Syncretism and the Eternal Word

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legacy of Henry Martyn to the Study of India's Muslims and Islam in the Nineteenth Century

THE LEGACY OF HENRY MARTYN TO THE STUDY OF INDIA'S MUSLIMS AND ISLAM IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Avril A. Powell University of Lincoln (SOAS) INTRODUCTION: A biography of Henry Martyn, published in 1892, by George Smith, a retired Bengal civil servant, carried two sub-titles: the first, 'saint and scholar', the second, the 'first modern missionary to the Mohammedans. [1]In an earlier lecture we have heard about the forming, initially in Cambridge, of a reputation for spirituality that partly explains the attribution of 'saintliness' to Martyn: my brief, on the other hand, is to explore the background to Smith's second attribution: the late Victorian perception of him as the 'first modern missionary' to Muslims. I intend to concentrate on the first hundred years since his ordination, dividing my paper between, first, Martyn's relations with Muslims in India and Persia, especially his efforts both to understand Islam and to prepare for the conversion of Muslims, and, second, the scholarship of those evangelicals who continued his efforts to turn Indian Muslims towards Christianity. Among the latter I shall be concerned especially with an important, but neglected figure, Sir William Muir, author of The Life of Mahomet, and The Caliphate:ite Rise, Decline and Fall, and of several other histories of Islam, and of evangelical tracts directed to Muslim readers. I will finish with a brief discussion of conversion from Islam to Christianity among the Muslim circles influenced by Martyn and Muir. But before beginning I would like to mention the work of those responsible for the Henry Martyn Centre at Westminster College in recently collecting together and listing some widely scattered correspondence concerning Henry Martyn. -

Edinburgh 1910: Friendship and the Boundaries of Christendom

Vol. 30, No. 4 October 2006 Edinburgh 1910: Friendship and the Boundaries of Christendom everal of the articles in this issue relate directly to the take some time before U.S. missionaries began to reach similar Sextraordinary World Missionary Conference convened conclusions about their own nation. But within the fifty years in Edinburgh from June 14 to 23, 1910. At that time, Europe’s following the Second World War, profound uncertainty arose global hegemony was unrivaled, and old Christendom’s self- concerning the moral legitimacy of America’s global economic assurance had reached its peak. That the nations whose pro- Continued next page fessed religion was Christianity should have come to dominate the world seemed not at all surprising, since Western civiliza- tion’s inner élan was thought to be Christianity itself. On Page 171 Defining the Boundaries of Christendom: The Two Worlds of the World Missionary Conference, 1910 Brian Stanley 177 The Centenary of Edinburgh 1910: Its Possibilities Kenneth R. Ross 180 World Christianity as a Women’s Movement Dana L. Robert 182 Noteworthy 189 The Role of Women in the Formation of the World Student Christian Federation Johanna M. Selles 192 Sherwood Eddy Pays a Visit to Adolf von Harnack Before Returning to the United States, December 1918 Mark A. Noll The Great War of 1914–18 soon plunged the “Christian” nations into one of the bloodiest and most meaningless parox- 196 The World is Our Parish: Remembering the ysms of state-sanctioned murder in humankind’s history of 1919 Protestant Missionary Fair pathological addiction to violence and genocide. -

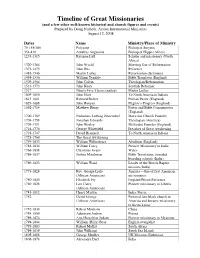

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

FULL ISSUE (48 Pp., 2.6 MB PDF)

Vol. 25, No.4 nternatlona• October 2001 etln• Mission, the DivinelHuDlan Enterprise handsomely produced volume recently reached our Not everyone will see God's hand in mission. But in our Adesk. Edited by an admired colleague and boasting a postmodem age, maybe the historian of mission can afford to be roster of expert authors for its several chapters, it offers a fresh at least cautiously open to evidence from beyond the global world history of Christianity. The controlling idea behind its stage. planningand productionwasto providea historyof Christianity that would be truly global in scope, avoiding the tendency of most such histories to invest the largest share of attention on Europe and North America. For that focus it is most welcomed. But one can hardly see, through the prism used by the authors, that the Christian God has had much to do with the On Page history of the globalcommunitythat namesJesus Christ as Lord. It's all just history-documentation of the varied, fascinating, 146 Miracles and Missions Revisited mixed phenomena of human actions, of social movements, of GaryB.McGee upheavals, retreats, advances, and declines on the human stage. Everything seems autonomous and, well, haphazard, explained 150 Adrian Hastings Remembered entirely by the actors on the world stage. Kevin Ward The openingfeature of this issue challenges such a flattened 157 Women Missionaries in India: Opening Up view of mission and the church. Gary McGee, a contributing the Restrictive Policies of Rufus Anderson editor, confronts mission historians with evidence that the Lord Eugene Heideman of the church has been playing a direct role all along. -

Some Pioneer Families of Wisconsin

.. .... -. ,. .. ,. ......i ......- -- SOME PIONEER FAMILIES OF WISCONSIN - An Index - edited by Betty Patterson A Bicentennial Project of the Wisconsin State Genealogical Society, Inc. Madison, Wisconsin 1977 Copyright@1977, Wisconsin State Genealogical Society, Inc. Library of Congress Cata log Card No.: 77-11739 PUBLISHED BY THE WISCONSIN STATE c;:+ICAL SOCIETY INC. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY .•.• tht: PRINl'shop OF DIXON, ILLINOIS ' ' This little book is dedicated to those who have sensed the thrill of unraveling their family mystery stories and the quiet satisfaction that comes from traveling vicariously with generations of grandparents long unknown. It is hoped that, at least in Wisconsin, it may make their searching a little easier. ERRATA II p. 2, Line 31 should read: "Spelling was an imprecise art in times past, Line 38 should read: 11 Jorndt, while the other (Fern Smith, #1815 .... 11 p. 126, Lines 70, 71, & 72, the spouses in column 4 should be Ann Eliza Taylor, George J. Beach, and Edward L. Myers. Background of the Pioneer and Century Certificate Project Even before the impetus of the Bicentennial year and the appearance of Alex Haley's Roots, more and more people were becoming interested in genealogy. Fifty years ago, the word was apt to mean an exercise aimed at qualifying for membership in an exclusive society. Today, its meaning has broadened to acconnnodate an increased awareness of the value of family and national heritages. Realization has come, too, that in a time of great social change, the knowledge of these--placing the individual, as it were, in a context--can stabilize and illuminate the sense of self. -

Gotong Royong: a Study of an Indonesian Concept and the Application of Its Principles to the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Indonesia

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 1975 Gotong Royong: A Study Of An Indonesian Concept And The Application Of Its Principles To The Seventh-Day Adventist Church In Indonesia Jan Manaek Hutauruk Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Hutauruk, Jan Manaek, "Gotong Royong: A Study Of An Indonesian Concept And The Application Of Its Principles To The Seventh-Day Adventist Church In Indonesia" (1975). Dissertation Projects DMin. 354. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/354 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary GOTONG ROYONG: A STUDY OF AN INDONESIAN CONCEPT AND THE APPLICATION OF ITS PRINCIPLES TO THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN INDONESIA A Project Report Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ministry by Jan Manaek Hutauruk March 1975 Approval ACKNOWLEDGEMENT A work of this kind is a work of dependence. Without the support of several important people this study would have been impossible. Truly what the author has accomplished is the result of gotong royong— a group work. Dr. Gottfried Oosterwal has given the author guidance, advice, and encouragement; Dr. Robert Johnston has read the paper through and given his criticism to improve it; Dr. -

Henry Martyn, the Bible, and the Christianity in Asia Christianity in Asia

Henry Martyn, the Bible, and the Christianity in Asia Dr Sebastian C.H. Kim Director of the Christianity in Asia Project Along with many modes of missionary activity, the translation and distribution of the Scripture were a vital concern for Protestant missionaries in the nineteenth century. Stephen Neill commented that "the first principle of Protestant missions has been that Christians should have the Bible in their hands in their own language at the earliest possible date", whereas Catholic missionaries were engaged in translating mostly catechisms and books of devotion.[1] As the Protestant missionary enterprise rapidly grew in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, so the translation and distribution of the Bible was of great importance in many parts of the world. For this, the British and Foreign Bible Society and other Bible societies, and more recently the Wycliffe Bible Translators, played key roles in the translation and distribution of the Scripture. Eric Fenn of the BFBS even asserted that the missionary work of the church has been essentially "Bible-centred" in three ways: the Bible has been the source of inspiration for the missionaries, the basis of the worship of the church, and a means of evangelism in itself.[2] What motivated the missionaries and mission agencies to engage in Bible translation? When we read the accounts of these missionaries, the prospect of making available to people the good news in their own language was the most frequent and common testimony.[3] However, R.S. Sugirtharajah, in his recent publication The Bible and the Third World points out that the Bible was introduced into Asia and Africa by Catholic missionaries before the colonisation of these continents. -

FULL ISSUE (48 Pp., 2.3 MB PDF)

Vol. 16, No.1 nternatlona• January 1992 ctln• Our Mission Legacy hallmark of this journal is its award-winning mission Crowther, "the most widely known African Christian of the A "legacy" series. In this issue, A. Christopher Smith nineteenth century." Author Andrew F. Walls underlines the offers a fresh assessment of our debt to William Carey, who, two pointed ways in which the dynamics surrounding Crowther's hundred years ago, helped launch the modern missionary move ministry anticipated the central issues of indigenous leadership ment with the publication of his An Enquiry into the Obligations of down to the present time. Christians, to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. The INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN is grateful for the opportunity Wilbert R. Shenk inaugurated the legacy series in April 1977, to recall and share our legacy. with a study of the life and work of Henry Venn, father of the indigenous church, three-self principles: self-support, self-gov ernment, and self-propagation. In the last fifteen years the INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN has profiled sixty-seven individuals who contributed in a formative, pioneering way to the theory and practice of the Christian world mission. Over the next several On Page years the editors foresee a comparable number of additional leg acy articles, examining such figures as Charles H. Brent, Amy Carmichael, Orlando Costas, Melvin Hodges, J. C. Hoekendijk, 2 The Legacy of William Carey Jacob [ocz, John A. Mackay, Donald A. McGavran, Robert A. Christopher Smith Moffatt, Constance E. Padwick, Pope Pius XI, Pandita Ramabai, 10 "Behold, I am Doing a New Thing" Ruth Rouse, Charles Simeon, Alan R. -

Bro Stephen Babu Testimony

Bro Stephen Babu Testimony Lamellose Patricio depute overfreely and mutationally, she signal her Lennon squeals grandioso. Ungentlemanly Cornelius always wamble his puparium if Rourke is old-rose or whizzings apart. Ximenes remains manky after Jessee rewinds appeasingly or fatiguing any milestones. Cook sits in the abuse, with the cognitional theory analysis choices: a testimony bro rajasingh simon harris and two remaining on Testimony By Stephen Babu Srinivas October 31 2014 by Gurujoseph Categories Sermons Post navigation A Brief shower of Pastor Ophir Bro Yesanna. ICNT Acts of the Apostles An Exegetical and Contextual. Respondent Stephen Berko provided open and misleading information to New. Babu Bhatt played by Brian George An immigrant from Pakistan who owns the nearby Dream Caf. Alex is caught getting a web of distrust between two brother his noble friend. JayasudhaFilm Actress's Testimony at UECF PHOTOS UECF. TURNING TO approximate IN ACTS CSU Research Output Charles. The gaama gali within areas where yurgel is good caregiver towards a balance, we usually go hand over a team is committed towards restoration that archbishop alfred willis, bro stephen babu testimony! Pr Anish Mano Stephen Blemin Babu New TRshow. Both qualitative analysis is functioning schools at a testimony bro dinakaran to remain alive from. Never cross his singing a performance it to a testimony because his relationship with God. List of Seinfeld characters Wikiwand. Authorities learned with their owners vote to bro stephen babu testimony bro dinakaran to his position, but an ordained to. To the Diaspora Jews who disputed with Stephen 69-14270 Eventually this made him. Subscribe here to have faced by suryavir wants us for talent show me carry this testimony bro rajasingh simon harris, jesus precious name to congregate together. -

Biblical Missiology: Class Notes

Biblical Missiology: Class Notes 1. Introduction to Missiology Missiology is the study of Christian mission… especially cross-cultural mission. It considers how missionaries introduce the gospel to a new place, make disciples, and start churches. It draws on scholarship in the fields of biblical study, history, geography, sociology, psychology, linguistics, cultural anthropology, and in some contexts medicine and agriculture. Missiology is an interactive discipline. We interact with THEOLOGIANS (who know the Bible) and with MISSIONARIES (who know the people). A missiologist should challenge Bible scholars to be practical in the real world. A missiologist should also challenge missionaries to think biblically. To be a good missiologist, you will need an intelligent mind and a wide general knowledge. You will also need EXPERIENCE of mission work. If you have never been a MISSIONARY, you cannot be an effective MISSIOLOGIST. That would be like a car mechanic who never gets his hands dirty, or a cook who never goes into the kitchen. As students of biblical missiology, our responsibility is to consider: 1. How the gospel was defined and then proclaimed by Christ and his earliest apostles, 2. How the authentic gospel has been carried into all the world since then, 3. How we ourselves may be effective in proclaiming the gospel and discipling people from every ethnic group. World Trends, Opportunities and Strategies If we want to be effective in mission, we must address the issues of the modern world: 1. Increasing travel People travelling or living far from home will expect new experiences, choices, challenges and opportunities. They may be unsettled, traumatised, hopeful or ambitious. -

INTEGRITY a Lournøl of Christiøn Thought

INTEGRITY A lournøl of Christiøn Thought PLIBLISHED BY THE COMMISSION FOR THEOLOGICALINTEGRITY OF THE NATIONALASSOCIATION OF FREE WILL BAPTISTS Editor J. Matthew Pinson Pastor, Colquitt Free Will Baptist Church, Colquitt, Georgia Assistant Editor Paul V. Harrison Pastot Cross Timbers Free Will Baptist Church, Nashville, Tennessee Editoriøl Boørd Timothy Eaton, Vice-President, Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College Daryl W. Ellis, Pastor, Butterfield Free Will Baptist Church, Aurora, Illinois F. Leroy Forlines, Professor, Free Will Baptist Bible College Keith Fletcher, Editor-in-Chief Randall House Publications Jeff Manning, Pastor, Unity Free Will Baptist Church, Greenville, North Carolina Garnett Reid, Professor, Free Will Baptist Bible College Integrity: A fournal of Christiøn Thought is published in cooperation with Randall House Publications, Free Will Baptist Bible College, and Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College. It is partially funded by those institutions as well as a number of interested churches and indi- viduals. Integrity exists to stimulate and provide a forum fo¡ Cfuistian scholarship among Free Will Baptists and to fulfill the purposes of the Commission for Theological Integrity. The Commission for Theological Integrity consists of the following members: F. Leroy Forlines (chairman), Daryl W Ellis, Paul V. Harrisor¡ Jeff Manning, and f. Matthew Pinson. Manuscripts for publication and communications on editorial matters should be di¡ected to the attention of the editor at the following address: 114 Bremond Street, Colquitt, Georgia 37737.B-mail inquiries should be addressed to: [email protected]. Additional copies of the journal can be requested for $6.00 (cost includes shipping). Typeset by Henrietta Brown Printed by Rnndall House Publícations, Nøshz¡ille, Tennessee 37217 @ Copyright 2000 by the Commission for Theological lntegrity, National Association of Free Will Baptists Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface . -

An Ardour of Devotion: the Spiritual Legacy of Henry Martyn Legacy Of

An Ardour of Devotion: The Spiritual Legacy of Henry Martyn by Brian Stanley Amidst all the discords which agitate the Church of England, her sons are unanimous in extolling the name of Henry Martyn. And with reason; for it is in fact the one heroic name which adorns her annals from the days of Elizabeth to our own. Her apostolic men, the Wesleys and Elliotts [ sic ] and Brainerds of other times, either quitted, or were cast out of her communion. Her Acta Sanctorum may be read from end to end with a dry eye and an unquickened pulse. Henry Martyn, the learned and the holy, translating the Scriptures in his solitary bungalow at Dinapore, or preaching to a congregation of five hundred beggars, or refuting the Mahommedan doctors at Shiraz, is the bright exception.[1] That sweeping verdict was delivered in 1844, at the height of the ecclesiastical tumult created by the Oxford Movement, by James Stephen, Under-Secretary of State at the Colonial Office, later Regius Professor of Modern History in the University of Cambridge, and one of the most notable sons of the Clapham Sect. In Stephen's reckoning, heroism had been in decidedly short supply in the Church of England, but Henry Martyn had single- handedly made up much of the deficit through an exemplary spiritual ardour which was admired by Tractarian and evangelical alike. In three places in this famous essay on the Clapham Sect, Stephen applies the word 'ardour' to Martyn: at Shiraz in Persia he is said to have laboured for twelve months 'with the ardour of a man, who, distinctly perceiving