Rethinking the Asian Marker Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middle East Oil Pricing Systems in Flux Introduction

May 2021: ISSUE 128 MIDDLE EAST OIL PRICING SYSTEMS IN FLUX INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 THE GULF/ASIA BENCHMARKS: SETTING THE SCENE...................................................................................................... 5 Adi Imsirovic THE SHIFT IN CRUDE AND PRODUCT FLOWS ..................................................................................................................... 8 Reid l'Anson and Kevin Wright THE DUBAI BENCHMARK: EVOLUTION AND RESILIENCE ............................................................................................... 12 Dave Ernsberger MIDDLE EAST AND ASIA OIL PRICING—BENCHMARKS AND TRADING OPPORTUNITIES......................................... 15 Paul Young THE PROSPECTS OF MURBAN AS A BENCHMARK .......................................................................................................... 18 Michael Wittner IFAD: A LURCHING START IN A SANDY ROAD .................................................................................................................. 22 Jorge Montepeque THE SECOND SPLIT: BASRAH MEDIUM AND THE CHALLENGE OF IRAQI CRUDE QUALITY...................................... 29 Ahmed Mehdi CHINA’S SHANGHAI INE CRUDE FUTURES: HAPPY ACCIDENT VERSUS OVERDESIGN ............................................. 33 Tom Reed FUJAIRAH’S RISE TO PROMINENCE .................................................................................................................................. -

Ice Crude Oil

ICE CRUDE OIL Intercontinental Exchange® (ICE®) became a center for global petroleum risk management and trading with its acquisition of the International Petroleum Exchange® (IPE®) in June 2001, which is today known as ICE Futures Europe®. IPE was established in 1980 in response to the immense volatility that resulted from the oil price shocks of the 1970s. As IPE’s short-term physical markets evolved and the need to hedge emerged, the exchange offered its first contract, Gas Oil futures. In June 1988, the exchange successfully launched the Brent Crude futures contract. Today, ICE’s FSA-regulated energy futures exchange conducts nearly half the world’s trade in crude oil futures. Along with the benchmark Brent crude oil, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil and gasoil futures contracts, ICE Futures Europe also offers a full range of futures and options contracts on emissions, U.K. natural gas, U.K power and coal. THE BRENT CRUDE MARKET Brent has served as a leading global benchmark for Atlantic Oseberg-Ekofisk family of North Sea crude oils, each of which Basin crude oils in general, and low-sulfur (“sweet”) crude has a separate delivery point. Many of the crude oils traded oils in particular, since the commercialization of the U.K. and as a basis to Brent actually are traded as a basis to Dated Norwegian sectors of the North Sea in the 1970s. These crude Brent, a cargo loading within the next 10-21 days (23 days on oils include most grades produced from Nigeria and Angola, a Friday). In a circular turn, the active cash swap market for as well as U.S. -

Market Structure, Inventories and Oil Prices: an Empirical Analysis

Market Structure, Inventories and Oil Prices: An Empirical Analysis Jennifer I. Considine and Philipp Galkin and Abdullah Aldayel January 2020 Doi: 10.30573/KS--2020-DP02 Market Structure, Inventories and Oil Prices: An Empirical Analysis 1 About KAPSARC The King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC) is a non-profit global institution dedicated to independent research into energy economics, policy, technology and the environment across all types of energy. KAPSARC’s mandate is to advance the understanding of energy challenges and opportunities facing the world today and tomorrow, through unbiased, independent, and high-caliber research for the benefit of society. KAPSARC is located in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This publication is also available in Arabic. Legal Notice © Copyright 2020 King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (“KAPSARC”). This Document (and any information, data or materials contained therein) (the “Document”) shall not be used without the proper attribution to KAPSARC. The Document shall not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without the written permission of KAPSARC. KAPSARC makes no warranty, representation or undertaking whether expressed or implied, nor does it assume any legal liability, whether direct or indirect, or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information that is contained in the Document. Nothing in the Document constitutes or shall be implied to constitute advice, recommendation or option. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views or position of KAPSARC. Market Structure, Inventories and Oil Prices: An Empirical Analysis 2 Market Structure, Inventories and Oil Prices: An Empirical Analysis Key PointsJennifer I. -

Modified UK National Implementation Measures for Phase III of the EU Emissions Trading System

Modified UK National Implementation Measures for Phase III of the EU Emissions Trading System As submitted to the European Commission in April 2012 following the first stage of their scrutiny process This document has been issued by the Department of Energy and Climate Change, together with the Devolved Administrations for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. April 2012 UK’s National Implementation Measures submission – April 2012 Modified UK National Implementation Measures for Phase III of the EU Emissions Trading System As submitted to the European Commission in April 2012 following the first stage of their scrutiny process On 12 December 2011, the UK submitted to the European Commission the UK’s National Implementation Measures (NIMs), containing the preliminary levels of free allocation of allowances to installations under Phase III of the EU Emissions Trading System (2013-2020), in accordance with Article 11 of the revised ETS Directive (2009/29/EC). In response to queries raised by the European Commission during the first stage of their assessment of the UK’s NIMs, the UK has made a small number of modifications to its NIMs. This includes the introduction of preliminary levels of free allocation for four additional installations and amendments to the preliminary free allocation levels of seven installations that were included in the original NIMs submission. The operators of the installations affected have been informed directly of these changes. The allocations are not final at this stage as the Commission’s NIMs scrutiny process is ongoing. Only when all installation-level allocations for an EU Member State have been approved will that Member State’s NIMs and the preliminary levels of allocation be accepted. -

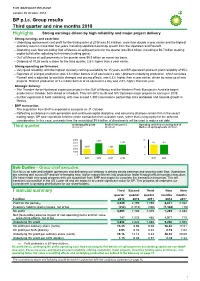

BP P.L.C. Group Results Third Quarter and Nine Months 2018 Highlights Third Quarter Financial Summary

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE London 30 October 2018 BP p.l.c. Group results Third quarter and nine months 2018 Highlights Strong earnings driven by high reliability and major project delivery • Strong earnings and cash flow: – Underlying replacement cost profit for the third quarter of 2018 was $3.8 billion, more than double a year earlier and the highest quarterly result in more than five years, including significant earnings growth from the Upstream and Rosneft. – Operating cash flow excluding Gulf of Mexico oil spill payments for the quarter was $6.6 billion, including a $0.7 billion working capital build (after adjusting for inventory holding gains). – Gulf of Mexico oil spill payments in the quarter were $0.5 billion on a post-tax basis. – Dividend of 10.25 cents a share for the third quarter, 2.5% higher than a year earlier. • Strong operating performance: – Very good reliability, with the highest quarterly refining availability for 15 years and BP-operated Upstream plant reliability of 95%. – Reported oil and gas production was 3.6 million barrels of oil equivalent a day. Upstream underlying production, which excludes Rosneft and is adjusted for portfolio changes and pricing effects, was 6.8% higher than a year earlier, driven by ramp-up of new projects. Rosneft production of 1.2 million barrels of oil equivalent a day was 2.8% higher than last year. • Strategic delivery: – The Thunder Horse Northwest expansion project in the Gulf of Mexico and the Western Flank B project in Australia began production in October, both ahead of schedule. They are BP’s fourth and fifth Upstream major projects to start up in 2018. -

Impact of Low Oil Price on Energy Security Impact of Low Oil Price on Energy Security

APEC Oil and Gas Security Studies Series 10 APEC Oil and Gas Security Studies Impact of Low Oil Price on Energy Security Impact of Low Oil Price on Energy Security Energy Working Group EWG 01 2016S PRODUCED BY: Series Asia Pacific Energy Research Centre (APERC) Institute of Energy Economics, Japan 10 June 2017 Inui Building, Kachidoki 11F, 1-13-1 Kachidoki Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0054 Japan Tel: (813) 5144-8551 Fax: (813) 5144-8555 E-mail: [email protected] (administration) Website: http://aperc.ieej.or.jp/ FOR: Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Secretariat 35 Heng Mui Keng Terrace, Singapore 119616 Tel: (65) 68 919 600 Fax: (65) 68 919 690 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.apec.org © 2017 APEC Secretariat APEC#217-RE-01.7. ISBN 978-981-11-3850-8 2017 Photographs credited by APERC Impact of Low Oil Price on Energy Security APEC Oil and Gas Security Studies Series 10 Energy Working Group June 2017 EWG 01 2016S PRODUCED BY: Dr Ken Koyama, Mr Ichiro Kutani, Mr Takashi Matsumoto, Mr Tadashi Yoshida Asia-Pacific Energy Research Centre (APERC) Institute of Energy Economics, Japan Inui Building, Kachidoki 11F, 1-13-1 Kachidoki Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0054 Japan Tel: (813) 5144-8551 Fax: (813) 5144-8555 E-mail: [email protected] (administration) Website: http://aperc.ieej.or.jp/ PRODUCED FOR: Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Secretariat 35 Heng Mui Keng Terrace, Singapore 119616 Tel: (65) 68 919 600 Fax: (65) 68 919 690 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.apec.org This research document is available at: http://aperc.ieej.or.jp © 2017 APEC Secretariat APEC#217-RE-01.7 ISBN 978-981-11-3850-8 Photographs credited by APERC ii Foreword During the 11th APEC Energy Ministers’ Meeting (EMM11) held in Beijing, China on 2nd September 2014, the Ministers issued instructions to the Energy Working Group (EWG). -

Petroleum Argus Energy, Investment and Politics

Petroleum Argus Energy, investment and politics Volume XLVIII, 4, 26 January 2018 Fractured world EDITORIAL: China and the US’ US president Donald Trump has decided to impose tariffs on imported solar diverging energy pathways make panels, highlighting the divergent energy pathways envisaged by the world’s investment decisions more dif- largest energy users. China plans to become a global leader in renewable energy ficult for oil and gas producers technology at home and abroad, as it reduces its dependence on domestic coal. But the US aims to become a net energy exporter, as it exploits its shale reserves to reinforce its position as the world’s biggest oil and natural gas producer. Investment in renewable energy could soon rival upstream spending on oil and gas. Global clean energy investment — mainly solar and wind power — reached $334bn last year, consultancy Bloomberg New Energy Finance says. This was around three-quarters of the amount spent on upstream oil and gas, after the oil price slump in 2014-16 spurred an unprecedented decline in investment. China’s investment in clean energy is now at parity with US upstream oil and gas spending. China leads the world in clean energy investment, spending $133bn, or 40pc of the global total, in 2017. A surge in solar power investment accounted for two-thirds of the country’s clean energy total last year. US upstream spending tumbled by 40pc to just $81bn in 2015-16, the IEA says. Higher oil prices are spurring a second year of revived US upstream investment, but China’s ambitious spending plans for clean energy are expected to keep pace. -

Methodology and Specifications Guide Crude Oil Latest Update: January 2019

Methodology and specifications guide Crude oil Latest update: January 2019 Introduction 2 Part V: Corrections 12 How this methodology statement is organized 2 Part VI: Requests for clarifications of data and Part I: Input data 2 complaints 12 Reporting data to Platts 3 What to report 3 Part VII: Definitions of the trading locations for which How to report 3 Platts publishes daily indexes or assessments 13 MOC data publishing principles 3 North Sea 16 West Africa 23 Part II: Security and confidentiality 7 Urals and Mediterranean 27 Persian Gulf 35 Part III: Determining assessments 8 Asia Pacific 42 MOC price assessment principles 8 United States 52 Normalization price adjustment techniques 8 Canada 57 Prioritizing data 9 Latin America 59 Assessment Calculations 9 Futures Assessments 62 Part IV: Platts editorial standards 12 Revision History 64 www.spglobal.com/platts Methodology and specifications guide Crude oil: January 2019 INTRODUCTION market acceptance for any proposed introduction or changes to where one or more reporting entities submit market data methodology. For more information on the review and approval that constitute a significant proportion of the total data upon Platts methodologies are designed to produce price procedures, please visit: https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/ which the assessment is based. assessments that are representative of market value, and of the our-methodology/methodology-review-change particular markets to which they relate. Methodology documents ■■ Part IV explains the process for verifying that published prices describe the specifications for various products reflected All Platts methodologies reflect Platts commitment to comply with Platts standards. by Platts assessments, the processes and standards Platts maintaining best practices in price reporting. -

Permit ID Installation ID Operator Name Installation Name 2013 2014

Installation Operator Name Installation Name 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Permit ID ID DTI1015 204463 Premier Oil E&P UK Ltd Voyager Spirit FPSO 72,740 37,302 36,642 35,981 35,321 34,660 33,999 33,339 DTI1016 202656 Ithaca Energy UK Limited Athena 41,458 40,737 40,015 39,294 0000 DTI9910 207103 EnQuest Heather Limited EnQuest Producer 0 0 14,726 79,970 78,502 77,033 75,565 74,097 CNR International (UK) Petrojarl Banff DTI9950 206523 0 26,039 31,970 31,394 30,818 30,241 29,665 29,088 Limited FPSO Nexen Petroleum U.K. DTI9960 206591 Golden Eagle 0 6,010 26,378 27,736 27,227 26,718 26,209 25,699 Limited Anasuria Operating DTI9991 715 Anasuria 43,325 13,457 41,811 22,330 40,264 39,479 38,684 37,887 Company Limited DTI9999 8 Premier Oil E&P UK Ltd Balmoral 34,174 33,580 32,980 32,379 31,760 31,140 30,513 29,884 GB-DTI0200 2 Centrica Storage Ltd Rough 47/3B 66,144 64,995 63,833 62,658 30,736 30,136 29,530 28,921 GB-DTI0300 3 EnQuest Heather Limited Kittiwake Alpha 61,921 60,846 14,940 29,329 57,547 56,425 55,288 54,148 GB-DTI0400 4 Apache North Sea Limited Forties Alpha 69,336 68,131 66,913 65,682 64,437 63,181 61,909 60,632 GB-DTI0600 6 Apache North Sea Limited Forties Charlie 47,229 46,409 45,579 44,740 43,892 43,037 42,170 41,300 GB-DTI0700 7 Apache North Sea Limited Forties Delta 66,347 65,195 64,029 62,851 61,660 60,458 59,240 58,019 ConocoPhillips (UK) GB-DTI1000 10 Britannia 286,653 281,674 276,637 271,547 266,402 261,207 255,947 250,670 Britannia Limited GB-DTI-1001 693 Chrysaor Limited Lomond 65,871 64,727 63,570 62,400 61,218 60,024 58,815 57,603 GB-DTI-1002 696 Chrysaor Limited Everest North 41,385 40,666 39,939 39,204 38,461 37,711 36,952 36,190 GB-DTI1003 686 Britoil Ltd Bruce 142,795 280,628 137,805 270,538 265,413 260,237 254,997 249,739 Spirit Energy North Sea Oil Sevan Marine GB-DTI-1010 1123 127,129 124,921 122,687 120,430 118,148 115,844 113,512 111,171 Limited Hummingbird GB-DTI1011 18 Perenco UK Limited Thames Alpha 23,338 22,933 0 0 0000 Nexen Petroleum U.K. -

United Kingdom Overview

‹ Countries United Kingdom Last Updated: June 3, 2014 (Notes) full report Overview The United Kingdom is the largest producer of oil and the second-largest producer of natural gas in the European Union. Following years of exports of petroleum and natural gas, the UK became a net importer of all fossil fuels for the first time in 2013. The United Kingdom (UK) is the sixth largest economy in the world, as well as the largest producer of oil and the second-largest producer of natural gas in the European Union (EU). Following years of exports of both fuels, the UK became a net importer of natural gas and crude oil in 2004 and 2005, respectively. Production from UK oil and natural gas fields peaked around the late 1990s and has declined steadily over the past several years as the discovery of new reserves and new production has not kept pace with the maturation of existing fields. The UK became a net importer of petroleum products in 2013, making it a net importer of all fossil fuels for the first time. The UK government, aware of the country's increasing reliance on imported fuels, has developed key energy policies to address the domestic production declines. These include: using enhanced recovery from current and maturing oil and gas fields, promoting energy efficiency, decreasing the use of fossil fuels and thus reliance on imports, promoting energy trade cooperation with Norway, and decarbonizing the UK economy by investing heavily in renewable energy. However, for the UK to decarbonize its economy, huge investments in the energy infrastructure are needed. -

Date: 2..4- 2017 Call Option Deed in Respect Of

DATE: 2..4- 2017 CALL OPTION DEED IN RESPECT OF INTERESTS IN THE SULLOM VOE TERMINAL, THE NINIAN PIPELINE SYSTEM, THE NORTHERN LEG GAS PIPELINE, THE MAGNUS FIELD AND THE MAGNUS SOUTH FIELD Between BP EXPLORATION OPERATING COMPANY LIMITED AND ENQUEST NNS LIMITED UK - 212318988.3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Definitions and Interpretation 1 2. Grant of the Call Option 2 3. Period between signing and exercise of call option 3 4. Termination 3 5. Call Option Guarantee 4 6. General 4 Schedule 1 Form of Call Option Notice 13 Schedule 2 Sale and Purchase Terms 14 1. Definitions and Interpretation 15 2. Agreement to Sell the Additional Sale Interests 33 3. Consideration for the Additional Sale Interests 33 4. Conditions and Termination 34 5. Period between the Call Option Notice Date and Completion 37 6. Completion 37 7. Post Completion 38 8. Seller's Warranties 39 9. Limitations on Seller's Liability and Third Party Claims 40 10. Buyer's Warranties 40 11. Decommissioning, Environment and General Indemnities 40 12. Tax 43 Exhibit 1 Additional Sale Interests Documents 44 Exhibit 2 Consideration Adjustments and payment mechanism 45 Exhibit 3 Period between Signing and Completion 65 Exhibit 4 Completion Obligations 68 Exhibit 5 Seller's Warranties 70 Exhibit 6 Limitations on Seller's Liability 76 Exhibit 7 Buyer's Warranties 82 Exhibit 8 Tax 84 Schedule 3 Form of Call Option Guarantee 89 UK - 212318988.3 THIS DEED is made on I January 2017 BETWEEN: (1) BP EXPLORATION OPERATING COMPANY LIMITED, a company incorporated in England & Wales (company number 00305943), having its registered office at Chertsey Road, Sunbury on Thames, Middlesex, TW16 7BP (the "Seller"); arid (2) ENQUEST NNS LIMITED, a company incorporated in England & Wales (company number 10573715 having its registered office at 5th Floor, Cunard House, 15 Regent Street, London, SW1Y 4LR (the "Buyer"). -

OPEC Chief Says Oil Market Responding Well to Record OPEC+

May 21, 2020 OPEC chief says oil market responding well to "Chinese refiners have lost lots of money on refined oil record OPEC+ cut exports as demand in overseas markets was hit badly by the coronavirus," said Ding Xu of China-based Sublime OPEC is encouraged by a rally in oil prices and strong Info, adding that they would rather focus on the home adherence to its latest output cut, its secretary general market. said, although sources say the group has not ruled For the past two months, a complex refinery was losing out further steps to support the market. money producing gasoline as demand crashed following The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting lockdowns to curb the spread of the coronavirus. Countries, Russia and other allies, a group known as China's retail fuel prices are protected by a minimum Brent OPEC+, are cutting supply by a record 9.7 million crude price of $40 a barrel, however, and home demand barrels per day (bpd) from May 1 to offset a slump in has recovered swiftly, denting exports, said Kostantsa prices and demand caused by the coronavirus Rangelova of JBC Energy. outbreak. Expectations of lower Chinese petrol exports and optimism Oil prices have more than doubled since hitting a 21- over global demand recovery flipped Asia's refining margin year low below $16 in April. So far in May, OPEC+ to a small premium of 4 cents to Brent crude on Tuesday has cut oil exports by about 6 million bpd, according for the first time in about two months.