LOS DAMA! SYNTHESIS REPORT May 2020 2 INDEX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4Th Issue May 2021 in This Issue 4Th Issue May 2021

#4 4TH ISSUE MAY 2021 IN THIS ISSUE 4TH ISSUE MAY 2021 03 PROGRESS OVER THE PAST 6 MONTHS 04 THE FIRST TWO YEARS OF ACTIVITY 06 THE ITALIAN PILOT OF FASTER PROJECT; MONCALIERI (TURIN) 10 THE FINNISH PILOT OF FASTER PROJECT; KAJAANI (KAINUU) 12 JOINT ACTIVITY WITH OTHER EU H2020 PROJECTS 14 THE FASTER PROJECT PATH TO SUSTAINABILITY PROGRESS OVER THE PAST 6 MONTHS n the last six months a lot of re- demonstrations to be held in the Isults have been achieved and all final months of the project, at the technical tools have been tested in beginning of next year. FASTER has three trial demonstrations (Spain, Italy and Finland). Following these Furthermore, FASTER partners completed the demonstrations, an online debrie- have presented information in 2nd year of its fing meeting was held for each several national and international of the demos with the first re- events with the aim of spreading lifecycle. sponders involved. The purpose news on FASTER and its develop- of these meetings was to collect ments. More info about the events their comments and suggestions are on the FASTER website in the to fine- tune FASTER technolo- Conferences section. gies making them compatible with the existing procedures. Now the technical teams are working to update the tools that will be te- sted in the 2nd and final round of Italian pilot control room in Turin, Piedmont; 27th of January 2021 FASTER NEWSLETTER 3 THE FIRST TWO YEARS OF ACTIVITY FASTER is a 3-year H2020 project that aims to address the challen- ges associated with the protection of First Responders (FRs) in hazar- dous environments, while at the same time enhancing their capabi- lities in terms of situational aware- ness and communication. -

Reply to Editor Thank You Again for Your Interesting Submission "Low Cost, Multiscale and Multi-Sensor Application for Floo

Reply to Editor Thank you again for your interesting submission "Low cost, multiscale and multi-sensor application for flooded areas mapping" as well as for the response to the comments of the referees. The referees agree that the manuscript is of interest for the readers of NHESS and the flood risk community. Combining the reports, it appears to be necessary to provide more details about data and data processing steps as well as quantitative information about the performance and accuracy of classifications. Further, the need was stressed to provide a flow chart of the data sources, processing steps and results. AC: Dear Kai Schröter, We would like to thank you for the reading of the manuscript discussion. Following the suggestion of the referees we provided to improve the manuscript. In particular, we gave more detail about Como-Skymed and MODIS data processing. We also add more quantitative results in the discussion chapter as required by the referees. We also add a flow chart showing the flood mapping strategy used for this work. (Fig. 13). We also improved figure 4 and figure 9 respect to the first submission. In addition, I would like to emphasize that you conduct a thorough English proof-reading and check of correct referencing, e.g. Guy et al. ,2015 is actually Schumann et al., 2015. Please also make sure to correctly and consistently reference online sources. AC: We revised English, using an advanced grammar proofreading software and with a careful re-reading and we corrected the wrong references. Your responses seem to take-up the constructive comments of the referees and will allow to present your approach and results more clear. -

Allegati Relazione

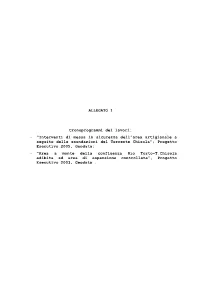

ALLEGATO 1 Cronoprogrammi dei lavori: - “Interventi di messa in sicurezza dell’area artigianale a seguito delle esondazioni del Torrente Chisola”; Progetto Esecutivo 2005, Geodata; - “Area a monte della confluenza Rio Torto-T.Chisola adibita ad area di espansione controllata”, Progetto Esecutivo 2003, Geodata . Opere di sistemazione idrogeologica dell'area a monte della confluenza Rio Torto - Torrente Chisola adibita ad area di espansione controllata gen 04 feb 04 mar 04 apr 04 mag 04 giu 04 lug 04 ago 04 set 04 ott 04 nov 04 dic 04 gen 05 feb 05 m ID Nome attività 29 05 12 19 26 02 09 16 23 01 08 15 22 29 05 12 19 26 03 10 17 24 31 07 14 21 28 05 12 19 26 02 09 16 23 30 06 13 20 27 04 11 18 25 01 08 15 22 29 06 13 20 27 03 10 17 24 31 07 14 21 28 1 Realizzazione interventi di sistemazione idrogeologica 2 Installazione cantieri e piste di servizio 3 Realizzazione argini settori sud e ovest 4 Argini settore nord-ovest 5 Argini settore ovest 6 Argini settore sud-ovest 7 Argine sud 8 Difese spondali Torrente Chisola 9 Difese spondali Rio Torto 10 Realizzazione argini est 11 Deviazioni Rio Torto e Torrente Chisola 12 Realizzazione canalizzazioni provvisorie 13 Deviazioni corsi d'acqua 14 Manufatti, argine sud, completamento argini settore est 15 Avanzamento argine sud 16 Realizzazione manufatti 17 Prima fase 18 Realizzazione parziale manufatti 19 Riprofilatura Rio Torto (tratto a valle manufatto) 20 Seconda fase 21 Completamento manufatti 22 Deviazione Rio Torto e Torrente Chisola in alveo naturale 23 Ripristini canalizzazioni provvisorie -

Presentazione Di Powerpoint

Two case history of EMS data application: earthquake in central italy and flooding in Piedmont region Luca Lanteri*, Rocco Pispico*, R. Cremonini** *Arpa Piemonte, Geological and Natural Risk Dipartiment **Arpa Piemonte, Previsional Department Contact: [email protected] Overview of our organization ARPA - The Regional Agency for the Protection of the Environment of Piedmont is a public authority with independent administrative, technical- juridical status. It operates under the oversight of the Regional Government to ensure compliance with the policy guidelines in the fields of forecasting, preventive actions and preservation of the environment Geological and Natural Risk Department - about 15 technician Previsional Metereological Department - about 35 technician ArpaCopernicusPiemonte EMS Mapping User Workshop 2017 20-21 June 2017, EC Joint Research Centre Ispra (Italy) Overview of our organization Our activities Prediction and prevention of anthropic and natural risks Activities of conformity control on installations Water, soil and air quality monitoring Reports on the environment conditions Weather forecast service In case of heavy rain event, ARPA has 24/7 service to control weather forecast and hydrological status of slopes and rivers In italy Copernicus activation is in charge to National Department of Civil Protection (Autorized user) ArpaCopernicusPiemonte EMS Mapping User Workshop 2017 20-21 June 2017, EC Joint Research Centre Ispra (Italy) Analisys, definition and updating of natural processes framework (landslides, flooding, -

D.T3.1.3. Fua-Level Self- Assessments on Background Conditions Related To

D.T3.1.3. FUA-LEVEL SELF- ASSESSMENTS ON BACKGROUND CONDITIONS RELATED TO CIRCULAR WATER USE Version 1 Turin FUA 02/2020 Sommario A.CLIMATE,ENVIRONMENT AND POPULATION ............................................... 3 A1) POPULATION ........................................................................................ 3 A2) CLIMATE ............................................................................................. 4 A3) SEALING SOIL ...................................................................................... 6 A4) GREEN SPACES IN URBANIZED AREAS ...................................................... 9 B. WATER RESOURCES ............................................................................ 11 B1) ANNUAL PRECIPITATION ...................................................................... 11 B2) RIVER, CHANNELS AND LAKES ............................................................... 13 B3) GROUND WATER .................................................................................. 15 C. INFRASTRUCTURES ............................................................................. 17 C1) WATER DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM - POPULATION WITH ACCESS TO FRESH WATER .................................................................................................... 17 C2) WATER DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM LOSS ..................................................... 18 C3) DUAL WATER DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM ..................................................... 18 C4) FIRST FLUSH RAINWATER COLLECTION ................................................ -

Gazzetta Ufficiale Del Regno D'italia N. 132 Del 5 Giugno 1920

" Supplemento alla Gansetta ufnciale ,, del 5 giugno 1920, n. 182 TOMASO DI SAVOIA DUCA DI GENOVA della città di Carmagnola relativo al tor -ente Melk ita del comune di Moriondo Torinese relativo al torrente Bauna e Luogotenente Generale di Sua Maestit Rio della Scarosa o Valle di Aranzone; VITTOfDO EiiANUELE in del comune di Monaalieri relativo al canale del Mulino del Pa- Scolo della Ficea, rio rio torrente Banne, torrente per ; zia di Dio e per volonta della & zi ne Palera, Sauglio, Chisola, torrente Sanzone; RE D'ITALIA del comune di Cogne o del sig. Darbelley avv. Augudo quale In virtù N dell'autorità a i delegata; rappresentante del coate Wan der Staten e Alfredo Iheys-relauvo Visti gli articoli 2 del decreto Luegotenenziale 20 novembre 1916 al torrento Arpisson, Granson, di Lussert, rio del laghetto coronas, n. 1664, sulle derivazioni di reque pubblicho ed I a 3 del relativo rio dei laghi Cours e Tèie, torrente Pianas Bardonaey, Vale lle, Val- tecai araminist ativo eou decreto regolamento o approvato Luogo- monty e Money di Lanson, Os, Posset e Traso; tenenziale 24 gennaio 1911, n. 85: del comune di Brusson relativo al torrente Evançon, Brossen o Vista l'elenco delle la di acque pubblicha per provincia .Torino, Grand Torrent, rio Fruidiere, toreante Fruidiere o torrente de compliato a cura nel Ministero del lavori pubblesi; Chismen; atti Visti gli dellra istruttoria e perita sotto l'impero deUa legge del comune di Sarre relativo ai torrenti Glustda, Loriettaz, Gre- 10 n. novembre agosto 1884, 2644, e del relativo regolamouto 26 nade e di Clourant; n. -

Informa Autorizzazione Tribunale Di Torino N .2 2008 Di Torino Tribunale Autorizzazione Di Volvera

VOLVERA Informa .2 2008 Autorizzazione Tribunale di Torino n di Torino Tribunale Autorizzazione la città di Volvera. la città Anno 2018 n° 1 - Periodico del 2018 n° 1 - Periodico Anno VOLVERAinforma - 1 Il Gruppo Gabiano Holding nella città di Volvera All’interno della superficie comunale della città di Volvera, trova ospitalità la sede del gruppo Gabiano Holding. Una società del gruppo, costituita nel 1997, è Gabiano Telecomunicazioni che promuove prodotti e servizi nel campo delle telecomunicazioni attraverso una struttura commerciale dedicata esclusivamente alle aziende e alle pubbliche amministrazioni operando in qualità di partner direzionale in esclusiva per British Telecom Global Services (BT Italia e BT Enia). La costante crescita di Gabiano Telecomunicazioni è frutto di importanti investimenti realizzati per garantire la sua presenza su gran parte del territorio nazionale concentrando presso gli uffici di Volvera la più alta percentuale di popolazione aziendale del gruppo. Grazie a questa polarizzazione il gruppo offre al territorio continue opportunità di impiego. Presso la sua sede di Volvera Gabiano ha sviluppato il suo centro di eccellenza per le attività di Customer Care (attività di prevendita, assistenza e supporto clienti), gestione commerciale del parco clienti, Formazione e Sviluppo Risorse Umane. Attraverso la consulenza del gruppo Gabiano, l’Amministrazione Comunale della città di Volvera ha recentemente aderito all’accordo quadro Consip SPC2 specificatamente dedicato alla connettività e alle infrastrutture telefoniche del Comune allineandosi in questo modo alle indicazioni dell’Agenzia per l’Italia digitale. Il processo di trasformazione digitale del Comune è anche reso possibile da questa iniziativa che restituirà a tutti i cittadini benefici nella fruizione dei servizi. -

M Onte Tre D Enti

MONTE TRE DENTI - FREIDOUR P Monte Tre Denti - Freidour ARCO N ATURALE P ROVINCIALE 2 P A R C O N AT U R A L E P ROVINCIALE Monte Tre Denti - Freidour Un parco unito con il suo territorio a soli 30 km da Torino Storiche palestre di roccia Un sottobosco bellissimo sospeso fra collina e montagna Straordinari punti panoramici sulla pianura Una ricca fauna e flora, tipica degli ambienti di media montagna Tutto questo a pochi km da Torino! PARCO NATURALE DI RILIEVO PROVINCIALE DEL MONTE TRE DENTI - FREIDOUR ENTE GESTORE: PROVINCIA DI TORINO SERVIZIO AREE PROTETTE E VIGILANZA VOLONTARIA SEDE: Corso Inghilterra, 7 - 10138 Torino TEL: 011 8616254 ARCO [email protected] P www.provincia.torino.it COMUNE DEL PARCO: CUMIANA SEDE: piazza Martiri III Aprile, 3 10040 Cumiana (TO) TEL: 011 9059001 – 011 9058968 www.comune.cumiana.to.it ECNICA DEL ISTITUZIONE DEL PARCO: T L.R. n. 32 dell’ 8 novembre 2004 s.m.i. ALTITUDINE: da 563 a 1445 m s.l.m. C H E D A SUPERFICIE: 822 ha S (m. 669) (m. 1348) (m. 837) (m. 715) (m. 1280) (m. 1216) (m. 885) Basilica di Superga (m. 1150) Monte San Giorgio Frossasco Cantalupa Faro dellaColle Maddalena Aragno Monte Tre Denti – cappella Monte BrunelloRocca Due Denti Colle Rumiano Pur insistendo esclusivamente sul territorio indicazioni su riportate; del Comune di Cumiana il Parco può essere 2. da Giaveno seguire le indicazioni per la agevolmente raggiunto anche dal versante Colletta di Cumiana e procedere pinerolese (Cantalupa, Frossasco, Roletto, verso La Verna – Bastianoni; ARCOPinerolo, San Pietro Val Lemina). -

Potential and Limitations of Open Satellite Data for Flood Mapping

remote sensing Article Potential and Limitations of Open Satellite Data for Flood Mapping Davide Notti 1 , Daniele Giordan 1,* , Fabiana Caló 2 , Antonio Pepe 2 , Francesco Zucca 3 and Jorge Pedro Galve 4 1 National Research Council of Italy, Research Institute for Geo-Hydrological Protection (CNR-IRPI), Strada delle Cacce 73, 10135 Torino, Italy; [email protected] 2 National Research Council (CNR) of Italy, Institute for the Electromagnetic Sensing of the Environment (IREA), via Diocleziano 328, 80124 Napoli, Italy; [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (A.P.) 3 Department of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Pavia, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] 4 Departamento de Geodinámica, Universidad de Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 31 July 2018; Accepted: 17 October 2018; Published: 23 October 2018 Abstract: Satellite remote sensing is a powerful tool to map flooded areas. In recent years, the availability of free satellite data significantly increased in terms of type and frequency, allowing the production of flood maps at low cost around the world. In this work, we propose a semi-automatic method for flood mapping, based only on free satellite images and open-source software. The proposed methods are suitable to be applied by the community involved in flood hazard management, not necessarily experts in remote sensing processing. As case studies, we selected three flood events that recently occurred in Spain and Italy. Multispectral satellite data acquired by MODIS, Proba-V, Landsat, and Sentinel-2 and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data collected by Sentinel-1 were used to detect flooded areas using different methodologies (e.g., Modified Normalized Difference Water Index, SAR backscattering variation, and supervised classification). -

Type of the Paper (Article

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 31 July 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201807.0624.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1673; doi:10.3390/rs10111673 Article Potentiality and Limitations of Open Satellite Data for Flood Mapping Davide Notti1, Daniele Giordan1, Fabiana Caló2, Antonio Pepe2, Francesco Zucca3, Jorge P. Galve4 1 National Research Council of Italy, Research Institute for Geo-Hydrological Protection (CNR-IRPI), Torino, Italy; [email protected], [email protected] 2 National Research Council (CNR) of Italy—Institute for the Electromagnetic Sensing of the Environment (IREA), via Diocleziano 328, 80124 Napoli, Italy; [email protected], [email protected] 3 Università di Pavia, Italy; [email protected] 4 Departamento de Geodinámica, Universidad de Granada, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Satellite remote sensing is a powerful tool to map flooded areas. In the last years, the availability of free satellite data sensibly increased in terms of type and frequency, allowing producing flood maps at low cost around the World. In this work, we propose a semi-automatic method for flood mapping, based only on free satellite images and open-source software. As case studies, we selected three flood events recently occurred in Spain and Italy. Multispectral satellite data acquired by MODIS, Proba-V, Landsat, Sentinel-2 and SAR data collected by Sentinel-1 were used to detect flooded areas using different methodologies (e.g., MNDWI; SAR backscattering variation; Supervised classification). Then, we improved and manually refined the automatic mapping using free ancillary data like DEM based water depth model and available ground truth data. -

Potential and Limitations of Open Satellite Data for Flood Mapping

remote sensing Article Potential and Limitations of Open Satellite Data for Flood Mapping Davide Notti 1 , Daniele Giordan 1,* , Fabiana Caló 2 , Antonio Pepe 2 , Francesco Zucca 3 and Jorge Pedro Galve 4 1 National Research Council of Italy, Research Institute for Geo-Hydrological Protection (CNR-IRPI), Strada delle Cacce 73, 10135 Torino, Italy; [email protected] 2 National Research Council (CNR) of Italy, Institute for the Electromagnetic Sensing of the Environment (IREA), via Diocleziano 328, 80124 Napoli, Italy; [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (A.P.) 3 Department of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Pavia, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] 4 Departamento de Geodinámica, Universidad de Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 31 July 2018; Accepted: 17 October 2018; Published: 23 October 2018 Abstract: Satellite remote sensing is a powerful tool to map flooded areas. In recent years, the availability of free satellite data significantly increased in terms of type and frequency, allowing the production of flood maps at low cost around the world. In this work, we propose a semi-automatic method for flood mapping, based only on free satellite images and open-source software. The proposed methods are suitable to be applied by the community involved in flood hazard management, not necessarily experts in remote sensing processing. As case studies, we selected three flood events that recently occurred in Spain and Italy. Multispectral satellite data acquired by MODIS, Proba-V, Landsat, and Sentinel-2 and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data collected by Sentinel-1 were used to detect flooded areas using different methodologies (e.g., Modified Normalized Difference Water Index, SAR backscattering variation, and supervised classification). -

Evaluation of Nitrogen Non-Point Sources in Po River Near Turin

American Journal of Environmental Sciences 3 (3): 98-105, 2007 ISSN 1553-345X © 2007 Science Publications Evaluation of Nitrogen Non-Point Sources in Po River Near Turin Giuseppe Genon, Franco Marchese DITAG – Dipartimento del Territorio, dell’Ambiente e delle Geotecnologie Politecnico di Torino – C.so Duca degli Abruzzi 24, 10129 - Torino, Italy Abstract: The non-point hydraulic and nitrogen loads in the stretch of Po river upstream and downstream from the city of Turin have been investigated, on the basis of regular data concerning quality and flow rates in the river in different periods of a reference year. The collected data have been organized in terms of hydraulic and mass balances, taking into account input points, affluents and withdrawals, and the missing terms as concern non-point loads or transfer phenomena with surrounding banks and connected aquifers have been identified.From the nitrogen speciation it was possible to distinguish between different contributions to river load, and to estimate presence of agricultural loads, run-off phenomena from impervious urban areas, aquifer connections. All these information can be useful for a better assessment of the surrounding territory in order to improve river quality for different uses. Keywords: River model, nitrogen balance, non-point sources, sampling, river quality INTRODUCTION been chosen in order to define a mass balance for loads calculation. In order to be able to evaluate the effects of In the treatment plant of the city of Turin (SMAT plant) urban area, in the study large river stretch upstream and the city wastewater (one million inhabitants) and a high downstream from the city has been considered.