The Green Hand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss

NONPERFORMERS Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss By Barney Hoskyns he history o f American pop music is record of some repute: H e’d cowritten hits with Sam filled with great partnerships. Most Cooke (including the wonderful “Wonderful World”) of them, from Rodgers & Hart to and fellow native Angeleno Lou Adler. But the dark, Jam & Lewis, are songwriting teams handsome trumpeter had little idea of the success in working under pressure to create store once he teamed up with New York—born pro hits for the stars of the day. But motion man Jerry Moss. occasionally fate brings together two highlyThe talented pair’s first label, the short-lived Carnival, was Tmen who create and build a record company with the labnched simply to release two singles they had made same love and dedication that goes into the best songs. independently of each other. “Jerry and I never had A&M Records, the brainchild of Herb Alpert and this master plan o f starting a label,” Alpert has said. “It Jerry Moss, remains one o f the greatest labels launched just happened.” September 1962 saw the release of the in the 1960s, a decade when thousands of independ first A&M single, Alpert’s “The Lonely Bull.” The ents were born in America. Home to an eclectic array mariachi-flavored instrumental struck gold, hitting of outstanding artists from Alpert himself to Janet Number Six by early December of the same year. Jackson, A& M reflected the passion and savvy o f the “For the first couple of years, it was really just two men. -

1970-05-23 Milwaukee Radio and Music Scene Page 30

°c Z MAY 23, 1970 $1.00 aQ v N SEVENTY -SIXTH YEAR 3 76 D Z flirt s, The International Music-Record-Tape Newsweekly COIN MACHINE O r PAGES 43 TO 46 Youth Unrest Cuts SPOTLIGHT ON MCA -Decca in Disk Sales, Dates 2 -Coast Thrust By BOB GLASSENBERG NEW YORK - The MCA - Decca was already well- estab- NEW YORK -Many campus at Pop -I's Record Room. "The Decca Records complex will be lished in Nashville. record stores and campus pro- strike has definitely affected our established as a two -Coast corn- In line with this theory, Kapp moters Records is being moved to the across the country are sales. Most of the students have pany, Mike Maitland, MCA Rec- losing sales and revenue because gone to the demonstrations in West Coast as of May 15. Sev- of student political activity. "The the city and don't have new ords president, said last week. eral employees have been students are concerned with records on their minds at the "There are no home bases any- shifted from Kapp's New York other things at the moment," moment. They are deeply moved more for the progressive record operation into the Decca fold according to the manager of the (Continued on page 40) company." He pointed out that and Decca will continue to be a Harvard Co -op record depart- New York -focused firm. The ment in Cambridge, Mass. The shift of Kapp to Los Angeles is record department does much a "rather modest change," business with students in the FCC Probing New Payola Issues Maitland said, as part of the Boston area. -

ABOUT the RESTORATION This New Digital Restoration Was Undertaken by the Criterion D

“California at that point was PRESENTS everybody’s idea of a new kind of place to find yourself . It wasn’t just the drugs, but the kind of music and the lifestyle that it began to represent.” —D. A. Pennebaker “Monterey was the purest, most beautiful moment of the whole sixties trip . It was a magical, pure moment in time.” —Dennis Hopper “Ralph Gleason and Bill Graham helped bring San Francisco and Los Angeles together. They were the musical ambassadors who really made the festival happen.” —Lou Adler On a beautiful June weekend in 1967, at the beginning of the Summer of Love, the first Monterey International Pop Festival roared forward, capturing a decade’s spirit and ushering in a new era of rock and roll. Monterey featured career-making performances by Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Otis Redding, but they were just a few among a wildly diverse cast that included Simon and Garfunkel, the Mamas and the Papas, the Who, the Byrds, Hugh Masekela, and the extraordinary Ravi Shankar. With his characteristic vérité style, D. A. Pennebaker captured it all, immortalizing moments that have become legend: Pete Townshend destroying his guitar, Jimi Hendrix burning his. ABOUT THE RESTORATION This new digital restoration was undertaken by the Criterion D. A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, and Frazer Pennebaker. Collection with L’Immagine Ritrovata and Metropolis Post. The soundtrack was remastered by Eddie Kramer from the The original 16 mm A/B reversal was scanned in 16-bit 4K original analog 8-track tapes produced by Lou Adler and resolution. The restoration was supervised and approved by John Phillips. -

Delaney & Bonnie Accept No Substitute Mp3, Flac

Delaney & Bonnie Accept No Substitute mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Accept No Substitute Country: US Released: 1969 Style: Southern Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1736 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1492 mb WMA version RAR size: 1735 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 124 Other Formats: WMA XM AU WAV TTA AC3 AU Tracklist 1 Get Oursleves Together 2:33 2 Someday 3:30 3 Ghetto 4:55 4 When The Battle Is Over 3:36 5 Dirty Old Man 2:32 6 Love Me A Little Longer 3:00 7 I Can't Take It Much Longer 3:08 8 Do Right Woman 5:20 9 Soldiers Of The Cross 3:10 10 Gift Of Love 2:55 Credits Arranged By [Strings] – Jimmie Haskell (tracks: A3, B3) Arranged By, Guitar, Piano – Leon Russell Artwork By [Graphics] – Tom Wilkes Backing Vocals – Rita Coolidge Bass Guitar – Carl Radle Drums – Jim Keltner Engineer – John Haeny Guitar – Jerry McGee Lead Vocals, Backing Vocals – Bonnie* Organ, Backing Vocals – Bobby Whitlock Other [Business Management] – Al Leifer, Kaye Wells Other [Councelor] – Owen Sloan Other [Equipment Manager] – Bill Read Other [Management] – Group Three - Alan Pariser Photography – Barry Feinstein Producer, Vocals, Guitar, Arranged By, Backing Vocals – Delaney* Saxophone – Bob Keys* Trumpet, Trombone – Jim Price Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5 099882 315024 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Accept No Substitute (LP, EKS 74039 Delaney & Bonnie Elektra EKS 74039 US 1969 Album) Accept No Substitute (8-Trk, M 84039 Delaney & Bonnie Elektra M 84039 US 1969 Album) Accept No Substitute (LP, EKS -

Het Elpeehoes Ontwerp

Het Elpeehoes ontwerp Abbey Road - The Beatles (1969) Hoesontwerp/ fotografie; Ian MacMillan Een ontspannen Londense zebrapadcompositie met gevoel voor wandelritme. De Beatles dragen effen kleding. De kleuren passen bij de omgeving. John, Ringo, Paul en George lopen langs de Volkswagen Kever (‘Beetle’). Op weg naar en weg van de EMI-studio waar ze hun songs opnemen. Abbey Road wordt de laatste plaat waar ze samen aan werken. Skunk - Doe Maar (1981) Hoesontwerp/ fotografie; Ruud van Wersch Ontwerper Ruud van Wersch (29 jaar) mag geen foto gebruiken voor de hoes van de tweede elpee van Doe Maar. Platenmaatschappij Telstar uit Weert wenst geen herhaling van de ‘schunnigheid’ op het debuutalbum. De hoes moet wel ‘knallen, als een verkeersbord in reggaekleuren’. Ruud gebruikt markeerstiften. Met als resultaat de Skunk postzegel in 2000. 4us - Doe Maar (1983) Hoesontwerp/ fotografie; Hans van Toonen en Hans Wientjes De stijl voor de hoes van de opvolger van Doris Day en andere stukken werd voor de singles van deze lp afkomstig en de eerste Nederlandstalige CD gebruikt. Het ontwerp was van Hans Toonen en Hans Wientjes. Op de voorkant de vier stoere puberale poses van een 25-jarig fotomodel uit Venlo. De Doe Maar kleuren fosforgroen en zuurstokroze domineren ook de binnenhoes, ontworpen door Ansje Thèpass. Dark side of the moon – Pink Floyd (1973) Hoesontwerp/ fotografie; Aubrey Powell en Storm Thorgerson Pink Floyd wil een simpel ontwerp op basis van de lichtshow en de songteksten. Ontwerper Thorgerson kiest voor een prisma. De lichtbundel loopt van de buitenhoes door naar de binnenhoes en vormt zo de hartslag waar het bij deze muziek om draait. -

Beggars Banquet When Is an Album Born?

Beggars Banquet When is an album born? Is it when the first lyrics are written? The first notes played? The first track is laid down? Or is it later, when the accumulated efforts of the artists begin to look like something that needs a name? Or does it take an album cover sleeve? Something from which we remove and return the album, with a strong visual connection? The Stones entered Olympic Studios in London on March 17, 1968 to begin a roughly two-week session during which they would begin recording songs that would appear on Beggars Banquet. The album remained unnamed for 111 days. It would not be released until December 6, 1968 153 days after it was publicly named. Every good Stones fan knows the story of the “graffiti” cover for Beggars Banquet, fewer know that was not the first choice for the album cover. This is the story of how Beggars Banquet came to look like an invitation that was embarrassingly close to the Beatles White Album. The Rolling Stones needed a win, “Cause you see I’m on a losing streak.” Andrew Loog Oldham was gone, Keith who stole Brian’s girl may have had her borrowed by Mick who was filming love scenes with her in Performance as Keith penned Gimme Shelter. The drug busts had slowed but their aftermath churned on, Brian was on his way out and the rock and roll lifestyles went on. After the psychedelic debacle of Their Satanic Majesties Request the new album was a make or break endeavor. Mick had hoped to have the album come out on June 26, his 25th birthday. -

Delaney & Bonnie & Friends on Tour Mp3, Flac

Delaney & Bonnie & Friends On Tour mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Blues / Folk, World, & Country Album: On Tour Country: Australia MP3 version RAR size: 1920 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1580 mb WMA version RAR size: 1278 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 954 Other Formats: ASF APE DTS WMA MP1 MIDI AA Tracklist Hide Credits Things Get Better A1 4:20 Written-By – Floyd*, Cropper*, Wayne* Poor Elijah - Tribute To Johnson (Medley) (5:00) Poor Elijah A2a Written-By – D. Bramlett*, J. Ford* Tribute A2b Written-By – D. Bramlett*, L. Russell* Only You Know And I Know A3 4:10 Written-By – D. Mason* I Don't Want To Discuss It A4 4:55 Written-By – Beatty*, Cooper*, Shelby* That's What My Man Is For B1 4:30 Written-By – Bessie Griffin Where There's A Will, There's A Way B2 4:57 Written-By – B. Whitlock*, B. Bramlett* Coming Home B3 5:30 Written-By – B. Bramlett*, E. Clapton* Little Richard Medley (5:45) Long Tall Sally B4a Written-By – R. Penniman*, R. A. Blackwell* Jenny Jenny B4b Written-By – R. Penniman* The Girl Can't Help It B4c Written-By – R. W. Trout* Tutti-Frutti B4d Written-By – R. Penniman* Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Atlantic Recording Corporation Mastered At – Longwear Plating Mastered At – Atlantic Studios Copyright (c) – Atlantic Recording Corporation Published By – East/Memphis Music Published By – Web IV Music Published By – Metric Music Published By – Irving Music, Inc. Published By – Nelchell Music Published By – Resco Published By – DelBon Music Published By – Cotillion Music Published By – Throat Music Published By – Venice Music Published By – 20th Century Music Credits Arranged By [Horn Arrangements By] – Delaney Bramlett, Jim Price Bass – Carl Radle Congas [Conga], Bongos [Bongo Drums] – Tex Johnson Design, Photography By – Barry Feinstein, Tom Wilkes Design, Photography By [For] – Camouflage Productions Drums – Jim Gordon Engineer [Mix Down Engineer] – Bill Halverson Engineer [Recording Engineers] – Andy Johns, Glyn Johns Guitar – Dave Mason Lead Guitar – Eric Clapton Mastered By – AB* Organ, Vocals – B. -

Beabohema 15

MI BACK PAGES This is the 15th in the series of BeABohema, published biweekly, available for $06. You can also receive BAB by performing one or more of the many other unnatural acts usually reserved for people who don’t wish to palm off half a dollar on a fanzine editor. This is the first page of the newly expanded ”BcB owings”: it’s an ex pansion which goes to encompass the TOC because it’s a bit too much trouble mak ing that one page department a separate entity from the regular editorial when in fact it’s usually a continuation of editorial writing, with perhaps a more strict format. Right. The code on the Tailing label will probably adhere to tradition in that the code letter will mean what you want it to mean. The interpretation had best coincide with what I want it to mean, however. Most people shouldn't have to worry about the code, though. If you’re a writer, I’d like to got some material from you. If you’re an artist, etc. But no one should take this request for ma terial as a demand for anything. Even when I ask for material specifically it’s subject to ray control, so don't get pissed off if I ultimately reject your neat ly written beauties. A number on your label means that issue is the last issue you've paid for. A triple-X means this is your last issue; it means you'd better do something fast. A ? means I’d. -

Jesse 'Ed' Davis Ululu Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jesse 'Ed' Davis Ululu mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Blues Album: Ululu Country: US Released: 1972 Style: Blues Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1706 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1942 mb WMA version RAR size: 1524 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 892 Other Formats: RA ADX AUD RA FLAC VOC AU Tracklist Hide Credits Red Dirt Boogie, Brother A1 3:44 Written-By – Jesse Davis* White Line Fever A2 Backing Vocals – The Charles Chalmers Singers*, Clydie King, Merry Clayton, Vanetta 3:03 Fields*Bass – Arnold RosenthalPiano – Stan Szeleste*Written-By – Merle Haggard Farther On Down The Road (You Will Accompany Me) A3 3:14 Piano – Albhy GalutenWritten-By – Jesse Davis*, Taj Mahal Sue Me, Sue You Blues A4 Backing Vocals – The Charles Chalmers Singers*, Clydie King, Merry Clayton, Vanetta 2:45 Fields*Bass – Billy Rich*Written-By – George Harrison My Captain A5 3:23 Bass – Billy Rich*Organ – Larry KnechtelPiano – Leon RussellWritten-By – Jesse Davis* Ululu B1 3:40 Backing Vocals – Chuck KirkpatrickPiano – Albhy GalutenWritten-By – Jesse Ed Davis Oh! Susannah B2 2:45 Arranged By – Jesse Davis*Written-By [Release Credit] – Trad.* Strawberry Wine B3 2:13 Written-By – Levon Helm, Robbie Robertson Make A Joyful Noise B4 3:51 Written-By – Jesse Davis* Alcatraz B5 3:15 Written-By – Leon Russell Companies, etc. Recorded At – Criteria Recording Studios Recorded At – Record Plant, Los Angeles Recorded At – The Village Recorder Distributed By – Atlantic Recording Corporation Phonographic Copyright (p) – Atlantic Recording Corporation Pressed By – PRC Recording -

Copyrighted Material

c01.qxd 3/29/06 11:47 AM Page 1 1 Expecting to Fly The businessmen crowded around They came to hear the golden sound —Neil Young Impossible Dreamers For decades Los Angeles was synonymous with Hollywood—the silver screen and its attendant deities. L.A. meant palm trees and the Pacific Ocean, despotic directors and casting couches, a factory of illusion. L.A. was “the coast,” cut off by hundreds of miles of desert and mountain ranges. In those years Los Angeles wasn’t acknowl- edged as a musicCOPYRIGHTED town, despite producing MATERIAL some of the best jazz and rhythm and blues of the ’40s and ’50s. In 1960 the music business was still centered in New York, whose denizens regarded L.A. as kooky and provincial at best. Between the years 1960 and 1965 a remarkable shift occurred. The sound and image of Southern California began to take over, replacing Manhattan as the hub of American pop music. Producer Phil Spector took the hit-factory ethos of New York’s Brill Building 1 c01.qxd 3/29/06 11:47 AM Page 2 2 HOTEL CALIFORNIA songwriting stable to L.A. and blew up the teen-pop sound to epic proportions. Entranced by Spector, local suburban misfit Brian Wil- son wrote honeyed hymns to beach and car culture that reinvented the Golden State as a teenage paradise. Other L.A. producers followed suit. In 1965, singles recorded in Los Angeles occupied the No. 1 spot for an impressive twenty weeks, compared to just one for New York. On and around Sunset, west of old Hollywood before one reached the manicured pomp of Beverly Hills, clubs and coffee- houses began to proliferate. -

Rainwater, Lynn 2003 -- 2003 Wise County Messenger

Wise County Messenger Obituaries 2003 Last Names R-Z The following obituaries are in alphabetical order by last name. Rainwater, Lynn 1917-2003 Graveside service for Lynn Rainwater, 87, of Rhome will be at noon on Monday, Sept. 1 at the DFW National Cemetery. The Rev. Gary Sessions will officiate. Visitation will be from 6 to 8 p.m. at Christian-Hawkins Funeral Home in Boyd. Rainwater died on Wednesday, Aug. 27, 2003, in Rhome. Born Feb. 10, 1917 in Vrona, Okla., to Arthur and Rosetta (Howell) Rainwater, he married Johnnie Mozelle on Jan. 6, 1944, in Bridgeport. He served in the U.S. Army and retired as a foreman with the highway department. He was a Baptist and a member of the Masonic Creek Lodge No. 226. He was preceded in death by his wife, parents and three brothers. He is survived by a son, Marshall Travis Rainwater and wife, Ruth; four grandsons, Robert Fowler, Mark Rainwater, Charles Fowler and Keith Rainwater; nine great-grandchildren; seven great-great- grandchildren and Kay Ashley and family, whom he considered family as she helped him with his health needs. Ramsey, Charles M. (Mac) 1920-2003 Family visitation for Charles M. (Mac) Ramsey, 83, of Bridgeport was to be Saturday, Dec. 27, from 3 to 5 p.m. at Hawkins Funeral Home in Bridgeport. A service is not planned. Ramsey died Thursday, Dec. 25, 2003, in Bridgeport. He was born Nov. 20, 1920, in Honey Grove and married Edith Ramsey on June 19, 1946. Ramsey was a U.S. Navy veteran who served in World War II. -

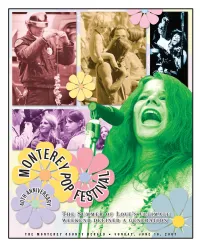

T H E M O N T E R E Y C O U N T Y H E R a L D • S U N D a Y , J U N E

T H E M O N T E R E Y C O U N T Y H E R A L D • S U N D A Y , J U N E 1 0 , 2 0 0 7 MONTEREY INTERNATIONAL POP FESTIVAL ♥ 1967-2007 ♥ THE SUMMER OF LOVE T H E F E S T I V A L “The Pop Festival was an event that altered our world from the inside out. The Monterey International Pop Festival was a seminal event in rock ’n’ roll history — and defined Through our ears, eyes and minds, a new culture redirected the future.” a generation that embraced peace, love and — John Bassett McCleary, author change. The unprecedented bill of musically diverse acts showed rock’s power to change the world. Preceding Woodstock by two years, it was the first major rock festival, the first ever rock charity event and spawned the first ever rock concert movie. For one weekend, June 16-18, 1967, the harsh 40 YEARS AGO realities of the Vietnam War — student unrest, the Cold B y J O H N B A S S E T T M c C L E A R Y War, racism, urban riots, Herald Correspondent poverty and domestic he sun was shining on 30,000 politics — were forgotten music lovers. Even the and even transcended. morning fog sparkled. The artists performed for Harmonica notes flowed Poster by Tom Wilkes free, with all revenue between the oaks and pines. donated to charity through the nonprofit Monterey Festival Foundation. TGuitar riffs tore through leaves.