a central commercial and community centre within The Donways at the southwest corner of Don Mills Road and Lawrence Avenue; d) a local road network in the four neighbourhoods designed to discourage through traffic; e) schools in an open space setting; f) an open space network comprised of parks and walkways that provide pedestrian and cycling links between the neighbourhoods and the community centre; g) a balanced mix of housing forms and tenures, including detached and semi-detached dwellings, townhouses and apartments; h) a sense of scale and consistency in design; i) the arrangement of built form and open spaces in a sympathetic, mutually supportive manner; and j) design and landscaping reflecting the garden city concept. These elements will continue to provide the framework of the Secondary Plan Area as it evolves. 1.2 Background 1.2.1 Don Mills Centre The Don Mills Centre has developed as a commercial area containing a shopping mall, other retail uses, offices, a post office and an arena. -

Sep21 2006 Vol37 No1.Pdf

NEWS September 21. 2006 Solar B, a spacecraft developed by the Japanese Space Agency is set to launch from Uchinoura Space Centre in Japan tomorrow. - www.universetoday.com Gordon hopes government Humber Journalism students have a $2 million home this year will allow polytechnic move Laurie Wilson Hanna, the Dean of Media Studies NEWS REPORTER and Information Technology. The Josh Stem tially, it's a matter of setting Gordon said. technology and structure of the NEWS REPORTER Humber up as a quality brand But when it comes to change, "by A major summer facelift of newsroom is comparable to pro- that people will automatically definition if you think you got it Humber College's newsroom fessional newsrooms. It is If things go according to associate with a good quality edu- perfect you're slipping backwards. brings in new technology, a bold equipped with four state of the art President Gordon's plan, Humber cation, not just in Ontario, but in It's sort of like a treadmill always new design and fresh new atti- high definition capable television could soon undergo another name Canada. Humber will continue to moving forward." tudes. cameras, a new radio and televi- change. be called an institute of technolo- So, it's not that the culture is The $2 million renovation has sion receiver, as well as new Assuming the government until the government decides being redefined, but that an effort gy created a unified headquarters for Macintosh C]5 computers. approves, Humber will evolve to change it, which could take must be made to uphold the same the print and broadcast sections of Ciuinane said the renovations will from being called an Institute of standards under our new leader- some time.