The Cliffordian Virtue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Sally Shuttleworth and Geoffrey Cantor

1 Introduction Sally Shuttleworth and Geoffrey Cantor “Reviews are a substitute for all other kinds of reading—a new and royal road to knowledge,” trumpeted Josiah Conder in 1811.1 Conder, who sub- sequently became proprietor and editor of the Eclectic Review, recognized that periodicals were proliferating, rapidly increasing in popularity, and becoming a major sector in the market for print. Although this process had barely begun at the time Conder was writing, the number of peri- odical publications accelerated considerably over the ensuing decades. According to John North, who is currently cataloguing the wonderfully rich variety of British newspapers and periodicals, some 125,000 titles were published in the nineteenth century.2 Many were short-lived, but others, including the Edinburgh Review (1802–1929) and Punch (1841 on), possess long and honorable histories. Not only did titles proliferate, but, as publishers, editors, and proprietors realized, the often-buoyant market for periodicals could be highly profitable and open to entrepreneurial exploitation. A new title might tap—or create—a previously unexploited niche in the market. Although the expensive quarterly reviews, such as the Edinburgh Review and the Quarterly, have attracted much scholarly attention, their circulation figures were small (they generally sold only a few thousand copies), and their readership was predominantly upper middle class. By contrast, the tupenny weekly Mirror of Literature is claimed to have achieved an unprecedented circulation of 150,000 when it was launched in 1822. A few later titles that were likewise cheap and aimed at a mass readership also achieved circulation figures of this magnitude. -

James, William, the Will to Believe

James, William. The Will To Believe. London: Adamant Media Corporation, 2005. William James (1842-1910), brother of novelist Henry James, taught physiology, psychology, and philosophy at Harvard University. His philosophical pragmatism and thoroughgoing empiricism deeply influenced subsequent American philosophy. Section I. James constructs a defense of the right to believe religious concepts, though those concepts may not be susceptible of rational proof. Belief is an hypothesis. An hypothesis is alive for the individual if one is willing to act irrevocably upon the hypothesis. Decision between hypotheses is an option. Live options appeal (however marginally) to the individual. Forced options leave no alternatives. Momentous options require staking one’s life on the choice. Genuine options are live, forced, momentous options. Section II. One cannot make facts true simply by believing them. Pascal’s wager (belief promises eternal reward; unbelief eternal damnation. No rational gambler would choose to roll the dice where he might win perdition; that gambler would believe, because, if wrong, he loses nothing) leads to empty belief. Scientists overstate when they urge that no belief should be adopted but on adequate evidence. Section III. Our passions affect our beliefs. Where exists a predisposition to a belief, we require precious few reasons to believe. Our faiths are inherited from those who have gone before us. The more doubtful the faith, the more we rely. We disbelieve hypotheses that seem to us useless. So, faith and empirical evidence intertwine in a way difficult to tease out. Section IV. One must choose by emotion where genuine options occur, but intellectual considerations prove inconclusive. -

Following the Argument Where It Leads

Following The Argument Where It Leads Thomas Kelly Princeton University [email protected] Abstract: Throughout the history of western philosophy, the Socratic injunction to ‘follow the argument where it leads’ has exerted a powerful attraction. But what is it, exactly, to follow the argument where it leads? I explore this intellectual ideal and offer a modest proposal as to how we should understand it. On my proposal, following the argument where it leaves involves a kind of modalized reasonableness. I then consider the relationship between the ideal and common sense or 'Moorean' responses to revisionary philosophical theorizing. 1. Introduction Bertrand Russell devoted the thirteenth chapter of his History of Western Philosophy to the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas. He concluded his discussion with a rather unflattering assessment: There is little of the true philosophic spirit in Aquinas. He does not, like the Platonic Socrates, set out to follow wherever the argument may lead. He is not engaged in an inquiry, the result of which it is impossible to know in advance. Before he begins to philosophize, he already knows the truth; it is declared in the Catholic faith. If he can find apparently rational arguments for some parts of the faith, so much the better: If he cannot, he need only fall back on revelation. The finding of arguments for a conclusion given in advance is not philosophy, but special pleading. I cannot, therefore, feel that he deserves to be put on a level with the best philosophers either of Greece or of modern times (1945: 463). The extent to which this is a fair assessment of Aquinas is controversial.1 My purpose in what follows, however, is not to defend Aquinas; nor is it to substantiate the charges that Russell brings against him. -

European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy, V-2 | 2013 from Doubt to Its Social Articulation 2

European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy V-2 | 2013 Pragmatism and the Social Dimension of Doubt From Doubt To Its Social Articulation Pragmatist Insights Mathias Girel Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/536 DOI: 10.4000/ejpap.536 ISSN: 2036-4091 Publisher Associazione Pragma Electronic reference Mathias Girel, « From Doubt To Its Social Articulation », European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy [Online], V-2 | 2013, Online since 24 December 2013, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/536 ; DOI : 10.4000/ejpap.536 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. Author retains copyright and grants the European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. From Doubt To Its Social Articulation 1 From Doubt To Its Social Articulation Pragmatist Insights Mathias Girel 1 Debunking pathological doubts and sundry variants of skepticism certainly has been one of the most prominent features of Pragmatism since its inception in the early 1870s. Peirce’s theory of inquiry and his 1868-69 series, James’s The Will to Believe, and Dewey’s later The Quest for Certainty – to which the last Wittgenstein, as a non-standard pragmatist, might be added – have offered very different strategies to address this question and to counter skeptical doubts. Extant scholarship already provides substantive accounts of this feature of pragmatism,1 and we find in the classical pragmatists several distinct approaches. I will try to show, in this introductory Essay, how and why the social texture of doubt always lurks in the background, and to do so, I will proceed from this classical thesis to the idea that doubt has a genuinely social articulation, which will allow me to exhibit how the following papers all cast light, in different ways, on this very idea. -

“The Will to Believe” by William James

“The Will to Believe” by William James William James, Thoemmes About the author.. William James (1842-1909), both a philosopher and a psychologist, was an early advocate of pragmatism. He thought that a be- lief is true insofar as it “works,” is useful, or satisfies a function. On this theory, truth is thought to be found in experience, not in judgments about the world. James had a most profound “arrest of life”— one quite simi- lar to Tolstoy’s as described in the first section of these readings. While Tolstoy’s solution to his personal crisis was spiritual, James advocated the development of the power of the individual self. In this effort, James ex- erted a greater influence on twentieth century existential European thought than he did on twentieth century American philosophy. About the work. In his Will to Believe and Other Essays,1 James argues that it is not unreasonable to believe hypotheses that cannot be known or established to be true by scientific investigation. When some hypotheses of ultimate concern arise, he argues that our faith can pragmatically shape future outcomes. Much as in Pascal’s Wager, by not choosing, he thinks, we lose possibility for meaningful encounters. 1. William James. The Will to Believe and Other Essays. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1897. 1 “The Will to Believe” by William James From the reading. “He who refuses to embrace a unique opportunity loses the prize as certainly as surely as if he tried and failed.” Ideas of Interest from The Will to Believe 1. Carefully explain James’ genuine option theory. -

The Philosophy of Religion Contents

The Philosophy of Religion Course notes by Richard Baron This document is available at www.rbphilo.com/coursenotes Contents Page Introduction to the philosophy of religion 2 Can we show that God exists? 3 Can we show that God does not exist? 6 If there is a God, why do bad things happen to good people? 8 Should we approach religious claims like other factual claims? 10 Is being religious a matter of believing certain factual claims? 13 Is religion a good basis for ethics? 14 1 Introduction to the philosophy of religion Why study the philosophy of religion? If you are religious: to deepen your understanding of your religion; to help you to apply your religion to real-life problems. Whether or not you are religious: to understand important strands in our cultural history; to understand one of the foundations of modern ethical debate; to see the origins of types of philosophical argument that get used elsewhere. The scope of the subject We shall focus on the philosophy of religions like Christianity, Islam and Judaism. Other religions can be quite different in nature, and can raise different questions. The questions in the contents list indicate the scope of the subject. Reading You do not need to do extra reading, but if you would like to do so, you could try either one of these two books: Brian Davies, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. Oxford University Press, third edition, 2003. Chad Meister, Introducing Philosophy of Religion. Routledge, 2009. 2 Can we show that God exists? What sorts of demonstration are there? Proofs in the strict sense: logical and mathematical proof Demonstrations based on external evidence Demonstrations based on inner experience How strong are these different sorts of demonstration? Which ones could other people reject, and on what grounds? What sort of thing could have its existence shown in each of these ways? What might we want to show? That God exists That it is reasonable to believe that God exists The ontological argument Greek onta, things that exist. -

Introduction Setting the Scene

Introduction Setting the Scene On 7 April, 1875, mathematics students turning up for their morning lecture at University College London were surprised to see a message chalked on the blackboard. It read, ‘I am obliged to be absent on important business which will probably not occur again.’ The Professor of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics, William Kingdon Clifford, was getting married on that day. He had come to London from Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1871 and was twenty-nine years old. He was highly intellectual, tremendously popular, slightly eccentric and such a brilliant lecturer that he had taken the academic world by storm. His bride to be was Sophia Lucy Jane Lane. She was one year younger than William Clifford and had already begun to establish herself as a novelist and journalist. He and Lucy made a most attractive and lively couple and they drew around them a wide circle of friends from all walks of life. In 1874, when their engagement had been announced, William Clifford received this letter: Few things have given us more pleasure than the intimation in your note that you had a fiancée. May she be the central happiness and motive force of your career, and by satisfying the affections, leave your rare intellect free to work out its glorious destiny. For, if you don’t become a glory to your age and time, it will be a sin and a shame. Nature doesn’t often send forth such gifted sons, and when she does, Society usually cripples them. Nothing but marriage – a happy marriage – has seemed to Mrs Lewes and myself wanting to your future.1 The letter was from his close friend, the publisher, writer, and philosopher George Henry Lewes.SAMPLE Mrs Lewes was, of course, George Eliot. -

Reason, Causation and Compatibility with the Phenomena

Reason, causation and compatibility with the phenomena Basil Evangelidis Series in Philosophy Copyright © 2020 Vernon Press, an imprint of Vernon Art and Science Inc, on behalf of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Philosophy Library of Congress Control Number: 2019942259 ISBN: 978-1-62273-755-0 Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image by Garik Barseghyan from Pixabay. Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Table of contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction xi Chapter 1 Causation, determinism and the universe 1 1. Natural principles and the rise of free-will 1 1.1. “The most exact of the sciences” 2 1.2. -

Dewey and Rorty on Kant

WHY NOT ALLIES RATHER THAN ENEMIES? DEWEY AND RORTY ON KANT István Danka E-mail: [email protected] In my paper I shall investigate Rorty's claim how Kant's philosophy is a reductio ad absurdum of the traditional object-subject distinction. I shall argue that most of the common arguments against Rorty's philosophy are based on the same mistake as some of the common arguments against Kant (shared by Dewey and Rorty as well). Though their philosophies differ in several aspects with no doubt, in their anti-skeptical and hence Anti-Cartesian strategy, central to all three of them, they follow the same sort of argumentation. First I shall make some methodological remarks, distinguishing my sort of critique from traditional Anti-Rortyan strategies. Then I shall identify the two main distinctive features between Dewey and Rorty as the latter's return to certain idealist issues. Third, I shall investigate three Kantian topics in pragmatism: the denial of the subject-object dualism, constructivism, and transcendental argumentation. Finally, I shall focus on the question how transcendental idealism could help a Rortyan in order to avoid the same critique as by which Rorty, following Dewey, attacked Kantians. 1. Methodological remarks 1.1. How not to argue against Rorty Richard Rorty is one of the most criticised contemporary philosophers. In order to avoid a misleading reading of my paper, according to which my purpose would be similar to the most common critiques of him, I must say a word or two why my present line of thought is a radically Rortyan one. -

Reconciling Faith and Reason RICHARD RICE/10 the Small

International Journal for Clergy March Reconciling faith and reason RICHARD RICE/10 To ordain or not RUSSELL STAPLES/14 The small church advantage B. RUSSELL HOLT/18 Ministering through the gift of writing ELEANOR P. ANDERSON/21 Alcohol and the pregnant woman ELIZABETH STERNDALE/25 Religio Communism J. R. SPANGLER/4 Letters/2 • Editorials/23 • Health and Religion/25 • Computer Corner/27 • Biblio File/28 • ShopTalk/31 Letters Computers for my education (considerably less than to "Does the Church Need a Loyal I really appreciated the article "Com some of my friends borrowed). This loan Opposition?" (May 1986). I am in a puters: What You Need to Know" is now being paid along with one that my parish that has great potential for growth (November 1986). Include more articles wife had taken out while she was in but also has a very vocal opposition. I of this type, won't you please, for us college. We owe money to some family need to know if they are out to help me or beginners?—Ronald R. Neall, Upatoi, members, we are making payments on a destroy me. Please send me that follow- Georgia. car, we've had major repairs on our other up editorial ("Identifying the Loyal car, and my wife has had some expensive Opposition," July 1986) and include me • Thanks again for the article on com medical tests. on your bimonthly subscription list.— puters.—Ted Struntz, Lincoln, I want to say that we are not Name withheld. Nebraska. compulsive users of the plastic card. Almost a year has gone by and we More prayers haven't used it at all. -

View This Volume's Front and Back Matter

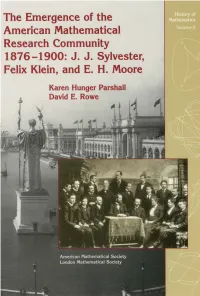

Titles in This Series Volume 8 Kare n Hunger Parshall and David £. Rowe The emergenc e o f th e America n mathematica l researc h community , 1876-1900: J . J. Sylvester, Felix Klein, and E. H. Moore 1994 7 Hen k J. M. Bos Lectures in the history of mathematic s 1993 6 Smilk a Zdravkovska and Peter L. Duren, Editors Golden years of Moscow mathematic s 1993 5 Georg e W. Mackey The scop e an d histor y o f commutativ e an d noncommutativ e harmoni c analysis 1992 4 Charle s W. McArthur Operations analysis in the U.S. Army Eighth Air Force in World War II 1990 3 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part III 1989 2 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part II 1989 1 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part I 1988 This page intentionally left blank https://doi.org/10.1090/hmath/008 History of Mathematics Volume 8 The Emergence o f the American Mathematical Research Community, 1876-1900: J . J. Sylvester, Felix Klein, and E. H. Moor e Karen Hunger Parshall David E. Rowe American Mathematical Societ y London Mathematical Societ y 1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01A55 , 01A72, 01A73; Secondary 01A60 , 01A74, 01A80. Photographs o n th e cove r ar e (clockwis e fro m right ) th e Gottinge n Mathematisch e Ges - selschafft, Feli x Klein, J. J. Sylvester, and E. H. Moore. -

Pragmatism in the Religious Thought of William James

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1960 Pragmatism in the Religious Thought of William James Tomas Francis Ankenbrandt Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Ankenbrandt, Tomas Francis, "Pragmatism in the Religious Thought of William James" (1960). Master's Theses. 1535. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/1535 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1960 Tomas Francis Ankenbrandt PRAG~~TISM IN THE RELIGIOUS THOUGHT or WILLIAM JAMES by Thomas Prancla Ankenbrandt, S. J. A The.i. SUbmitted to the 'aculty of the Graduate School ot Loyola UAly.ra1ty in Partial Fulfillment ot the Requ.irementa for the Degree ot Master or ArtIS January 1960 LIFE Thomas Francis Ankenbrandt, S.J., was born 1n Cleveland, Ohio. January 6, 19)0. He waa graduated fro. St. Ignatius Hlgb Scbool, Cleveland, Oblo. June, 1947, and received tbe degree ot Bachelor ot Arts trom Loyola Univeraity, Chicago, June, 1955. The author entered the Society ot Jesus, August, 1947, and attended cour.e. at the Milford Division of Xavier University, Cinc1nnati, Ohio, Sept_ber. 1947 to June, 19;1. He waa ln India tram 19;1 to 19'3. completing a ,ear of phi1osophioal studies at De Nobl1l Colle,•• POOI'1&, June, 19'3.