Moving the Goalpost: “Come-We-Stay” Practice in Menchum Division (MD), Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

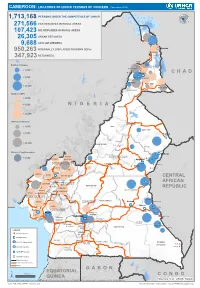

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Blame Attribution in Sexual Victimization ⇑ Carin Perilloux , Joshua D

Personality and Individual Differences 63 (2014) 81–86 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Personality and Individual Differences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/paid Blame attribution in sexual victimization ⇑ Carin Perilloux , Joshua D. Duntley 1, David M. Buss University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, United States article info abstract Article history: The current study explored how victims and third-parties attribute blame and perpetrator motivation for Received 13 October 2013 actual sexual victimization experiences. Although we do not assert that victims are responsible for per- Received in revised form 24 January 2014 petrators’ behavior, we found that some victims do not allocate all blame to their perpetrator. We sought Accepted 25 January 2014 to examine how victims and third-parties allocate blame in instances of actual completed and attempted sexual victimization and how they perceived perpetrator motivations. Victims of completed rape (n = 49) and attempted sexual assault (n = 91), and third-parties who knew a victim of sexual assault (n = 152) Keywords: allocated blame across multiple targets: perpetrator, self/victim, friends, family, and the situation. Partic- Rape ipants also described their perceptions of perpetrator’s motivation for the sexual assault. Victims tended Blame Perpetrator to assign more blame to themselves than third-parties assigned to victims. Furthermore, victims per- Victim ceived perpetrators as being more sexually-motivated than third-parties did, who viewed perpetrators Sexual violence as more power-motivated. Results suggest that perceptions of rape and sexual assault significantly differ between victims and third-party individuals who have never directly experienced such a trauma. Ó 2014 Elsevier Ltd. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

What Bullying Is What Bullying Can Look Like in Elementary School What Bullying Can Look Like in Junior High School

FS-570 BulliesBullies When I was a young boy, What bullying is What bullying the bully called me names, stole my bicycle, forced With all the focus that has surrounded can look like in me off the playground. teenage gangs and gun violence, it may elementary school be easy to forget that the teenage years He made fun of me in are not the only times that children face Being a victim is the most common front of other children, violent behavior. In fact, aggressive in second grade, and the likelihood of forced me to turn over behavior and bullying are even more being bullied decreases each year after my lunch money each day, common in elementary school than in that (see Figure 1). Bullies in elementary threatened to give me junior and senior high! Some studies school are more likely to pick on children a black eye if I told suggest that around 20 percent of all younger than themselves. Bullying is adult authority figures. American children have been the victim often very physical in nature, with open At different times I was of bullying at some point in elementary attacks of aggression being the most subject to a wide range of school, and about the same number common. Boys are more likely to be degradation and abuse – have described themselves as engaging doing the bullying, but girls and boys de-pantsing, spit in my face, in some form of bullying behavior. are equally likely to be victims. forced to eat the playground Bullying can range from teasing, to dirt....To this day, their stealing lunch money, to a group of handprints, like a slap students physically abusing a classmate. -

On Gaslighting: How to Dominate Others 31 Without Their Knowledge Or Consent 3 on Questioning Used As a Covert Method 47 of Interpersonal Control

Gaslighting, the Double Whammy, Interrogation, and Other Methods of Covert Control in Psychotherapy and Analysis Gaslighting, the Double Whammy, Interrogation, and Other Methods of Covert Control in Psychotherapy and Analysis THEO. L. DORPAT, M.D. JASON ARONSON INC. Northvale, New Jersey London This book was set in 11 pt. Berkeley Book by Alpha Graphics of Pittsfield, New Hamp shire, and printed and bound by Book-man of North Bergen, New Jersey. Copyright © 1996 by Jason Aronson Inc. 10 9 8 7 6 54 3 2 1 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No pan of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from Jason Aronson Inc. except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a maga zine, newspaper, or broadcast. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dorpat, Theodore L Gaslighting, the double whammy, interrogation, and other methods of covert control in psychotherapy and analysis I Theo. L Dorpat. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56821-828-1 l. Psychoanalysis-Moral and ethical aspects. 2. Control (Psychology) 3. Psychotherapist and patient-Moral and ethical aspects. 4. Mental suggestion-Moral and ethical aspects. 5. Brainwashing. 6. Manipulative behavior. I. Title. [DNLM: 1. Power (Psychology) 2. Psychotherapy. 3. Psychoanalysis-methods. WM 420 D715i 19961 RCS06.D668 1996 616.89'14-dc20 DNLMIDLC for Library of Congress 96-14098 Manufactured in the United States of America. Jason Aronson Inc. offers books and cas settes. For information and catalog write to Jason Aronson Inc., 230 Livingston Street, Northvale, New Jersey 07647. -

From Migrants to Nationals, from Nationals To

International Journal of Latest Engineering and Management Research (IJLEMR) ISSN: 2455-4847 www.ijlemr.com || Volume 03 - Issue 06 || June 2018 || PP. 10-19 From Nomads to Nationals, From Nationals to Undesirable Elements: The Case of the Mbororo/Fulani in North West Cameroon 1916-2008 A Historical Investigation Jabiru Muhammadou Amadou (Phd) Higher Teacher Training College Department of History The University of Yaounde 1 Abstract: The Fulani (Mbororo) are a minority group perceived as migrants and strangers by local North West groups who consider themselves their hosts and landlords. They are predominantly nomadic people located almost exclusively within the savannah zone of West and Central Africa. Their original homeland is said to be the Senegambia region. From Senegal, the Fulani continued their movement along side their cattle and headed to Northern Nigeria. Uthman Dan Fodio‟s 19th century jihad movement and epidemic outbreaks force them to move from Northern Nigeria to Northern Cameroon. From Northern Cameroon they moved down South and started penetrating the North West Region in the early 20th century. This article critically examines and considers the case of the Fulani in the North West Region of Cameroon and their recent claims to regional citizenship and minority status. The paper begins by presenting the migration, settlement and ultimate acquisition of the status of nationals by the nomadic cattle Fulani in North West Cameroon. It also analysis the difficulties encountered by this nomadic group to fully integrate themselves into the region. In the early 20th century (more precisely 1916) when they arrived the North West Region, they were warmly received by their hosts. -

Transaction-Tax Evasion in the Housing Market José G

Transaction-tax Evasion in the Housing Market José G. Montalvo Amedeo Piolatto Josep Raya This version: January 2020 (March 2019) Barcelona GSE Working Paper Series Working Paper nº 1080 Transaction-tax evasion in the housing market Revised Version January 2020 Jos´eG. Montalvo 1 Amedeo Piolatto2 Josep Raya3 U. Pompeu Fabra-ICREA, Autonomous U. Barcelona, U. Pompeu Fabra, Research Professor BGSE BGSE, IEB, MOVE ESCSE (Tecnocampus) Acknowledgements: We gratefully acknowledges the financial sup- port of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Mont- alvo: ECO2017-82696P, Piolatto: PGC2018-094348; Raya: ECO2016- 78816R), the Government of Catalonia (Montalvo: ICREA-Academia and SGR2017-616; Piolatto: 2017SGR711), the Programa Ram´ony Cajal (Piolatto: RYC-2016-19371), the Severo Ochoa Programme for Centres of Excellence in R&D of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Montalvo and Piolatto: SEV-2015-0563) and the Barcelona GSE. 1Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Ramon Trias Fargas 25-27, 08005 Barcelona. Tel.: +34 935 422 509. E-mail: [email protected] 2[Corresponding Author] Autonomous U. Barcelona (UAB), Bellaterra Campus, 08193, Barcelona. Tel.: Phone: +34 935 868 493 E-mail: [email protected] 3Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Ramon Trias Fargas 25-27, 08005 Barcelona. Tel.: +34 931 696 501. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We model the behaviour of a mortgagor considering to evade the real estate transfer tax. We build an observable measure of over-appraisal that is in- versely related with tax evasion and conclude that the tax authority could focus auditing efforts on low-appraisal transactions. We include `behavi- oural' components (shame and stigma) allowing to introduce buyers' and societal characteristics that explain individual and idiosyncratic variations. -

Recovering from Childhood Abuse

Recovering from Childhood Abuse Sarah Kelly and Jonathan Bird This book is written by survivors for all survivors who experienced any form of abuse or neglect in childhood and for those who provide support. 2014 Copyright © NAPAC 2014 1 Dedication To all the brave survivors and their supporters who have helped us learn what works in recovering from childhood abuse. In memory of those people who could not find the support they needed to survive as adults and tragically took their own lives. All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina People are not disturbed by things, but by the view they take of them. Epictetus, first century AD Thanks to BIG Lottery and all our other generous funders and donors who have made NAPAC’s work and this book possible. Grateful thanks also go to Peter Saunders, Helen Munt, Julie Brock, Kathryn Livingston and Melanie Goodwin of First Person Plural, and Tracey Storey of Irwin Mitchell, who have all contributed to the writing of this book. Proof reading and layout were kindly donated by James Badenoch QC, Ann Watkins and Katie John, and our thanks go to them for their time and efforts. Copyright © NAPAC 2014 2 Contents Page About the authors 4 Foreword – Tim Lambert 5 Introduction 6 Chapter 1: What is abuse? 9 Chapter 2: Maladaptive coping strategies 25 Chapter 3: Mental health 32 Chapter 4: Dissociative spectrum – Katherine and Melanie of FPP 41 Chapter 5: Impacts 49 Chapter 6: Therapy and appropriate coping mechanisms 56 Chapter 7: Transfer of responsibility 67 Chapter 8: How to disclose and how to hear disclosure 80 Chapter 9: The legal process – Tracey Storey, solicitor, Irwin Mitchell 86 Conclusions 96 Bibliography 98 Useful contacts 99 Copyright © NAPAC 2014 3 About the authors Sarah Kelly is a survivor of childhood emotional and sexual abuse. -

N I G E R I a C H a D Central African Republic Congo

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (September 2020) ! PERSONNES RELEVANT DE Maïné-Soroa !Magaria LA COMPETENCE DU HCR (POCs) Geidam 1,951,731 Gashua ! ! CAR REFUGEES ING CurAi MEROON 306,113 ! LOGONE NIG REFUGEES IN CAMEROON ET CHARI !Hadejia 116,409 Jakusko ! U R B A N R E F U G E E S (CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND 27,173 NIGERIAN REFUGEE LIVING IN URBAN AREA ARE INCLUDED) Kousseri N'Djamena !Kano ASYLUM SEEKERS 9,332 Damaturu Maiduguri Potiskum 1,032,942 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSO! NS (IDPs) * RETURNEES * Waza 484,036 Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees MAYO SAVA Mora ! < 10,000 EXTRÊME-NORD Mokolo DIAMARÉ Biu < 50,000 ! Maroua ! Minawao MAYO Bauchi TSANAGA Yagoua ! Gom! be Mubi ! MAYO KANI !Deba MAYO DANAY < 75000 Kaele MAYO LOUTI !Jos Guider Number! of IDPs N I G E R I A Lafia !Ləre ! < 10,000 ! Yola < 50,000 ! BÉNOUÉ C H A D Jalingo > 75000 ! NORD Moundou Number of returnees ! !Lafia Poli Tchollire < 10,000 ! FARO MAYO REY < 50,000 Wukari ! ! Touboro !Makurdi Beke Chantier > 75000 FARO ET DÉO Tingere ! Beka Paoua Number of asylum seekers Ndip VINA < 10,000 Bocaranga ! ! Borgop Djohong Banyo ADAMAOUA Kounde NORD-OUEST Nkambe Ngam MENCHUM DJEREM Meiganga DONGA MANTUNG MAYO BANYO Tibati Gbatoua Wum BOYO MBÉRÉ Alhamdou !Bozoum Fundong Kumbo BUI CENTRAL Mbengwi MEZAM Ndop MOMO AFRICAN NGO Bamenda KETUNJIA OUEST MANYU Foumban REPUBLBICaoro BAMBOUTOS ! LEBIALEM Gado Mbouda NOUN Yoko Mamfe Dschang MIFI Bandjoun MBAM ET KIM LOM ET DJEREM Baham MENOUA KOUNG KHI KOUPÉ Bafang MANENGOUBA Bangangte Bangem HAUT NKAM Calabar NDÉ SUD-OUEST -

Getting Beneath the Surface: Scapegoating and the Systems Approach in a Post-Munro World Introduction the Publication of The

Getting beneath the surface: Scapegoating and the Systems Approach in a post-Munro world Introduction The publication of the Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report (2011) was the culmination of an extensive and expansive consultation process into the current state of child protection practice across the UK. The report focused on the recurrence of serious shortcomings in social work practice and proposed an alternative system-wide shift in perspective to address these entrenched difficulties. Inter-woven throughout the report is concern about the adverse consequences of a pervasive culture of individual blame on professional practice. The report concentrates on the need to address this by reconfiguring the organisational responses to professional errors and shortcomings through the adoption of a ‘systems approach’. Despite the pre-occupation with ‘blame’ within the report there is, surprisingly, at no point an explicit reference to the dynamics and practices of ‘scapegoating’ that are so closely associated with organisational blame cultures. Equally notable is the absence of any recognition of the reasons why the dynamics of individual blame and scapegoating are so difficult to overcome or to ‘resist’. Yet this paper argues that the persistence of scapegoating is a significant impediment to the effective implementation of a systems approach as it risks distorting understanding of what has gone wrong and therefore of how to prevent it in the future. It is hard not to agree wholeheartedly with the good intentions of the developments proposed by Munro, but equally it is imperative that a realistic perspective is retained in relation to the challenges that would be faced in rolling out this new organisational agenda. -

Postfeminist Double Binds

Postfeminist Double Binds: Volume 6 Number 2 How Six Contemporary Films Perpetuate the September 2009 Myth of the Incomplete Woman Samantha Senda-Cook University of Utah Sweet Home Alabama, The Wedding Planner, How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, Down With Love, Never Been Kissed, and Miss Congeniality appear to promote feminist ideals. They feature smart, successful women who are determined to excel at their careers. However, each face a truly difficult decision—the career or the man? In a modern twist on two classic double binds, these six films contrive situations that place the potential male lover in direct opposition to career advancement. In some cases, the women keep their jobs, but in all they prioritize love, specifically “true love.” Additionally, the films each emphasize some transformation that the main character must undergo before she can ultimately succeed personally and professionally. While three films require the woman to relax—not worry so much about her career—the other three depict an ugly-duckling tale. Using Gregory Bateson’s concept of the double bind, Kathleen Hall Jamieson’s articulation of the double binds that women face, and theories of postfeminism, I contend that these films attract a large number of viewers by misusing the tenets of feminism. Furthermore, filmmakers construct arguments subtly and enthymematically. t’s like feminism never even happened, you know? I area in which this happens, I examined six films that assume “Ithink any woman that would do this [enter a beauty women’s ability to gain access to the professional sphere. pageant] is catering to some misogynistic, Neanderthal However, once there, these women must choose between a mentality,” argues the fictitious FBI agent Gracie Hart at successful career and “true love.” I contend that Sweet Home the beginning of Miss Congeniality.1 Ninety minutes later, Alabama, The Wedding Planner, How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, Gracie tearfully accepts the “Miss Congeniality” award Down With Love, Never Been Kissed, and Miss Congeniality in the Miss United States pageant. -

MURPHIE Final Doi UNACCEPTABLE Galleymarch 15

Auditland Andrew Murphie, University of New South Wales Through a silent transformation which … is ... barely possible to analyze, so-called intellectual life is increasingly administered and formatted by the editing and consumption of events … the event goes to market. (François Jullien 2011: 132) Even though this may go against traditional thinking, one could thus speak of an a priori prosthetics. (Bernard Stiegler 2003a) Is this still capitalism? What if it was something worse? (McKenzie Wark 2013) Audit—the ongoing evaluation of performance—began as a fairly narrow range of technical procedures in financial accounting. However, it has now expanded its range to ‘account’ for a wide range of behaviours, thoughts and even feelings, in the workplace and elsewhere. This article first suggests that audit cultures are a response to the ‘abyss of the differential.’ This is the abyss faced when too much generative difference threatens established interests, and thus everything these interests control. Such interests often face a double bind, because they also rely on exploiting generative difference and are thus fully immersed in it. Audit is seen as a useful response to this double bind—to the abyss of the differential. Audit enables both control and ongoing exploitation of the differential. This article secondly aims to summarise some of the recent discussions of audit and then develop aspects of them. Audit technics/cultures use a flexible series of control procedures that differentially declare what is (un)acceptable. They therefore both PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, July 2014. The Unacceptable Special Issue, guest edited by John Scannell.