Making Aid Work: Towards Better Development Results Practical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONSOLIDATED REPLY Parliamentary Oversight of Gender Equality

CONSOLIDATED REPLY of the e-Discussion on: Parliamentary Oversight of Gender Equality April 2016 CONSOLIDATED REPLY_iKNOW Politics e-Discussion: Parliamentary Oversight of Gender Equality LAUNCHING MESSAGE Spanish French Arabic Parliaments are key stakeholders in the promotion and achievement of gender equality. Parliamentary oversight processes provide an opportunity to ensure that governments maintain commitments to gender equality. While women parliamentarians have often assumed responsibility for this oversight, many parliaments are taking a more holistic approach by establishing dedicated mechanisms and systematic processes across all policy areas to mainstream the advancement of gender equality. The oversight role of parliamentarians is linked to the very notion of external accountability, the democratic control of the government by the parliament, among other bodies. Since gender equality improves the quality of democracy, the parliamentary oversight of gender equality is a key aspect of modern parliaments and a fundamental contribution for the achievement of sustained democratic practices. Against this backdrop and to contribute to the forthcoming second Global Parliamentary Report on Parliament's power to hold government to account: Realities and perspectives on oversight - a joint publication of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) - iKNOW Politics is moderating an e-Discussion on 'Parliamentary Oversight of Gender Equality'. The e-Discussion runs from 25 January - 28 February 2016 and seeks to highlight the willingness and capacity of parliaments to keep governments accountable on the goal of gender equality and ensure parliamentary oversight is gender-sensitive, as well as the opportunities available to both women and men parliamentarians to engage in oversight. One of the main objectives of this e-Discussion, thus, is to find best practices that will help to strengthen external accountability and the consolidation of sustained democratic practices. -

Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention Against

United Nations CAC/COSP/2009/INF.2 Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations 13 November 2009 Convention against Corruption English/French/Spanish Third Session Doha, 9 to 13 November 2009 FINAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS States Parties Afghanistan Basir Ahmed ORIA, Advisor, High Office of Oversight Mohammad Qaseem LUDIN, Policy Advisor to the Senior Management Albania Oerd BYLYKABSHI, Chef de la Délégation Helena PAPA Adriatik LLALLA Algeria Taous FEROUKHI, Ambassadeur, Représentant Permanent, La Mission Permanente de la République Algérienne Démocratique et Populaire auprès de l'Office des Nations Unies et des Organisations Internationales à Vienne, Chef de la Délégation Nabil HATTALI, Chargé de Mission, Ministère des Affaires Étrangères Tahar ABDELLAOUI, Directeur de la Coopération Juridique et Judiciaire, Ministère de la Justice Mokhtar LAKHDARI, Directeur des Affaires Pénales et des Grâces, Ministère de la Justice Aziz AL AFANI, Directeur de la Police Judiciaire, Ministère de l'Intérieur Ahmed BOUBEGRA Nacer-Eddine MAROUK, Docteur, Conseiller auprès du Ministère de la Justice Hasen SEFSAF Abdul Majid AMGHAR This document has not been edited and is being posted on the web for information purposes only. CAC/COSP/2009/INF.2 Angola Fidelino Loy DE JESUS FIGUEIREDO, Ambassador, Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Mission of the Republic of Angola to the United Nations (Vienna), Chairperson, African Group Pascoal António JOAQUIM, Deputy General Attorney Jacinto Rangel Lopes CORDEIRO NETO, Minister Counselor, Advisor to -

Global Parliamentary Report: Global Parliamentary Report: the Changing Naturerepresentation of Parliamentary IPU - UNDP

GLOBAL PARLIAMENTARY Better parliaments, stronger democracies. REPORT The changing nature of parliamentary representation Global Parliamentary Report: The changing nature of parliamentary changing nature representation The Global Parliamentary Report: IPU - UNDP. 2012 IPU - UNDP. Inter-Parliamentary Union ❙ United Nations Development Programme Lead author: Greg Power Assistant to the lead author: Rebecca A. Shoot Translation: Sega Ndoye (French), Peritos Traductores, S.C. (Spanish), Houria Qissi (Arabic) Cover design and layout: Kimberly Koserowski, First Kiss Creative LLC Printing: Phoenix Design Aid A/S Sales: United Nations Publications Photo credits: Cover Illustration: James Smith, pg. 9: UN Photo/Albert Gonzalez Farran, pg. 24: UK Parliament copyright, pg. 42: UNDP/Afghanistan, pg. 58: Fabián Rivadeneyra, pg. 72: Assemblée nationale 2012 April 2012 Copyright © UNDP and IPU All rights reserved Printed in Denmark Sales No.: E.11.III.B.19 ISBN: 978-92-1-126317-6 (UNDP) ISBN: 978-92-9142-532-7 (IPU) eISBN: 978-92-1-054990-5 Inter-Parliamentary Union United Nations Development Programme 5 chemin du Pommier Democratic Governance Group CH-1218 Le Grand-Saconnex Bureau for Development Policy Geneva, Switzerland 304 East 45th Street, 10th Floor Telephone: +41 22 919 41 50 New York, NY, 10017, USA Fax: +41 22 919 41 60 Telephone: +1 (212) 906 5000 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +1 (212) 906 5857 www.ipu.org www.undp.org This publication results from the partnership between UNDP and IPU. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, UNDP or IPU. Better parliaments, stronger democracies. GLOBAL PARLIAMENTARY REPORT The changing nature of parliamentary representation Inter-Parliamentary Union ❙ United Nations Development Programme April 2012 ADVISORY BOARD ■ Mr. -

Standards for Democratic Parliaments by Kevin Deveaux

Standards for Democratic Parliaments By Kevin Deveaux Kevin Deveaux, UNDP he Necessity of Standards or Benchmarks Parliamentary Develop- ment Policy Adviser, has Every institution should be able to measure been Member of the Nova its progress over time, to ensure it is Scotia House of AssemBly improving its capacity to meet its mandate from 1998 to 2007. and to continuously review its efforts to In order to promote become a better institution. Parliaments are no exception. In transparent accountaBle many countries, parliaments are under-resourced and not parliaments, Kevin started to work with the NDI in Kosovo, CamBodia and able to fully conduct the key constitutional functions the Middle East. Then in 2007, he started to work for mandated to them, such as passing quality legislation, UNDP as Senior Technical Adviser to the National scrutinizing the actions of the government and conducting an AssemBly of Vietnam and, in 2008, was made the UNDP ongoing dialogue with citizens. In other countries, Parliamentary Development Policy Adviser, at gloBal parliaments and parliamentarians are unable to maintain a level. stable institution as a result of fragility or conflict within the state. And yet other countries have focused primarily on A Work in Progress ensuring free and fair elections but have not considered the need for strong democratic institutions once the elections Based on previous standards-based approaches in the fields have concluded. of human rights and elections, the global parliamentary development community commenced working on standards For these reasons and others, parliaments must have a set of or benchmarks for democratic parliaments in 2003. -

Theparliamentarian

100th year of publishing TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2019 | Volume 100 | Issue One | Price £14 Women and Parliament: 30th anniversary of the Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians PAGES 20-69 PLUS Commonwealth Women Towards safe work Importance of education Male Parliamentarians in politics: Progress on environments in to increase women’s as ‘agents of change’ global change Parliaments political participation PAGE 23 PAGE 36 PAGE 44 PAGE 60 CPA Masterclasses STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, Online video Masterclasses build an informed promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of parliamentary community across the Commonwealth good governance, and implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. and promote peer-to-peer learning Calendar of Forthcoming Events Confirmed as of 25 February 2019 CPA Masterclasses are ‘bite sized’ video briefings and analyses of critical policy areas 2019 and parliamentary procedural matters by renowned experts that can be accessed by March the CPA’s membership of Members of Parliament and parliamentary staff across the Friday 8 March International Women’s Day 2019 Commonwealth ‘on demand’ to support their work. Monday 11 March Commonwealth Day 2019 – ‘A Connected Commonwealth’, CPA HQ and all CPA Branches April 11 to 15 April Mid-Year meeting of the CPA Executive Committee, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada May 1 to 2 May CPA Parliamentary Strengthening Seminar for the Parliament of Bermuda, Hamilton, Bermuda 19 to 22 May 48th CPA British Islands and Mediterranean Regional Conference, St Peter Port, Guernsey July 12 to 19 July 44th Annual Conference of the CPA Caribbean, Americas and Atlantic Region, Trinidad and Tobago September 22 to 29 September 64th Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference (CPC), Kampala, Uganda – including 37th CPA Small Branches Conference and 6th triennial Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians (CWP) Conference. -

Regional Seminar Report

Regional Seminar Report Regional Seminar Report Strengthening the Role of Parliaments in Crisis Prevention and Recovery in the Arab States Region 2- 4 November 2010, Amman, Jordan December 2010 Dec 2010 Page 1 Regional Seminar Report Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations 3 Executive Summary 4 Workshop Rationale and Objectives 5 Main Elements of Discussion 8 Introductory Session Session 1: Parliaments and Conciliation……………………………………………………………………….…….08 Session 2: Parliaments and Arab Regional Organizations in Conflict Prevention………….……11 Session 3: Gender Sensitivities and Conflict………………………………………………………………………14 Session 4: Working Groups…………………………………………………………………………………………….….16 Session 5: National Parliaments and conflict prevention and recovery efforts - Perspectives of national organizations working on parliamentary development…………….…..18 Session 6: International organizations working on parliamentary development and crisis prevention: Success stories and lessons learned………………………………20 Session 7: Presentation of UNDP’s new project on parliamentary development and crisis prevention and the draft self-assessment tool on parliamentary performance and crisis prevention and recovery……………………………………………..24 Sessions 8 Round tables: Possible solutions, opportunities and workplan at & 9: the regional and national levels to collectively improve parliamentary performance in crisis prevention and recovery issues in the Arab States region…………………………………………………………………………26 Session 10: Presentation of round tables discussions…………………………………………………………26 Conclusions -

Core 1..48 Committee

House of Commons CANADA Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development FAAE Ï NUMBER 038 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Tuesday, January 30, 2007 Chair Mr. Kevin Sorenson Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1 Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development Tuesday, January 30, 2007 Ï (0905) Mr. Goodridge, I understand you have a presentation and that [English] afterwards all members of your group will be open to questions from the committee. The Chair (Mr. Kevin Sorenson (Crowfoot, CPC)): Good morning, everyone. This is meeting number 38 of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development, on Welcome. Tuesday, January 30, 2007. Mr. William H. Goodridge (Member, International Develop- I want to take this opportunity to welcome everyone back. I hope ment Committee, Canadian Bar Association): Thank you, Mr. you all had a merry Christmas and enjoyed spending the holiday Chair, and thank you, honourable members. time with family and friends. I want to say a special welcome back to Madame Lalonde, who The Canadian Bar Association is happy to have this opportunity has had a long— today to share our perspective on Canada's support for democratic Some hon. members: Hear, hear! development abroad. I came here today from St. John's, Newfound- land. I'm a member of the international development committee, but The Chair: I can assure you our prayers and our best wishes have I came here specifically to make this presentation before the been with you, Madame. -

Written Submission House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs

Deveaux International Governance Consultants Inc. 2180 Shore Rd., Eastern Passage, NS B3G 1H6 Canada +1(902)403-4325 Written Submission House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs Kevin Deveaux1 Deveaux International Governance Consultants Inc. Background The House of Commons has tasked the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs with the task of reviewing the current Standing Orders to reflect on what amendments are required to enable the Parliament to function effectively during a protracted emergency, such as the current COVID-19 pandemic. The focus of this review is on the immediate needs of the House to adjust to the current emergency situation and the rules that may be in place if and when another similar emergency commences. The Committee has requested submissions from academics and legal and technical experts with regard to their perspective on the issue currently before the Committee. This submission is based on the experience of the author as a former MLA, House Leader, Deputy Speaker and as a global adviser to parliaments. Core Principles for Emergency Parliament Sittings To start, it is crucial that any revised rules and Standing Orders reflect a set of principles that are based on the status and importance of Parliament as an integral component of our democratic system and the need to ensure that during an emergency situation the principles upon which our democracy are based are not jettisoned. It is submitted that any list of core principles must reflect: • Parliamentary Supremacy: An active Parliament during an emergency is not an option, it is a necessity. To avoid future debates about if and when the House will be called back, it is important that the institution is recognized as supreme, as is reflected in our Constitution, and can automatically initiate its own proceedings. -

Empoderando a Las Mujeres Para El Fortalecimiento De Los Partidos Políticos

empoderando a las mUjeres para el fortalecimiento de los partidos políticos Una gUía de bUenas prácticas para promover la participación política de las mUjeres programa de naciones Unidas para el desarrollo instituto nacional demócrata empoderando a las mUjeres para el fortalecimiento de los partidos políticos Una gUía de bUenas prácticas para promover la participación política de las mUjeres empoderando a las mUjeres para el fortalecimiento de los partidos políticos Una gUía de bUenas prácticas para promover la participación política de las mUjeres AutorA AgrAdecimientos Principal El PNUD y el NDI desean expresar su agradecimiento a todos los que han contri- julie ballington buido a la realización de este documento. colAborAdores Esta publicación fue originalmente concebida por Winnie Byanyima, Randi Davis y Autores de y Kristin Haffert y sus inestimables aportaciones ayudaron a hacerla realidad. cAsos Prácticos randi davis Los casos prácticos originales y los textos resumen que nutrieron este documento mireya reith fueron desarrollados y/o investigados por Lincoln Mitchell, con contribuciones lincoln mitchell de Mireya Reith, Elizabeth Powley, Carole Njoki y Marilyn Achiron. Julie Ballington carole njoki ha guiado la concreción de la publicación. alyson Kozma Aportaron amablemente sus opiniones y comentarios Suki Beavers, Shari Bryan, elizabeth powley Drude Dahlerup, Randi Davis, Kevin Deveaux, Aleida Ferreyra, Simon Alexis Finley, Geraldine Fraser-Moleketi, Kristin Haffert, Oren Ipp, Linda Maguire, editorA de coPiA Susan Markham, Mireya Reith, Carmina Sanchis Ruescas, Kristen Sample, Louise manuela popovici Sperl y Ken Wollack. trAductorA Debemos agradecer también al gran número de personas entrevistadas el mara Kolesas tiempo que nos han dedicado y los conocimientos que han aportado al desa- rrollo de los casos prácticos, sin olvidar a todo el personal local y regional del diseño IDN que ayudó a facilitar la investigación de campo. -

Supporting Democratic Transition in Tunisia

JULY 2011 RESULTS SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC Technical Support was provided to draft new laws TRANSITION IN TUNISIA: for political parties and NGOs. Participative process afforded representatives of political parties and NGOs the opportunity to Since the departure of former President Ben Ali in January provide inputs and recommendations for final 2011, Tunisia has been witnessing a phase of dramatic version of both laws. transition to democracy involving a complete overhaul of 45 women politicians were trained to conduct its political system. UNDP has immediately refocused its successful electoral campaigns and to train others work in Tunisia to support key institutions, processes and within their political parties. stakeholders that can have a significant impact in assuring the steady transition to democracy – including support to Representatives of 50 political parties benefited the constitutional process, political parties, and women’s from Knowledge exchange and comparative political participation. experiences on constitutional processes in Through its Global Programme for Parliamentary transitions - with special focus on south-south Strengthening (a joint effort of the Bureau for exchange (South Africa and Latin America Development Policy, the Bureau for Crisis Prevention and experiences). Recovery) and UNDP Tunisia, UNDP provided support to more than 50 political parties, between April and July 2011. The support focused on strengthening capacities, knowledge and skills of politicians and other stakeholders Participants received technical information needed to (technocrats, civil society members…) and affording them support the finalization of the draft law on political an opportunity to work together and agree on best means parties, including best practices and case studies, mainly to ensuring a peaceful, democratic and a more inclusive from France and East Europe. -

Management Professional Development Online Program

PARLIAMENTARY MANAGEMENT PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT ONLINE PROGRAM LEARN MORE AND REGISTER AT: McGILL.CA/SCS-PARLIAMENT Parliaments are a critical component of a country’s governance system. Typically, they oversee the executive arm of the government, represent the electorate, and formulate and enact legislation. To perform these roles, parliaments need to have strong staff development programs to ensure effective, proactive, and responsive personnel. Building the capacity of staff ensures that the demands and needs of all members of the legislature are met, and helps sustain parliamentary institutions for the challenges of tomorrow. At a time when public expectation for improved democracy is on the rise and that the executive power is still weakening the structure of parliamentary governance in many countries, it is more important than ever to build stronger parliamentary workforces. McGill University’s School of Continuing Studies, in collaboration with the World Bank and other international partners, developed a curriculum based on the findings of the capacity enhancement review conducted in 150 legislatures of the Commonwealth and La Francophonie. A focus group of senior parliamentary staff from Africa, Asia, Australasia, Europe, and North America analyzed the data and formulated recommendations to structure a comprehensive program for parliamentary staff that would address international, national, and regional standards, while acknowledging local customs, and historical realities. The result is a Professional Development Certificate program in Parliamentary Management. This non-credit professional program consists of six expert-moderated online courses, each involving live online sessions, pre-recorded videos, and moderated online discussion forums. To reinforce learning, personal one-on-one professional mentoring complements the courses. -

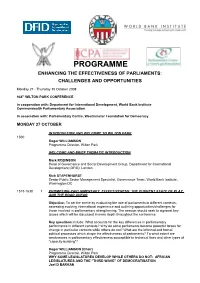

Programme Enhancing the Effectiveness of Parliaments: Challenges and Opportunities

PROGRAMME ENHANCING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PARLIAMENTS: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Monday 27 - Thursday 30 October 2008 934th WILTON PARK CONFERENCE in cooperation with: Department for International Development, World Bank Institute Commonwealth Parliamentary Association In association with: Parliamentary Centre, Westminster Foundation for Democracy MONDAY 27 OCTOBER INTRODUCTION AND WELCOME TO WILTON PARK 1500 Roger WILLIAMSON Programme Director, Wilton Park WELCOME AND BRIEF THEMATIC INTRODUCTION Mark ROBINSON Head of Governance and Social Development Group, Department for International Development (DFID), London Rick STAPENHURST Senior Public Sector Management Specialist, Governance Team, World Bank Institute, Washington DC 1515-1630 1 PROMOTING PARLIAMENTARY EFFECTIVENESS; THE CURRENT STATE OF PLAY AND THE ROAD AHEAD Objective: To set the scene by evaluating the role of parliaments in different contexts, assessing evolving international experience and outlining opportunities/challenges for those involved in parliamentary strengthening. The session should seek to signpost key issues which will be discussed in more depth throughout the conference. Key questions include: What accounts for the key differences in parliamentary performance in different contexts? Why do some parliaments become powerful forces for change in particular contexts while others do not? What are the informal and formal political processes which shape the effectiveness of parliaments? To what extent are weaknesses in parliamentary effectiveness susceptible to technical