ENHANCING YOUTH POLITICAL PARTICIPATION Throughout the ELECTORAL CYCLE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submission to OHCHR Report on Youth and Human Rights in Accordance with Human Rights Council Resolution 35/14

Submission to OHCHR report on Youth and Human Rights in accordance with Human Rights Council Resolution 35/14 I. BACKGROUND IIMA - Istituto Internazionale Maria Ausiliatrice is an international NGO in special consultative status with the Economic and Social Council. IIMA is present in 95 countries where it provides education to children, adolescents, and youth to build up strategies for youth empowerment and participation worldwide. VIDES International - International Volunteerism Organization for Women, Education, and Development is an NGO in special consultative status with the Economic and Social Council, which works in 44 countries worldwide. It was founded in 1987 to promote youth volunteer service at the local and international levels for ensuring human rights, development, and democracy. Through its network of young volunteers worldwide, VIDES promotes best practices on active citizenship among youth. Already for several years, IIMA and VIDES have been working for the empowerment of young people worldwide, not only by reporting existing protection gaps in the implementation of human rights with regard to youth but also by greatly valuing the crucial role of youth in the promotion of human rights for society at large. Accordingly, both NGOs have been active in calling the attention of the Human Rights Council and other UN human rights bodies on the specific situation of youth in order to ensure that the rights of youth are placed high on the list of priorities.1 The present joint contribution intends to respond to the call for inputs launched by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in the framework of the preparation of a detailed study on Youth and Human Rights, as requested by Human Rights Council Resolution 35/14 (June 2017). -

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited Richard G. Medlin Stetson University This article reviews recent research on homeschooled children’s socialization. The research indicates that homeschooling parents expect their children to respect and get along with people of diverse backgrounds, provide their children with a variety of social opportunities outside the family, and believe their children’s social skills are at least as good as those of other children. What homeschooled children think about their own social skills is less clear. Compared to children attending conventional schools, however, research suggest that they have higher quality friendships and better relationships with their parents and other adults. They are happy, optimistic, and satisfied with their lives. Their moral reasoning is at least as advanced as that of other children, and they may be more likely to act unselfishly. As adolescents, they have a strong sense of social responsibility and exhibit less emotional turmoil and problem behaviors than their peers. Those who go on to college are socially involved and open to new experiences. Adults who were homeschooled as children are civically engaged and functioning competently in every way measured so far. An alarmist view of homeschooling, therefore, is not supported by empirical research. It is suggested that future studies focus not on outcomes of socialization but on the process itself. Homeschooling, once considered a fringe movement, is now widely seen as “an acceptable alternative to conventional schooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90). This “normalization of homeschooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90) has prompted scholars to announce: “Homeschooling goes mainstream” (Gaither, 2009, p. 11) and “Homeschooling comes of age” (Lines, 2000, p. -

CONSOLIDATED REPLY Parliamentary Oversight of Gender Equality

CONSOLIDATED REPLY of the e-Discussion on: Parliamentary Oversight of Gender Equality April 2016 CONSOLIDATED REPLY_iKNOW Politics e-Discussion: Parliamentary Oversight of Gender Equality LAUNCHING MESSAGE Spanish French Arabic Parliaments are key stakeholders in the promotion and achievement of gender equality. Parliamentary oversight processes provide an opportunity to ensure that governments maintain commitments to gender equality. While women parliamentarians have often assumed responsibility for this oversight, many parliaments are taking a more holistic approach by establishing dedicated mechanisms and systematic processes across all policy areas to mainstream the advancement of gender equality. The oversight role of parliamentarians is linked to the very notion of external accountability, the democratic control of the government by the parliament, among other bodies. Since gender equality improves the quality of democracy, the parliamentary oversight of gender equality is a key aspect of modern parliaments and a fundamental contribution for the achievement of sustained democratic practices. Against this backdrop and to contribute to the forthcoming second Global Parliamentary Report on Parliament's power to hold government to account: Realities and perspectives on oversight - a joint publication of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) - iKNOW Politics is moderating an e-Discussion on 'Parliamentary Oversight of Gender Equality'. The e-Discussion runs from 25 January - 28 February 2016 and seeks to highlight the willingness and capacity of parliaments to keep governments accountable on the goal of gender equality and ensure parliamentary oversight is gender-sensitive, as well as the opportunities available to both women and men parliamentarians to engage in oversight. One of the main objectives of this e-Discussion, thus, is to find best practices that will help to strengthen external accountability and the consolidation of sustained democratic practices. -

Enhancing Youth-Elder Collaboration in Governance in Africa

Discussion Paper ENHANCING YOUTH-ELDER COLLABORATION IN GOVERNANCE IN AFRICA The Mandela Institute for Development Studies Youth Dialogue 7-8 August 2015 Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe Authored and presented by Ms. Ify Ogo PhD Candidate, Maastricht University MINDS Annual African Youth Dialogue 2015 Discussion Paper ABSTRACT Youth constitute the majority of the population on the African continent. This paper explores the convergence of traditional (African Tradition) and modern ways of social engagement in political governance interactions. It discusses the imperative for youth participation in governance, as well as the challenges and opportunities for dialogue between youth and elders in governance systems. In the first chapter, the paper discusses cultural norms which have prevented the development of collaboration between youth and elders, as well as the consequences of constricted relationships, for example the entrenchment of elders as leaders. The chapter concludes with proffering strategies for reform, including a redefined understanding of governance, performance based evaluation criteria for leaders and the strengthening of institutions. Through case studies, the second chapter of this paper outlines key issues the youth face in collaborating with elders in governance. The case studies present youth who have attempted to drive development agenda within government, as well as those who have successfully influenced political decision making and action. This chapter highlights some of the strategies the youth who have successfully influenced elders in political decision making have employed, in order to gain influence and collaborate with the elders. 2 MINDS Annual African Youth Dialogue 2015 Discussion Paper CONTENTS Abstract 2 Chapter One 4 1.1. The Imperative for Youth-Elder Collaboration in Governance 4 1.2. -

Youth Engagement and Empowerment Report

Youth Engagement and Empowerment In Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia Agenda Youth Engagement and Empowerment In Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia November 2018 version TABLE OF CONTENTS │ 3 Table of contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Notes .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1. Towards national integrated youth strategies ................................................................. 7 Jordan ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Morocco ............................................................................................................................................... 9 Tunisia ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Good practices from OECD countries ............................................................................................... 11 Chapter 2. Strengthening the formal body responsible for co-ordinating youth policy and inter-ministerial co-ordination ........................................................................................................... 13 Jordan ................................................................................................................................................ -

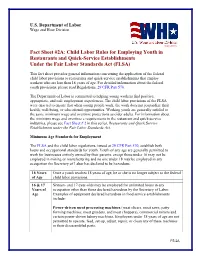

Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division (July 2010) Fact Sheet #2A: Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) This fact sheet provides general information concerning the application of the federal child labor provisions to restaurants and quick-service establishments that employ workers who are less than 18 years of age. For detailed information about the federal youth provisions, please read Regulations, 29 CFR Part 570. The Department of Labor is committed to helping young workers find positive, appropriate, and safe employment experiences. The child labor provisions of the FLSA were enacted to ensure that when young people work, the work does not jeopardize their health, well-being, or educational opportunities. Working youth are generally entitled to the same minimum wage and overtime protections as older adults. For information about the minimum wage and overtime e requirements in the restaurant and quick-service industries, please see Fact Sheet # 2 in this series, Restaurants and Quick Service Establishment under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Minimum Age Standards for Employment The FLSA and the child labor regulations, issued at 29 CFR Part 570, establish both hours and occupational standards for youth. Youth of any age are generally permitted to work for businesses entirely owned by their parents, except those under 16 may not be employed in mining or manufacturing and no one under 18 may be employed in any occupation the Secretary of Labor has declared to be hazardous. 18 Years Once a youth reaches 18 years of age, he or she is no longer subject to the federal of Age child labor provisions. -

CFCI Child and Youth Participation, Options for Action

©City of Regensburg Child Friendly Cities Initiative Child and Youth Participation – Options for Action April 2019 Child and Youth Participation - Options for Action 1 Aknowledgements This brief, issued by UNICEF, was authored by Gerison Lansdown with inputs from Louise Thivant, Marija de Wijn, Reetta Mikkola and Fabio Friscia. All rights to this publication remain with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Any part of the report may be freely reproduced with the appropriate acknowledgement. © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) April 2019 Child and Youth Participation - Options for Action 2 Child and Youth Participation – Options for Action April 2019 Child and Youth Participation - Options for Action 3 Contents 1. Introduction and rationale...................................................................................... 5 2. Understanding meaninful participation................................................................ 6 2.1 Different levels of participation 4 2.2 Inclusive participation 8 3. Participation of children and young people throughout the CFCI cycle............. 10 3.1 Establishing the CFCI 11 3.2 Child rights situation analysis 12 3.3 The CFCI Action Plan and budget 14 3.4 Implementation 16 3.5 Evaluation and review 20 3.6 CFCI recognition event 22 Resources................................................................................................................. 23 Annex I: Child Friendly Cities Initiative Safeguarding Guidance......................... 24 Child and Youth Participation - Options for Action 4 1 Introduction and rationale A Child Friendly City is a city or community where the local government is committed to implementing the Convention on the Rights of the Child by translating the rights into practical, meaningful and measurable results for children. It is a city or community where the needs, priorities and voices of children are an integral part of public policies, programmes and decision making. -

Developing and Validating a Scale to Measure Youth Voice Jessica Bartak University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses, Dissertations, & Student Scholarship: Agricultural Leadership, Education & Agricultural Leadership, Education & Communication Department Communication Department 12-2018 Developing and Validating a Scale to Measure Youth Voice Jessica Bartak University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/aglecdiss Part of the Leadership Studies Commons Bartak, Jessica, "Developing and Validating a Scale to Measure Youth Voice" (2018). Theses, Dissertations, & Student Scholarship: Agricultural Leadership, Education & Communication Department. 108. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/aglecdiss/108 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Agricultural Leadership, Education & Communication Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, & Student Scholarship: Agricultural Leadership, Education & Communication Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DEVELOPING AND VALIDATING A SCALE TO MEASURE YOUTH VOICE By Jessica E. Bartak A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Leadership Education Under the Supervision of Professor L.J. McElravy Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2018 DEVELOPING AND VALIDATING A SCALE TO MEASURE YOUTH VOICE Jessica E. Bartak, M.S. University of Nebraska, 2018 Advisor: L.J. McElravy The purpose of this study is to develop and validate a scale to measure the level of engagement of youth in their community or organization using the construct of youth voice. Youth voice consists of three levels: being heard, collaborating with adults, and building leadership capacity. -

Download Issue

YOUTH &POLICY No. 116 MAY 2017 Youth & Policy: The final issue? Towards a new format Editorial Group Paula Connaughton, Ruth Gilchrist, Tracey Hodgson, Tony Jeffs, Mark Smith, Jean Spence, Naomi Thompson, Tania de St Croix, Aniela Wenham, Tom Wylie. Associate Editors Priscilla Alderson, Institute of Education, London Sally Baker, The Open University Simon Bradford, Brunel University Judith Bessant, RMIT University, Australia Lesley Buckland, YMCA George Williams College Bob Coles, University of York John Holmes, Newman College, Birmingham Sue Mansfield, University of Dundee Gill Millar, South West Regional Youth Work Adviser Susan Morgan, University of Ulster Jon Ord, University College of St Mark and St John Jenny Pearce, University of Bedfordshire John Pitts, University of Bedfordshire Keith Popple, London South Bank University John Rose, Consultant Kalbir Shukra, Goldsmiths University Tony Taylor, IDYW Joyce Walker, University of Minnesota, USA Anna Whalen, Freelance Consultant Published by Youth & Policy, ‘Burnbrae’, Black Lane, Blaydon Burn, Blaydon on Tyne NE21 6DX. www.youthandpolicy.org Copyright: Youth & Policy The views expressed in the journal remain those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editorial Group. Whilst every effort is made to check factual information, the Editorial Group is not responsible for errors in the material published in the journal. ii Youth & Policy No. 116 May 2017 About Youth & Policy Youth & Policy Journal was founded in 1982 to offer a critical space for the discussion of youth policy and youth work theory and practice. The editorial group have subsequently expanded activities to include the organisation of related conferences, research and book publication. Regular activities include the bi- annual ‘History of Community and Youth Work’ and the ‘Thinking Seriously’ conferences. -

Tunisia, Breaking the Barriers to Youth Inclusion

TUNISIA Breaking the Barriers to Youth Inclusion # 13235B # 39A9DC # 622181 # E41270 # DFDB00 TUNISIA Breaking the Barriers to Youth Inclusion # 13235B # 39A9DC # 622181 # E41270 # DFDB00 Copyright © 2014 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank Group 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433, USA All rights reserved Report No. 89233-TN Tunisia ESW: Breaking the Barriers to Youth Inclusion P120911–ESW Disclaimer The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Di- rectors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank, Tunisia, and governments represented do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or accep- tance of such boundaries. The present report is based mostly on the quantitative analysis of the Tunisia Household Surveys on Youth in Rural Areas (THSYUA 2012) and its companion, the Tunisia Household Surveys on Youth in Rural Areas (THSYRA 2012). The Tunisia National Youth Observatory (ONJ) is not responsible for the data and figures presented in this report. Electronic copies in Arabic and English can be downloaded free of charge upon request to the World Bank. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, www.copyright.com. -

Youth Participation in Electoral Processes Handbook for Electoral Management Bodies

Youth Participation in Electoral Processes Handbook for Electoral Management Bodies FIRST EDITION: March 2017 With support of: European Commission United Nations Development Programme Global Project Joint Task Force on Electoral Assistance for Electoral Cycle Support II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Lead authors Ruth Beeckmans Manuela Matzinger Co-autors/editors Gianpiero Catozzi Blandine Cupidon Dan Malinovich Comments and feedback Mais Al-Atiat Julie Ballington Maurizio Cacucci Hanna Cody Kundan Das Shrestha Andrés Del Castillo Aleida Ferreyra Simon Alexis Finley Beniam Gebrezghi Najia Hashemee Regev Ben Jacob Fernanda Lopes Abreu Niall McCann Rose Lynn Mutayiza Chris Murgatroyd Noëlla Richard Hugo Salamanca Kacic Jana Schuhmann Dieudonne Tshiyoyo Rana Taher Njoya Tikum Sébastien Vauzelle Mohammed Yahya Lea ZoriĆ Copyeditor Jeff Hoover Graphic desiger Adelaida Contreras Solis Disclaimer This publication is made possible thanks to the support of the UNDP Nepal Electoral Support Project (ESP), generously funded by the European Union, Norway, the United Kingdom and Denmark. The information and views set out in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the UN or any of the donors. The recommendations expressed do not necessarily represent an official UN policy on electoral or other matters as outlined in the UN Policy Directives or any other documents. Decision to adopt any recommendations and/or suggestions presented in this publication are a sovereign matter for individual states. Youth -

Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention Against

United Nations CAC/COSP/2009/INF.2 Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations 13 November 2009 Convention against Corruption English/French/Spanish Third Session Doha, 9 to 13 November 2009 FINAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS States Parties Afghanistan Basir Ahmed ORIA, Advisor, High Office of Oversight Mohammad Qaseem LUDIN, Policy Advisor to the Senior Management Albania Oerd BYLYKABSHI, Chef de la Délégation Helena PAPA Adriatik LLALLA Algeria Taous FEROUKHI, Ambassadeur, Représentant Permanent, La Mission Permanente de la République Algérienne Démocratique et Populaire auprès de l'Office des Nations Unies et des Organisations Internationales à Vienne, Chef de la Délégation Nabil HATTALI, Chargé de Mission, Ministère des Affaires Étrangères Tahar ABDELLAOUI, Directeur de la Coopération Juridique et Judiciaire, Ministère de la Justice Mokhtar LAKHDARI, Directeur des Affaires Pénales et des Grâces, Ministère de la Justice Aziz AL AFANI, Directeur de la Police Judiciaire, Ministère de l'Intérieur Ahmed BOUBEGRA Nacer-Eddine MAROUK, Docteur, Conseiller auprès du Ministère de la Justice Hasen SEFSAF Abdul Majid AMGHAR This document has not been edited and is being posted on the web for information purposes only. CAC/COSP/2009/INF.2 Angola Fidelino Loy DE JESUS FIGUEIREDO, Ambassador, Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Mission of the Republic of Angola to the United Nations (Vienna), Chairperson, African Group Pascoal António JOAQUIM, Deputy General Attorney Jacinto Rangel Lopes CORDEIRO NETO, Minister Counselor, Advisor to