And UPSTREAM COLOR (US 2013) As Post-Secular Sci-Fi Parables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

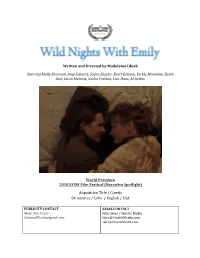

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

Executive Producer)

PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES STEVEN SODERBERGH (Executive Producer) Steven Soderbergh has produced or executive-produced a wide range of projects, most recently Gregory Jacobs' Magic Mike XXL, as well as his own series "The Knick" on Cinemax, and the current Amazon Studios series "Red Oaks." Previously, he produced or executive-produced Jacobs' films Wind Chill and Criminal; Laura Poitras' Citizenfour; Marina Zenovich's Roman Polanski: Odd Man Out, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, and Who Is Bernard Tapie?; Lynne Ramsay's We Need to Talk About Kevin; the HBO documentary His Way, directed by Douglas McGrath; Lodge Kerrigan's Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs) and Keane; Brian Koppelman and David Levien's Solitary Man; Todd Haynes' I'm Not There and Far From Heaven; Tony Gilroy's Michael Clayton; George Clooney's Good Night and Good Luck and Confessions of a Dangerous Mind; Scott Z. Burns' Pu-239; Richard Linklater's A Scanner Darkly; Rob Reiner's Rumor Has It...; Stephen Gaghan'sSyriana; John Maybury's The Jacket; Christopher Nolan's Insomnia; Godfrey Reggio's Naqoyqatsi; Anthony and Joseph Russo's Welcome to Collinwood; Gary Ross' Pleasantville; and Greg Mottola's The Daytrippers. LODGE KERRIGAN (Co-Creator, Executive Producer, Writer, Director) Co-Creators and Executive Producers Lodge Kerrigan and Amy Seimetz wrote and directed all 13 episodes of “The Girlfriend Experience.” Prior to “The Girlfriend Experience,” Kerrigan wrote and directed the features Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs), Keane, Claire Dolan and Clean, Shaven. His directorial credits also include episodes of “The Killing” (AMC / Netflix), “The Americans” (FX), “Bates Motel” (A&E) and “Homeland” (Showtime). -

Film & Event Calendar

1 SAT 17 MON 21 FRI 25 TUE 29 SAT Events & Programs Film & Event Calendar 12:00 Event 4:00 Film 1:30 Film 11:00 Event 10:20 Family Gallery Sessions Tours for Fours: Art-Making Warm Up. MoMA PS1 Sympathy for The Keys of the #ArtSpeaks. Tours for Fours. Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Materials the Devil. T1 Kingdom. T2 Museum galleries Education & 4:00 Film Museum galleries Saturdays & Sundays, Sep 15–30, Research Building See How They Fall. 7:00 Film 7:00 Film 4:30 Film 10:20–11:15 a.m. Join us for conversations and T2 An Evening with Dragonfly Eyes. T2 Dragonfly Eyes. T2 10:20 Family Education & Research Building activities that offer insightful and Yvonne Rainer. T2 A Closer Look for 7:00 Film 7:30 Film 7:00 Film unusual ways to engage with art. Look, listen, and share ideas TUE FRI MON SAT Kids. Education & A Self-Made Hero. 7:00 Film The Wind Will Carry Pig. T2 while you explore art through Research Building Limited to 25 participants T2 4 7 10 15 A Moment of Us. T1 movement, drawing, and more. 7:00 Film 1:30 Film 4:00 Film 10:20 Family Innocence. T1 4:00 Film WED Art Lab: Nature For kids age four and adult companions. SUN Dheepan. T2 Brigham Young. T2 This Can’t Happen Tours for Fours. SAT The Pear Tree. T2 Free tickets are distributed on a 26 Daily. Education & Research first-come, first-served basis at Here/High Tension. -

The 21St Hamptons International Film Festival Announces Southampton

THE 21ST HAMPTONS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES SOUTHAMPTON OPENING, SATURDAY’S CENTERPIECE FILM AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY, SPOTLIGHT AND WORLD CINEMA FILMS INCLUDING LABOR DAY, HER, THE PAST AND MANDELA: LONG WALK TO FREEDOM WILL FORTE TO JOIN BRUCE DERN IN “A CONVERSATION WITH…” MODERATED BY NEW YORK FILM CRITICS CIRCLE CHAIRMAN JOSHUA ROTHKOPF Among those expected to attend the Festival are: Anna Paquin, Bruce Dern, Ralph Fiennes, Renee Zellweger, Dakota Fanning, David Duchovny, Helena Bonham Carter, Edgar Wright, Kevin Connolly, Will Forte, Timothy Hutton, Amy Ryan, Richard Curtis, Adepero Oduye, Brie Larson, Dane DeHaan, David Oyelowo, Jonathan Franzen, Paul Dano, Ralph Macchio, Richard Curtis, Scott Haze, Spike Jonze and Joe Wright. East Hampton, NY (September 24, 2013) -The Hamptons International Film Festival (HIFF) is thrilled to announce that Director Richard Curtis' ABOUT TIME will be the Southampton opener on Friday, October 11th and that Saturday's Centerpiece Film is AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY directed by John Wells. As previously announced, KILL YOUR DARLINGS will open the Festival on October 10th; 12 YEARS A SLAVE will close the Festival; and NEBRASKA is the Sunday Centerpiece. The Spotlight films include: BREATHE IN, FREE RIDE, HER, LABOR DAY, LOUDER THAN WORDS, MANDELA: LONG WALK TO FREEDOM, THE PAST and CAPITAL.This year the festival will pay special tribute to Oscar Award winning director Costa-Gavras before the screening of his latest film CAPITAL. The Festival is proud to have the World Premiere of AMERICAN MASTERS – MARVIN HAMLISCH: WHAT HE DID FOR LOVE as well as the U.S Premiere of Oscar Winner Alex Gibney’s latest doc THE ARMSTRONG LIE about Lance Armstrong. -

Sundance Institute Expands Support to Writers and Creators of Series for TV and Online Platforms

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: March 19, 2014 Casey De La Rosa 310.360.1981 [email protected] Sundance Institute Expands Support to Writers and Creators of Series for TV and Online Platforms First ‘Sundance Institute Episodic Story Lab’ to Be Held in Fall 2014 at the Sundance Resort, with Norman and Lyn Lear as Founding Supporters Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute today announced a significant expansion of its renowned labs for independent artists to include dedicated support for writers and creators of series for television and online platforms. The first Sundance Institute Episodic Story Lab will be held in Fall 2014 at the Sundance Resort in Sundance, Utah. Building on the Institute’s 30-year legacy of developing new work from storytellers with distinctive and risk-taking stories, this new initiative addresses the need for more opportunities for learning and mentorship of singular and diverse voices in scripted TV and online series. In collaboration with accomplished mentors, writers at the six-day, immersive Episodic Story Lab will work on developing stories and characters that play out over multiple episodes and will also have the opportunity to better understand the landscape for production and distribution of serialized stories. Both drama and comedy writing will be supported at the Lab, which has been organized under the leadership of Michelle Satter, Founding Director of the Institute’s Feature Film Program. The Lab is made possible by generous support and guidance from television producer Norman Lear and his wife, Institute Trustee Lyn Lear. The Institute cites the growth of great writing and bold content in recent years as inspiration for the Lab. -

10 Surprising Facts About Oscar Winner Ruth E. Carter and Her Designs

10 Surprising Facts About Oscar Winner Ruth E. Carter and Her Designs hollywoodreporter.com/lists/10-surprising-facts-oscar-winner-ruth-e-carter-her-designs-1191544 The Hollywood Reporter The Academy Award-winning costume designer for 'Black Panther' fashioned a headpiece out of a Pier 1 place mat, trimmed 150 blankets with a men's shaver, misspelled a word on Bill Nunn's famous 'Do the Right Thing' tee, was more convincing than Oprah and originally studied special education. Ruth E. Carter in an Oscars sweatshirt after her first nomination for "Malcolm X' and after her 2019 win for 'Black Panther.' Courtesy of Ruth E. Carter; Dan MacMedan/Getty Images Three-time best costume Oscar nominee Ruth E. Carter (whose career has spanned over 35 years and 40 films) brought in a well-deserved first win at the 91st Academy Awards on Feb. 24 for her Afrofuturistic designs in Ryan Coogler’s blockbuster film Black Panther. 1/10 Carter is the first black woman to win this award and was previously nominated for her work in Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992) and Steven Spielberg’s Amistad (1997). "I have gone through so much to get here!” Carter told The Hollywood Reporter by email. “At times the movie industry can be pretty unkind. But it is about sticking with it, keeping a faith and growing as an artist. This award is for resilience and I have to say that feels wonderful!" To create over 700 costumes for Black Panther, Carter oversaw teams in Atlanta and Los Angeles, as well as shoppers in Africa. -

Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter's Theatre

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2010 Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1645 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 ii © 2010 GRAÇA CORRÊA All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ ______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Daniel Gerould ______________ ______________________________ Date Executive Officer Jean Graham-Jones Supervisory Committee ______________________________ Mary Ann Caws ______________________________ Daniel Gerould ______________________________ Jean Graham-Jones THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa Adviser: Professor Daniel Gerould In the light of recent interdisciplinary critical approaches to landscape and space , and adopting phenomenological methods of sensory analysis, this dissertation explores interconnected or synesthetic sensory “scapes” in contemporary British playwright Harold Pinter’s theatre. By studying its dramatic landscapes and probing into their multi-sensory manifestations in line with Symbolist theory and aesthetics , I argue that Pinter’s theatre articulates an ecocritical stance and a micropolitical critique. -

Fotokem and SPY Combine Talent and Services on Sundance Winner Fruitvale

Media Contacts: ignite strategic communications Chris Purse – [email protected] / 323.806.9696 Lisa Muldowney – [email protected] / 760.212.4130 FotoKem and SPY Combine Talent and Services on Sundance Winner Fruitvale BURBANK and SAN FRANCISCO, January 31, 2013 – FotoKem and SPY (a FotoKem company) combined in-house talent and key post-production services for the Sundance winning film Fruitvale, written and directed by Ryan Coogler with cinematography by Rachel Morrison. The film won the festival’s coveted Grand Jury Prize and Audience Award for a drama, and was acquired by The Weinstein Company soon after its premiere screening. Providing end-to-end services for the Super 16 mm project, FotoKem and SPY worked closely with the filmmakers from start to finish. Fruitvale was processed and transferred at FotoKem in Burbank. The files were delivered to SPY’s headquarters in San Francisco, where colorist Chris Martin color graded the film with Coogler and Morrison. The two facilities are securely connected by a high-speed network offering real-time interface capabilities between the locations to provide the creative community with easy access to the full breadth of post- production services that FotoKem and its companies offer. Fruitvale follows the final day of 22-year old Oscar Grant, who was gunned down by a police officer at the Fruitvale stop of an Oakland transit line. The tragedy was caught on video, and the incident made national headlines. The movie was shot on location in San Francisco. The Super 16 footage was then shipped to Burbank, scanned to HDCAM SR, and conformed at SPY. -

Centrespread Centrespread 15 OCTOBER 23-29, 2016 OCTOBER 23-29, 2016

14 centrespread centrespread 15 OCTOBER 23-29, 2016 OCTOBER 23-29, 2016 As the maximum city’s cinephiles flock to the 18th edition of the Mumbai Film Festival (October 20-27), organised by the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image, ET Magazine looks at some of its most famous counterparts across the world and also in India Other Festivals in IndiaInddia :: G Seetharaman International Film Festivalstival of Kerala Begun in 1996, the festivalstival is believed to be betterter curated than its counterparts in thee Cannes Film Festival (Cannes, France) Venice Film Festival (Italy) country. It is organisedanised by the state governmenternment STARTED IN: 1946 STARTED IN: 1932 TOP AWARD: Palme d’Or (Golden Palm) TOP AWARD: Golden Lion and held annually in Thiruvananthapuram NOTABLE WINNERS OF TOP AWARD: Blow-Up, Taxi Driver, Apocalypse Now, Pulp Fiction, Fahrenheit 9/11 NOTABLE WINNERS OF TOP AWARD: Rashomon, Belle de jour, Au revoir les enfants, Vera Drake, Brokeback Mountain ABOUT: Undoubtedly the most prestigious of all film festivals, Cannes' top awards are second only to the Oscars in their Internationalnal FilmF Festival of India cachet. Filmmakers like Woody Allen, Wes Anderson and Pedro Almodovar have premiered their films at Cannes, which is ABOUT: Given Italy’s great filmmaking tradition — think Vittorio de Sica, as much about the business of films as their aesthetics; the distribution rights for the best of world cinema are acquired by Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni — it is no surprise that the Run jointly by the information and giants like the Weinstein Company and Sony Pictures Classics, giving them a real shot at country hosts one of the finest film festivals in the world. -

PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (Epub)

POST-CINEMA: THEORIZING 21ST-CENTURY FILM, edited by Shane Denson and Julia Leyda, is published online and in e-book formats by REFRAME Books (a REFRAME imprint): http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post- cinema. ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online) ISBN 978-0-9931996-3-9 (PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (ePUB) Copyright chapters © 2016 Individual Authors and/or Original Publishers. Copyright collection © 2016 The Editors. Copyright e-formats, layouts & graphic design © 2016 REFRAME Books. The book is shared under a Creative Commons license: Attribution / Noncommercial / No Derivatives, International 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Suggested citation: Shane Denson & Julia Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). REFRAME Books Credits: Managing Editor, editorial work and online book design/production: Catherine Grant Book cover, book design, website header and publicity banner design: Tanya Kant (based on original artwork by Karin and Shane Denson) CONTACT: [email protected] REFRAME is an open access academic digital platform for the online practice, publication and curation of internationally produced research and scholarship. It is supported by the School of Media, Film and Music, University of Sussex, UK. Table of Contents Acknowledgements.......................................................................................vi Notes On Contributors.................................................................................xi Artwork…....................................................................................................xxii -

Actor Dreyfuss

SATURDAY, AUGUST 23, 2014 Actor Dreyfuss: Politics should be noble calling scar winner Richard tive, among other things, pro- thing, which we do all day Dreyfuss told California vides teachers with videos and long,” the senator from Olawmakers Thursday educational tools. “I want to Escondido said. “We consider that he hopes the public will remind you that it wasn’t that this part of our job, but many, once again view politics as a long ago that there were peo- many, many of our constituents noble calling, and he pledged ple who referred to politicians and many, many young people to do his part through his civics and politics as a noble calling,” surveys show don’t know education initiative. The 66- Dreyfuss told senators at the enough.” year-old actor best known for Capitol. “It hasn’t been lately. Dreyfuss won the Academy “Jaws” and “Close Encounters of And I pledge to get back there Award for best actor in 1977 for the Third Kind” was honored by as soon as possible.” Republican “The Goodbye Girl” and California state lawmakers for Sen Mark Wyland presented received a second nomination his work promoting civics in Dreyfuss with a resolution rec- in 1995 for “Mr. Holland’s public schools. ognizing him for speaking out Opus.” He urged lawmakers to In 2008, he founded The about the deterioration of civics work together for the benefit of Richard Dreyfuss Dreyfuss Initiative, a nonprofit education. future generations. that promotes teaching about Wyland, who has promoted said it’s important to remind tem of government or risk los- “We have a responsibility to American democracy in class- civics education in the San the public about the impor- ing it.