Road to Mission: the Third Fork in the Road Could the Road Less Traveled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Grocery Stores and Restaurants.Pdf

Next door to Newton is the town of Waltham, where a five minute drive from campus will bring you to Waltham’s busy and international Moody Street. Moody Street is home to many international restaurants and grocery stores. Hopefully you can find some familiar foods from home or at least the ingredients to cook a meal for yourself. You may find that the food served in these restaurants is slightly Americanized, but hopefully you’ll still be able to enjoy the familiar smells and tastes of home. A number of these restaurants also have food delivery to your room. You can call the restaurant and ask if they deliver. Be prepared with your address to tell the driver where to bring the food! Greek International Food Market The Reliable Market 5204 Washington St, West Roxbury, MA 02132 45 Union Square, Somerville MA, 02143 9:00AM - 8:00PM (Bus 85) (617) 553-8038 Japanese and Korean groceries at good prices. greekintlmarket.com Mon – Wed 9:30AM - 9:00PM farm-grill.com Thu – Fri 9:30AM - 10:00PM specialtyfoodimports.com Sat 9:00 AM - 10:00 PM Sun 9:00 AM - 9:00 PM Hong Kong Market (617) 623-9620 1095 Commonwealth Ave, Boston MA, (Packard's Corner, Green Line B) Ebisuya Japanese Market Enormous supermarket stocked with imported foods 65 Riverside Ave, Medford MA, 02155 from all over Asia, plus fresh meats & seafood. (Bus 96 to Medford Square) Mon-Thu, Sat-Sun 9AM – 9PM Very fresh sushi-grade fish here. Fri 9AM – 10PM Open 10:00 AM - 8:00 PM (781) 391-0012 C Mart ebisuyamarket.com 109 Lincoln St, Boston MA 02111 (Chinatown Station, Orange Line) The Shops at Porter Square This Asian supermarket carries an extensive University Hall, 1815 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge selection of produce, seafood, meat & imported foods. -

Mothers Across Borders: a Transnational Analysis Of

MOTHERS ACROSS BORDERS: A TRANSNATIONAL ANALYSIS OF PARENTING BETWEEN INDIAN MOTHERS IN EDISON AND KOLKATA by MADHURIMA DAS A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Sociology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Madhurima Das Title: Mothers Across Borders: A Transnational Analysis of Parenting Between Indian Mothers in Edison and Kolkata This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Sociology by: Eileen Otis Chairperson Ellen Scott Core Member Jill Harrison Core Member Arafaat Valiani Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Madhurima Das iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Madhurima Das Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology June 2017 Title: Mothers Across Borders: A Transnational Analysis of Parenting Between Indian Mothers in Edison and Kolkata. This dissertation addresses the central question- How are parenting methodologies across the sending and receiving nations shaped by larger macro forces embedded in economy and labor market forces? In order to answer this key question this project analyzes interviews with 59 middle-class mothers in Edison, New Jersey and Kolkata, India. This project contributes to the larger scope of immigration and transnational studies while placing them at the cross section of globalization of economy, labor market and education. The first chapter examines extensively the schooling systems in Edison and Kolkata and the ways it shapes parenting methods in these two locations. -

Little India Guide Discover a Cultural Experience Beyond Words a Unique Blend of the Best of the Modern World and Rich Cultures to Deliver Enriching

Little India Guide Discover a Cultural Experience beyond words A unique blend of the best of the modern world and rich cultures to deliver enriching experiences CONTENTS Sights of Little India 5 Hallmarks of Little India 13 Souvenirs of Little India 16 Flavours of Little India 20 Nightlife in Little India 26 Festivals in Little India 29 Recommended guided tours 31 MRT and LRT System Map 32 Essential Visitors Information 34 Singapore Tourism Board 36 International Offices Places of Interest 38 Singapore Visitors Centres 42 Sights of Little India Be awed by intricate visages like elaborate gopuram, sculptured tower with carvings derived from Hindu mythology, as well as rare sights like Singapore’s last traditional spice grinder. Get ready for a titillating experience in Little India. Places of worship Sri Veeramakaliamman Temple 141 Serangoon Road Built in 1885, this historical temple is dedicated to Kali, the Goddess of Power and the ferocious incarnation of Lord Shiva’s wife. Veeramakaliamman means ‘Kali the Courageous’. True to its name, this temple courageously offered refuge to many during World War II. Devotees entering the temple ring the many bells on its door, hoping to have their requests granted. At the main shrine is a multi-armed statue of Kali, flanked by her sons Ganesha the Elephant God (also known as the Remover of Obstacles), and Murugan the God of War, often depicted riding a peacock. LIFE IN LITTLE INDIA When to visit: This intriguing enclave of Indian culture and tradition began 5.30am - 9.00pm daily (except 12.30pm - 4.00pm) as brick kilns in the 1820s. -

THE DIASPORA a Symposium On

THE DIASPORA a symposium on Indian-Americans and the motherland symposium participants THE PROBLEM A short statement of the issues involved LABOUR AND LONGING Vinay Lal, Associate Professor of History, University of California, Los Angeles DUSRA HINDUSTAN Vijay Prashad, International Studies Program, Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut FIRM OPINIONS, INFIRM FACTS Devesh Kapur, Associate Professor of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts LUNCH WITH A BIGOT Amitava Kumar, Professor of English, Penn State University, Pennsylvania WHOSE IDENTITY IS IT ANYWAY? Shekhar Deshpande, Associate Professor and Director Communications Program, Arcadia University; Media Editor, ‘Little India Magazine’, Glenside, PA PROFILE OF A DIASPORIC COMMUNITY Sonalde Desai, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Maryland, MD and Rahul Kanakia, student, Stanford University, California ARTS AND THE DIASPORA Vidya Dahejia, holds the Barbara Stoler Miller Chair of Indian Art at Columbia University, New York, and is Director of Columbia’s Southern Asian Institute, NY CONSTRICTING HYBRIDITY Rajika Puri, is an exponent of Bharatnatyam and Odissi; Contributing Editor, ‘NewsIndia Times’, New York THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS Sangeeta Ray, Associate Professor of English, University of Maryland, MD WASHINGTON’S NEW STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP Robert M. Hathaway, Director, South Asia Program, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington DC LIVING THE AMERICAN DREAM Marina Budhos, author, Maplewood, New Jersey LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION Mira Kamdar, Senior Fellow, World Policy Institute at New School University, New York BOOKS Reviewed by Aloka Parasher-Sen, Ratnakar Tripathy and Rajat Khosla COMMENT Received from Susan Visvanathan, JNU, Delhi IN MEMORIAM Komal Kothari BACKPAGE COVER Designed by Akila Seshasayee The problem DESPITE a long history of exchange and migration, it is only recently that Indians abroad have started attracting attention. -

Economic Development Challenges for Immigrant Retail Corridors

EDQXXX10.1177/0891242417730401Economic Development QuarterlyGandhi and Minner 730401research-article2017 Article Economic Development Quarterly 2017, Vol. 31(4) 342 –359 Economic Development Challenges for © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Immigrant Retail Corridors: Observations DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0891242417730401 10.1177/0891242417730401 From Chicago’s Devon Avenue journals.sagepub.com/home/edq Akshali Gandhi1 and Jennifer Minner2 Abstract Immigrant entrepreneurship is important to local and regional economies, cultural identity, placemaking, and tourism. Meanwhile, regional conditions, such as the development of suburban immigrant gateway communities and increases in the cost of business ownership, complicate local economic development efforts in urban ethnic districts. This research is presented as a mixed–methods case study of Devon Avenue in Chicago, IL, home to a significant concentration of South Asian–owned immigrant businesses. Challenges and pressures facing businesses are examined through merchant surveys and interviews. Observations reinforce the notion that cultural competency and strong grassroots leadership is vital for economic development planning so that “capitalizing” on an ethnic heritage does not become a tool for commodification or commercial gentrification. Agencies must also be mindful of the impacts associated with suburbanization of immigrant communities and take a long-term, regional approach to planning in ethnic commercial corridors. Keywords commercial corridors, ethnic corridors, immigrant-owned businesses, commercial gentrification Local governments and tourism agencies seek to enhance socioeconomic conditions, such as the development of new and showcase local neighborhoods and retail corridors for suburban immigrant gateway communities (Singer, economic development purposes (Ashutosh, 2008; Hardwick, & Brettell, 2008) and increases in the cost of busi- Loukaitou-Sideris, 2012). -

Petroleum Industry Oral History Project Transcript

PETROLEUM INDUSTRY ORAL HISTORY PROJECT TRANSCRIPT INTERVIEWEE: A.P. Bowsher INTERVIEWER: Aubrey Kerr DATE: July 26, 1991 Tape 1 Side 1 – 47:00 AK: Okay, sorry for the delay, but I'm Aubrey Kerr and today is Friday July the 26 1991 and I'm in the apartment of A.P. Pat Bowsher, and it's apartment number A4, and the name of the building is Hampton Court, right and I'm very pleased to have the opportunity to first of all get some of your vital statistics, and then to work through your career and I guess to start right off with it Pat, first of all, what does the A stand for? PB: The A is for Allison, A-L-L-I-S-O-N. It's a family name. AK: Right. And you were born in Oyama, British Columbia on October 28th, 1909. AK: Right. At that time was Oyama a fair, larger than it is now or was it, has it shrunk, or, what do you say has happened to it. PB: At that time, it was very small, with less than a dozen families there, folks came there in 1908, bought some land cleared it, and planted orchards. AK: Right. Now where had they come from? PB: My father was from the west of England, near Hunterford-Wilshire. The mother was born in Ireland, Northern Ireland and she and my father met but she took employment with a banker in London. AK: England? PB: England, yeah. AK: Right. So they met in the old country and they were married when they decided to immigrate to Canada. -

The Triple Crown (1867-2020)

The Triple Crown (1867-2020) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2020 Authentic (Sept. 5, 2020) f-Swiss Skydiver (Oct. 3, 2020) Tiz the Law (June 20, 2020) Authentic John Velazquez Robby Albarado Manny Franco Authentic Bob Baffert Kenny McPeek Barclay Tagg Spendthrift Farm, MyRaceHorse Stable, Madaket Stables & Starlight Racing Peter J. Callaghan Sackatoga Stable 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug -

DOWNLOAD Sample Pages

Sample Pages from Created by Teachers for Teachers and Students Thanks for checking us out. Please call us at 800-858-7339 with questions or feedback, or to order this product. You can also order this product online at www.tcmpub.com. For correlations to State Standards, please visit www.tcmpub.com/administrators/correlations 800-858-7339 • www.tcmpub.com Immigration Teacher’s Guide Teacher’s Exploring Primary Sources Immigration Teacher's Guide Table of ContentsTable Introduction Why Are Primary Sources Important? 4 Research on Using Primary Sources 6 Analyzing Primary Sources with Students 11 Components of This Resource 15 How to Use This Resource 18 Standards Correlation 23 Creating Strong Questions 28 Primary Source Card Activities Statue of Liberty 31 Mulberry Street in New York City 35 Immigrants on the SS Amerika 39 Registry Hall in Ellis Island 43 Angel Island 47 Eastern European Immigrant Family 51 Mediterranean Immigrants 55 Mexican Immigration 59 Primary Source Reproduction Activities Emigrants of the Globe 63 Looking Backward 69 Inspection Card 75 Ship’s Manifest 81 Naturalization Paper 87 Chinese Labor Application for Return Certificate 93 Mexican Border Immigration Manifest 99 This Is America 105 Culminating Activities Project-Based Learning Activity 111 Document-Based Questions 114 Making Connections Technology Connections 119 Young-Adult Literature Connections 122 Appendix References Cited 123 Answer Key 124 Digital Resources 128 © | Teacher Created Materials 111318—Exploring Primary Sources: Immigration 3 Why Are Primary -

American Geographical Society

American Geographical Society From Exclusionary Covenant to Ethnic Hyperdiversity in Jackson Heights, Queens Author(s): Ines M. Miyares Source: Geographical Review, Vol. 94, No. 4 (Oct., 2004), pp. 462-483 Published by: American Geographical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30034291 Accessed: 15-06-2015 21:01 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Geographical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Geographical Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 146.96.145.15 on Mon, 15 Jun 2015 21:01:32 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions FROMEXCLUSIONARY COVENANT TO ETHNIC HYPERDIVERSITYIN JACKSONHEIGHTS, QUEENS* INES M. MIYARES ABSTRACT. When EdwardMacDougall of the QueensboroRealty Company originally envi- sioned and developed JacksonHeights in Queens, New Yorkin the earlytwentieth century, he intended it to be an exclusivesuburban community for white, nonimmigrantProtestants within a close commute of Midtown Manhattan.He could not have anticipated the 1929 stock marketcrash, the subsequentreal estate marketcollapse, or the changein immigration policies and patternsafter the 1950s. This case study examineshow housing and public trans- portation infrastructureintended to prevent ethnic diversitylaid the foundation for one of the most diversemiddle-class immigrant neighborhoods in the United States.Keywords: im- migrantneighborhoods, New YorkCity, public transportation,Queens. -

2019 Spring Meet Media Guide

SANTA ANITA PARK 2019 SPRING MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 24-25 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 26-27 Santa Anita on Radio . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 27 Frank Mirahmadi Biography . 5 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 28 Jay Slender Biography . 5 Melair Stakes . 28 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 6 Monrovia Stakes . 29 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 6 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 7 Santa Barbara Stakes . 33-33 Santa Anita Spring 2018 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 7 Santa Margarita Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 8 Santa Maria Stakes . 36-37 Santa Anita Track Records . 9 Senorita Stake . 38-39 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 10 Shoemaker Mile . 40-41 Santa Anita 2018 Spring Meet Standings . 11 Singletary Stakes . 42 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 12 Snow Chief Stakes . 42 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 13 Summertime Oaks . 43-44 2018 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 14 Thor's Echo Stakes . 44 2018 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 14 Tokyo City Cup . 44-45 Stakes Histories . 15 Triple Bend Stakes . 46-47 Affirmed Stakes . 16 Wilshire Stakes . 48 American Stakes . 17-18 Satellite Wagering Directory . 49 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 18-19 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 50-51 Daytona Stakes . 20 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 52 Desert Stormer Stakes . 20 Local Hotels and Restaurants . 53 Dream of Summer Stakes . 20 Racing/Publicity Contacts and Credits . -

Reconnecting with Jackson Heights, New York's Little India

In Focus | RETURN TO ROOTS U.S.A. At Home ABROAD RECONNECTING WITH JACKSON HEIGHTS, NEW YORK’S LITTLE INDIA E R Considered one of the most AMY/INDIAPICTU diverse and multicultural AL I/DINODIA (XXXXXXXXX) R neighbourhoods in New York City, Jackson Heights is so much more than a South D LEVINE/ R O SCOZZA R Asian enclave. IET By Piyali Bhattacharya XXXXXXXXXXXX P RICHA 106 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC TRAVELLER INDIA | JULY 2014 JULY 2014 | NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC TRAVELLER INDIA 107 RETURN TO ROOTS U.S.A. In Focus | hen most Indian-Americans consider a “return to roots”, they usually mean that they’d like to spend some time in India rediscovering their heritage and identity. But when I go back to the place of my origin, I take a journey to the country that lies on the other side of that hyphen. Although I went to school in Westchester County, just north of Manhattan, I decided to study for a year at Delhi University, and after college, moved to the city to work. I married a 1 Delhiite and we became a Global Indian Couple. We’ve made our home in both America and in India, trying to fly back and forth between the two as often as possible. Going back to the country of my birth has always involved a trip to Jackson Heights, one of the dozens of ethnic enclaves around New York City. Like Southall in London, Jackson Heights is lined with nostalgic images of “home”: Bollywood posters and Kishore Kumar songs blaring on a stereo in the distance; whiffs of chicken tikka masala wafting through the air vents of subway stations; and the general sense of a busy marketplace and gossip corner come dusk. -

View Transcript

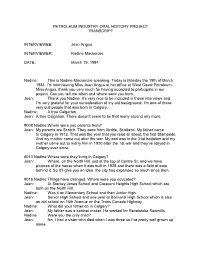

PETROLEUM INDUSTRY ORAL HISTORY PROJECT TRANSCRIPT INTERVIEWEE: Jean Angus INTERVIEWER: Nadine Mackenzie DATE: March 19, 1984 Nadine: This is Nadine Mackenzie speaking. Today is Monday the 19th of March 1984. I’m interviewing Miss Jean Angus at her office at West Coast Petroleum. Miss Angus, thank you very much for having accepted to participate in our project. Can you tell me when and where were you born. Jean: Thank you Nadine. It’s very nice to be included in these interviews and I’m very grateful for your consideration of my old background. I’m one of these very dull people that was born in Calgary. Nadine: A true Calgarian. Jean: A true Calgarian. There doesn’t seem to be that many around any more. #008 Nadine: Where were you parents from? Jean: My parents are Scotch. They were from Airdrie, Scotland. My father came to Calgary in 1912. That was the year that you read all about, the first Stampede. And my mother came out after the war. My dad was in the 31st battalion and my mother came out to marry him in 1920 after the 1st war and they’ve stayed in Calgary ever since. #013 Nadine: Where were they living in Calgary? Jean: Where, on the North Hill, just at the top of Centre St. and we have pictures of the house when it was built in 1925 and there was a field of oats behind it. So it’ll give you an idea, the city has expanded so much since then. #016 Nadine: Things have changed.