1 Harriet Sleigh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R.B. Kitaj Papers, 1950-2007 (Bulk 1965-2006)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf0wf No online items Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Processed by Tim Holland, 2006; Norma Williamson, 2011; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj 1741 1 papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Descriptive Summary Title: R.B. Kitaj papers Date (inclusive): 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Collection number: 1741 Creator: Kitaj, R.B. Extent: 160 boxes (80 linear ft.)85 oversized boxes Abstract: R.B. Kitaj was an influential and controversial American artist who lived in London for much of his life. He is the creator of many major works including; The Ohio Gang (1964), The Autumn of Central Paris (after Walter Benjamin) 1972-3; If Not, Not (1975-76) and Cecil Court, London W.C.2. (The Refugees) (1983-4). Throughout his artistic career, Kitaj drew inspiration from history, literature and his personal life. His circle of friends included philosophers, writers, poets, filmmakers, and other artists, many of whom he painted. Kitaj also received a number of honorary doctorates and awards including the Golden Lion for Painting at the XLVI Venice Biennale (1995). He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1982) and the Royal Academy of Arts (1985). -

Chapter One – Introduction

CHAPTER ONE – INTRODUCTION. 1.1 – Time and Colour as Visual Drivers It is generally understood that time and colour constitute an integral part of the great trinity of primary terrestrial and cosmic phenomena i.e., the aggregation of time, light (of which “… colour is a manifestation of a particular wavelengths …” (Collier, 1972: 148)) and space. It is also understood that the perception of one is dependent upon the presence of the other two. The manifestation of time, for instance becomes apparent through the measurement of the distance between objects or points in space. The objects, or points themselves are made visible by the passage of light striking their individual surfaces. How long it takes to get from one object or point to the other provides us with a tangible measure of time. The art historian and sculptor Grahame Collier (1972) reminds us that … space is the arena in which light manifests and this manifestation permits us to discern the layout of objects. Only by perceiving the layout of objects do we become aware of the multidimensional shape of space between them and ultimately the distances involved. Thus we are able to conceive of time… (Collier, 1972: 121). The activities of both the visual artist and architect (whatever their theoretical proclivities may be) are, to one extent or another, concerned with the management and manipulation of space, which of course includes the location of two and three- 1 dimensional forms in space. The artist’s concerns with spatial organization may be engaged at any scale though it is generally, as Collier (1972) remarks, at …a more intimate scale than that of nature; a painting, for example, can become a very personal environment in which even the macro, unarticulated space of sea or sky is transformed into a scale we can apprehend. -

Download PDF Catalogue

AUCTIONEER Nicosia, Cyprus (Head Office) George Kyriacou 14 Evrou Street 2003 Strovolos CATALOGUE SUPERVISION Nicosia, Cyprus Ritsa Kyriacou Phone: +357 22 341122 CATALOGUE-DESIGN-EDITING Phone: +357 97 673876 En Tipis Publications Fax: +357 22 341124 PRINTING Athens, Greece Negresco 42 Lagoumitzi (Flat 5) Neos Kosmos PHOTOGRAPHY Athens, 11745 Christos Andreou Greece Costas Savvides Phone: +30 69944382236 ISBN 978-1-907983-16-0 London, U.K. FRONT COVER 101-103 Heath Street Lot 33 Hampstead Alecos Fassianos London, NW3 6SS United Kingdom BACK COVER Lot 53 Phone: +44 7768365947 Lefteris Economou INFORMATION-BIDS IMPORTANT NOTICE Nicosia The works included in this auction are Ritsa Kyriacou offered in their existing state’’ with Athens the exception of counterfeits for which Michalis Constantinou please see the terms of this auction in the last pages of the catalogue. [email protected] All interested parties are urged www.cypriaauctions.com to examine the works personally before the auction. A detailed report Written bids / Telephone bids for each work can be obtained You can place a written bid or request on request. a telephone bid on the lots you are interested in through our website Artist’s Resale Rights: On lots sold up www.cypriaauctions.com to €50 000 4% will be added to the hammer price, which is the artist’s re- Live online bidding sale right applicable if the artist is alive or has died in the Is available for this auction through last 70 years. www.invaluable.com (For lots sold above €50 000 the Artist’s Resale Right is -

One Day, Something Happens: Paintings of People

One Day, Something Happens: Paintings of People Education information pack Contents Page How to use this pack 2 The Arts Council Collection 2 Introduction to the exhibition 3 Artists and works in the exhibition 5 Glossary of art terms and movements 31 In the gallery – looking at the exhibition 37 Project and activity ideas: 38 Art as storytelling 39 Moments in time – movement and stillness 42 Real people, invented characters 45 A true likeness 48 Expression and abstraction 50 Being human – the inside view 53 Seeing and being seen 55 Art as social documentary 59 Useful websites and further reading 62 Jennifer Higgie – exhibition catalogue essay 63 1 How to use this pack This pack is designed for use by teachers and other educators including gallery education staff. It provides background information about the exhibition and the exhibiting artists, as well as a glossary of key terms and art movements. The pack also contains a selection of project ideas around some key themes. As well as offering inspiration for art, One Day, Something Happens: Paintings of People also links well to literacy, drama, history and geography. The project suggestions are informed by current National Curriculum requirements and Ofsted guidance. They are targeted primarily at Key Stage 2 and 3 pupils, though could also be adapted for older or younger pupils. They may form part of a project before, during, or after a visit to see the exhibition. Information in the pack will also prove useful for pupils undertaking GCSE and ‘A’ level projects. This education information pack is intended as a private resource, to be used for educational purposes only. -

David Hockney

875 N Michigan Ave, Ste 3800 Chicago, IL 60611 +1 312 642 8877 1018 Madison Ave, 2nd Fl New York, NY 10075 +1 212 472 8787 DAVID HOCKNEY Born in Bradford, England, 1937. Currently lives and works in Normandy, France. EDUCATION 1962 Royal College of Art, London, England 1957 Bradford College of Art, Bradford, England SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020, Royal Academy of Arts, London, England Hockney in Normandy, Richard Gray Gallery, New York, New York 2020 David Hockney: Ma Normandie, Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris, France David Hockney: Drawing from Life, The Morgan Library and Museum, New York, New York [cat.] (2021) David Hockney: Video Brings Its Time to You, You Bring Your Time to Paintings and Drawings, Annely Juda Fine Art, London, England David Hockney: Drawing from Life, National Portrait Gallery, London, England David Hockney: Works from the Tate Collection, Bucerius Kunst Forum, Hamburg, Germany 2019 David Hockney's Yosemite, Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona (2020) Alan Davie & David Hockney: Early Works, The Hepworth Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England (2020) David Hockney: La Grande Cour Normandy, Pace Gallery, New York, New York [cat.] Hockney and Hollywood, The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, England David Hockney's Yosemite, Monterey Museum of Art, Monterey, California David Hockney, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, South Korea David Hockney: Etchings, Pace Prints, New York, New York David Hockney: Something New in Painting (and Photography) [and even Printings]... Continued, L.A. Louver, Venice, -

British Figurative Art Since 1950

BRITISH FIGURATIVE ART SINCE 1950 Next week we will look at one of the most famous figurative artists, David Hockney, and this week we will cover eight figurative artists more briefly. Figurative art has long been a feature of British art and the artists most often associated with figurative art since WWII are those of the ‘School of London’. This is a term invented by artist R.B. Kitaj to describe a group of London-based artists who were pursuing forms of figurative painting in the face of avant-garde abstraction in the 1970s. Last term we looked at a few figurative artists who painted between 1900 and 1950 including: • John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), an American artist who worked in Britain and became the leading portrait painter of his generation. • Walter Sickert (1860-1942), a painter’s painter and one of the most influential British artists of the twentieth century. • Gwen John (1876-1939). Gwen John, was an intense and solitary artist who was described by her brother Augustus John as the better artist. • Augustus John (1878-1961) Augustus John was one of the most popular society portrait artists at the beginning of the twentieth century. • Laura Knight (1877-1970) Knight was a painter in the figurative, realist tradition who was among the most successful and popular painters in 1 Britain. In 1929 she was created a Dame, and in 1936 became the first woman elected to the Royal Academy since its foundation in 1768. • William Orpen (1878-1931) an Irish artist who worked mainly in London. William Orpen was a fine draughtsman and a popular, commercially successful, painter of portraits for the well-to-do in Edwardian society. -

Whitechapel Gallery Name an Exhibition

Whitechapel Gallery Name an Exhibition 1901 Modern Pictures by Living Artists: Pre-Raphaelites and Older English Masters – Burne-Jones, Constable, Hogarth, Raeburn, Rubens – Dominic Palfreyman Chinese Life and Art Scottish Artists – Bone, Landseer, Mactaggart, Muirhead, Whistler 1902 Cornish School- Forbes, Stokes Japanese Exhibition Children's Work: Tower Hamlets Schools 1903 Artists in the British Isles at the Beginning of the Century – Fry, Legros, Tonks, Watts Poster Exhibition: British, European, Chinese and Japanese Shipping 1904 Scholars' Work from Board Schools in Bethnal Green, Stepney and Poplar Dutch Art – Hals, de Koninck, Metsu, Rembrandt, van Ruisdael, Amateurs and Arts Students Indian Empire 1905 LCC Children's Work from Board Schools in Bethnal Green, Stepney, Poplar British Art 50 Years Ago – Hunt, Millais, Rossetti, Ruskin, Turner Photography – Chesterton, Pike, Reid, Selfe, Wastell 1906 Georgian England Country in Town Jewish Art and Antiquities 1907 Old Masters: XVII and XVIII Century French and Contemporary British Painting and Sculpture – Boucher, Le Brun, Chardin, Claude, David, Grenze, Poussin Country in Town Animals in Art 1908 Contemporary British Artists: Collection of Copies of Masterpieces – Gainsborough, Holroyd, Latour, Stevens, Teniers Country in Town Muhammaden Art and Life (in Turkey, Persia, Egypt, Morocco and India) 1909 Stepney Children’s Pageant Tuberculosis Flower Paintings and Old Rare Herbals Historical and Pageant 1910 Society of Essex Artists Students Attending London Technical, Art and Evening -

CRAIGIE AITCHISON Is the Painter of Crucifixions and Bedlington Terriers

CRAIGIE AITCHISON Is the painter of crucifixions and Bedlington terriers a visionary or just an eccentric? (The Telegraph Magazine, 2003) Nothing can adequately prepare you for Craigie Aitchison’s house in south London, but if you imagine a cross between Aladdin’s cave and the premises of Steptoe & Son, you will be half way there. The amount of bric-a-brac is heroic. In the drawing-room, with its puce walls, bright blue door and gilded furniture, a larger-than-life china rabbit stares out of the window beside a statuette of Christ; the surfaces are covered with every imaginable trinket, from a brass palm tree to a flock of coloured glass budgerigars perched on the rim of a basket; a sparkly little reindeer sits in one corner, and a painted wooden cow from an Indian temple in another. The alarming news is that these are only half the original contents of the room, the rest having recently been removed to Aitchison’s Italian home near Sienna. ‘Chaos’ and ‘Kitsch’ are two words that spring to mind, but it would be wrong to suppose that Aitchison’s clutter has been acquired in a haphazard or ironic manner. ‘He has got total recall about the things in his house,’ explains his friend Lord Snowdon: ‘you think that they’ve all been thrown down, but every single one has its place.’ Aitchison regards this rum collection of disparate objects as essential to his work, and many of them have appeared – transformed into images of grace and beauty – in his colourful, idiosyncratic paintings. -

SPOTLIGHT on EUAN UGLOW 22 March – 12 April 2003 Buckley Library

SPOTLIGHT ON EUAN UGLOW 22 March – 12 April 2003 Buckley Library Euan Uglow (1932 – 2000) was a painter of national and international distinction. This National Touring Exhibition from the Hayward Gallery comes to Buckley in February before touring extensively around the UK. Spotlight on Euan Uglow brings together six paintings and four drawings from the Arts Council Collection, and offers an opportunity to look again at his work. When he died in August 2000, an obituary writer observed that ‘a light in English painting has gone out’ The works include an early still life, a profile of a girl, a mosque in Turkey and three nudes, including the important painting, The Quarry Pignano, 1979 – 80. Of the four life drawings also shown, Girl Close-To, 1968, is one of the few never intended as a preparatory study, but considered by the artist as a complete work. Uglow had many admirers, including David Sylvester, Paul Smith and Cherie Blair. His extraordinary paintings were long in the making, pursuing the same objective year after year, using traditional methods and a narrow range of subjects – the model in the studio, portraits, still life and landscape. William Coldstream and the Euston Road School, and its search for visual truth, were important influences. However, Uglow’s power lies in the calm and assured way that the motifs hold their place on the canvas and the rich tonal compositions. He gave the same attention to arranging a still life or a model’s pose as he would later give to applying paint on canvas, combining mathematical calculation with careful observation. -

Avigdor Arikha Frank Auerbach R.B. Kitaj Euan Uglow Avigdor Arikha Frank Auerbach R.B

AVIGDOR ARIKHA FRANK AUERBACH R.B. KITAJ EUAN UGLOW AVIGDOR ARIKHA FRANK AUERBACH R.B. KITAJ EUAN UGLOW 11 de mayo - 23 de junio de 2016 ENRIC GRANADOS 68, 08008 BARCELONA T. 93 467 44 54 · F. 93 467 44 51 GALERIAMARLBOROUGH.COM “A LATE QUARTET” ÀLEX SUSANNA Reunir en una misma exposición una selección de obras de estos cuatro pintores no es caprichoso ni aleatorio, Kitaj es un norteamericano trasplantado en Europa en busca de sus orígenes: la Viena de su padre adoptivo, pero pero tampoco inevitable. Y, en cambio, el cóctel es explosivo y tremendamente estimulante. De los cuatro sólo todavía más la de Aby Warburg, figura clave para desentrañar la sintaxis de su imaginario. En 1962 se instala en uno les sobrevive, pero todos pertenecen a la misma generación y, si bien nacidos en países distintos, tienen Londres y en 1976 impulsa la exposición colectiva “The Human Clay”, en la que reivindica una nueva figuración trayectorias en cierto modo convergentes: Avigdor Arikha (Rădăuţi, Rumanía, 1929-2010), Frank Auerbach –la de Bacon, Freud, Auerbach, Kossoff y Hockney, entre otros– y se refiere por primera vez a la Escuela de (Berlín, 1931), R.B. Kitaj (Cleveland, Ohio, 1932-2007) y Euan Uglow (Londres, 1932-2000). Londres. Como artista, su propósito es bien claro: “Me gustaría intentar no sólo volver a hacer Cézanne y Dégas después del surrealismo, si no después de Auschwitz y del Gulag”. Su obra parte, pues, de un feroz diálogo Presentarlos juntos es toda una declaración de intenciones y una provocación, sobre todo en estos tiempos en tanto con sus predecesores –la ansiedad de las influencias– como con la historia más reciente y traumática: bajo que la práctica de la pintura cada día parece más negligida a ojos de los que se creen y proclaman portavoces una piel de una erizada vivacidad plástica, cada obra se nos aparece como un palimpsesto de múltiples capas, de la más apremiante contemporaneidad. -

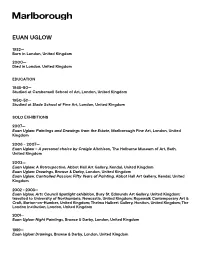

Uglow, Euan CV 08 08 19

Marlborough EUAN UGLOW 1932— Born in London, United Kingdom 2000— Died in London, United Kingdom EDUCATION 1948-50— Studied at Camberwell School of Art, London, United Kingdom 1950-52— Studied at Slade School of Fine Art, London, United Kingdom SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2007— Euan Uglow: Paintings and Drawings from the Estate, Marlborough Fine Art, London, United Kingdom 2006 - 2007— Euan Uglow – A personal choice by Craigie Aitchison, The Holburne Museum of Art, Bath, United Kingdom 2003— Euan Uglow: A Retrospective, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, United Kingdom Euan Uglow: Drawings, Browse & Darby, London, United Kingdom Euan Uglow, Controlled Passion: Fifty Years of Painting, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, United Kingdom 2002 - 2003— Euan Uglow, Arts Council Spotlight exhibition, Bury St. Edmunds Art Gallery, United Kingdom: travelled to University of Northumbria, Newcastle, United Kingdom; Ropewalk Contemporary Art & Craft, Barton-on-Humber, United Kingdom; Thelma Hulbert Gallery, Honiton, United Kingdom; The London Institution, London, United Kingdom 2001— Euan Uglow: Night Paintings, Browse & Darby, London, United Kingdom 1999— Euan Uglow: Drawings, Browse & Darby, London, United Kingdom Marlborough 1997— Euan Uglow, Browse & Darby, London, United Kingdom 1993— Euan Uglow, Salander O'Reilly Gallery, New York, New York, United States 1991— Euan Uglow: Ideas, 1952-1991, Browse & Darby, London, United Kingdom 1989— Euan Uglow: Nudes, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, United Kingdom Euan Uglow: Drawings, Browse & Darby, London, United Kingdom -

Straw Poll FINAL Copyless Pt Views

Straw poll: Painting is fluid but is it porous? Liz Rideal … the inventor of painting, according to the poets, was Narcissus… What is painting but the act of embracing by means of art the surface of the pool?1 Alberti, De Pictura, 1435 Thoughts towards writing this paper address my concerns about a society that appears increasingly to be predicated on issues surrounding accountabil- ity. I was conscious too, of wanting to investigate perceptions of what has now become acceptable vocabulary, that of the newspeak of 'art practice' and 'art research'. The discussion divides into four unequal parts. I introduce attitudes towards art and making art as expressed in quotations taken from artists’ writings. An historical overview of the discipline of Painting within the Slade School of Fine Art, and where we stand now, as we paint ‘on our island’ embedded within University College London’s Faculty of Arts and Humanities. I report the results of a discreet research project: a straw poll of colleagues in undergraduate painting, stating their thoughts about the teaching of painting. Finally, conclusions drawn from the jigsaw of information. [For the conference, this paper will be delivered against a projected back- drop featuring a selection of roughly chronological images relating to the history and people connected to the Slade over the past 150 years.] The texts written by artists have been selected to reveal the position of art as an un-exact science that requires exacting discipline, dedication and an open mind in order to create art works. Art that can communicates ideas, emotions and instincts in a way that reflects an aesthetic balance of intellect and cre- ativity.